Iliotibial band syndrome (IT band) is a painful condition that most often affects runners, especially those who run long distances, other athletes whose sports involve a lot of running or legwork, such as skiers, cyclists, and soccer players, or those who are new to exercise.

Symptoms can manifest as hip pain, knee pain, or a combination of both.

But anyone may suffer from it. I’m not an athlete, but my left IT band and thigh are tender to the touch. Since I can reach that area myself, I frequently massage it. After warming the tissue with a lighter massage, I put as much pressure as I can using the heel of my hand or my knuckles.

I cannot say self-massage helps much, but I feel better to think I am doing something to help it. During the COVID-19 pandemic, I’ve been doing self-massage since early March of 2020, breaking a habit of three decades of getting frequent massages.

The frequency of IT band syndrome is inexact, depending on which study you’re reading. A 2012 systematic review estimated the incidence to be between 5 to 14 percent. In reality, those numbers are based on the number of people who actually sought treatment or agreed to participate in a research project. Therefore, the actual numbers may be higher.

During my own 20-plus years as a massage therapist (currently on hiatus due to COVID-19), I worked with many runners who had symptoms, most of whom had not sought any diagnosis or treatment at all, and kept running in spite of it. Maybe it was their dislike of going to the doctor, their stubbornness, or the old “no pain, no gain” attitude at play.

So is massage good for IT band syndrome? Well, let’s take a look at what science says.

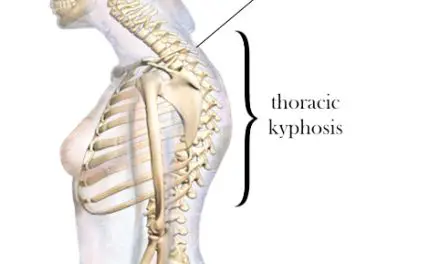

Anatomy of the IT band

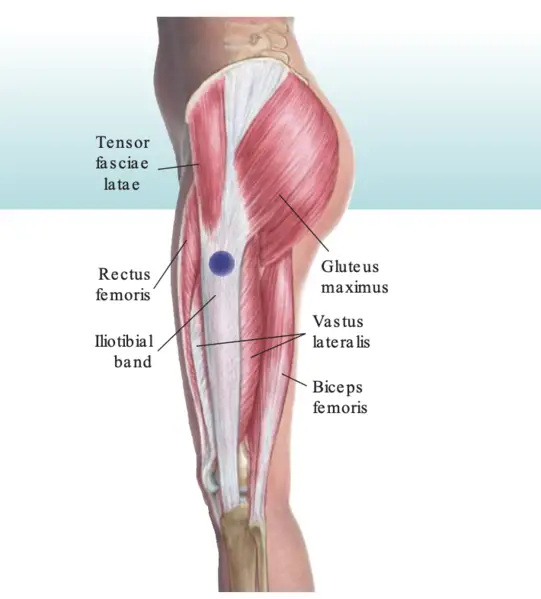

The iliotibial band is somewhat of an enigma. Researchers disagree on the exact anatomy of the IT band and the exact etiology of symptoms associated with IT band syndrome. Basically, it’s a strong, thick fibrous band of the fascia lata of the lateral thigh, beginning at the iliac crest, crossing over the knee, and extending to just below the knee on the outer side of the anterior tibia.

Image: Powellle https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lateral_Trochanter_IT_band_CS.png

Where the tendon passes the knee (lateral femoral condyle), there’s a bursa, a small, fluid-filled sac between the bone and the tendon, which cushions the parts and serves to reduce friction caused by movement.

This tendon moves over a bony process, or bump, at the outer knee as it passes in front and behind it. While many animals share anatomical features similar to those of humans, the function of the IT band is unique to humans. Innervation to the tensor fascia lata (TFL) arises from the superior gluteal nerve.

The IT band stabilizes the knee, both in extension and partial flexion, and is used constantly during walking and running. When you lean forward with the knee slightly flexed, the IT band is the main support of the knee against gravity.

The TFL attaches to the anterior edge of the IT band and part of the gluteus maximus attaches to the posterior edge. Together, they tense and control this deep fascia.

IT band syndrome symptoms

IT band friction syndrome, as it was called when first identified in 1975 by James W. Renee, was described as “a painful disabling condition lateral to the knee.” Renee, a Lieutenant Commander in the U.S. Naval Reserve Medical Corps, observed this phenomenon in soldiers who were undergoing rigorous physical training daily. There was no trauma or injury to the knee itself.

Renee noted that the symptoms of pain and limping were most evident after running for two miles or more or hiking ten miles or more. It’s also likely that the recruits were doing at least some of these activities while carrying heavy packs and equipment.

