Image: Stephanie A. Weyrauch

When I was in graduate school, the diagnosis “femoroacetabular impingement”—or FAI—was a relatively new and unknown phenomenon. While I was spending most of my time examining the relationship between movement abnormalities and the development of low back pain, my friend Davor was investigating risk factors that led to the development of FAI and hip osteoarthritis.

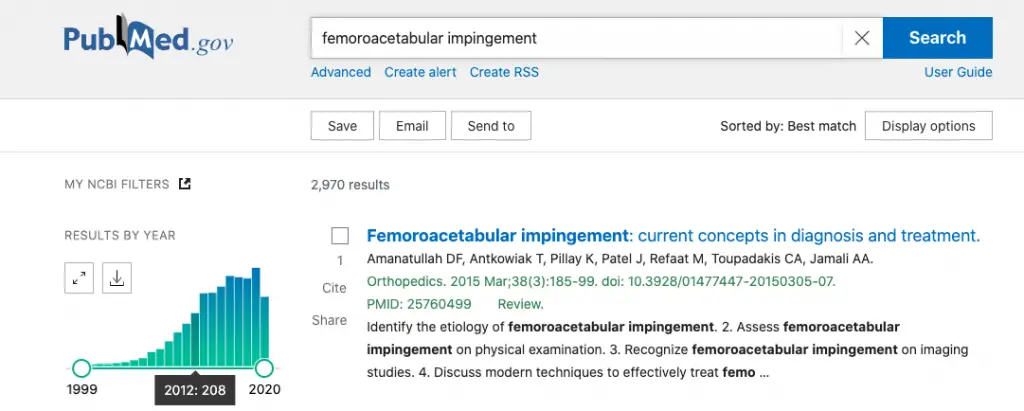

In fact, in 2011, only 165 articles on FAI were published on PubMed—an online database for peer-reviewed biomedical research. Nearly ten years later, scientists and clinicians are still trying to understand the underlying mechanisms that lead to FAI, as well as making sense of the most effective treatments to prevent progression and disability.

