Patellar tracking disorder refers to patella (kneecap) moving out of place when you bend or extend your knee. Many physical therapists and other clinicians believe that this “imbalance” is the cause of most types of knee pain, such as patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS).

But do you really need to fix your knee tracking? Is patellar tracking disorder actually a primary cause of knee pain? Should you even worry about it?

What is patellar tracking?

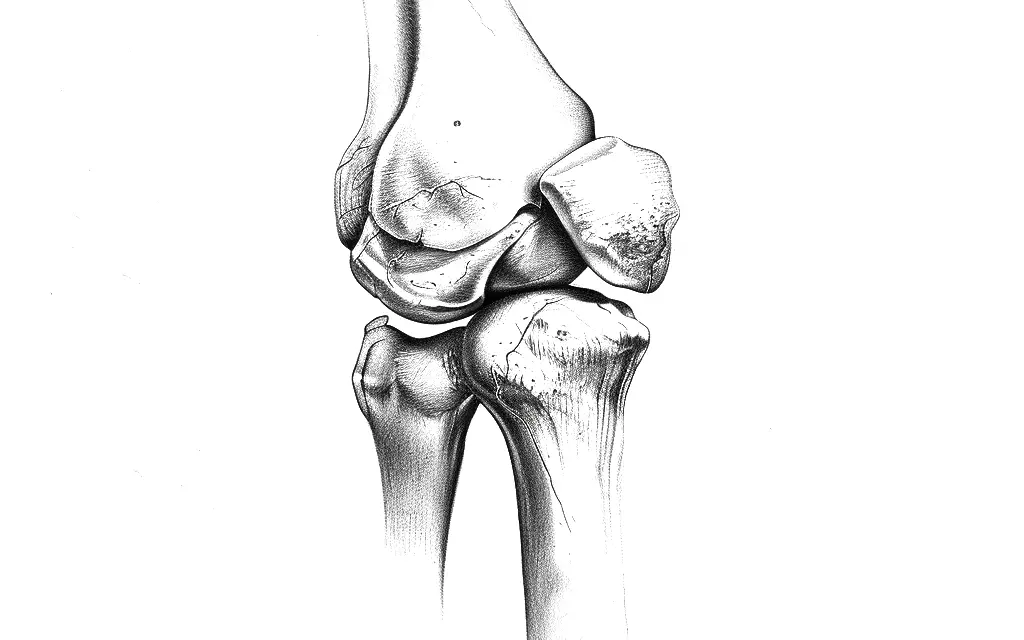

When you extend your knee, your thigh muscles (quadriceps) pull the patella toward the femur at the trochlea, which is a groove in the front of the femur.

When you bend your knee, the hamstrings pull the tibia back and the patellar tendon pulls the patellar away from the trochlea. The kneecap glides slightly side to side as the knee moves. This is not the same as patellar subluxation, or dislocation, of the kneecap.

Causes

Some research finds patellar tracking disorder are caused by multiple factors, including:

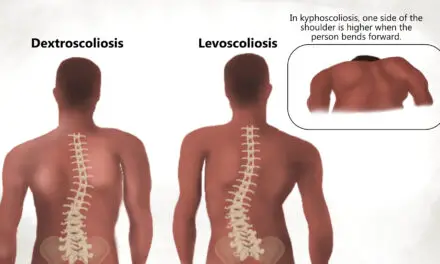

- Weak hip external rotators and abductor muscles, which causes the knee to internally rotate.

- Being female: women are more likely to have PFPS than men.

- Delayed activation of the vastus medialis muscle of the quadriceps. This may cause knee valgus or increase the degree of the Q-angle, which is the angle between the femur and an imaginary line running from the kneecap to the tibia.

However, none of these factors show a direct causal relationship between knee pain and knee misalignment. In fact, research has shown that many people’s knees have found high variability of kneecap positions among healthy knees and osteoarthritic knees.

In the osteoarthritic knees study, researcher Henrik Behrend and his colleagues pooled data from eight studies and measured various angles of the patella, tibial tuberosity, trochlea, and the trochlear groove. They found that not all studies were consistent with what was measured and had “high variability of all measured values” of the patellofemoral joint in the combined studies.

