Upper cross syndrome refers to the hunched posture of the upper body, particularly in the shoulder girdle, neck and head, and upper spine. Certain upper body muscles are considered “tight” and “weak,” which may cause less flexibility in the shoulders, discomfort, and pain.

A client I see regularly for massage therapy fits many of the telltale signs associated with upper cross syndrome. They work primarily in front of a computer, sitting at a desk for long hours.

Their posture is hunched, and their shoulders are rounded forward, causing their chest to look almost concave. When they come in to see me, the usual complaint is rhomboid pain, pain in the upper back and shoulders, and sometimes a headache that starts in the neck and goes into the jaw.

We tend to attribute pain to posture, however, research into the experience of pain reveals a more complex relationship than just posture.

Janda’s upper cross syndrome

The term “upper cross syndrome” was coined in 1978 by Dr. Vladimir Janda, a twentieth century Czech neurologist, professor, and researcher. Janda was a pioneer in the fields of manual therapy and rehabilitation, championing the blend of anatomy and movement in clinical work, known as functional anatomy.

His work suggested that issues of joints, the musculoskeletal system, and the nervous system would affect the way other parts of the body functioned both locally and systemically.

He presented the idea of several “crossed syndromes,” including lower crossed syndrome and layer syndrome. These “postural syndromes” he described as musculoskeletal imbalances centralized around the shoulder girdle and the pelvic girdle.

The hallmark of these postural deviations is overactivity in some areas and under activity in the opposing muscles. As the conflict between joint and muscle forces continues, the condition can worsen towards injury.

There are also various types of postures that are associated with upper cross syndrome:

- Kyphosis

- Forward head (“text neck”)

- Hyperkyphosis or dowager’s hump

Just as upper crossed syndrome affects the upper body, lower crossed syndrome follows a similar path of opposing weak and tight muscles in the lower body. Layer syndrome affects both the upper and lower portions of the body as a combination of the upper and lower cross syndromes.

In some cases, upper cross and lower cross syndrome may affect each other.

Upper cross syndrome causes and symptoms

The imbalance displayed by upper cross syndrome expresses itself in the neck and shoulder area. (Photo by Halley Moore)

The imbalance displayed by upper cross syndrome expresses itself in the neck and shoulder area.

“Tight” muscles that can be overactive include:

- upper trapezius

- levator scapulae

- sternocleidomastoid

- pectoral major and minor

“Weak” muscles that are considered underactive include:

- deep cervical flexors

- lower trapezius rhomboids

- serratus anterior

Other types of posture that often goes along with upper cross syndrome include

- forward head posture

- rounded shoulders

- winged scapulae

- too much curvature of the thoracic spine (kyphosis).

These lines of tension create an “X” pattern and put stress on the joints of the neck and shoulder.

Upper cross syndrome can manifest with back pain, neck pain, shoulder pain, jaw pain, or headaches, which can cause sensations of tightness across the chest, shoulders, and neck, even compromising movement in the upper body.

For many people, the hunched shoulders and forward head posture have the added negative effect of being considered less desirable in appearance.

Does upper cross syndrome cause pain?

Upper cross syndrome features rounded shoulders, forward head, and a concave chest. (Photo by Nick Ng.)

While many manual therapists are still taught that abnormal movements and posture strongly related to pain, the last several decades of pain research have encouraged a shift away from this viewpoint. Janda partially attributed the issue of upper crossed syndrome to maintaining a slouched position while sitting. In particular, the link between posture, pain, and dysfunction seem to be quite weak.

For example, in 2009, Australian researchers from the School of Physiotherapy at the Curtin University of Technology conducted a cross-sectional study of more than 1,500 teenagers to investigate the relationship between sitting posture and physical, psychological, and social factors.

They found that the relationship between back pain and posture was quite complex and heavily influenced by other psychosocial factors like negative thoughts and self image, gender, body mass index, and activity.

The same study did find some evidence that more upright postures could still have positive impacts on quality of life, like emotional state, motivation, productivity, and in some cases back pain. Ultimately, however, it was concluded that the correlation between sitting posture and back pain was weak, and that the upright posture was not something that could be said to be a fit for every person.

