Many people think that “bad” posture is the main cause of most back and neck pain. They think that having a “good posture,” like a neutral or straight back, means that they can decrease or prevent back pain.

But decades of scientific research do not support this idea, yet many companies and health professionals continue to push such ideas.

So it’s not a surprise if you Google “posture” and see tons of ads for posture correctors, corrective exercise, or chiropractic adjustments on your screen.

The obsession with maintaining a “perfect posture” isn’t new. Some historical evidence indicates that some of the roots came from the European military in the Early Modern Period that eventually permeated throughout the world, including Maoist China.

However, you can also see that tall, straight posture in ancient art, such as the terracotta warriors in China and ancient Egyptian paintings and sculptures.

There are some cultural factors that influence our perception of what an ideal or good posture looks like, but that doesn’t mean someone with such posture doesn’t have back pain. You can have pain whether you have “good” or “bad” posture.

So how do you make sense of what you see and hear online about posture and pain? Well, this series highlights some of the common types of posture and what decades of scientific evidence say about it.

Types of posture

There are at least four types of posture that focus on the upper body and the pelvis:

- Upper cross syndrome

- Lower cross syndrome

- Forward head or “text neck”

- Scoliosis

Each of these postures can be divided into more specific ones, including:

- Kyphosis

- Rounded shoulders

- Anterior pelvic tilt

- Posterior pelvic tilt

There are three other types of postures that involve the lower body:

- Valgus knees

- Varus knees

- Leg length discrepancy

You can be born with some of these postures, like scoliosis, or you could get an injury or a disease that causes you to have one. But for most people, it’s likely that your daily habits (e.g. sitting posture), physical activity (e.g. running, weightlifting), and mental health can contribute to why you have a certain posture.

Upper cross syndrome

While upper cross syndrome is common among those who work at a desk job, the posture itself may not be the primary cause of back and neck pain. Taking more frequent breaks and move your body can help alleviate the symtpoms. (Photo: Nick Ng)

Upper cross syndrome is where your shoulders are hunched forward and your neck sticks out like Shaggy in the Scooby-Doo cartoons. This often exaggerates the curvature of the upper spine.

The idea is that “tight” or “shortened” muscles in the chest and upper trapezius and “weak” or “lengthened” muscles in the shoulder stabilizers, neck extensors, and other neck muscles are the cause of this posture.

Upper cross syndrome (and lower cross syndrome) was first proposed and popularized by Dr. Vladimir Janda (1928-2002) in the 1970s.

Unfortunately, his work was never validated or reviewed critically—as most scientific research should be. Yet for decades, many clinicians and fitness professionals took the crossed syndromes as gospel and revolved their treatments, exercise programs, and continuing education around them.

“[These] crossed-syndrome-type things make no sense whatsoever but are not going away any time soon. People will be talking about this brilliant insight for another 50-odd years.

“I wonder if Janda would [facepalm] if he heard how people were unable to move beyond this idea and had more fidelity to this particular product/idea than to the process he advocated.” ~ Dr. Jason Silvernail on SomaSimple, 2017

Forward head posture

A tourist checks his phone with an extreme example of a forward head posture—or “text neck”—near the White House in Washington D.C. in November 2016. (Photo: Nick Ng)

The forward head posture, or “text neck,” is often blamed as a major cause of neck and shoulder pain.

You may have seen some websites or posters in a physical therapist’s office that show the amount of extra weight (10 to 30 pounds) your neck carries if you have forward head posture.

But that doesn’t really mean anything.

Research in the past 40 years on neck posture shows some correlations between a forward head posture and neck pain, but there’s no strong evidence that supports such posture causes pain.

In fact, two recent research fails to find a strong relationship between forward head posture and neck pain. In a 2018 meta-analysis, researchers in China reviewed 21 studies—with a total of more than 15,000 subjects—found no significant differences in posture between those with pain and those without pain.

Men in the sample showed higher neck curvature angle than women, and age did not correlate much with the angle either.

A year later, another study from Cairo, Egypt, reviewed 15 cross-sectional studies that compared the necks of people with and without pain.

Like the Chinese study, the research team found “no statistically significant difference” between both groups.

