Posterior knee pain may be caused by injuries to areas like the back corners of the knee, the lateral collateral ligament, posterior oblique ligament, or the iliotibial band (IT band). Other causes of pain behind the knee include:

- Baker’s cyst

- Hamstring strain

- PCL tear

- Vascular problems in the posterior thigh

Posterior knee anatomy

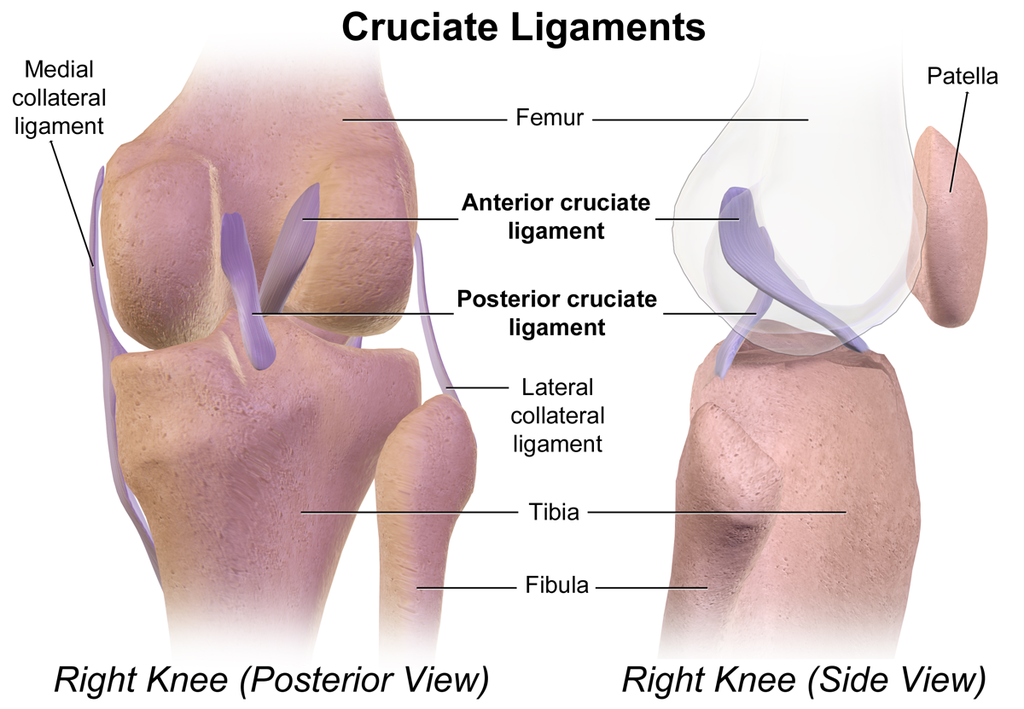

The knee acts as a specialized hinge, comprising the tibia, femur, and patella. While its main movement is bending and straightening, conditions like injury or disease can cause it to move sideways, rotate, or shift forward and backward.

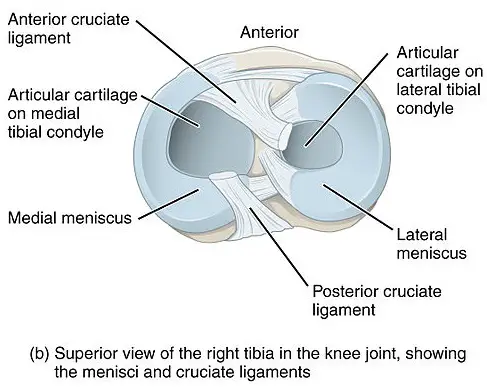

Inside the knee, there are small, tough discs called menisci that help cushion and stabilize the joint. These discs differ in size and how they are attached. The muscles, ligaments, and soft tissues surrounding the knee also play a major role in keeping it stable. Some act like tight ropes (ligaments) that allow a small degree of movement when the knee moves.

