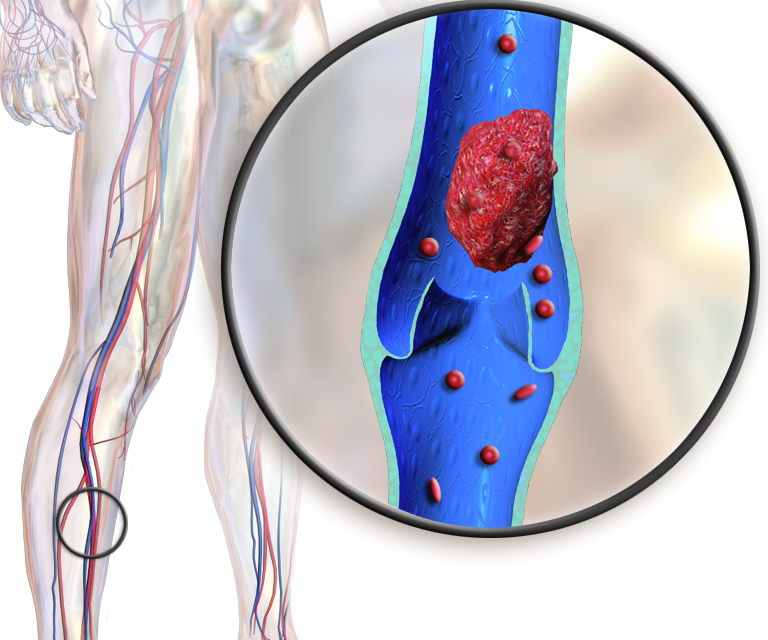

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is where a blood clot forms in a vein that is deep in your body, and sometimes, its symptoms can be felt in behind your knee when the clot is formed or forming in the popliteal vein. This can be fatal if the clot breaks off and travels to the heart or lungs, which can cause pulmonary embolism.

This is what had happened to NBC war journalist David Bloom, 39, who died from DVT in April 2003 when he was covering the Iraq War in Iraq. His wife, Melanie, raised national awareness to DVT since then, including features on Larry King Live and Oprah. (Personally, my own high school creative writing teacher, Mr. Gary Bradshaw of Rancho Bernardo High, died from a similar condition during the Christmas season of 1994.)

Also known as thromboembolism, deep vein thrombosis can be a quick and silent killer like a heart attack if the symptoms are ignored or not as obviously noticed. This article focuses mostly on DVT of the leg.

Massage therapy and deep vein thrombosis

Massage therapy is generally not recommended for people with DVT, according to research. A recent case report from Chiang Mai University in Thailand documented a 25-year-old pregnant woman who had dyspnea (difficulty in breathing) and lapsed in and out of consciousness after receiving a five- to ten-minute foot and lower leg massage that often is used initially during a traditional Thai massage.

She later had seizures, became unconscious and had cardiac arrest. After her life was saved by first responders and was sent to a local hospital, clinicians found that she had pulmonary embolism that stems from a blood clot in the lower leg, which was undetected until the fatal symptoms occurred.

The authors suggested that pregnant women should “avoid leg massage unless they are certain that no thromboembolism disorders exist.”

Another case of DVT (specifically VTE) with deep tissue massage was reported where a 67-year-old California man with no known risk factors had a “vigorous deep tissue massage.”

In 2010, the man went to the emergency care and had pain in his upper right chest, but he was discharged because radiographs and health history intake show no obvious signs of cardiovascular disease. His case was ruled to be musculoskeletal in nature and was asked to return in five days if the symptoms did not improve.

Well, the man’s symptoms did not improve. The pain worsened, especially during any physical exertion. He went to see his primary care physician five days after the ER visit. The doctor asked him more questions about what the man did before he went to the ER, and it turned out that he had a “vigorous deep tissue massage” on his right calf for non-medical reasons. The swelling and pain in the calf began the day after the massage. Five days after the calf symptoms subsided, the chest pain began. He was given anticoagulant therapy with four days of hospitalization and was discharged in stable condition.

Thrombosis vs embolism

A thrombosis is a blood clot that is formed in a vein or artery. Embolism refers to a stuck blood vessel which blocks blood flow, while an embolus refers to a piece of blood clot or a similar object. Therefore, not all thrombosis becomes embolism (but it’s a significant risk factor) and not all embolism is thrombosis.

In DVT, this refers to a blood clot behind the knee in the popliteal vein and femoral vein.

Symptoms

DVT in the back of the knee is the most common type of venous thrombosis and about half of the people who have DVT do not have any symptoms.

Symptoms of DVT include:

- inflammation of the blood vessel

- Swelling of the knee, ankle, and/or foot

- Pain behind the knee

- Muscle cramp in the calf of the affected leg

- Tenderness in the back of the knee or lower leg

- Reddish or bluish skin in the affected area

- Skin feels a lot warmer than nearby skin

For those who have asymptomatic DVT, they may know they have it until the blood clot reaches one of the lungs, which is called pulmonary embolism. This can be fatal and they would need emergency care.