What this means is that we can’t just assume that such posture causes neck pain. And what if it was the neck pain that causes the forward head posture— is it an adaptation or response to pain?

Kyphosis

Kyphosis is the exaggeration of the upper spine, which sometimes comes with forward head posture. (Photo: Nick Ng)

Kyphosis falls under the umbrella of upper cross syndrome. It exists in nearly everyone’s upper spine in various degrees, but too much outward curve—sometimes called a “hunchback” or “dowager’s hump”—can reduce range of motion and increase the risk of some joint disorders and diseases.

But research has shown that kyphosis is more than just about your structure.

A 2021 systematic review of 34 studies of more than 7,600 older, healthy adults found that having increased kyphosis is part of normal aging. It doesn’t mean that such posture can inhibit an independent life; perhaps it’s just not as bad as some people claim it to be.

Even so, having too much kyphosis (hyperkyphosis) may increase the risk of getting a vertebral fracture among those with osteoporosis and reduce the shoulder’s range of motion. In such cases, exercise and/or surgical treatments may be needed to reduce the curve or at least prevent you from rounding your back more.

Treatments for kyphosis are mixed because there’s no one-size-fits-all method for all cases.

For example, there’s some evidence that a back brace can reduce the kyphotic curve among those with Scheuermann’s kyphosis, which is a congenital condition.

But for hyperkyphosis caused by aging, there’s little good evidence that bracing would work for that. A 2021 systematic review found two qualified bracing studies that showed it has a “large effect” in reducing hyperkyphosis, but the evidence is weak because of their “imprecision” and publication bias.

Two additional studies were included in their meta-analysis, but there was “insufficient data” to calculate the effect size, which is important in determining how likely the results were based on chance.

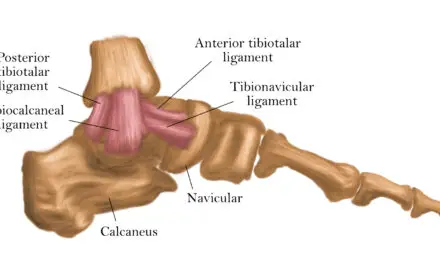

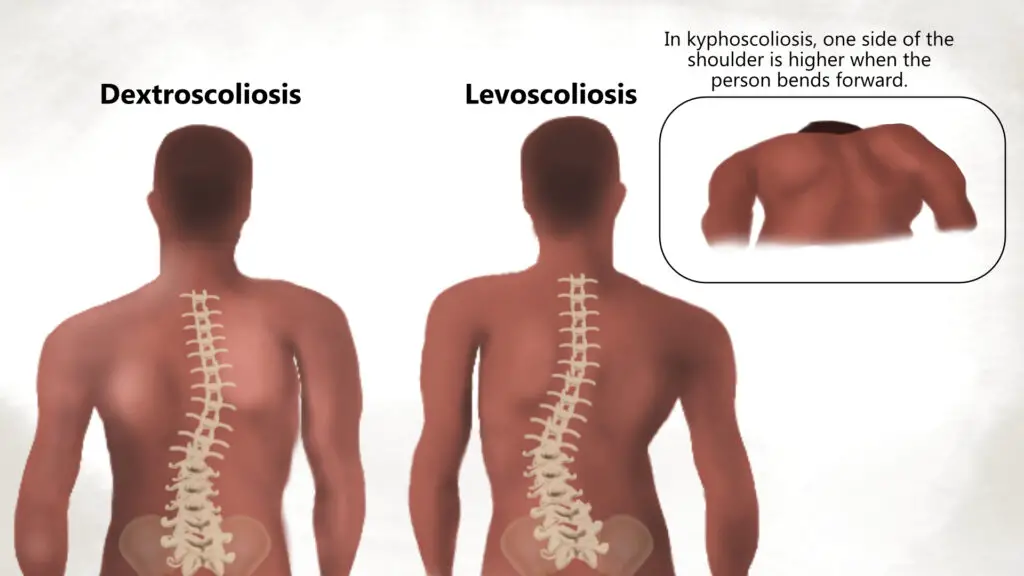

Kyphoscoliosis

Kyphoscoliosis has characteristics of both kyphosis and scoliosis. It may even feature two types of scoliosis where the curve starts either at the lower or upper thoracic spine. (Illustration by Nick Ng.)