(Image: BruceBlaus)

Posterior knee nerves

Nerves in the back of the knee can influence posterior knee pain:

- Tibial nerve: innervates ankles and toe muscles

- Common fibular nerve (peroneal nerve): innervates extensor muscles of the ankle and toes

- Sural nerve: innervates the posterior aspect of the lower leg and lateral foot

These nerves stem from the sciatic nerve, a major contributor to sciatica. A layer of popliteal fascia covers these nerves, which separates it from the medial cutaneous sural nerve and the small saphenous vein.

Along with inflammation, infection, and central sensitization, damage to these nerves may also contribute to posterior knee pain.

Causes and symptoms of pain behind the knee

Causes of posterior knee pain come in a garden variety, similar to other types of knee pain and shoulder pain. Sometimes a combination of these factors can cause pain.

Osteoarthritis and Baker’s cysts

Osteoarthritis can cause posterior knee pain in a few ways.

- The breakdown of cartilage in the knee joint leads to inflammation, which can cause fluid buildup and swelling that drains towards the back of the knee, resulting in a Baker’s cyst— sometimes called a popliteal cyst or bursa.

- Excess fluid production in the knee joint due to osteoarthritis can accumulate in a bursa between the gastrocnemius and semimembranosus muscles. This bursa is located in the medial part of the popliteal fossa, causing it to enlarge into a Baker’s cyst.

- Calcification or injury to the popliteus muscle and tendon at the back of the knee could occur with osteoarthritis. This may also contribute to Baker’s cyst formation in some cases.

The cyst may rupture if there is a fast accumulation of fluid in it, and the fluid may leak out into surrounding tissue, causing further inflammation. Symptoms may be a sensation of “water running down the calf” and swelling and sharp pain in the calf muscles.

Keep in mind that while knee osteoarthritis can increase the risk of getting knee pain, a 2018 systematic review of 63 studies found that some people with osteoarthritis have no pain. Researchers pooled data from nearly 5,400 knees among more than 4,700 adults, they found that about 4% to 14% of the patients who were less than 40 years old showed signs of osteoarthritis. Among those who are 40 and higher, about 19% to 43% are asymptomatic.

Hamstring strain

A hamstring strain is the tearing or overstretching of one or more of the hamstring muscles. It often occurs at the long head of the biceps femoris during the end phase of the leg swing when you sprint.

Research finds that hamstring strains are more common toward the hip rather than toward the knee. However, the pain may radiate down or may be felt at the back of the knee.

Interestingly, tears or other types of injuries do not necessarily cause pain or dysfunction. In a 2016 study of 506 hamstrings from 253 patients with no hamstring or knee pain, 15% of them had a partial tear on both hamstrings and 2% had complete tears on both sides. These tears seem to be more common among older adults than younger adults.

PCL tear

The posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) is one of the four ligaments that attach the femur to the tibia and assist in knee movement. It connects the tibia at the space between the medial and lateral condyles and the lateral of the medial condyle of the femur.

It’s the largest and strongest knee ligament, which makes it less prone to tearing and straining. Still, it can still tear, and isolated PCL tear is much less common than other ligament tears, with a prevalence of 2 cases per 100,000 people in the U.S., according to the Mayo Clinic study.

However, the researchers wrote that pain from PCL tears are seldom isolated causes. Risk factors that increase the likelihood of getting a tear include knee arthritis and the need for a knee arthroplasty.

Meniscus tear

Research finds that meniscus tears are often asymptomatic and do not affect normal knee function much. According to a 2014 review, four studies on the prevalence of meniscus tears show that “healthy knees and osteoarthritic knees with a meniscal tear are not more painful than those without a tear.”

A 2020 study on 230 sedentary adults in the U.K. found that nearly all the subjects had at least one knee “abnormality,” where about 30% of them had a meniscus tear. Thus, it’s unlikely that meniscus tears would be a major cause in the pain behind the knee, but clinicians should not completely rule out this option.

