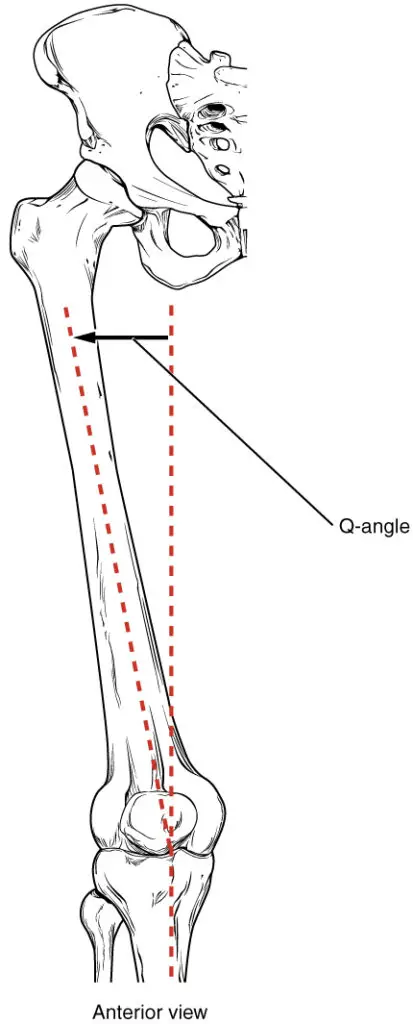

The Q angle—or quadriceps angle—is the distance between two imaginary lines: one line is drawn from the ASIS of the pelvis to the middle of the patella, and then a second line is drawn from the patella’s center to the tibial tubercle.

This angle represents the pull of the quadriceps and can play a major role in knee mechanics. It may also be useful for predicting the severity of hip labrum tears. It can potentially affect your posture and the structures of your hip and knee joints, which should be considered when pain is at either location.

The Q-angle is where two imaginary lines cross, drawn from the midpoint of the patella. One line connects to the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) of the pelvis and the other to the tibial tubercle. (Image by OpenStax College, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported.)

How to measure the Q angle

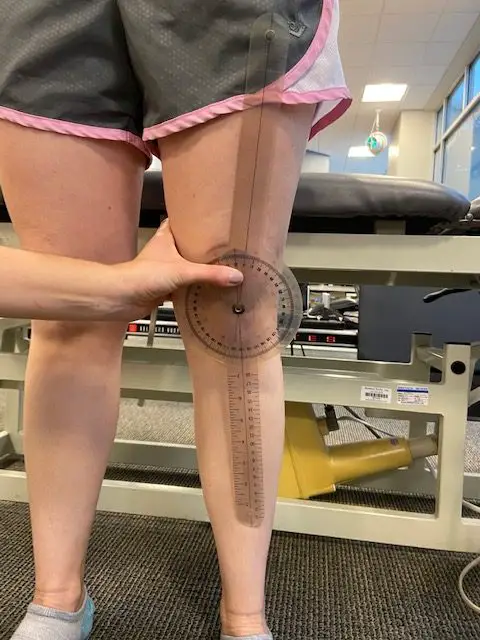

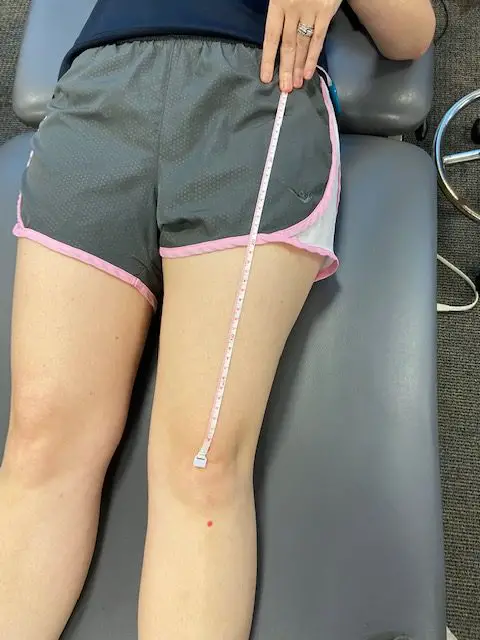

A goniometer is used to measure the Q angle while the patient is standing or sitting. (Photo by Penny Goldberg.)

To measure the Q angle, a standard goniometer is used. Then:

- Stand next to the person lying face up on a treatment table.