Renee noted that walking became painful, and in his words, running became “nearly impossible.” He also said that the symptoms generally lasted from two to five days and occurred in intervals ranging from three months to five years.

The main symptom is pain on the lateral knee, but IT band pain may occur anywhere along the band from the hip to the knee, including pain on the back of the knee. Inflammation and swelling may be present.

Pain intensity may be related to the position of the knee at any given time. Sufferers have frequently reported that the pain was worse when their feet were striking the ground and that full extension of the affected leg provided some relief.

The onset of IT band syndrome is not a “sudden” pain, such as spraining an ankle. Instead, it’s more evident at the end of a run, when running uphill, or even climbing stairs.

Although Renee named the condition with the word “friction” included, there’s conflicting evidence that friction has anything to do with it. In fact, there’s conflicting evidence on almost everything to do with the IT band, including its anatomy, causes, and treatments.

Paul Ingraham, a science writer and former registered massage therapist in British Columbia, said that IT syndrome is surprisingly “neglected by science” and “remains mostly unexplained.”

While several myths about it persist—like the idea that it is a “friction” syndrome, which the evidence clearly points away from—Ingraham later backed up on that when newer research was published.

For example, a 2006 study by Fairclough et al. challenged Renee’s theory of friction and the anatomy of the iliotibial band. The newer theory was that IT band overuse injuries may be more likely to be associated with fat compression beneath the iliotibial tract rather than with repetitive friction as the knee flexes and extends.

The researchers based their findings on 15 cadaver studies, plus magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) on six asymptomatic volunteers, and two athletes with acute cases of IT band syndrome. The study concludes that the perception of movement of the IT band across the epicondyle is an illusion.

In 2013, a study by Jelsing et al, in Ingraham’s words, “debunked his debunkery.” Jelsing utilized sonographic evaluation and concluded that the IT band does in fact move anteroposterior relative to the lateral femoral epicondyle during knee flexion-extension and relative to the femur during the functional changes of knee motion.

IT band syndrome causes

The condition is common enough among runners that it’s often referred to as “runner’s knee”—not to be confused with the other “runner’s knee,” patellofemoral pain syndrome, which causes pain on the anterior knee, not the lateral knee associated with IT band syndrome.

Studies of IT band syndrome causes often have small samples, and its data seems to have been influenced by gender, height, and weight of the participants. One conclusion was that being female may be more predisposed to develop the condition.

As mentioned earlier, there’s disagreement among researchers on the exact causes of IT band syndrome, and it’s generally viewed as an overuse injury. This is based on conflicting evidence found in data collections using runners as subjects.

For example, it’s not clear whether hip abductor weakness is a factor. The 2012 systematic review analysis showed that the movement and forces of the hip, knee, ankle, and foot appear to be considerably different in runners diagnosed with IT band syndrome to those without it.

Some researchers suspected that inflammation of the bursa sac is involved, but it’s unclear whether that is causative or multifactorial. However, according to Fairclough’s study that disputed friction being the cause, bursa is rarely present but may be mistaken for the lateral recess of the knee.

While IT band syndrome is not indicative of trauma of the knee itself, there are times when an underlying pathology in the knee, including arthritis or a previous injury, could cause exacerbation of the symptoms.

People may not think of running as a particularly dangerous sport—certainly not as dangerous as downhill skiing or running Pamplona Bull Run—but a literature review concluded that the risk of incurring a running-related injury ranges from 24 to 85 percent.

That’s a big range and there could be many factors at play, such as what type of surface you are running on, whether you are wearing good running shoes, and even the weather.

A 2013 literature review identifies risk factors for IT band syndrome: pre-existing tightness of the IT band, high weekly mileage, time spent running or walking on a track, interval training, and muscular weakness of knee extensors, flexors, and hip abductors.

Overuse, in this paradigm, is synonymous with a repetitive motion injury: you do something enough times, and it puts strain on an area. Running, skiing, rowing, cycling, and even walking all involve repetitive motions.

The harder you push yourself, and the more frequently you do so without adequate recovery time in between, the more likely an overuse injury becomes.

Iliotibial band stretches: does it work?

Some clinicians may recommend stretching the IT band, but it’s almost impossible to stretch. It’s thick, fibrous, and tough, and it would take superhuman strength to make a tiny change in its structure. As mentioned earlier, the IT band is unique to humans, but you can get some idea of how tough it is by examining the fascia on a piece of meat, such as a whole tenderloin.

When “peeling” a tenderloin to prepare it for cooking, you insert a sharp butcher knife at one end of the silver-looking fascia and slide the knife directly under it down the length of the meat, and it will “peel” right off. Put one end in each hand and try to stretch it.