Screenshot: Stephanie A. Weyrauch

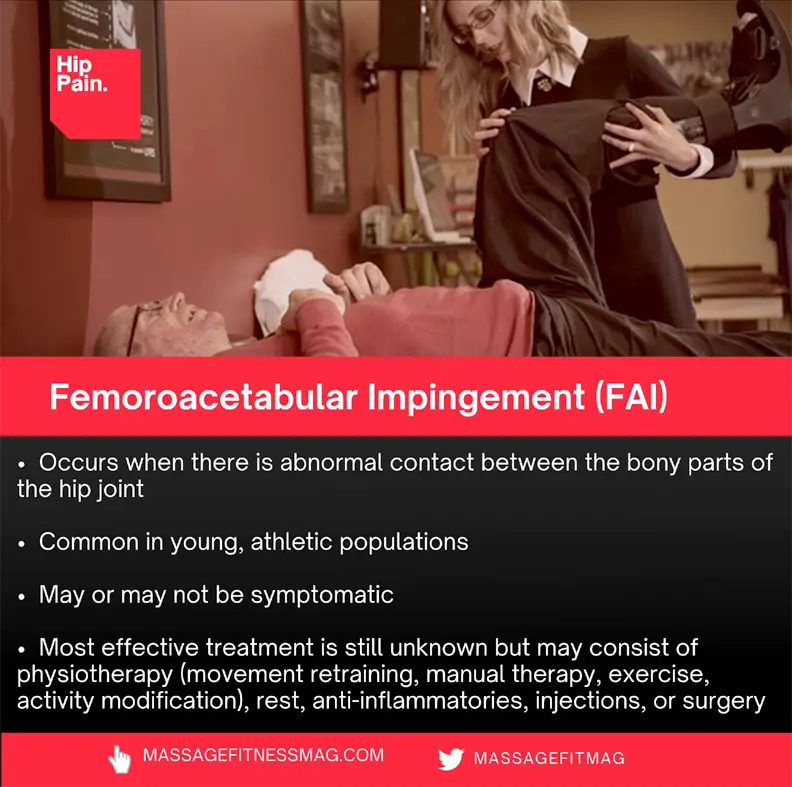

Femoroacetabular impingement syndrome occurs when there is abnormal contact between the bony parts of the hip joint. This can lead to microtrauma to the joint, damaging various joint structures, potentially leading to hip osteoarthritis. FAI is a common condition in young, active patients, but the prevalence of its various morphologies is unknown, mainly due to its propensity to present without symptoms.

Morphologic features (or types) of FAI can be seen in 23 percent to 65 percent of people without hip pain, depending on the population being studied. One systematic review estimates the prevalence of CAM deformity (a type of FAI) to be between 5 percent and 75 percent of the population in various countries, including the U.S., the Netherlands, Japan, Turkey, Canada, and South Korea.

While FAI can lead to hip pain, functional limitations, and osteoarthritis, not all people with features of FAI are symptomatic. Therefore, in addition to imaging tests, it is essential for clinicians to perform a thorough medical history and clinical examination to determine the correct diagnosis for a patient presenting with suspected FAI.

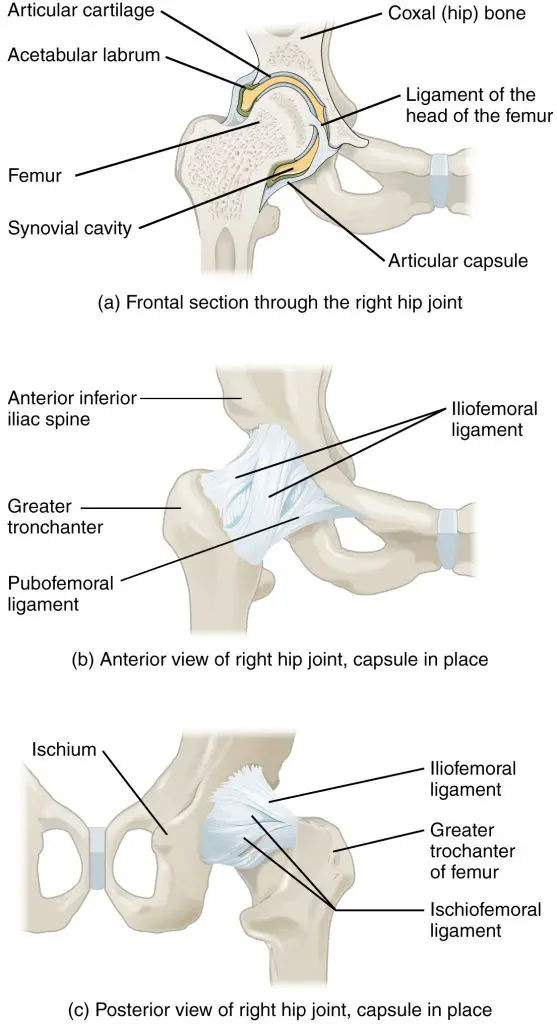

Anatomy of the hip joint

To understand the morphologic features of FAI, clinicians and patients must appreciate the anatomy associated with the hip joint.

The hip is classified as a ball-and-socket joint and is composed of the spherical head of the femur and the deep socket of the acetabulum of the pelvis.

Image: OpenStax College – Anatomy & Physiology, Connexions Web site. http://cnx.org/content/col11496/1.6/, Jun 19, 2013

The acetabular labrum is a type of cartilage that surrounds the outer edge of the acetabulum. It helps stabilize the femoral head by “gripping and sealing” it into the acetabulum, thereby creating a suction that resists distraction of the joint surfaces. It lubricates and dissipates load across the articular cartilage of the hip joint, thereby protecting cartilage from damage. People with symptomatic FAI have increased risk of damaging this structure, a suspected reason people with FAI are more likely to develop hip osteoarthritis.

