Jumper’s knee has long plagued athletes regardless of sport or skill level. It typically affects young athletes participating in high-impact sports, such as basketball, volleyball, track and field, tennis, and football.

NBA’s Dwayne Wade and Kyrie Irving had it, and so did Super Bowl’s most valuable player Julian Edelman and baseball superstar Vladimir Guerrero. It’s been reported that nearly every player on an NBA roster gets treated for jumper’s knee, or patellar tendonitis, on a daily basis during the season.

One-third to one-half of these athletes will reportedly face jumper’s knee at some point during their athletic career.

First described in 1973, jumper’s knee is one of the most well-studied overuse conditions, which can include pain at the quadriceps insertion, distal pole of the patella, or the tibial tubercle insertion.

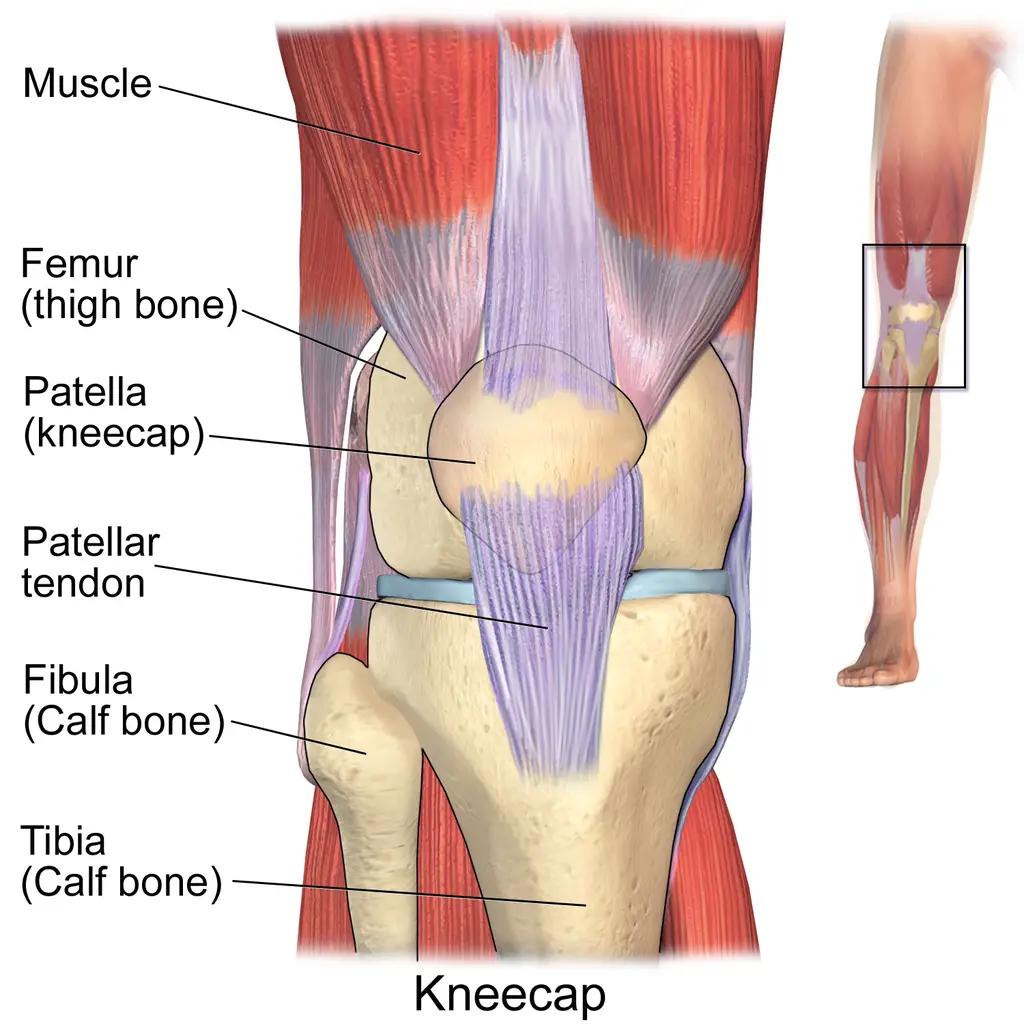

Anatomy of the kneecap region

The anterior anatomy of the knee is called “extensor mechanism,” which is made up of the quadriceps muscles and tendon, the patella, patellar tendon, and retinaculum, which is a band of fascia that support the knee on either side of the kneecap. Injuries to this area can occur because of trauma, overuse, or degenerative changes.

Blausen.com staff (2014). “Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014”.

Symptoms of jumper’s knee

People with jumper’s knee typically experience pinpoint front knee pain and tenderness at the distal pole of the patella. The diagnosis is generally made in the clinic but may be supported by radiographic or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

There are several classification systems for grading the severity of jumper’s knee.

The first, described by Dr. Martin E. Blazina, who is also credited with being the first to define the condition, divides it into three clinical phases:

- First phase: pain post-exercise

- Second phase: pain at the beginning and end of activity but not during

- Third phase: pain during and after activity

- A fourth phase was added later to represent complete rupture of the tendon.