For example, the sulcus angle of the trochlea has an average of 130 degrees with standard deviations from 6.5 to 10 degrees. That means a person’s osteoarthritic knee could range from around 120 degrees to 140 degrees.

“[Patellofemoral] alignment is extremely variable in osteoarthritic knees,” lead researcher Henrik Behrend and his colleagues wrote. “A more precise knowledge of the complex relationship between the patella and the trochlea may help to better diagnose [kneecap] malalignment in patients considered for [total knee arthroplasty] to reduce the risk of anterior knee pain after a knee surgery.”

This means that people with good patellar tracking could have knee pain and poor stability and function, while those with poor tracking could have no pain and can still function well. Thus, patellar tracking alone is a poor predictor for knee pain and function.

In the healthy knees review, the story is similar. After the same researchers reviewed 15 studies, they used the same measurement techniques as the osteoarthritis review and could not find any “normal” range of knee tracking. Thus, such a “normal” range is “unknown.”

For decades, researchers have used different angles to identify patellar tracking disorder, but so far, there is no consensus of what is “normal” knee tracking. Image: Nick Ng.

Symptoms

The symptoms of patellar tracking disorder are similar to PFPS. These include:

- Pain when you bend your knee (usually at the front of the knee).

- Knee instability or feeling “loose” like your knees will give out when you stand or walk.

- Popping or cracking sound when you get up from a sitting position or climbing stairs.

- Severe pain and swelling if the kneecap is completely dislocated, with the inability to bend or straighten the knee.

As previously mentioned, patellar tracking is not indicative that you may have knee pain, instability, or these symptoms.

Research problems

Research in patellar tracking disorder has several major issues that can mislead clinicians and patients about its causes, which may lead to unnecessary treatments and higher costs for patients.

Behrend and his team pointed out that the type of imaging used, how the patellofemoral joint was measured, and imaging protocols can affect the measurement results and how the studies are interpreted.

For example, a Canadian study that used a computed tomography (CT) scan to measure a group of healthy women’s patellar tilt angle with their knee fully extended had an average of 0.86 degrees with a standard deviation of nearly 5 degrees.

A Japanese study that had measured knees with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with the same leg position from young, healthy volunteers found an average of 0.645 degrees with a standard deviation of 0.448 degrees. This is a huge difference between both the Canadian and Japanese populations.

Behrend and his colleagues wrote that race may be a factor in the differences of these measurements. Since there is some overlap in knee misalignment between healthy and osteoarthritic knees, clinicians who base their knee tracking literature like the Canadian study may mistake healthy, asymptomatic people likely to have knee pain.

Similarly, a team of researchers from the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, reviewed 40 patellar tracking studies and found that the studies used too many different methods, which makes it difficult to compare results and understand what causes PFPS.

Even though their analysis showed that maltracking can help diagnose knee pain, the variety of ways to measure it and not controlling other factors make it hard for them to define which measurement method is. Scientists and doctors need to comply with “specific standards for anatomic and outcome measures to “establish methodological uniformity,” they wrote.

For example, while they found an association between quadricep activation and knee pain and patellar tracking, the studies have varying degrees and types of quadriceps contraction, which may affect the measurements and outcome interpretation. For example, static contraction of the muscles would likely produce different pain response and the patellar tilt than contracting the muscles dynamically where the knee bends and extends repeatedly.

Although the review suggests that quadriceps activation may play a role in PFPS, recent research has shown otherwise.

A U.S. and Taiwanese study found “no difference in absolute and normalized individual muscle volumes between individuals with and those without [PFPS].” In other words, the lack of certain quadriceps muscles firing is not a primary cause of this type of knee pain.

Grant and her colleagues concluded that their study “exposed large methodological variability across the literature, which not only hinders the generalization of results, but ultimately mitigates our understanding of the underlying mechanism of [PFPS].”

Diagnosis

A doctor or physical therapist can diagnose patellar tracking disorder using several methods:

- Physical Examination: The clinician assesses your knee’s range of motion, looks for signs of swelling, and checks the alignment of the kneecap. They might also perform specific maneuvers to see how the kneecap moves during bending and straightening of the knee.

- Patient History: The clinician asks about your symptoms, such as pain location, onset, and activities that aggravate or relieve the pain. They will also inquire about any previous knee injuries or surgeries.