Kyphoscoliosis is an extreme form of spine deformity that has features and symptoms of both kyphosis and scoliosis. Because it’s not as common as other types of postures, there isn’t a lot of scientific evidence to guide treatment. However, based what is known about kyphosis and scoliosis, early intervention—especially at a young age—to minimize the progression and severeity include:

- bracing

- surgery

- physical therapy

There are cases where a person with kyphoscoliosis might not have pain or other symptoms. Thus, a regular check-up with a physician may be necessary.

Rounded shoulders

Rounded shoulders is another feature that tags along with upper cross syndrome. It’s where your shoulder blades are tilted forward that gives the slouching posture.

This is usually coupled with tight chest muscles and a forward head with the arms and hands internally rotated, similar to a gorilla.

Like other types of posture, the cause-and-effect relationship isn’t always directly related to back pain or neck pain. In fact, psychological health can affect how your posture is.

Some research points out that people with severe chronic depression often adopt a slouching posture. And so, posture could be a useful indicator to detect someone’s behavior changes and quality of life.

Lower cross syndrome

Cross syndromes as described by Dr. Vladimir Janda were never validated or critically reviewed. (Image: Nick Ng)

Lower cross syndrome is another example of “Janda’s postural syndromes” that follows the same logic as upper cross syndrome.

Many images tend to show a sideway view of someone with an “X” drawn in the middle of the abdominal and pelvic region to show which muscles are “tight” and “weak.” They can have an excessive lordotic curve or a flatter lower back.

The aim is to identify these areas to bring the pelvis and spine as close to “neutral” position as possible.

But this can be problematic because—like upper cross syndrome—there’s no reliable evidence that lower cross syndrome causes back or hip pain.

Research finds that posture assessments are unreliable because people have different bony landmarks and shapes in their pelvis that may give clinicians the wrong diagnosis for your back or hip pain.

Anterior pelvic tilt

The anterior tilt is where the pelvis is rotated forward, which often increases the lordotic curve. But this posture doesn’t mean it’s a cause of back pain, according to most research. (Photo: Nick Ng)

In the anterior pelvic tilt, the pelvis is rotated forward, causing an increase of the lumbar spine curvature. This is like holding a basin in your hands and tilting it forward to pour water. This position tilts the gluteal muscles upward, exaggerating its round appearance for some people.

Research has shown that people with different pelvic tilts can have back pain or not. A large 2002 study of 600 people in Tehran, Iran, found that structural factors, such as pelvic tilt, the degree of lumbar lordosis, and length of abdominal and psoas muscles, “are not associated with the occurrence of [low back pain].”

People with or without low back pain had variations of pelvic tilts that make identifying who has back pain or not challenging for clinicians. Even a systematic review of 43 studies fails to find pelvic tilts as a reliable predictor and indicator of people having low back pain.

However, the researchers do find that those with low back pain tend to walk and bend forward slower than those without pain, and they often have a harder time “repositioning” to neutral position after they perform a trunk flexion and extension.

Posterior pelvic tilt

The posterior pelvic tilt is where the pelvis is rotated back in the sagittal plane, causing a reduction in the curvature of the lumbar spine and buttocks. Sometimes the pelvic tilt exaggerates the upper spine curvature, making the person appear more hunchback.

Like the anterior pelvic tilt, there’s no reliable evidence that shows the posterior tilt is a cause of back pain.

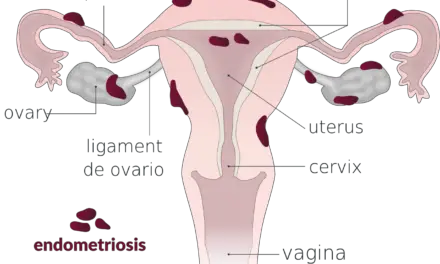

Scoliosis

Most scoliosis, particularly mild ones, are often asyptomatic. (Photo: Nick Ng)

Scoliosis is where your spine curves sideways, sometimes forming a rough S-shape. It may be a single or double curve, and it can even occur with kyphosis and lordosis. While many people blame scoliosis for back and hip pain, scientific evidence finds that it’s more than just the spinal posture alone.