Other symptoms may be similar to a heart attack, such as:

- Chest pain

- Discomfort that worsens with coughing or deep breathing

- Troubled breathing

- Irregular heartbeat

- Very low blood pressure—particularly in a systolic reading

Causes

Various risk factors contribute to developing a blood clot in the leg. These include:

- Reduced blood flow due to lack of movement (e.g. bed rest, sedentary lifestyle, injury to the vein from physical trauma, surgery, venous previous DVT, drug abuse via injections)

- Increase venous pressure, due to pregnancy, stenosis, and other factors)

- Increased blood thickness

- Genetics

- Diabetes

- Smoking

- Chemotherapy

- Sepsis

Even anatomical variations of the lower limb’s venous system can affect the likelihood of getting DVT. Several researchers in Qatar gathered data from 637 hospital patients with DVT from 2008 to 2012, and they found that pulmonary embolism from DVT is more common in the left lower leg than the right one.

Those with DVT on both legs are more likely to get it again, as well as pulmonary embolism and higher mortality. Also, patients with DVT closer to the hip have a higher mortality rate than those with DVT toward the lower leg. Some patients in the sample have more than one site of blood clots.

They also found that obesity is another risk factor of getting DVT because of increased compression of the veins in the upper and lower legs. Two common areas where DVT occurs are where the vein bends with the joint, such as the knee and groin. These areas include:

- Popliteal vein (74%)

- Profunda femoral vein (74%)

- Common femoral vein (50.4%).

Mortality from DVT is quite high. A 2019 narrative review of DVT states that about 6% of patients with DVT will likely die within 30 days, mostly from pulmonary embolism. That percentage increases to 13% if the patients are diagnosed with pulmonary embolism.

Even if treatment is successful, about 20% to 50% of these patients would develop post-thrombotic syndrome, a condition where there is damage to the valves in the veins due to DVT. About 3% of these patients get chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (high blood pressure in the lung’s arteries), and there is a 40% recurrence of lower body DVT within 10 years after three to six months of anticoagulation treatment.

Another study of more than 5,000 patients in Beijing, China, found that patients with respiratory diseases, elderly patients in long-term care in general, and those with “internal medicine” diseases are more likely to develop DVT than those with physical trauma, surgery for bone fractures, or other types of invasive procedures.

Treatments

Treatments for DVT minimize the risk of getting another blood clot, pulmonary embolism, and similar conditions. Because every patient with DVT has a unique health history, beliefs about treatments and their own health, and other biopsychosocial factors, there are no cookie-cutter approaches to DVT treatments.

Anticoagulants

Because viscous blood increases the risk of developing a blood clot, anticoagulants may be used to treat DVT and its related conditions. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) suggests that anticoagulants should be used for those with proximal DVT (toward the hip) rather than distal DVT (toward and below the knee).

The guidelines also consider the risks vs. benefits of taking anticoagulants because the treatment may likely cause more harm to certain people than benefits. For example, the American College of Chest Physicians recommends that patients with a symptomatic blood clot in the hepatic vein should get anticoagulant therapy, while those who had such “incidentally detected” cases should not get such therapy. Still, the college suggests that clinicians should consider individual differences (e.g. diabetes, obesity, lifestyle) and preference of treatments.

There is some evidence that suggests treatment duration and the type of DVT may affect the outcome. A 2020 Cochrane Review of eight randomized controlled trials with a total of more than 1,200 subjects found that anticoagulant therapy with vitamin K had “little to no difference in major bleeding events.” However, the amount of bleeding was clinically significant compared to the control groups that had no intervention or a placebo. In other words, the results showed a tiny effect that appears to have little to no impact, but among those patients with bleeding, it may likely warrant clinicians to use extra caution when recommending anticoagulants.

Five of the trials in the Cochrane Review compared patients with anticoagulation treatments for up to three months and those without anticoagulation, while the other three trials compared anticoagulation treatments with different time frames. While the treatment shows a significantly greater reduction of risk of getting VTE again, there is “no clear effect on the risk” of getting a pulmonary embolism recurrence.

Three months of anticoagulant treatments was shown to be better than shorter treatments that last up to six weeks in reducing the risk of getting VTE again. However, all trials show “no clear difference” in all types of bleedings.

Thrombolysis

Thrombolysis is the removal of a blood clot from a blood vessel by using medications that dissolve the clot. A catheter is inserted into the vein in a process called percutaneous coronary intervention to deliver the meds.

The NICE guidelines suggest that such therapy should be used for those with symptomatic DVT in the iliofemoral vein that lasts less than 14 days, have a life expectancy of one year or more, fairly functioning in daily activities, and have a low risk of bleeding.

However, there is not much high-quality evidence that shows thrombolysis for lower limb DVT is safer in terms of risk of bleeding versus other types of treatment. The most recent systematic review of 45 qualified studies with 4,740 subjects found that thrombolysis increases the risk of major bleeding, including bleeding within the skull, even though the intervention can “probably reduce mortality” among patients with pulmonary embolism and post-thrombotic syndrome. The level of certainty ranks “moderate” and “low,” respectively, which measures how reliably the data are.