- Imaging Tests: Patellofemoral pain and instability often requires imaging in medical practice, which are detected before osteoarthritis develops.

- X-rays: To check the position of the kneecap and look for any bone abnormalities.

- MRI (magnetic resonance imaging): To get detailed images of your knee’s soft tissues, including cartilage, ligaments, and muscles.

- CT scan (computed tomography): To provide detailed images of the knee bones and help assess the alignment of the kneecap.

- Dynamic movement analysis: Sometimes, the doctor may use video analysis to observe the movement of the knee and kneecap during different activities, such as walking or squatting.

- Q-angle measurement: A large Q-angle may indicate misalignment issues, but this isn’t always the case.

- Patellar tilt test: The clinician manually tilts the kneecap to see how easily it moves and to check for any excessive tilt that could indicate a tracking problem.

- Apprehension test: The clinician gently pushes the kneecap to the side to see if the patient feels discomfort or apprehension, indicating potential instability or maltracking.

These methods together help the clinician to diagnose patellar tracking disorder more accurately and develop an appropriate treatment plan. One study of 32 knee surgeons found that they accurately identified patellar maltracking in video 68% of the time and correctly graded the severity of the maltracking between 48% and 68% of the time. For a more accurate diagnosis, this needs to be combined with other tests.

Treatment

Treatment for patellar tracking disorder can be non-surgical or surgical, depending on the severity of the condition and the response to initial treatments.

Non-surgical treatments

Many clinicians may recommend conservative treatments first because they could manage symptoms and improve knee function without the risks and recovery time associated with surgery.

Exercise

Strength training and stretching may be used to alleviate patellar maltracking symptoms by strengthening the quadriceps, hamstrings, and the knee joint. The type and method of exercise depend on the cause of the patellar maltracking.

Sample exercises include:

- Seated leg extension

- Squats

- Hamstring curls

- Lunges

- Step-ups

- Nordic hamstring curls

- Balancing exercises

Research finds that exercises that combine hip and knee strengthening are better than knee exercises alone to reduce knee pain and improve patellar alignment—even though both types of exercises can benefit.

A 2023 systematic review of seven studies with a total of 282 patients with a knee dislocation found that there was “no statistically or clinically significant difference” between a general exercise program and a specific exercise program after 12 months of training.

Specific exercises aim to target the vastus medialis obliquus (VMO) muscle, but this is not possible because all quadriceps are innervated by the femoral nerve. “These two parts were not separated by [a] distinct fascial plane and no separate nerve supply to label it anatomically separate entity,” the authors wrote.

Bracing and knee orthoses

Bracing and knee orthoses could be effective treatment options for patellar tracking disorder and PFPS, but the scientific evidence is mixed on whether it provides additional benefit when combined with exercise therapy. One study of 136 people found that adding knee bracing to a home exercise program did not improve symptoms more quickly compared to doing the exercise program alone.

A 2023 systematic review found that benefits from bracing and orthoses “have not been confirmed by clinicians and scientific investigators.” The researchers reported that the three orthosis types (unloader, patellofemoral, and knee sleeves) show that “clinical efficacy is still elusive” because of the different methods used by other researchers.

However, patients may believe that braces and knee orthotics help keep their kneecap aligned properly when they move, which may be helpful during the initial treatment phase when pain levels are higher and they may be more apprehensive about putting weight on their knee.

Taping

Taping cannot realign the kneecap, but it could reduce pain and improve movement, according to a 2015 study of 11 studies that used either McConnell taping or Kinesio taping.

Scientists aren’t sure exactly how taping helps with pain for people with PFPS, but most studies agree that both types of taping touch skin sensors and help the knee sense movement better. This extra feeling sends signals to the brain that could help reduce pain. This process might be explained by the gate control theory, in which the spinal cord contains a neurological “gate” that either blocks or allows nociceptive signals to pass to the brain.

Related: Skin Sensory Receptors: How Context Affects Touch Response

Surgical treatments

Your physician or physical therapist may recommend surgery if conservative treatments didn’t work for you after six months or if a tear or knee dislocation is so severe that surgery is a last resort.

Lateral release

Lateral release helps improve patellar tracking disorder by cutting tight ligaments on the outer side of the kneecap, allowing it to move more freely and align properly.