The second classification system, developed by the Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment, is made up of a series of eight questions with a total score of 100. Higher scores indicate less severe cases of tendinopathy. This serves to improve the measurement of severity and response to treatment.

A third scale, based on duration of symptoms, is widely used. In this system:

- “Acute” is used when symptoms have been present for less than six weeks

- “Subacute” describes symptoms present between six and 12 weeks

- “Chronic” is used for symptoms lasting three months or more

The average duration of symptoms can be as long as 19 months in recreational athletes and 32 months in elite athletes. Nearly one-third of those with jumper’s knee are unable to return to sport within six months and more than half don’t return at all.

Although jumper’s knee may involve any portion of the patellar tendon, the proximal patellar tendon at its insertion is most often affected.

The most common reported symptoms are:

- Pain in the patellar tendon area

- Knee swelling

- Limitations when running, jumping, squatting, sitting, stair climbing, or walking.

Resting pain isn’t typically associated with jumper’s knee. Symptoms are often long lasting and may lead to disability. A detailed history and thorough physical examination are keys to detecting jumper’s knee, and your clinician should ask about your sport participation, practice and competition schedules, field/court position, and level of performance.

Causes of jumper’s knee

Common causes of jumper’s knee include:

- Overuse of the knee extensors due to jumping, landing, acceleration, deceleration, and cutting

- Constant repetition within a session

- Too little recovery time between sessions can lead to micro-tearing of the tendon.

There can be intrinsic causes of jumper’s knee as well, such as:

- Lax ligaments

- High Q-angle

- Patella alta

- Overpronation

- Hip pain

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of jumper’s knee is based on a skilled history and physical exam with age being a critical factor in such diagnosis. It’s often seen in adolescents because the injury incurred may be related to excessive stresses to open growth plates.

Disruption of the growth plate can result in Osgood-Schlatter syndrome—a common stress reaction at the tibial tuberosity—or the less common Sinding-Larsen-Johansson syndrome, which is a stress reaction at the inferior pole of the patella). Both which may cause anterior knee pain.

Scans may be used to exclude bony disorders, such as Osgood-Schlatter syndrome or osteochondritis dissecans.

MRI may be used, however, differentiating between high-grade tendinosis and partial thickness tears is unreliable using this imaging method. Diagnostic ultrasound is likely to present a more clear picture in the differentiation of severity.

The differential diagnosis of jumper’s knee seeks to exclude patellofemoral pain, plica injury, osteochondral lesions, bursitis, and fat pad involvement.

- Jumper’s knee can easily be differentiated from quadriceps tendinopathy by the location of the pain (patellar tendon vs. quadriceps tendon).

- Those with patellofemoral pain often experience aggravation of their symptoms with low-load activities, such as walking, running, or cycling, whereas jumper’s knee usually occurs with high-load training.

- Injuries to the plica are characterized by a history of a snapping sensation, which is correlated with tenderness at the plica when it is touched.

- Osteochondral lesions or defects to the lower area of the trochlea or kneecap may mimic patellar tendinopathy in terms of where the pain is, but they will often have joint effusion which indicates injury to the bone and cartilage, which rules out tendinopathy.

- Direct trauma to the anterior knee may also result in injury to any of these structures, which may also rule out injury to the bursae or fat pads.

Treatments

Research has yet to determine a “best” treatment for jumper’s knee. Early recognition and diagnosis can be a helpful management strategy as the condition is often progressive.

Since jumper’s knee is not inflammatory, and the old practice of prescribing non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) has fallen out of favor, they are unlikely to provide long-term benefits.

Exercise

Current evidence suggests eccentric strength training may play a key role in jumper’s knee management. Patients should avoid excessive jumping or high-impact activities.

As pain levels improve, rehab intensity should increase and eventually progress to sport-specific training. Keep in mind that tendinopathies are often hard to manage because they’re slow to respond to treatment.

This delayed treatment response has led clinicians to seek out alternative therapies, such as dry needling, platelet rich plasma therapy, and extracorporeal shock wave treatment, all of which may play a role in managing the pain and symptoms associated with jumper’s knee. But as usual, more research is needed to ultimately determine how well they actually work.

Surgery

Surgery is often the last resort for the most stubborn cases of jumper’s knee. Historically, open surgery had been the gold standard, but recently an arthroscopic approach has grown in popularity.

The procedure includes debridement of the anterior fat pad and patellar tendon, and tenotomies to address persistent tight or shortened fibers of the tendon. Those who undergo arthroscopic, rather than open surgery, tend to return to normal activity more quickly.

As with any medical condition, you should consult with a physician or qualified medical professional to determine the best course of treatment for your condition. This article should not be considered a substitute for professional advice or care.

Do braces and patellar tendon straps work for jumper’s knee?

Braces or straps? Well, it likely depends on the individual. There’s moderate evidence—both scientific and anecdotal—that finds jumper’s knee braces to be useful for some people in some situations.