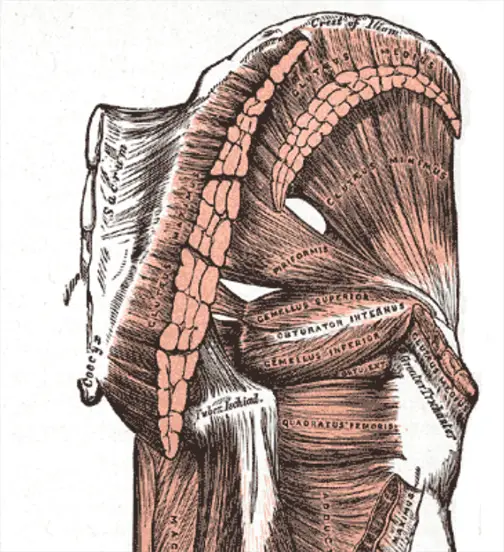

The femoral head is stabilized and sealed into the acetabulum by various connective tissues and ligaments. Ligaments determine the joint flexibility while muscles promote movement. There are 27 muscles that cross the hip joint. Innervation of the anterior and posterior hip are provided by the lumbar plexus and sacral plexus, respectively.

The gluteus medius and the hip internal and external rotators serve as the primary muscles for dynamic stabilization.

The iliopsoas serve as the primary hip flexor and stabilize the femoral head, while the gluteus maximus serves as the most powerful hip extensor.

Image: Gray’s Anatomy

Types of femoroacetabular impingement

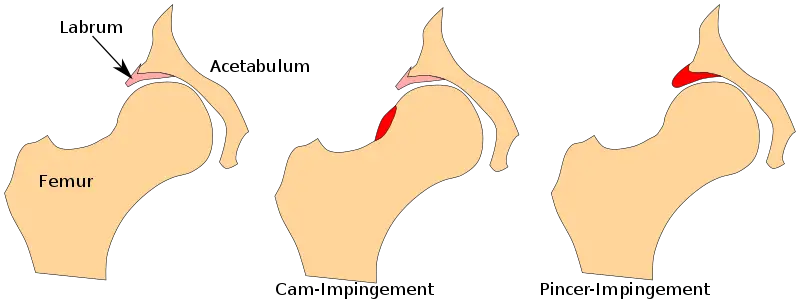

The normal skeletal anatomy of the hip minimizes biomechanical stressors between the head of the femur and the acetabular rim. When there are slight deviations in the shapes of the bones, this can compromise dynamic clearance between these two regions. Continued abutment of the femur and acetabular labrum can result in FAI, which has been a proposed mechanism for the development of early osteoarthritis. There are three main morphologies that comprise FAI.

CAM

CAM impingement occurs when bony protrusions of the femoral neck result in impingement during hip movement. Combination movements of hip flexion and internal rotation can result in shearing and compressive forces when the abnormally shaped femoral head is forced into the acetabulum. This can lead to damage to the hip joint cartilage and labrum.

CAM impingement is more common in young men (the average age of diagnosis at 32 years) who are involved in high impact sports during adolescence. History of pediatric hip diseases like slipped capital femoral epiphysis and Calve Perthes Disease are associated with increased risk for this type of FAI.

Pincer

Pincer morphology is defined as having too much coverage of the acetabulum over the femoral head. Repetitive contact between the abnormal acetabulum and the femoral head can lead to bony growths along the acetabular rim. This further increases the depth of the over-coverage and can lead to degeneration of the labrum. Unlike CAM morphology, pincer morphology is more prevalent in athletic, middle-age females, and patients typically present symptoms around age 40.

Image: – File:Femoral acetabular impingement FAI.svg.

Mixed

The final type of FAI is a combination of both CAM and pincer morphologies. Mixed morphology has characteristics of bony protrusions originating at both the acetabulum and the femoral neck. This is the most common type of morphology in people diagnosed with symptomatic FAI.