In fact, one huge South Korean study of more than 1,300 older adults found that the degree of the curvature of scoliosis isn’t correlated with the pain severity.

Among teens, a Canadian study of 124 people with idiopathic scoliosis found that those who think their pain will get worse are more likely to have back pain than those who don’t have such thinking.

And so, scoliotic back pain could be affected by stigma, fear, and and various psychosocial factors that influence their pain experience.

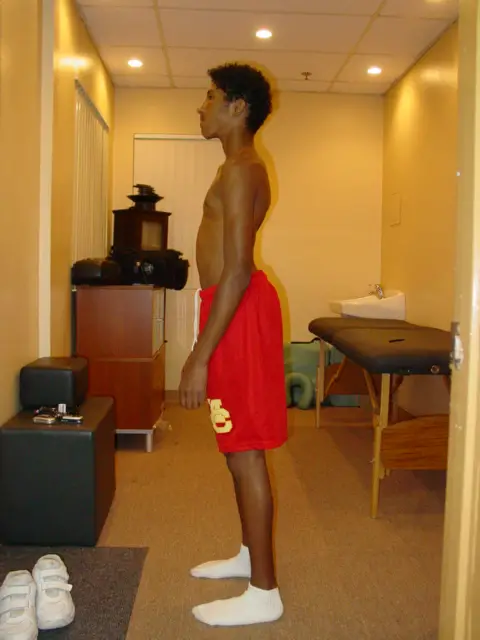

Q-angle

A Q-angle shows the degree of movement of the knee in relation to the hip as the person performs a lunge. (Photo: Penny Goldberg)

The Q angle is the angle between the middle of your quadriceps muscle and the patellar tendon. This is like the “posture of the knees.” Many clinicians thought it’s associated with the “knock-knee” or valgus position, but this is not supported by the research.

One U.S. study found that the ratio of the pelvis’ width to the femur’s length, not the Q-angle, to be a predictor of getting valgus during movement.

People with Q-angles greater than 17 degrees didn’t have a greater knee valgus angle during a single-leg squat than those with Q-angles less than 8 degrees.

This suggests that variations in bony anatomy alone are not that important for knee pain. Like most types of pain, other factors—such as lifestyle, smoking and dietary habits, mental and social health, gender, and sleep quality—should also be considered when finding out why you have knee pain.

Varus knees

Varus knees, or “bow-legged,” is where your kneecaps point away from your body’s midline when you stand. The stereotypical cowboy stance is an example of varus.

Knee varus can cause the pelvis to roll backwards into a posterior pelvic tilt, which flattens your low back curve.

Some evidence finds that having varus knees may increase the likelihood of knee pain, according to a 2022 systematic review of 40 studies on people with osteoarthritis. However, the researchers noted that long-term studies are needed to determine the cause, which means we shouldn’t jump to conclusions about varus knees can cause knee pain.

