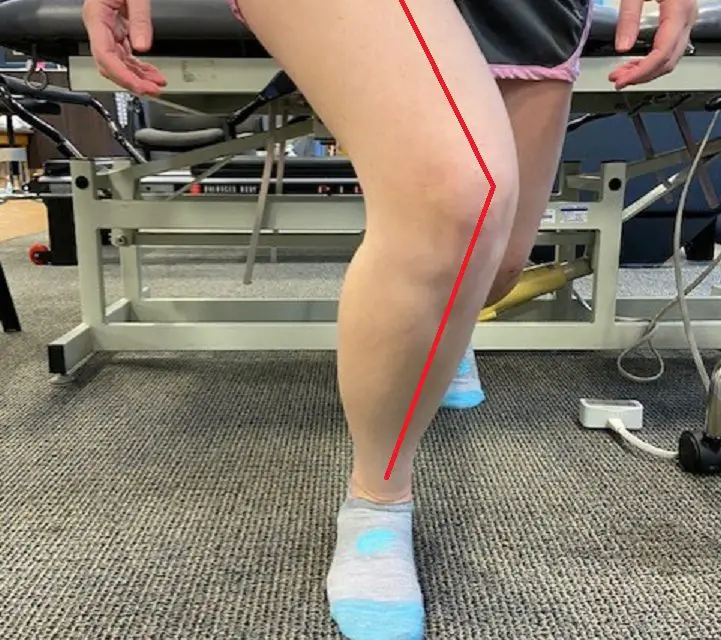

Valgus knee, also known as ‘knock-knees’ or genu valgum, is where your knees angle in towards the midline of your body. This can lead to foot pronation on the affected side and is sometimes associated with increased lordosis, which can cause a forward tilt of the pelvis.

Knee valgus is often normal during early childhood. However, there are circumstances where having it may be an underlying problem that may require treatment.

The patella, or kneecap, functions as a fulcrum to increase the force of the quadriceps muscles. It sits in the trochlea, a groove between the two rounded ends of the femur. The tendon of the quadriceps encases the patella and continues downward to attach at the top of the shin.

Knee valgus can cause problems with tracking of the patella, as the quadriceps pull the patella outward relative to the trochlear groove and patellar tendon attachment. Valgus and patellar tracking issues have often been associated with pain in or around the joint between the kneecap and the knee. It can also be a significant factor in the developing patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS), a painful condition around the joint between the patella and trochlea. There’s strong evidence that knee arthritis is associated with both the shape of the trochlea and the alignment of the knee when viewed from the front.

For example, Japanese researchers examining a group of 34 women with varus or valgus alignment found that subjects with valgus engaged their quadriceps more strongly when landing from a jump. In landing, subjects with valgus were not able to transfer force through to their hip joints as effectively as those with a varus knee alignment. This could have relevance for those working with athletes, especially those who regularly engage in explosive and high-speed jumps and landings.

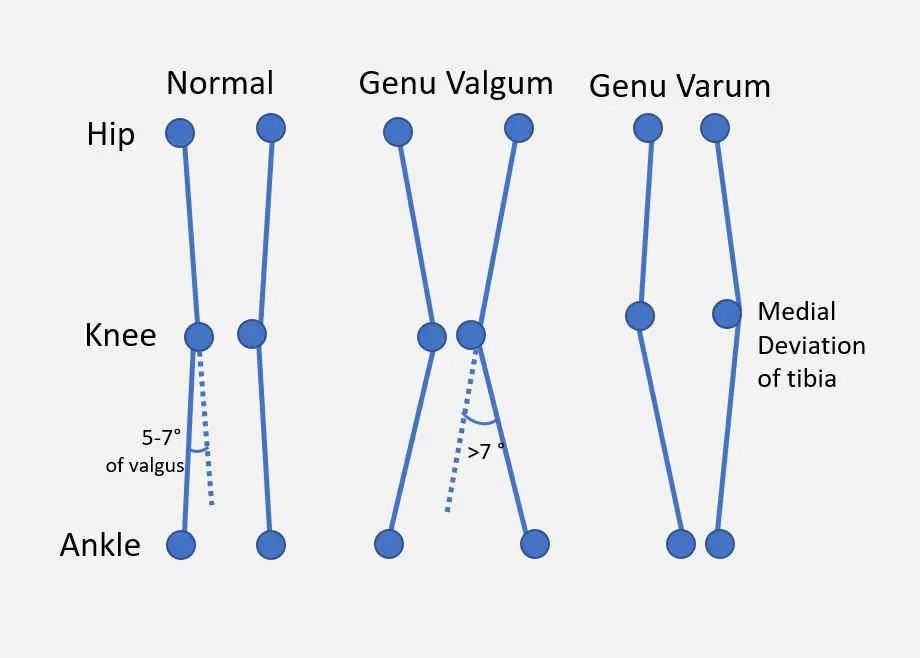

Valgus vs. varus knee

A simplified comparison of “normal,” valgus, and varus knees. (Image by Dr. Vijaya Chandar, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International.)