Severity and duration of symptoms may be the keys in figuring out which brace to use. Those who experience milder pain and symptoms over a short period of time may find the braces more helpful than those with long-standing pain and dysfunction.

It’s also possible that different braces may be useful at different times. If your knee pain occurs mostly during an activity, patellar tendon straps seem to help mitigate pain and symptoms whereas the Reaction brace is generally prescribed for daily use regardless of activity.

At the end of the day, if you’re having pain at the front of your knee, there’s a good chance that a brace can help keep you more active with less pain.

Jumper’s knee exercises

For jumper’s knee, single-leg squats using a decline board have been used because this position is thought to concentrate the load on the patellar tendon. (All photos by Penny Goldberg)

Single-leg squats with a decline board.

Given that jumper’s knee has such a lagging response to treatment, eccentric exercise may be too aggressive for the early stages of rehabilitation.

Also, eccentric exercise has taken a backseat to heavy slow resistance training in the rehabilitation of tendinopathies. A randomized clinical trial comparing the two approaches found heavy slow resistance to be equivalent to eccentric exercise in pain levels and functional outcomes but superior in patient satisfaction.

Recently, a guideline for staging and progression of rehabilitation for jumper’s knee was proposed. The program consists of four stages: isometric loading, isotonic loading, energy-storage loading, and return to sport. Examples of the type of exercises that fit each stage are:

Phase 1: Multi-angle isometrics on knee extension machine or isometric Spanish squats with 70- to 90-degree knee flexion.

Spanish squats.

Split squats.

Phase 2: Isotonic knee extension, leg press, stationary lunges, or split squats.

Isotonic knee extensions: holding a position against a resistance for a period of time.

Phase 3: Hopping and jumping variations, acceleration from standing start, deceleration progressing from two foot stops to single-leg stops and cutting or direction changes.

Double leg jump.

Phase 4: Gradual return to sport-specific training

Simulated layup for jumper’s knee.

During this staged progression, the emphasis should first be changes to load, then progressively increase the load as dictated by pain. Some pain is acceptable during and after exercise but symptoms should quickly resolve.

Careful monitoring for carryover pain (pain the next morning and up to 24 hours after exercise) should be part of the program to ensure the tissues are not being overloaded.

Conversely, too little loading of the tendon may not produce the desired results as the stimulus needs to reach a threshold to create changes in the tendon at the cellular level. The key to success is that load is progressed based on tolerance and monitored using a chosen pain provocation test during each session (e.g. decline squat).

Once all phases are complete and the patient has returned to their desired sport, they should complete a maintenance program using the phase 2 exercises at least twice a week. It’s preferable to choose exercises that are loaded and single-leg, such as split squats and leg press.

Isometrics can be used for their pain-relieving qualities as needed throughout training. It’s critical that you and your therapist identify and address other flexibility limitations and strength deficits while recovering from jumper’s knee.

Jumper’s knee and massage therapy

Despite a lack of evidence supporting its use for tendinopathy, deep friction massage is one of the therapeutic modalities most frequently used for jumper’s knee. Some massage and physical therapists suggest that deep friction massage can reduce adhesions, assist with realignment of collagen fibers in the tendon, and decrease pain, but most of the claims are not supported by current scientific evidence.

A 2020 study found that the immediate reduction in pain intensity was not related to the amount of pressure applied by the massage therapist, which suggests that the deep tissue massage that is typically used may be unnecessary.

Active stretch, or pump massage, may also be used. To perform this technique the patient is seated with their legs dangling over the side of a treatment table.

The therapist applies pressure at the inferior pole of the patella to pin the tendon down while simultaneously “pumping” the lower leg from extension to flexion.

This technique can also be performed where the patient brings their leg from extension to flexion while the massage therapist maintains pressure over the tendon; this may also create reciprocal inhibition of the quadriceps via activation of the hamstrings.

As with any other condition, it’s important that massage therapists treat the patient, not just the anatomy. The knee doesn’t work in isolation, so addressing the soft tissues of the hip, low back, foot, and ankle regions may be indicated.

The high prevalence of jumper’s knee in elite and recreational athletes alike, should keep this diagnosis at the top of the list when evaluating young athletes with knee pain.

Although it’s common (the list of NBA athlete’s alone is about 20 names long and full of All-Stars!), this condition is difficult to manage and requires careful attention to detail in creating a customized approach to load management along with a lot of patience, grit, and hard work.

Penny Goldberg, DPT, ATC

Penny Goldberg, DPT, ATC earned her doctorate in Physical Therapy from the University of Saint Augustine and completed a credentialed sports residency at the University of Florida. She is a Board Certified Clinical Specialist in Sports Physical Therapy.

Penny holds a B.S. in Kinesiology and a M.A. in Physical Education from San Diego State University. She has served as an Athletic Trainer at USD, CSUN, and Butler University.

She has presented on Kinesiophobia and differential diagnosis in complicated cases. Penny has published on returning to sports after ACL reconstruction and fear of movement and re-injury.

Outside of the clinic, Penny enjoys traveling, good cooking with great wine, concerts, working out and playing with her dogs.