Femoroacetabular impingement symptoms

Anterior hip or groin pain and/or lateral hip pain is the most common symptom in people with femoroacetabular impingement. Typically, people with FAI describe pain as an achy or sharp, aggravated by prolonged sitting (especially in a low chair or soft couch), putting on shoes or socks, getting in and out of a car, turning towards the affected side, walking, or running.

In the early stages of the condition, symptoms are intermittent and exacerbated with activities like athletics and prolonged walking. In the mid to late stages, pain becomes more constant. Popping, locking, or snapping of the hip is another common symptom. Oftentimes, FAI can mimic other types of hip pain and is often misdiagnosed.

On examination, clinicians may find significant loss of hip flexibility, specifically in the direction of hip flexion ( less than 105 degrees), internal rotation ( less than 20 degrees), and adduction.

The FADIR test is considered positive for FAI when groin pain is reported when performed. This test is performed when the client is laying on their back and the clinician flexes, internally rotates and adducts the hip, approximating the joint and increasing shear forces to the hip labrum.

People with FAI may present with decreased hip extension, increased hip drop or a limping gait when walking. They will also demonstrate weakness in various stabilizing muscles of the hip, including hip abductors, internal rotators, external rotators, and hip flexors.

See Hip Flexor Pain: Causes, Treatments, and Evidence for a different types of anterior hip pain.

What are the causes and the risk factors of femoroacetabular impingement?

The causes of FAI are still not fully understood. Studies have illuminated some common contributors that may increase the risk for developing FAI. These risk factors include high impact athletic activities during growth and adolescence, pediatric hip disease, genetics, bony structure, impaired lumbopelvic biomechanics, and gender.

Diagnosis of femoroacetabular impingement

In order to diagnose FAI, clinical and radiological features must both be present. Oftentimes, imaging findings are incidental so they must be correlated with clinical symptoms. X-rays are most useful in identifying bony abnormalities that are common in FAI.

Physicians examine certain angles of the femur and acetabulum to determine if pincer, CAM, or mixed morphology is present. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used to assess the soft tissues around the joint, and MRA (magnetic resonance angiography) detects changes within the hip joint.

Femoroacetabular impingement treatment

Treatment for FAI can be divided into two categories: conservative and surgical intervention. Surgical intervention for FAI has become more common, demonstrating an 18-fold increase from 1999 to 2009 in the U.S. Evidence regarding surgical intervention seems favorable in the short-term for improved function and pain, but long-term outcomes are still relatively unknown.

The evidence examining conservative treatment continues to be sparse; few studies exist comparing conservative interventions like physiotherapy and exercise to surgical interventions. Therefore, many systematic reviews and meta-analyses examining interventions for FAI encourage ongoing research to determine the best treatment options.

Conservative management for FAI consists of rest, movement retraining, activity modification, physiotherapy, manual therapy, exercise, and anti-inflammatories and intra-articular injections. Effectiveness for these interventions is mixed, likely due to the limited evidence available.

Movement retraining consists of improving dynamic stabilization of the hip joint and has shown improvement in function and pain in people with FAI. However, when compared to strength and flexibility programs, there seems to be no differences in outcomes for people with FAI. This indicates that both treatments may be effective in improving pain and physical function.

Education on activity modification has also been shown to improve pain and physical function in people with FAI. Education should consist of counseling patients on joint protection strategies to avoid painful and provocative positions, including refraining from end range hip flexion and internal rotation and sitting in low soft chairs.

Gait analysis and assessment of functional activities like sitting postures, transfers, stair climbing, and sleeping postures can also help patients avoid provocative positions which may contribute to progression of FAI.