- Identify the ASIS (anterior superior iliac spine), the middle of the patella, and the tibial tuberosity.

- Make sure the foot of the leg that’s being measured is in a “neutral” position (not rotated too laterally or medially).

- Draw an imaginary line with a string or in your head from the ASIS to the middle of the patella. Then draw another line from there to the tibial tubercle of the upper tibia.

- Measure the angle formed by the crossing of these two lines. Now you have the Q angle.

Use a string to initially find the ASIS of the hip and the middle of the patella. (Photo by Penny Goldberg)

You can also measure with the person in a standing or sitting position, but the gravity and tension in the muscles and joints may affect the measurement.

How reliable is the Q angle measurement?

Research has shown that the Q angle measurement has excellent consistency between and among testers, which means that this is an easy and accurate test that can be used by novices and experts.

There’s also not much difference in how it’s measured from a standing or sitting position. And so, it’s likely not clinically or practically relevant. The researchers also found that weight and leg dominance did not affect the measurement accuracy much. It seems that measuring in supine and standing positions is the most complete method.

So when measuring the Q angle, consider these factors that influence the angle size:

- gender

- height and weight

- size of the lower leg and patella

- rotation of the femur, patella, and tibia

What is a “normal” Q angle?

The normal Q angle falls between 14 and 16 degrees for men and 16 and 18 degrees for women. However, it seems to be somewhat arbitrary.

For example, researchers measured the Q angles of 50 men and 50 women from a standing position and found the average Q angle was nearly 16 degrees in women and 11 degrees in men.

Also, when measured in a standing position, different researchers found the Q angle’s average to be 9 degrees in men and 13.5 degrees in women. These inconsistent findings may suggest a wider range of Q angles than has been previously reported.

The Q angle is made up of two imaginary lines that begins at the middle of the kneecap. One goes from the ASIS of the pelvis and the other to the tibial tubercle. High Q angles due to knee valgus is often blamed for knee pain, but research finds that it’s not always the case. (Photo by Penny Goldberg)

Does the Q angle affect knee pain?

Some people think that a larger Q angle increases the likelihood of getting knee pain from valgus knees, but research finds that it’s not as likely as you think. For example, researchers from the University of Buffalo in New York found that people with Q angles greater than 17 degrees did not have a greater knee valgus angle during a single-leg squat than those with Q angles less than 8 degrees.

This suggests that variations in bony anatomy alone are not necessarily cause for concern when it comes to knee pain.

Also, a study of 22 women with patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS) was unable to find any correlation between the Q angle and pain intensity, functional capacity, or dynamic knee valgus.

Despite conflicting evidence on its role, many clinicians still blame the Q angle for knee and lower extremity injuries. Q angles outside of the normal reported ranges (greater than 15 degrees in men, greater than 20 degrees in women) are considered an anatomical risk factor for development of overuse injuries in the knee.

For those with knee pain with large Q angles, exercise can help. A study of 34 elite athletes, who performed a supervised, weight-bearing exercise program over an eight-week period, found that both dynamic Q angles (measured with digital images) and pain decreased significantly at the end of the program.

This suggests that closed kinetic chain exercises—that is, exercises done with your feet in contact with the floor, such as squats and lunges, rather than leg raises and clam shells—should be used.

Patellar tracking and Q angle

Knee mechanics are often described using a ‘train on the tracks’ analogy, but it would seem we may have been blaming the train when the track was the problem (also known as patellar tracking).

The relationship of the patella to the quadriceps tendon is such that the femur can move independently. In fact, some researchers found that femoral internal rotation, not malalignment of the patella, is the primary contributor to lateral tilt of the patella, which may lead to knee pain and pathologies.

Despite their findings, many manual therapists still believe that people with larger Q angles are more likely to have knee pain compared to those with small angles. One reason why they hang on to this idea is that it’s been demonstrated time and again that forces at the knee—and therefore, potential for injury—are higher when the Q angle is larger.

Does the Q angle affect hip pain?

There’s no direct link between the Q angle and hip injuries, but there’s evidence that there’s a link between femoral version and the Q angle and femoral version and femoroacetabular impingement.

For example, a study of 204 painful hips found that femoral anteversion (head of femur turning inward) greater than 15 degrees was associated with larger labral tears. Patients with less than 5 degrees of retroversion (head of femur turning outward) had the smallest tears. Also, those with more than 15 degrees of anteversion were twice as likely to have anterior tears.