In a valgus knee, the knees angle in towards one another and likely touch in a standing position. This causes the lower legs to splay out with the feet spaced apart. It is also sometimes referred to as knee adduction where the foot and lower leg moving closer to the midline than the knee. Picture a classic cowboy stance, and that’s varus.

Knee valgus is also sometimes referred to as knee abduction. This describes a movement of the lower leg and foot away from the midline.

In a varus knee, or genu varum, the opposite is seen. The knees curve away from one another, even with the ankles touching while standing. This is also called ‘bow-legged’ (referring to the curve of an archer’s bow) or ‘bandy-legged’. It can cause the pelvis to roll backwards into a posterior pelvic tilt with the flattening of the low back curvature.

Symptoms of valgus knee

Sometimes having valgus knees don’t give you any pain or movement problems, but sometimes it could. Common symptoms include:

- degenerative tissues on the lateral side of the knees

- patellar tracking or alignment

- pain in the front of the knee (patellofemoral pain syndrome)

- difficulty in walking or running

- stiff and sore knee or hip joints

- feet don’t touch when you stand with your knee together

- progressive knee arthritis

Valgus exercises

Exercise could train your body and brain to reduce your knee valgus. These are meant for those who do not have pain or severe movement control. If you have a little bit of valgus when you squat or land from a jump, these might help.

Single-leg lunge with elastic band

By wrapping an elastic band around your thigh close to your kneecap, this exercise forces you to push your knee away from your body’s midline when you lunge.

- Wrap an elastic band around your right thigh and bring it close to your kneecap. Secure the band to a sturdy object like a heavy table or wall hook.

- Get into a lunge position by standing with your right foot in front of you and your left foot behind you. They should be about 2 to 3 feet apart, depending on your height and leg length. Your right knee and foot should be pointing forward.

- Lower your body toward the ground until your left knee almost touches the ground. Keep your torso upright.

- Exhale as you stand back up. Repeat for 8 to 10 reps for 2 to 3 sets. Do the same thing for the opposite side.

Goblet squat with elastic band

This exercise follows the same idea as the lunge by preventing your knee from collapsing inward.

- Wrap an elastic band around both thighs near the top of your kneecaps.

- Hold a 10- to 20-pound dumbbell or kettlebell in front of you near your chest.

- Stand with your feet about hip-width apart with your toes pointing slight away from each other.

- Inhale as you squat down as low as you can or at least until your buttocks move just below your knee level.

- Exhale as you stand back up. Repeat for 8 to 10 reps for 2 to 3 sets.

Caveat: In some activities, knee valgus is a normal part of movement. These include dance (e.g. hip-hop, mambo) and martial arts (e.g. wing chun).

Valgus knee causes

There are several factors that can lead to having valgus knees:

- Being female: having a wider pelvis (than me) may increase the risk;

- Hip muscle weakness: while this is debatable, there’s some evidence that having a certain amount of hip strength can decrease the risk;

- Q-angle: a wider angle between the quadriceps and the patellar tendon may increase the risk. However, not everyone with a large Q-angle have valgus knees;

- Paralysis or cerebral palsy

- Bone pathologies, such as rickets, osteomalacia, tumors, and arthritis;

- Leg-length discrepancy

- Leg injury

- Obesity: obese children have been shown to having increased risk of vaglus knees

If all other traumatic, pathologic, or congenital causes have been ruled out, it may be idiopathic valgus.

Valgus knee treatments

There are various options available for treating valgus knees, but if you have a little bit of valgus, it may not require treatment. If the reason for the problem is related to nutrient deficiencies or disease processes, these underlying disorders will need to be addressed, along with any direct treatment for the knee itself.

Age can be a major factor in what type of treatment should be used since there’s an ideal ‘window’ for certain treatments, such as surgery and orthotics..