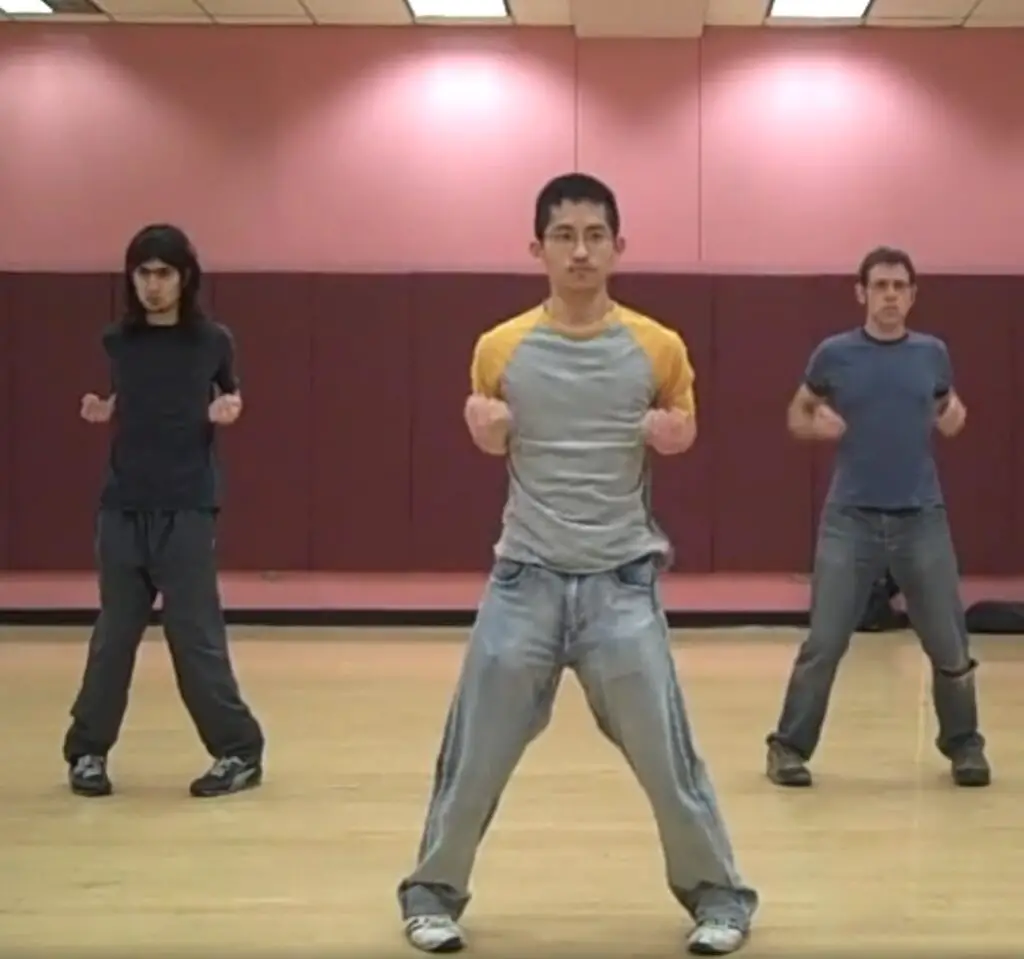

Valgus knees

Wing chun stance “Yee Jee Kim Yueng Ma” with valgus knees. (Screenshot by Nick Ng.)

Valgus knees, “knock-knees,” is where your kneecaps point toward each other when your stand, such as in the wing chun kung fu stance.

If there’s to much load on the outside of your knees, there’s an increased likelihood of certain knee problems, like as arthritis. Too much varus or valgus may be an independent risk factor for the development of knee arthritis.

Knee valgus can cause problems with patella tracking, where the quadriceps pull the patella outward relative to the trochlear groove of the kneecap and patellar tendon attachment. Knee valgus and patellar tracking issues have often been associated with pain in or around the joint between the kneecap and the knee.