“Stakeholders involved in the decision making process would need to weigh these effects to define which clinical scenarios merit use of thrombolytic therapy for patients presenting with acute VTE,” the researchers concluded.

Inferior vena cava filter

The inferior vena cava filter (IVC) is an implant used to prevent blood clots from entering the lungs for patients who are at risk of repeated clots. This device is usually recommended if anticoagulants are contraindicated.

A 2011 systematic review of 37 non-randomized trials of more than 6,800 patients found that it seems to be effective for preventing pulmonary embolism, but there is a lack of consistency of such prevention in two of the studies, the authors wrote.

There is also a risk of increased incidences of DVT closer to the groin. For example, one study found that there is nearly a 21% chance of getting DVT after two years of using an IVC filter versus nearly 12% in the anticoagulation group. Eight years of usage of the IVC filter further increased the chance of getting DVT to 37% while the anticoagulant group had 27.5%.

In 2018, another systematic review of seven qualified trials found that there was “no significant difference” in mortality rate, DVT, and pulmonary embolism recurrence, or bleeding. Because of the inconsistent experimental setup, small sample sizes, and lack of randomized controlled trials, the researchers concluded that “insufficient data exist on the efficacy of retrievable IVC filters,” as well as safety concerns. However, they said that this does not mean IVC filters do not work to prevent pulmonary embolism. Like anticoagulants and thrombolytic treatments, it is mostly a matter of risks versus benefits.

Compression stockings

Compression stockings and similar compressive legwear is often used to reduce or prevent future occurrences of DVT. Although no one really knows how they work, a 2016 systematic review showed benefits and no benefits of using compression stockings for DVT.

Out of five randomized controlled trials with a total of nearly 1,400 patients, only one trial showed no benefit. Because of the limited number of studies included and the mixed methods of the experiments, the researchers “refrained from pooling the results” of the trials.

A 2018 Cochrane Review has a comprehensive investigation that covered 20 randomized controlled trials with 1,681 patients total. The researchers explored and evaluated the effectiveness and safety of compression stockings among DVT patients who were hospitalized and had different interventions, such as cardiac surgery or neurosurgery.

While the overall data finds that the stockings had decreased the number of DVT incidents, small sample sizes limit the statistical power of the meta-analyses, meaning that the results may have a good chance of being a type I error (false positive). Most of the trials used only stockings that reach mid-thigh, so there is not enough evidence to conclude what other lengths of stockings can do. Even so, the researchers broke down three levels of evidence of what compression stockings could do:

- High-quality evidence suggests that compression stockings can prevent DVT in a clinical setting, particularly among surgical patients.

- Moderate-quality evidence suggests that compression stockings may prevent DVT at the proximal level (toward the groin).

- Low-quality evidence finds that compression stockings can prevent pulmonary embolism. Only two of the five trials reported about pulmonary embolism and the results were “inconsistent.”

Exercise

Exercise may likely reduce your risk of getting deep vein thrombosis, particularly venous thromboembolism. A meta-analysis of 12 studieswith a total of 14 different observational prospective cohort studies had a total of more than 1.28 million subjects and more than 23,700 VTE cases. This type of cohort study follows a group of people over a period of time and examines a condition that cannot be done experimentally (often due to ethical reasons).

Regular exercise, such as walking and cycling, can increase blood flow in the veins, reducing the risk of getting a blood clot. The Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report recommends that adults should get between 2.5 to five hours of moderate-intensity physical activity per week or 1.5 hours to 2.5 hours of vigorous exercise per week. This can be a combination of walking, hiking, gym workouts, swimming, and social dancing.

Exercise and prevention

The evidence behind exercise for DVT prevention is limited and uncertain.

A 2019 report in DARE (Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects) finds that morning walks are generally safe and “may prevent or improve post-thrombotic syndrome.”

The authors of this review cited that short-term exercise, such as 30 minutes of walking on a treadmill, did not worsen DVT symptoms. Based on several trials in their review, there was no difference between the exercise and no exercise groups in recurrence of a blood clot.

Because most of these results are based on one or a few randomized controlled trials or observational studies with mixed methodologies, the jury is still out on what exercise can do for DVT. But based on prior knowledge about the benefits of regular exercise, it has many health benefits that should be included in the reasons why you should continue or start to exercise regularly.

But in some cases, regular physical activity may not be enough, as in the case of Mr. Bradshaw, who was pretty active and loved skiing and cycling. His lifestyle may have staved off DVT, but his skiing injury may have broken that defense, which went undetected during his treatment and recovery.

Massage therapists who work with people with deep vein thrombosis should take extra caution when doing their health history intake and applying hands-on work.

This article is not a substitution to medical advice and is for informational purposes only.

Further reading

Massage and Joint Pain: a Biopsychosocial Approach

How Massage Can Help Treat Chronic Pain

Massage Therapy and Blood Circulation

A native of San Diego for nearly 40 years, Nick Ng is an editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine, an online publication for manual therapists and the public who want to explore the science behind touch, pain, and exercise, and how to apply that in their hands-on practice or daily lives.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a B.A. in Graphic Communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014.

When he is not writing or reading, you would likely find him weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, or exploring new areas to walk and eat around Southern California.