The gate control theory of pain revolutionized how pain is understood and shaped how physicians and other healthcare professionals treat and explain pain to their patients.

Developed by psychologists Ronald Melzack and neuroscientist Patrick David Wall in 1965, the gate control theory challenged more than three centuries of dogma about how pain works, such as the degree of tissue damage is a reflection of how intense the pain is.

It was built upon by several key theories in the 19th and early 20th centuries that questioned the existing idea about pain. In 1989, Melzack expanded the gate control theory with the neuromatrix theory of pain, which includes the affective and cognitive factors that make up our pain experience.

Despite the advancement of our understanding of pain, many manual therapists and their education still default to the “tissue damage equals pain” mentality.

A basic understanding of the gate control theory—what it is, its relevance to clinical practice, and faults—can help us find a better treatment and weed out false ideas that can harm patients.

How does gate control theory of pain work?

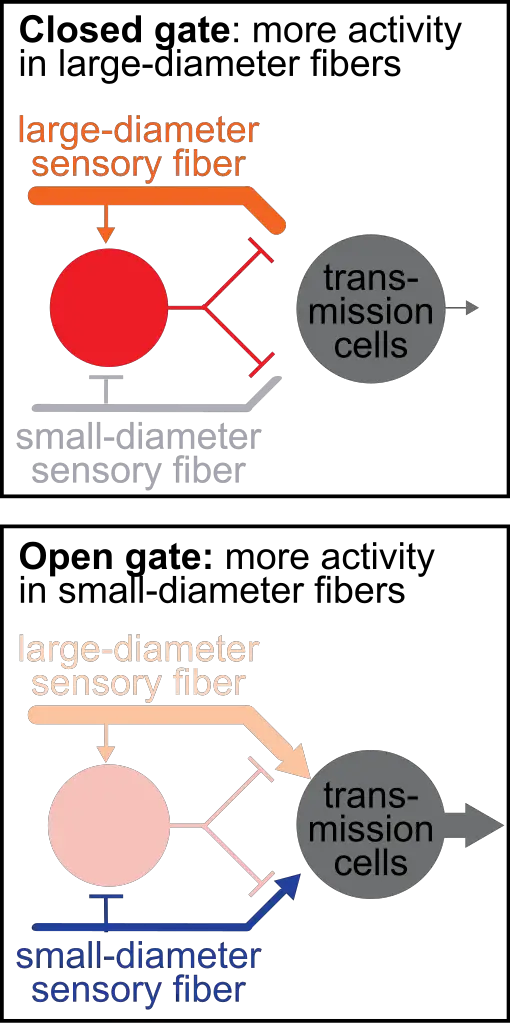

The gate control theory of pain states that non-painful stimulus, usually from the peripheral nerves, can close the of the neurons in the spinal cord that relay messages to the brain.

Such stimulus overrides a painful stimulus, which is one explanation why you instinctively rub a painful area when it hurts like stubbing your toe and having an achy lower back, according to Melzack.

According to the gate control theory of pain, the system works like a “gate,” which can be opened wide to increase the flow of neural messages in from the stimulus or be closed to decrease these messages.

If the painful stimulus is intense and frequent enough, it may open the “gate” and the messages are relayed to the brain where they’re processed in the thalamus and the somatosensory cortex as pain. If the gate is closed, then these messages are blocked and—theoretically speaking—no pain is felt.

Gate control theory example

Since the 17th century, pain is believed to be linear process where an external stimulus, such as a knife cut, sends messages through neural pathways from the skin to the brain where they’re processed as pain.

However, some observational studies in clinical settings find that people respond differently to the same stimulus that’s supposed to be painful.

For example, two people can experience the same level of intense heat on their hand, yet one feels more pain than the other. Thus, the gate control theory states that pain is not a direct stimulation of pain receptors; instead, it’s a perception stemming from interactions among different neurons in the skin and spinal cord.

So going back to the knife cut example, two people with the same degree of injury might experience and respond very differently. Their response would be modulated with context and previous experience of such injury.

Biology and neuroscience of pain gating

Earlier theories, such as the summation theory and intensity theory of pain, were already moving away from the Descartes’ explanation of pain. These theories focus away from the peripheral nerves and toward the spinal cord where gate control theory evolved.

There are three main types of nerve fibers—nociceptors—are involved in pain sensation and perception in the gate control theory: A fibers, C fibers, and “gate” interneurons.