In another study from Curtin University, researchers focused on neck posture while sitting. They gathered data by measuring the angle of subjects’ neck posture through photographs, and information about subjects’ pain level and lifestyle factors through questionnaires.

They found similar results that factors like exercise, mental state, and body mass index were stronger influences of neck pain and headaches rather than sitting posture.

As you can see, the case for posture directly correlating with pain and dysfunction is weak. The influence of biological, psychological, and social factors on the pain experience shows it to be much more complex than singularly connected to cross syndromes.

Despite the evidence, Dr. Janda’s work continues to influence manual therapy where many therapists aren’t taught up-to-date information about how pain works.

Do upper cross syndrome treatments work?

Treatment options for upper cross syndrome include physical therapy, massage therapy, pain education, and exercise. While there’s no quick fix or “cure” for the posture, a combination of these treatments can provide the most promise of symptomatic relief.

To date, there aren’t many high-quality studies or reviews that examine what are the best treatments for upper cross syndrome. So, we can only work with what we have to make the best decisions.

Physical therapy

A physical therapist may combine stretching, range of motion and strengthening exercises, manual therapy, and pain education to reduce your symptoms.

However, there’s scant evidence that shows whether physical therapy works or not.

Current studies are based on small sample populations that may not be applied for the general population. For example, a 2020 physical therapy study found that a corrective exercise program for eight weeks could improve “muscle activation imbalance, movement patterns, and alignment” of the shoulder girdle and neck, and these effects were maintained for four weeks after the treatment among 24 college-age men.

Likewise, another study in Pakistan of 60 men found that adding “soft tissue manipulation” with a scraping tool (IASTM) and some stretching was “more effective” in managing neck pain from upper cross syndrome than standard physical therapy, such as using hot packs, electrical stimulation, and stretching.

So there’s no consensus on what type of treatment of physical therapy actually works, but it’s likely that having quality touch and social and empathetic support (from the therapist!) can bring comfort and more certainty about your outcomes.

Massage therapy

Massage therapy can use soft tissue manipulation, assisted stretching, and even heat therapy to bring pain relief for upper cross syndrome.

Since all types of massage involve touching your skin, it stimulates sensory organs in your skin that promotes relaxation. And so, massage can help decrease stress levels in your brain, increase patient resilience, and stimulate the parasympathetic nervous system to calm you down.

[Related: Descending Modulation: Why Massage Therapy Can Alleviate Pain]

Ergonomics

Ergonomics focuses on both your body and your surrounding environment. Ergonomic adjustments can be made when workplace conditions contribute to upper back, neck, and shoulder pain. where workers are often in fixed positions, engaging in repetitive movements (e.g. factory, desk jobs, bus drivers).

But does it help? Maybe.

In 2019, researchers in Hong Kong found a blend of educating participants on proper workspace layout and ergonomic risks, applying the ergonomic improvements, and adding in physical exercises was helpful in relieving work-related neck and shoulder pain.

While both the ergonomics group and the control group had reduce neck and shoulder pain, the ergonomics group reported their work environment to be less physically-demanding than the other group.

It was limited, however, in designing protocols that would fit work environments outside of an office and applied outside of a controlled research setting.

Overall, engaging the participant in their treatment, encouraging movement, and stimulating sensory awareness seem to have positive effects for treating upper cross syndrome. But the evidence doesn’t favor any specific methods of treatment, and is often limited by sample size, study duration, and repeatability.