Orthotics

Orthotics are used to change mechanics and redistribute force in the knees and feet. These include foot orthotics as well as ‘unloader’ knee braces, which has been shown to reduce knee pain. However, the evidence is unclear about whether it can improve movement and reduce leg knee stiffness

Among children, braces and foot orthotics may be inadequate, ineffective, and unnecessary in changing valgus knees. For people with knee arthritis, orthotics does not seem to influence biomechanics or the progression of arthritis, but it may reduce pain and the ability to do activities of daily living.

Exercise

As shown earlier, although exercise is often recommended to treat valgus knees, there’s very little evidence directly relating weak hip muscles with knee valgus. However, exercise programs may still be helpful in improving gait, strength, and range of motion.

And so, exercise programs that gear towards correcting dynamic valgus can be an effective treatment for PFPS. Exercises specifically aimed at changing the control, strength and use of the muscles around the hip have been found to be effective for correction of dynamic knee valgus.

Manual therapy

Manual therapies, like massage therapy, chiropractic, or osteopathy, are often paired up with exercise programs for issues associated with knee malalignment.

Generally, manual therapy should be geared towards assisting patients with pain and mobility and supporting an active lifestyle. There’s no plausible basis to believe that passive manual therapy can provide any type of long-term change to the alignment or structure of any joint, especially a large, load-bearing joint such as the knee.

Very little research specifically deals with manual therapy as a treatment for knee misalignment. The available research tends to be related to treatment of arthritic symptoms that are sometimes associated with misalignment.

When combined with an exercise program, manual therapies show promise in the short-term management of painful symptoms of knee arthritis and may contribute to short-term improvements in mobility.

Manual therapy may also produce a short-term decrease in overall sensitivity and central nervous system pain responses. Pain is a complex phenomenon, involving both sensory input from the body and perceptions and responses from the brain and the central nervous system.

Surgery

In cases of severe or progressive valgus knee misalignment in children, surgery can be a safe and effective treatment. The goal of surgery is to control the final position of the joint by influencing growth prior to skeletal maturity.

An open or closed wedge osteotomy may be performed, which involves either inserting or removing a wedge of bone from the femur or tibia to affect the final position of the joint.

Another method used is hemi-epiphysiodesis, which is a technique used to stop bone growth on one side temporarily or permanently. This approach is used for correction of leg length discrepancy as well as valgus or varus deformities.

Various ways of hemi-epiphysiodesis are used to inhibit and guide growth, including stapling, or surgical placement of a metal device attached across the growth plate. Patients may get total correction with relatively low complication rates using modern surgical techniques. When the desired alignment is achieved, the hardware is removed.

Surgery may also be considered for patients with severe arthritis associated with a valgus alignment. There’s a significant incidence of need for reoperation in this patient population.

Surgical and rehabilitative downtime, and potential surgical complications, should be seriously weighed against the low possible potential of this surgery to delay total knee replacement in cases of severe arthritis.

Final thoughts

Remember that in most cases of mild knee valgus is not likely to cause major problems. When I did my first marathon many years ago, I was surprised to see how my body looked in action. At the beginning of the race, I was dismayed because I saw everyone was running past me. Young, old, heavy, lean—every body type and description seemed faster and more athletic than me. I found myself at the very back of 11,000 people running that day.

As I continued, I marveled at the variation in body sizes, shapes, and especially gait patterns and biomechanics of the tired runners in front of me. Many participants had what might classically be considered ‘poor’ biomechanics. People were running with hunched shoulders, knock knees, scoliosis, or no movement at all between hips and shoulders in gait. Remember, anybody I was looking at was running in front of me, so I guess they were running faster than I was!

This experience highlighted the importance of being active and not giving too much weight to the importance of biomechanical perfection. Seeing people (including myself) with less than perfect bodies and alignment achieve this impressive feat of athleticism and determination made me realize what we do with our bodies can be just as important as our physical structure and mechanics.

Frances Tregurtha, RMT

Frances has been a registered massage therapist in Ontario, Canada, since 2000, and she is working toward completion of a diploma in manual osteopathic practice.Her clinical background includes private practice, long-term care, and palliative work, as well as motor vehicle injury rehab and work with traumatic brain injury patients.

She currently works in two clinics, one of which is a multidisciplinary setting focusing on women’s health and pediatrics.

Outside of work, she can be found with her family and dog, cooking, gardening, camping, hiking, beach-going, and squeezing in a moment here and there for yoga and a scenic jog.