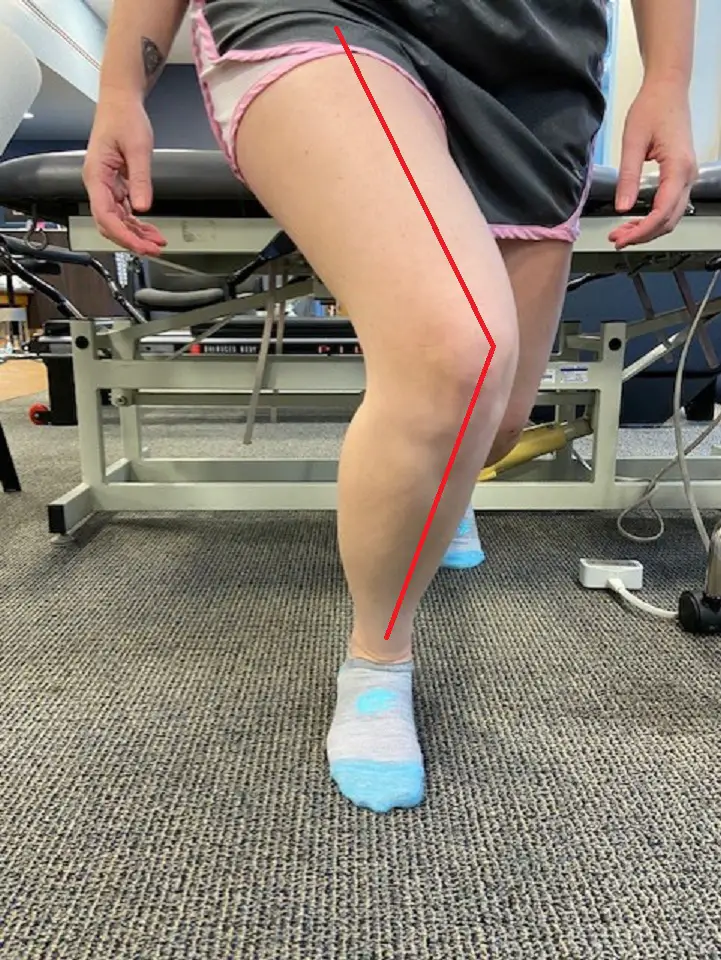

Leg length discrepancy

Photo: Penny Goldberg

Leg length discrepancy is where one of your legs is longer than the other. This can be caused by actual differences in lengths of your leg bones or your pelvis is tilted sideways.

Do you need to fix your leg length? In most cases, probably not. Current research finds that a difference of 10 millimeters often don’t cause any problems and is a normal variation of human anatomy, so you probably don’t need to worry.

But discrepancies more than 20 millimeters may be some kind of treatment, such as having custommized orthotics or physical therapy. Common problems that come with such leg length discrepancy is include difficulty in walking, uneven loading of the shorter limb that can cause excess wear and tear of the knee, and increased risk of scoliosis in children.

So do I need to fix my posture?

If you have read this far, then you should get a general idea that the current evidence finds a weak relationship between posture and pain. And like there’s no such thing as a perfect body, there’s no such thing as a perfect posture.

While some specific conditions, like severe kyphoscoliois and pelvic tilts, can limit range of motion or increase the risk of joint diseases, you shouldn’t worry too much about it.

“People need to know the back loves movement, is designed to bend and lift, and so it should not be wrapped in cotton wool,” wrote physiotherapist Mary O’Keefe, who is a pain researcher at the University of Australia.

So instead of trying to fix your posture, here are some alternatives according to science:

- Exercise more regularly: Whether it’s lifting weights at the gym or hiking in the trails, exercise can be a natural painkiller as long as it doesn’t increase your pain. If you don’t like yoga or Pelaton, try something else. The type of exercise isn’t that important; the act of exercising is. Even playing with your kids or dog is exercise. Or playing a video game like Beat Saber. So find something you like to do and stick with it.

- Take more breaks and move: If you have a desk job, get up and move around for a few minutes. Stretch if you want to. (Those who drive for a living (e.g. trucking, Uber), it may be more challenging to find the time.)

- Improve your sleep: A good night’s sleep could be something you can do to reduce your nagging back pain. Research has shown a strong association between a lack of sleep and increase risk of having chronic pain.

- Educate yourself about pain: There are plenty of reliable resources that you can explore about pain, which can help you be better informed to find the best way to manage your pain and avoid treatments and products that don’t really work well for specific pains. These include:

- Your local healthcare provider: some hopsitals, such as Kaiser Permanente, offer pain education programs that are often up-to-date in the science and application of the research.

- PainScience.com: this site offers library of topics that critically examine different types of treatments for pain, including massage therapy, chiropractic, energy healing, and exercise.

- Retrain Pain Foundation: founded by three physical therapists from New York City, this organization offers a quick and easy guidance that answers common questions about pain.

- The Pain Management Workbook: authored by pain psychologist Rachel Zoffness, this self-guided workbook helps you navigate your own journey to manage your chronic pain.

Remember that pain is a complex experience that comes from different sources, including our mind, environment, social life, and the interactions of our hormones, immune cells, and the nervous system.

And posture is just one tiny factor that contributes to our pain experience.

So before you accept an offer or buy a product that promises to “fix” your posture, consider the evidence before you make your final decision. And sometimes, all you might need is to just change your body positions if you were to sit or stand for a long time.

A native of San Diego for nearly 40 years, Nick Ng is an editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine, an online publication for manual therapists and the public who want to explore the science behind touch, pain, and exercise, and how to apply that in their hands-on practice or daily lives.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a B.A. in Graphic Communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014.

When he is not writing or reading, you would likely find him weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, or exploring new areas to walk and eat around Southern California.