Upper cross syndrome exercises

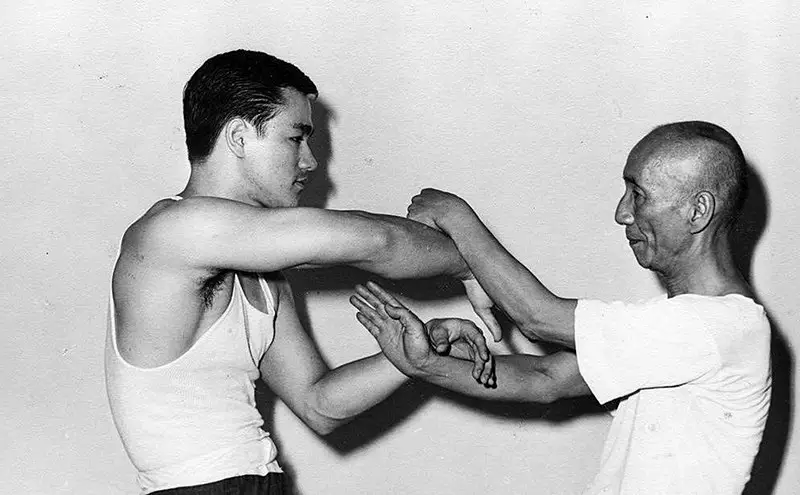

Bruce Lee and Grandmaster Ip Man practicing Wing Chun sticky hands in “upper cross syndrome” posture.

(Photo: Uploaded by שילוני on Wiki Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lee_and_yip_chi_sau.jpg)

Corrective exercise is a common intervention for upper cross syndrome, focusing on fixing deviations from a neutral posture. However, there’s not a large body of data to support the efficacy of exercises that specifically target upper cross syndrome. The idea of correcting posture rarely takes into account of natural variations in body structure.

But if you want to try some exercises to alleviate the tight feeling in your chest, neck, and shoulders, try the following:

Neck rolls

Shoulder rolls

Doorway chest stretch

Do exercises for upper cross syndrome work?

One reason why some people think exercise works is because it can give you an analgesic effect by releasing endorphins in your brain.

But for some people with chronic pain, exercise can also stimulate a negative response, like pain flare-ups. And so, any approach should be modified and tailored to you.

Generally, positive effects of strengthening and stretching exercises are demonstrated by a few sources.

For example, abducted or “winged” shoulder blades is a common feature of upper cross syndrome, and some researchers find that stretching shoulder abductors (e.g. trapezius, serratus anterior) for 30 seconds may be better in reducing the hunching posture than strengthening the shoulder retractors (e.g. rhomboids).

Like most related research, there’s a shortage of such research to confirm what really works or not. But what’s known is that shoulder position doesn’t affect much on shoulder muscle strength.

The researchers also noted that any improvements from these exercises may be offset returning to normal activity. So it’s difficult to rely on results gained in a fully controlled setting when there are so many variables involved in the daily mechanics of life.

In 2016, researchers in South Korea studied strengthening and stretching the trapezius and levator scapulae. They found a positive impact on structural symptoms of upper crossed syndrome but couldn’t determine if they participants had any pain reduction because that question wasn’t included in the study.

Exercise as a whole is a generally positive way to impact pain and discomfort in the body, without much evidence for “fixing” postural deviations. So taking breaks from sedentary, immobile positions and moving your body in various ways can reduce discomfort and pain.

Final thoughts

As a massage therapist in the U.S., I do not provide a diagnosis. However, it’s easy to start noticing patterns in the human body and wanting to assign a name to them internally. I prefer to engage with my clients by talking about the sensations they’re experiencing and use that as the model for a treatment—rather than being the one to determine what needs to be “fixed” in them.

There are so many variations of what is “normal” in every person, and it’s rare to find someone that matches a textbook normal out in the world.

I’ve had great success with the client I mentioned by approaching the symptoms that cause them discomfort without pathologizing them. Slow, gentle interventions that give them the time to reconnect with their nervous system, and letting their feedback inform the process.

Sometimes trying to move the shoulder back feels good, and sometimes it triggers pain and resistance in their neck and jaw that needs to be eased back. A soft hand, a warm pillow, and a check in can get it back on track.

I have not noticed a big postural change in getting their shoulders down and back, but we have made great progress in lessening the back pain and the headaches, which leads me to agree with the current supposition that the posture and pain need not be interconnected.

Halley Moore, LMT

Halley E. Moore is a private practice licensed massage therapist, freelance writer, and small business consultant (Calliope Insights) in St. Louis, MO. Her diverse array of educational credits include a B.S. in Business, a massage therapy certification from The Healing Arts Center in St. Louis, various training in trauma-informed care, current enrollment in a web development coding course, and a dream of a private investigator’s license.

Halley first discovered an interest in anatomy by hanging upside-down from a trapeze as an aerial artist. Everyday after practice, new bits of her body hurt, so she figured it might be worth learning their names.