A fibers come in two types: A-delta and A-beta. A-delta fibers are smaller in diameter than A-beta, and both types are myelinated, which are able to transmit neural impulses quickly.

C fibers are unmyelinated, which transmit slower impulses. The interneurons are specialized neurons that control what messages get relayed or not. They’re connected to the thalamus, the egg-shaped section in the middle of the brain that process motor movements and sensory information.

From there, the impulses are sent to the somatosensory cortex, which gives us an awareness to where the stimulus is coming from.

Both A fibers and C fibers go through the substania gelatinosa in the dorsal horns of the spinal cord, which is where Wall hypothesized the gating takes place.

Stimulation of A-beta fibers can cause the neurons to block transmissions to the brain (close the gate) and pain is not experienced, while the C and A-delta fibers facilitate and relay transmissions (open the gate).

Because the smaller fibers transmit slower and longer impulses, they can make us more sensitive to pain, often in the form of dull, numbing, or achy pain. This is basis the of ascending modulation.

Image: John Tuthill

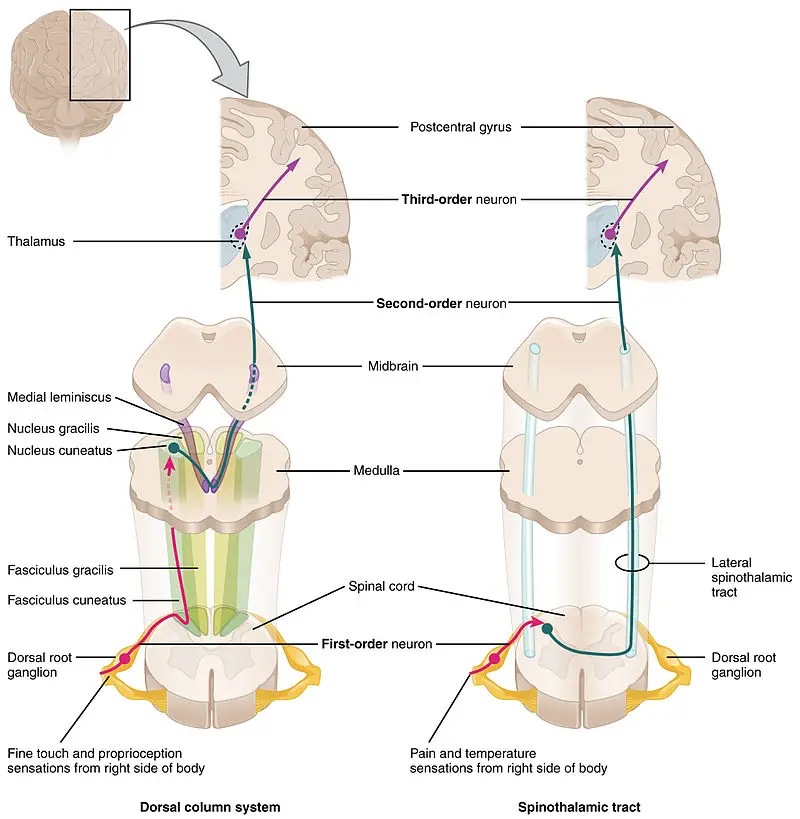

Ascending inhibition consists of two pathways that send messages from the peripheral nerves to the brain: the leminscal and spinal thalamic pathways.

In a nutshell, all A fibers connect to the dorsal horns in the leminscal pathway that detects touch, proprioception, vibration, and two-touch discrimination.

At the dorsal column nuclei in the brain stem, the pathway crosses to the opposite side of the brain in the thalamus, which sends messages to the somatosensory cortex.

The spinal thalamic pathway, which detects pain, touch, and temperature, consists of C fibers and A-delta fibers, which goes directly from the dorsal horns to the thalamus on the same side of the spinal cord and brain.

However, this explanation is incomplete because the brain also gets to decide how the transmissions from the nociceptors are interpreted, which also are processed in the spinal cord.

Melzack and Wall proposed what seemed like an early description of descending modulation, where neural impulses from the brain can “close the gate.”

Image: OpenStax College, Anatomy & Physiology, Connexions Web site. http://cnx.org/content/col11496/1.6/, Jun 19, 2013.

They said that when the ascending impulses reaches the brain, neurons in the brain rapidly transmits down to the spinal cord to open or close the gate.