(Image: BruceBlaus)

Calf strain

A calf strain is a muscle tear in the gastrocnemius muscle that often occurs when the knee is fully extended and the foot is dorsiflexed during strenuous activities. It’s more common to get a strain in the medial side of the calf muscle than the lateral.

In a 2017 systematic review of 10 studies of more than 5,300 athletes in various sports (e.g. basketball, rugby, soccer), increasing age and previous calf injury are the highest predictors of whether someone would get a calf strain or not.

Deep vein thrombosis

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is a blood clot that forms in the veins deep in the posterior thigh or the lower leg. Risk factors include:

- trauma to the vein

- high venous pressure

- reduced blood flow

- increased blood viscosity

About 1 out of 1,000 adults in the U.S. have this condition, and there’s a 5.5% chance that death can happen within a month of diagnosis of DVT, according to a 2017 retrospective study.

If DVT occurs in the leg, symptoms may include:

- Pain behind the knee

- Swelling of the tissues near the blood clot

- Reddish and warm skin

- Tenderness to touch

Do exercises help with pain behind the knee?

Exercise can alleviate posterior knee pain by strengthening the surrounding muscles and joint while building self-confidence and self-efficacy.

A team of researchers from the University of São Paulo identified three primary phases of exercise treatment:

- Phase 1: restore normal neuromuscular control and prevent the formation of tissue fibrosis. These exercises would consist of low-intensity, strengthening exercises when the hamstrings and the knee joint are isolated.

- Phase 2: Exercises intensity is increased and focuses on eccentric strength, which is the lengthening of muscles under tension. Current evidence shows some effectiveness of eccentric strength training for both healthy people and recovering patients.

- Phase 3: Higher intensity eccentric strength exercises with plyometrics and sports specific drills should be the primary focus.

Also, research found benefits to exercise for knee pain in general. A 2015 Cochrane Review found that osteoarthritic knee pain was “significantly reduced” when compared with other types of non-exercise intervention among 44 randomized controlled trials. Thirteen trials found that general exercise improved the quality of life among those who exercised compared to those who did not exercise. However, the benefits appeared to be short-term.

Examples of eccentric strength training would be:

- Nordic hamstring curls

- Hamstring curls, prone or seated

- Quadruped single leg extensions

Does massage help reduce knee pain?

Massage for posterior knee pain is similar to general knee pain, which includes Swedish massage, lymphatic drainage massage, and other forms of light-touch massage may help reduce pain and psychological distress associated with pain.

Slow and gentle pressure should be applied to your tolerance and should not invoke pain or discomfort. If the massage is painful or uncomfortable, do not hesitate to let your therapist know immediately. If the back of the knee is too sensitive to touch, massage above and below the painful area.

Like with other types of muscle and joint pain, massage therapy can reduce pain by several mechanisms:

- Descending modulation: the process by which the brain influences nociceptive signals in the spinal cord, either amplifying or dampening them, thereby regulating the pain experience.

- C-tactile activation: Special touch receptors called C-tactile (CT) afferents in the skin, which respond to slow, gentle touches, creating a pleasant feeling. These receptors send signals to the insular cortex in the brain, contributing to positive emotional experiences and self-awareness.

Massage therapists should coordinate with your physical therapist and/or other health provider to understand any specific precautions or areas of focus for your recovery.

Further reading

How Central Sensitization Affects Chronic Pain

How Massage Can Help Treat Chronic Pain

What Is Pain and Why Do We Feel It?

A native of San Diego for nearly 40 years, Nick Ng is an editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine, an online publication for manual therapists and the public who want to explore the science behind touch, pain, and exercise, and how to apply that in their hands-on practice or daily lives.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a B.A. in Graphic Communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014.

When he is not writing or reading, you would likely find him weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, or exploring new areas to walk and eat around Southern California.