Good luck with that! It’s the same with your IT band, and it’s as tough as that fascia. However, that hasn’t stopped many doctors, physical therapists, and personal trainers from recommending stretching for it.

There are no stretches or exercises that specifically isolate the IT band. Most lower body strength exercises, such as squats and lunges, integrate the IT band with the other hip and leg muscles. Exercise could have an analgesic effect on IT band syndrome.

Foam rolling has become a popular treatment for enhancing athletic performance and for accelerating post-exercise recovery.

Basically, the athlete uses their own body weight to apply pressure to the soft tissues via the foam roller. The rolling motion stretches the soft tissue and creates friction between the tissue and the foam roller.

A meta-analysis of 21 studies on athletes using foam rollers (14 studies looked at pre-event use; seven looked at post-event use) concluded that effects on athletic performance and recovery are probably minor, and that it’s probably more valuable as a warm-up method than a recovery tool.

We should remember that people who are in pain, athletes or not, are looking for something to help them feel better. Since foam rollers are cheap and easy to use with minimal instructions, some sufferers may find them helpful.

Is massage good for IT band syndrome?

Unless a client is an athlete who happens to be savvy about injuries, or one who has actually been to a doctor for a diagnosis, they may not know what’s going on. All they know is they are in pain. What can massage therapy do for IT band syndrome?

First, there’s no cookie-cutter massage routine for IT band syndrome (nor hopefully, a cookie cutter routine for any issue). Each client or patient is unique, and although the pain from this syndrome may be located in the same place on many people, the response to it depends on the individual.

Some people have a high pain tolerance, some are stoic or stubborn about pain, and people with a low pain tolerance may seem more debilitated by it.

Regardless of massage modality, warm the area and do not work beyond the client’s comfort level. Some therapists think they need to go to the bone, regardless of the problem or how tender the client is, and that is not being client-centered in any way. The idea that light work is not as effective as using a heavy hand is false and outdated.

That’s not a directive not to use deep tissue massage, but a reminder to honor the client’s comfort level. When you hurt a client, especially one who’s already in pain, they tend to tense up even more. The same goes for doing joint mobilizations and stretches, both active stretching and passive stretching. Don’t go beyond the client’s pain tolerance.

Some physical therapists recommend foam rollers, and those are not out of scope for massage therapists. Massage tools that mimic the action of the human hand as within scope.

Some therapists may use a vibrating tool, like a massage gun, with the intention of “loosening up” the IT band and thighs. If you do choose to use something like that, be sure it’s within your scope of practice, which varies according to your jurisdiction and whether or not massage is regulated in your state or country.

Topicals may provide temporary relief. Avoid applying anything that is medicated or using essential oils without checking with the client. They may have allergies or just plain dislike the smell or sensation of something.

A 2013 review compared ten studies that used a variety of treatments used with athletes who were diagnosed with IT band syndrome. This included deep tissue massage with transverse friction that was used in one study.

Overall, the researchers concluded, “from clinical experience, rest is the best treatment for the acute cases. This treatment becomes less useful as it becomes a more chronic condition when bursal and periosteal changes have set in.”

There’s limited evidence to support one specific approach to the treatment of IT band syndrome. However, the evidence currently shows that a combination of rest of about two to six weeks, stretching, pain management, and modification of running habits produces a high return-to-sport rate.

While we would like to think massage therapy is helpful for everything and everybody, that is simply not true. One person may have a great outcome while another calls you the next day to say they have not felt any relief. Do your best work and don’t take it personally.

One thing that’s certain about the IT band and iliotibial band syndrome is that nothing is certain. While there are many studies on knee pain in medical databases, the number of studies on iliotibial band syndrome are relatively small, compared to many other pain problems.

For comparison’s sake, as of September 2020, a search on PubMed for “iliotibial band syndrome” has 332 results, but a search for “rotator cuff tear” has more than 8,800 results, and “ankle sprain” has more than 19,000 results.

The only thing that trumps science is better science, and I hope that more and better research on IT band syndrome will be done.

Feature photo: Body Mechanics Orthopedic Massage

Laura Allen, LMT

Laura Allen is President of Sales & Marketing of CryoDerm. A graduate of Shaw University and The Whole You School of Massage Therapy, Allen has been a licensed massage therapist since 1999 and an Approved Provider of Continuing Education under the NCBTMB since 2000. She has taught classes all over the U.S., Canada, and Europe.

She is the author of The Educated Heart, Cultural Crossroads of Healthcare and Healing, and numerous other books. Allen resides in North Carolina with her husband, James Clayton, and their two rescue dogs.