The brain process is influenced by various cognitive and emotional factors, such as prior experience to pain, the meaning of pain, beliefs about pain. Therefore, the gate control theory is the first theory that recognizes psychological aspects that influence our pain experience.

Another gate control theory example

Let’s say you’re walking on the beach barefoot and you step onto a piece of glass which cuts into the skin.

Immediately, your peripheral nerves in your foot shoot an intense message to your spinal cord via the fast A fibers, which opens the “gate” and allows the message to go to the brain. The brain may interpret the message as danger, which would give rise to our pain experience. If so, you would feel a sharp pain.

You would examine your foot, remove the glass, and massage the area. By then, the pain would feel dull or seething.

This sensation comes from the slow C fibers, which transmit a lower intensity over a longer period of time. The gentle stimulation of the massage is an attempt to override the pain stimulation by shutting the gate.

This stimulates the dorsal column–medial lemniscus pathway (DCML) which closes the gate. With less pain or danger, you can walk to get first aid for your injury.

Gate control theory: psychology and mental factors

Melzack observed that some patients who had a limb amputation had phantom limb pain while some did not. He hypothesized that such variations in the pain experience would have a combination of psychological and physiological factors.

Such psychological factors include beliefs, thoughts, and emotions. However, prior to the gate control theory, psychological factors were dismissed by most medical professionals.

He wrote, “In the 1950s, there was no room for psychological contributions to pain, such as attention, past experience, and the meaning of the situation. Instead, pain experience was held to be proportional to peripheral injury or pathology. Patients who suffered back pain without presenting signs of organic disease were labeled as psychologically disturbed and sent to psychiatrists.”

The gate control theory doesn’t specify how these psychological factors work to open or close the gate, but many research since the 1960s have revealed some clues on how our mind and emotions affect how much pain we experience.

By the mid-1970s, the concept of biopsychosocial of health emerged from the writings of psychiatrist George Engel that emphasized looking at the whole instead of only one aspect of disease contribution.

While the gate control theory focused on the basic neurophysiology and anatomy behind pain, the biopsychosocial model “views illness as a dynamic and reciprocal interaction between biologic, psychological, and sociocultural variables that shape the experience and the response to pain,” wrote Dr. Dennis Turk, who is the director of the Center for Pain Research on Impact, Measurement, & Effectiveness (C-PRIME) at the University of Washington School Medicine.

The biopsychosocial model flips the paradigm where people in pain are actively making sense of their pain experience that influences emotions, behavior, and physiology. They’re not passive receivers of physiology.

In fact, this paradigm shift led some pain researchers to expand the gate control theory of pain with three major psychological factors that are currently recognized as predictable and reliable factors.

Expectations today predict tomorrow’s pain

Expectations can play a huge role in how we perceive pain, a necessity to our survival. This is based on our prior experience to pain, such touching a hot stove, which helps us predict the consequences of our actions and behaviors. The pain we experience would likely change our behavior to avoid the event from happening again.

Many studies reveal that high pain expectancy leads to higher pain experience and avoidance behavior, which reduces coping behavior to build resilience.

In 2017, a team of psychologists from Arizona State University replicated previous diary studies on people with chronic pain. Their study involved people with either fibromyalgia or rheumatoid arthritis.

In the arthritis group, higher pain expectations today results in more pain the next day.

In the fibromyalgia group, the results are very similar, where pain expectancy in the afternoon that interfered with their activities are high predictors of pain in the next morning and afternoon.

The researchers said that the high pain expectancy increases anxiety and hyperviligance, which causes “neural substrates associated with affective and cognitive processing” to activate.

Catastrophization and pain

Catastrophization is a negative thought process where we think of the worse possible outcome and consequences. Three primary symptoms include ruminating the problem, magnifying it, and feeling helpless.

For example, if you have severe low back pain that you cannot even put on your own clothes or get out of bed, you may think this pain might last a long time, maybe forever.

You may think that you cannot go to work or an important social event, which can affect your income, how people may perceive you, and your independence and mortality.

A 2019 meta-analysis examined 85 observational studies on pain catastrophization with a total of more than 13,000 participants. Although the data show there’s a positive association between the degree of catastrophization and higher pain intensity and disability, most of the trials’ quality were “very low,” due to different ways of measuring pain, different populations, poor follow-up, faulty measurements of exposure and outcome, and failure to control confounding factors that could skew the perception of cause and effect.

Despite the low-quality studies, the consistency of the results indicates that higher catastrophization is a reliable predictor for higher pain experience.

