A Baker’s cyst, or a popliteal cyst, is the inflammation of a bursa in the back of the knee. This is often caused by rapid accumulation of the fluids in the bursa, which may lead to inflammation from constant rubbing of the muscles and tendons during movement.

While this is more common among adults with a history of knee or leg trauma, a Baker’s cyst can develop with other joint diseases and disorders, such as arthritis and meniscus tears.

Posterior knee anatomy

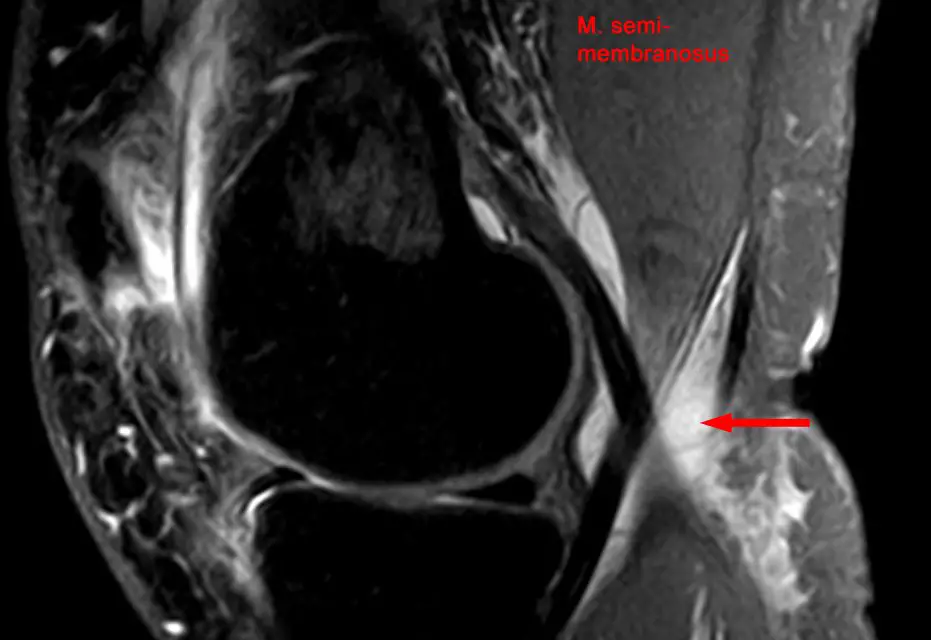

The knee has several types of bursae that reduce friction between the bones, muscles, and tendons during movement. The Baker’s cyst comes from one of these, which is called the gastrocnemius-semimembranosus bursa, which is located between the medial condyle of the femur, the semimembranosus tendon, and the medial head of the gastrocnemius, slightly below the popliteal fossa.

Baker’s cyst causes

The gastrocnemius-semimembranosus bursa is a primary cause of Baker’s cyst. Because the bursa has an opening that allows synovial fluid to flow into it in a one-way direction, this flow tends to increase among older people because the joint capsule loses its elasticity with age.

Accumulation of fluids builds up pressure that may eventually rupture through the thin membrane that separates the bursa from surrounding tissues. Even if the bursa does not rupture, the enlargement can cause restriction of knee flexion and extension, joint stiffness, and even pain behind the knee. However, small Baker’s cysts may likely be asymptomatic.

Other causes may be:

- Injury or trauma to the knee

- Torn cartilage in the knee

- Arthritis, particularly rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis

- Infection in the knee that causes fluid buildup

- Underlying knee joint problems like meniscus tears, chondral lesions, and ligament tears

How common are Baker’s Cysts?

Several studies found that the prevalence of Baker’s cyst varies among different populations. Children and adults alike could get this condition.

One German study in 1999 found that among 168 asymptomatic children ages 14 and under, only 2.4% of them—four patients—had a Baker’s cyst. In 2011, a group of German researchers followed 80 children in which 55 of them had a Baker’s cyst, over five consecutive years. At the end of the study, 29% of them had symptoms and complications from the cyst, and knee pain was reported among 56% of the children.

Other countries reported as follows:

- An Egyptian study in 2017 found that nearly 13% of more than 1,500 women between ages 46 and 68 had a Baker’s cyst. Those who are more at risk are those who have knee osteoarthritis, are obese, have large effusion, or had several cartilage removed in at the femur.

- A 2002 German study found that 20 out of 100 patients who had both a Baker’s cyst also had larger medial meniscus tears and higher knee cartilage degradation.

- A 2012 study in Taiwan found that 28 out of 103 patients with gouty arthritis at the knee also had a Baker’s cyst, but only 10 of these were diagnosed.

Baker’s cyst symptoms

Symptoms of a Baker’s cyst include

- Swelling and achy pain behind the knee, which often is more painful when the knee is fully extended

- Limited knee flexion because of large swelling

- Swelling of the calf (edema)

- Symptoms may be similar to deep vein thrombosis and thrombophlebitis

Baker’s cyst treatment

Both surgical and non-surgical treatments have some success in not only reducing the symptoms of Baker’s cyst, but also removing the cyst without compromising knee function and general health.