Those with more anteversion tended to have larger labral tears and needed surgical release of the psoas muscle to decrease symptoms and improve function.

In actual hip pain management, these patients may present with more complex surgical considerations. Rehab professionals should be clear on the details and extent of the surgical procedures.

Genu valgum

Genu valgum, often referred to as “knock-kneed” or valgus knee, is where your knees are rotated inward to make your patella point toward each other. Research finds that there’s some relationship between the Q angle and genu valgum.

For example, a study of 218 men and women examined the relationships between alignment of the lower extremity and Q angle and found that the tibiofemoral angle and the femoral anteversion were strongly associated with greater Q angles in men and women.

This work revealed that changes in the tibiofemoral angle have a greater impact on the Q angle than femoral anteversion. Every one degree change in anteversion predicted a 0.18 degree change of the Q angle of males and females.

However, since the Q angle is mainly a frontal plane measurement, it may not be sufficient for examining its role in lower extremity injuries. And so, clinicians must take muscle strength and range of motion into account when examining a patient for existing or potential injury or pathology.

Currently, clinicians cannot accurately measure static posture and dynamic knee function in both the frontal and transverse planes, which leaves most injury risk assessments to be only hypothetical.

Genu recurvatum

Genu recurvatum is hyperextension of the knee, which means the knee gets so straight to the point where it may even appear to bend in the opposite direction. Currently there’s no clear relationship between the Q angle and genu recuvatum.

For example, a study of 130 female athletes who were evaluated for several lower-body alignment conditions was unable to establish a relationship between genu recurvatum and the Q angle.

The relationship of the lower extremity alignment and knee injuries has been a major focus of research for quite some time, but the role these variables play in general knee function and risk of injury remains controversial. Along with the patient’s history and other clinical findings, the position of the bones of the lower body should be considered when looking for causes of knee pain.

Can you fix the Q angle?

Whether the Q angle can or even needs to be fixed is dependent on each person’s condition. A large Q angle without pain or symptoms is not a cause for concern. In fact, trying to change something that isn’t currently a problem can lead to problems that would have otherwise been avoided.

In those with knee pain and symptoms, rather than trying to change Q angle, clinicians should focus on restoring muscle function and control, strength, and joint range of motion.

Once these factors have been addressed, focus on proper form with exercise and activities of daily living. The Q angle may change throughout the process, but physical change is not often a treatment goal.

Q angle and massage therapy

Although massage therapists do not regularly measure Q angles, an understanding of how this condition changes the angle of pull of the muscles that cross the hip and knee joint is critical.

A greater Q angle will cause the kneecap to sit more toward the outside of the leg which allows the soft tissues—specifically the vastus lateralis and the lateral retinaculum—to get tight.

To address such tissue changes, massage therapists should focus on reducing lateral tension at the knee through muscle bending of the quadriceps.

Different massage techniques to the front and back of the leg can also be used, and the technique used should reflect on the patient’s preference. The patient should be positioned in supine to allow easy transitions between work at the anterior hip, lateral thigh, and quadriceps muscle belly. Bending the knee will also allow some hamstring work, but a transition to prone may be necessary for deeper massage strokes.

If the patient cannot lie on their back for a long time, they can alternate between side-lying with a pillow between the knees so the therapist can work on the lateral knee and supine for anterior hip and quadriceps work.

Although the relationships are often difficult to define, it’s evident that knee pain and other conditions are rarely linked to a single cause. Being aware of the relationship between the Q angle and hip and knee functions can assist in exercise planning, guide lifestyle changes, and direct massage therapy treatment.

Penny Goldberg, DPT, ATC

Penny Goldberg, DPT, ATC earned her doctorate in Physical Therapy from the University of Saint Augustine and completed a credentialed sports residency at the University of Florida. She is a Board Certified Clinical Specialist in Sports Physical Therapy.

Penny holds a B.S. in Kinesiology and a M.A. in Physical Education from San Diego State University. She has served as an Athletic Trainer at USD, CSUN, and Butler University.

She has presented on Kinesiophobia and differential diagnosis in complicated cases. Penny has published on returning to sports after ACL reconstruction and fear of movement and re-injury.

Outside of the clinic, Penny enjoys traveling, good cooking with great wine, concerts, working out and playing with her dogs.