Manual therapy techniques such as soft tissue mobilization and joint mobilization and manipulation can improve capsular flexibility and range of motion. Stretching exercises focused on muscles such as the iliopsoas, rectus femoris, hamstrings, tensor fascia lata, and iliotibial band can also be useful in improving hip range of motion. Finally, there is mixed evidence supporting the use of anti-inflammatories and intra-articular hip injections in the treatment of FAI.

Surgical management for FAI involves restoring femoral head-neck alignment within the acetabulum in order to improve mobility, function, and pain, and to decrease risk of joint degeneration and development of hip osteoarthritis.

While it is too early to tell if surgical intervention is the best option for FAI, the results for arthroscopic surgery are promising, especially if hip osteoarthritis is absent. If pain or function is not improved with conservative treatments, surgical intervention is considered the next step in management.

Types of surgery include hip arthroscopy or open procedure with options for labral tear resection/repair, capsular modification and/or osteoplasty. Hip arthroscopic surgery is preferred due to fewer complications, faster recovery time and improved function compared to open procedures.

Systematic reviews have tried to identify the best candidates for hip arthroscopy in order to optimize recovery. Patients who are younger males with a low body mass index have better outcomes post-surgery compared to patients who are over 45 years of age, female sex, and classified as overweight or obese.

Pain lasting greater than eight months also predicts less favorable outcomes of the surgery. Radiographic characteristics predictive of good surgical outcomes include lack of arthritis on imaging, increased joint space between the femur and acetabulum, and pain relief from pre-operative intra-articular hip injections. Patients who undergo labral repair have an increased chance of positive outcomes compared to those who underwent labral debridement.

If considering treatment for femoroacetabular impingement, you should consult your physician or other qualified medical professional to determine the best intervention for your condition.

What should massage therapists consider when treating a client or patient with femoroacetabular impingement?

When assessing a patient with FAI, massage therapists should assess hip range of motion, muscle flexibility, and take a detailed history about positions and postures that provoke groin pain symptoms. During the treatment, avoid performing soft tissue work with the hip in end range flexion and internal rotation.

Soft tissue work and manual stretching should target the iliopsoas, rectus femoris, hamstrings tensor fascia lata, and iliotibial band. The clinician may counsel patients on joint protection strategies to avoid provocative positions, such as refraining from sitting in low soft chairs, crossing the legs and sleeping in the fetal position. Massage therapists should consider referring clients with suspected FAI to a physiotherapist for further conservative treatment.

When my friend Davor presented his findings on risk factors for femoroacetabular impingement back in 2012, much of the information was novel. We still have a lot to learn about FAI. Though research in this area is increasing, the most effective treatments and underlying mechanisms for FAI are poorly understood.

My time performing research has taught me that scientific understanding is ever evolving. There may always be conflicting evidence, but as we inch towards a consensus, we will become better equipped to prevent progression and disability related to this common condition.

What Is Gluteal Tendinopathy? Sometimes its symptoms can overlap with FAI.

Follow Dr. Weyrauch on Twitter: @TheSteph21 and her podcast at Healthcare Education Transformation.

Stephanie Weyrauch, DPT

Dr. Stephanie Weyrauch is employed as a physical therapist at Physical Therapy and Sports Medicine Centers in Orange, Connecticut. She received her Doctorate in Physical Therapy and Master of Science in Clinical Investigation from Washington University in St. Louis. She has served on multiple national task forces for the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) and actively lobbies for healthcare policy issues at the local, state, and national levels of government.

Currently, she serves as Vice President of the American Physical Therapy Association Connecticut Chapter and is a member of the American Congress for Rehabilitation Medicine.

Dr. Weyrauch is also the co-host for The Healthcare Education Transformation Podcast, which focuses on innovations in healthcare education and delivery.

She has performed scientific research through grants from the National Institutes of Health and National Science Foundation at world-renowned institutions including Stanford University and Washington University in St. Louis. Her research examining movement patterns and outcomes in people with and without low back pain has led to numerous local, regional, and national presentations and a peer-reviewed publication in Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, a top journal in rehabilitation.