Depression, anxiety, mental health

Catastrophization and high pain expectancy often walk hand-in-hand with depression and anxiety and can be almost inseparable.

Thus, these common mental health problems can affect how people can experience varying levels of pain due to different ways the brain reorganizes its neural connections and adaptation (neuroplasticity).

For example, chronic pain can reduce the amount of dopamine made in the mesolimbic pathway of the brain in humans and animals, which can cause less motivation and a rewarding feeling.

This is also a common symptom of depression when we no longer find joy or fulfillment in things that we used to enjoy.

Mechanisms the brain that regulates behavior and emotions can deviate from normal management by having a reduced production of some neurotransmitters, such as serotonin and norepinephrine.

Research behind the gate control theory

Like all theories in science, the gate control theory was developed from previous research in prior to the 1950s that challenged the Descartes’ take on pain, which has been accepted for three centuries.

Because it revolutionized how physicians treat patients and how pain is taught among various healthcare professions, the gate control theory overshadows previous theories that made Melzack’s and Wall’s work possible. They should be given credit.

Intensity theory of pain

Stemming from the specificity theory of pain, which states that there’s a straight-forward pathway between the painful stimulus and the brain that results in the pain experience, the intensity theory postulates that a single noxious stimulus does not always elicit pain.

This idea was made several times throughout human history, going as far back as Plato in his oeuvre Timaeus in the 4th century B.C. He described pain not as a sensory experience, but “as an emotion that occurs when a stimulus is stronger than usual.”

In 1859, German physician Bernard Naunyn conducted experiments on patients with syphilis who had a degenerated dorsal column. He performed “repeated tactile stimulation” just below touch perception.

The patients felt pain after they received 60 to 600 times stimulations where the initial innocuous stimuli became painful. With this finding, pain research began to move toward the spinal column.

Pattern theory of pain

Researchers who followed the specificity and intensity theories were searching for specific skin receptors that detect specific types of pain, such as heat and cold.

However, the pattern theory of pain, proposed by American psychologist John Paul Nafe in 1929, ignores this and proposes that receptors on our skin that respond to heat, cold, and both harmful and non-harmful stimuli can produce a painful or non-painful sensation. This is determined by the firing pattern and the intensity of the neural impulses that are sent to the brain.

For example, a punch to the face produces a different stimulus—and very likely pain—than a caress to the face because of the differences in intensity and timing of the touch. Melzack wrote that the pattern theory “set the stage for the gate control theory.”

Summation theory and sensory interaction theory of pain

The summation theory shows that small peripheral nerves converge at the gray matter of the dorsal horn, a site where German physician Alfred Goldscheider thought it’s an area where sensory stimuli is processed.

William K. Livingston, who was an American neurologist, expanded the summation theory in 1943 by postulating that neural circuits in the dorsal horn continue to “echo” in pain long after an injury has healed.

The sensory interaction theory, made by Dutch neurosurgeon Willem Noordenbos in the 1950s, suggested that large fibers (like the A fibers) inhibit small fiber from turning on “central transmission neurons” in the dorsal horn that transmit to the brain. From here, Melzack and Wall combined both theories—with their own research—to form the gate control theory.

Gate control theory and manual therapy

The gate control theory of pain can help manual therapists think about their patients’ painful condition beyond anatomy. (Photo courtesy of Shin Iwayoshi, DNM Japan.)

The gate control theory is a major piece of a bigger puzzle of understanding pain. It doesn’t mean that massage therapists and other manual therapists have to change a lot of what they do.

Instead, changing the narrative of pain from the outdated biomechanical and biomedical model of pain (e.g. “tight” psoas causes low back pain) to the biopsychosocial model of pain would be an important step.

While it’s not perfect, the gate control theory gets us out of the separation of the body and mind that had permeated in healthcare and research for more than three centuries. Therefore, when you work with patients or clients in pain, consider the many factors that contributes to their problem. It steers your hands-on work and communication away from modality thinking to more listening and asking questions about their patient or client.

Further reading on pain

Pain Science 101 for Massage Therapists

Why Massage Therapists Should Understand How Pain Works

A native of San Diego for nearly 40 years, Nick Ng is an editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine, an online publication for manual therapists and the public who want to explore the science behind touch, pain, and exercise, and how to apply that in their hands-on practice or daily lives.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a B.A. in Graphic Communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014.

When he is not writing or reading, you would likely find him weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, or exploring new areas to walk and eat around Southern California.