The procedure involves making small incisions around the knee and using specialized instruments to cut the lateral retinaculum, which is the tight ligament that pulls the kneecap outward. This reduces the lateral pull on the kneecap and helps it track correctly within the groove of the femur.

Orthopedic surgeon Hussein Elkousy of Houston, Texas, identified several potential long-term complications of lateral release:

- Weakening of knee extension movement

- Creating medial patellar instability

- Worsening patellofemoral pain

- Burning of the skin from an aggressive release

- Failing to correct the original disorder. The only real short-term complication is hemarthrosis

Research has found that lateral release may not always improve patellar tracking symptoms. In a 2011 study of 1,859 patients who had undergone total knee arthroplasty (TKA), 154 of these patients (8.3%) had lateral release. Patients with a low American Knee Society Score before surgery, more valgus deformity, and a surgeon’s decision increases the likelihood of getting a lateral release.

There was no significant difference in knee function and symptoms between the lateral release group and the non-lateral release group in the long term.

Likewise, a 2023 study of 198 patients with TKA found that there was “no difference in terms of improvement of clinical and radiographic scores” between those with a lateral release and those without after a one-year follow up.

Medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL) reconstruction

MPFL reconstruction is a surgical procedure that repairs or replaces the ligament to stabilize the kneecap and prevent it from dislocating. It involves harvesting a tendon graft, creating tunnels in the femur and patella, positioning and securing the graft to stabilize the kneecap, and closing the incisions, followed by physical therapy for recovery.

A 2023 systematic review of three studies with a total of 133 children and teenagers with knee instability found that those who had MPFL reconstruction had a 5% rate of knee re-dislocation and a subluxation rate of 2%. While the rate of complications is low, the researchers warned that the sample size was low, and the studies used different graft types and surgical techniques, making the results less reliable. There also wasn’t enough data to compare different groups. The average follow-up time was about 38 months, so the review only shows how well allografts for MPFL reconstruction work in the short to midterm.

For young adults, another systematic review found that MPFL reconstruction “synthetic graft may be reliable and feasible” for patients with chronic and recurrent knee instability.

Like the previous review, the researcher noted that there weren’t many studies about using synthetic grafts for MPFL reconstruction, which means there weren’t many procedures to analyze. Most of the studies were small and looked back at past cases, which made the results less reliable. Some studies also looked at MPFL reconstruction with other alignment surgeries, but there wasn’t enough information to compare different groups. The study also did not include patients with acute knee instability.

Such studies “must be interpreted with caution,” the researchers wrote.

Tibial tubercle transfer

Tibial tubercle transfer is a surgical procedure that repositions the bony attachment of the patellar tendon to improve kneecap alignment and stability. It involves cutting and repositioning the bony prominence where the patellar tendon attaches to the tibia.

In a 2023 systematic review of four studies with a total of 346 young adults, the researchers found that patients with MPFL reconstruction with tibial tubercle transfer “achieved substantial improvements” in two scoring methods than those with MPFL reconstruction alone. However, they warned that those with both types of procedure have higher risk of complications, such as re-dislocation and instability, wound infection (two patients), and fixing a screw (13 patients).

Despite the endorsement of conservative treatments of patellar tracking disorder and knee pain, a 2023 systematic review found that surgery tends to have lower incidences of kneecap re-dislocation than conservative treatments.

Also, the researchers reported that conservative treatment research are “often biased, lacking in description or not reporting exactly the type, duration and structure of the physical sessions, which limit translation into the clinical practice.”

Takeaway

Remember that having misaligned patellar tracking doesn’t necessarily cause knee pain. Current evidence shows that people with proper patellar tracking can still experience knee pain, while those with poor tracking might have no pain and function just fine. Always consult with your clinician to see which treatment and recovery methods are best for you.

Further reading

Why Does Bending Your Knee Hurts and What Can You Do?

What Is Pain and Why Do We Feel It?

A native of San Diego for nearly 40 years, Nick Ng is an editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine, an online publication for manual therapists and the public who want to explore the science behind touch, pain, and exercise, and how to apply that in their hands-on practice or daily lives.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a B.A. in Graphic Communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014.

When he is not writing or reading, you would likely find him weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, or exploring new areas to walk and eat around Southern California.