A 2020 systematic review of 30 qualified studies (9 non-surgical) investigated two primary treatments: corticosteroid injection and surgery.

Corticosteroid injection

Corticosteroid injections, administered either directly into the cyst or into the knee joint, may reduce the size of a Baker’s cyst, as well as decrease pain and disability associated with the cyst.

In the review, eight out of nine studies used corticosteroid injection to the cyst, and one study used radiation therapy. Among the injection studies, all but one also used another type of treatment, such as aspiration (draining of the cyst fluid) and electrical therapy.

Despite the mixed results of these studies, the authors of the systematic review still favor conservative treatment instead of surgery. Ultrasound imaging of the popliteal cyst should be used to predict how a patient would respond to a treatment.

However, cysts with a thick coating may be resistant to injection treatments. They suggested that creating an opening of the cyst (fenestration) to drain the fluid first would have better outcomes.

Surgery

Open surgery has been shown in the review to be successful in removing the cyst with few complications, but it doesn’t address the underlying knee pathology that caused the cyst to manifest. One study in the review showed that patients who undergo open surgery are 7.5 times more likely for the cyst to reform than those who had open surgery and treatment of the underlying knee problem.

In some cases, treating the actual problem, such as meniscus tears with symptomatic Baker’s cyst, can resolve the cyst problem without even touching it. However, the systematic review’s researchers warned that patients with high-grade osteoarthritis may need more surgery to resolve the cyst problem because of persistent joint effusion.

Thus, the authors suggested that a combination of open and arthroscopic surgery should be used, depending on the patients’ condition. However, they warned that open surgery alone shows “no clear demonstration of superior outcomes.”

With the lack of randomized controlled trials and sufficient prospective studies, there are no standard guidelines for clinicians on the best way to diagnose and treat a Baker’s cyst.

Baker’s cyst name origin

While the name Baker’s cyst is named after British physician William Morrant Baker, it was another physician, Robert Adams, who first described the bursa in 1840, including the valve that moderates the fluid flow.

Blome et al. described the findings of French physician E. Foucher in the mid-1850s how the bursa becomes firm when the knee is extended and gets softer when the knee is flexed. During knee flexion, the valve is opened to allow fluid to flow from the cyst to the joint, while during knee extension, the valve is blocked and fluid stays in the cyst.

By the 1870s, after Baker became the Warden of the College of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in 1867, his subsequent research on the popliteal cyst became more well-known, and the condition was named after him.

In his obituary in The British Medical Journal in 1896, he was described as a more proficient writer than a physiologist, being able to “use his pen and editorial talents for educational purposes. Baker was so respected by his peers and students that they nicknamed a popular physiology textbook at the time (Kirkes’ Handbook of Physiology) “Baker’s book.”

Although Baker was well-known for his studies on the popliteal cyst, he also had contributed to the studies of anthrax, whitlow, and ranula.

Baker’s cysts and massage therapy

Patients or clients with Baker’s cyst should be taken with extra caution, whether they have symptoms or not.

“Cysts do not have to be symptomatic. So a finding—whether from a PT, MD, MT—isn’t indicative of the cyst being a pain generator,” physical therapist and licensed massage therapist Bill Jones said, owner of Jonesercise in Columbus, Georgia. “If a cyst was ‘symptomatic,’ I wouldn’t advise direct treatment to the cyst but more indirect around, above, and below the area as there may be muscular tension or splinting around the cyst area.”

Aside from manual therapy techniques, Jones emphasized that communication skills are another important part of the treatment that some therapists overlook.

“About 95% of the folks I see have had symptoms for years, have had multiple physical therapy treatments, been told different things by different practitioners,” Jones said. “Essentially, I start out by speaking with them. The first thing, for me, is not having any preconceived notions about the person I’m about to see. It takes a lot of practice to let go of any bias I might have and is a continued effort but a worthwhile effort.”

For Jones, listening to his patients is a huge part of what he does. He may pick up something from his patients’ narrative that previous practitioners may have missed. So in terms of dealing with pain behind the knee or other joint and muscle pain, the listening part can be just as beneficial as the hands-on work.

“Their stories are real. What they feel is real. Their descriptions are real,” Jones said. “And trying to get any change at all has to come from respecting their stories,” Jones said.

Further reading

Massage and Joint Pain: a Biopsychosocial Approach

How Massage Can Help Treat Chronic Pain

What Is Pain and Why Do We Feel It?

A native of San Diego for nearly 40 years, Nick Ng is an editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine, an online publication for manual therapists and the public who want to explore the science behind touch, pain, and exercise, and how to apply that in their hands-on practice or daily lives.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a B.A. in Graphic Communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014.

When he is not writing or reading, you would likely find him weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, or exploring new areas to walk and eat around Southern California.