An LCL injury refers to a tear or sprain to the lateral collateral ligament, which is on the outer side of the knee. The ligament connects the femur to the fibula and works with the medial collateral ligament (MCL) to limit side-to-side motion of the knee and brace it against unusual movement. They keep the knee in a rigid position while standing, and assist the joint when the leg is in motion.

In a study of 6.6 million U.S. emergency room visits for knee injuries from 1999 to 2008, about 42% were diagnosed as ligament injuries, mainly from young to middle-age patients who participated in sports and other physical activities.

Massage therapy for an LCL injury

Massage therapy may alleviate some symptoms of an LCL injury, but that depends on the injury grade.

The grades of a lateral collateral ligament (LCL) tear are classified into three levels of severity:

- Grade 1 (Mild): A minor tear where the LCL is overstretched but not significantly damaged. Symptoms include mild tenderness and swelling with little to no instability in the knee.

- Grade 2 (Moderate): A partial tear of the LCL, resulting in more significant pain, swelling, and bruising. The knee may feel somewhat unstable, and there’s usually a noticeable reduction in range of motion and strength.

- Grade 3 (Severe): A complete tear of the LCL, leading to severe pain, swelling, and bruising. The knee is often unstable, and there’s a substantial loss of function and mobility. This grade often requires surgical intervention for full recovery.

These classifications apply to all ligaments in the body, including the MCL, ACL, and PCL.

Massage is not recommended for early onset of an LCL injury since it may increase swelling, inflammation, and pain. While there’s no established research to guide and inform therapists and patients how long you should wait, the best approach is to consult with your physician and physical therapist when you may get a massage.

Given the nature of ligament injuries and knee pain, massage therapists could work around the injured area, such as the quadriceps, hamstrings, and calves to alleviate stiffness and decrease pain. Gentle massage techniques should be used, such as Swedish massage and lymphatic drainage massage. A bolster or pillow underneath the knee can help alleviate some tension.

Massage therapists should collect a health history and perform a thorough intake. A visual gait assessment will allow them to observe if you are limping and bearing more weight on the uninjured leg.

They should also find out if you have seen your doctor for a diagnosis, and if you had one, you should tell them what the treatments were.

If you haven’t had a diagnosis, no massage therapist should make one. However, there are orthopedic assessments that are within a massage therapist’s scope of practice, that may indicate you need a referral to a physician.

Another word about orthopedic assessment: While the term orthopedic massage gets bandied about in massage therapy, there is not strictly one technique that is described as orthopedic massage. The orthopedic part is the assessment.

Massage therapists may integrate any massage techniques with the intention of helping restore restricted movement and treating pain. However, be wary of therapists and sports medicine physicians who subscribe to the theory that you should perform cross-fiber friction “to break up scar tissue/adhesions.” Massage should be done lightly on any recent injury—and if you had a recent surgery, massage shouldn’t be done at all without your doctor’s permission.

Keep in mind that massage is not going to repair a torn ligament. It may help the pain, but that depends on the technique and the pressure applied, which should never be beyond your pain tolerance.

Diagnosis

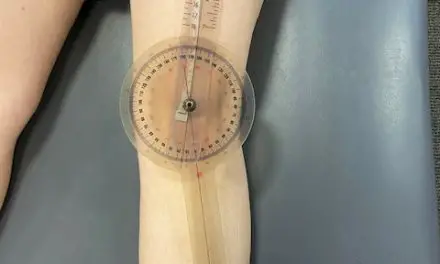

After a thorough health history intake and physical examination, your physician or physical therapist may use a varus stress test is used to test the integrity of the structures that prevent lateral stability of the knee.

- You lie on your back on the examination table with the affected knee in full extension.

- The clinician stabilizes your affected leg with slight external rotation with one hand on the lateral malleolus.

- The clinician places their other hand on your inner knee. Then they apply stress laterally on the medial knee.

- The clinician flexes your knee to 30 degrees, applying the same pressure on the lateral knee to isolate the lateral collateral ligament.

A positive sign means there is pain and hypermobility at the outer knee.

Other tests like the external rotation recurvatum test, posterolateral drawer test, and reverse pivot shift test may be used to check for associated posterolateral corner injuries.

LCL anatomy

The LCL stretches from the lateral epicondyle of the femur and attaches to the head of the fibula. It receives blood from the popliteal artery and from branches of the superior and inferior lateral genicular arteries. Nerve innervation is supplied by the branches of the fibular (peroneal) nerve.

Interestingly, the LCL is highly inconsistent in its anatomy, and some researchers suggest a new classification for it altogether. These findings were based on dissection of 111 lower limbs, which found that about 72% of the LCLs originate from the lateral femoral epicondyle and inserts on the lateral surface of the head of the fibula.

Other variations include:

- 12.6% were divided into two branches

- 0.9% were divided into three branches

- Some ligaments were also found with two and three distal bands

One limb had a double LCLs, and another had a fusion of the LCL and the antero-lateral ligament.This seems like a lot of variations in a relatively small study, but variations in anatomy of the knee ligaments are an important consideration when physicians decide how to treat tears.

A study of 23 cadavers found that the femoral insertion of the antero-lateral ligament overlapped the LCL in all dissected knees, and 15 of them also had thin attachments to the lateral meniscus.

Causes

An LCL tear may be caused by:

- Direct force to the side of the knee when the foot is on the ground

- Awkward landings from a jump, such as in basketball or volleyball

- Twisting and pivoting of the knee

- Varus deformity where the legs curve outward

Related: Does a Larger Q-angle Cause Knee Pain?

If you have a previous knee injury, you’re more likely to get a ligament tear. In a longitudinal cohort study of young adults of more than 5,200 people with previous knee injuries and nearly 143,000 people who had not been injured, the researchers found that those with a previous injury are six times more likely to develop osteoarthritis, with highest risks found after injury to the cruciate ligament, meniscus, and intra-articular fracture.

Related: What Is Foot Pronation?

Risk factors

Risk factors of getting an LCL injury include:

Participating in contact sports like football, soccer, and rugby where there is a higher risk of direct blows or impacts to the outside of the knee

- Sports and physical activities that involve sudden twisting, pivoting or rotational movements that can put excessive stress on the LCL

- Being male: studies have found that males have twice the rate of collateral ligament injuries compared to females

- Older age

- Motor vehicle accidents

- Falls to the outside of the knee

- Body mass index (BMI): While some studies found increased BMI to be a risk factor for lower limb injuries, a 2018 study of more than 500 knees did not find a significant association between BMI and LCL injuries.

One study of 51 knees concluded that isolated collateral ligament injuries are rare in adolescent athletes. MCL injuries—25% of which occurred with kneecap dislocation injuries—were four times more prevalent than LCL injuries. Football and soccer players suffer the most Grade 3 collateral ligament injuries, accounting for 20% to 25% of the cases.

A study of NFL players also concluded that isolated complete tears of the LCL are rare, as the majority of injuries are part of broader damage to the posterolateral corner. There’s limited data about the ideal management of isolated LCL injuries, especially among professional athletes.

Related: Jumper’s Knee

A 2017 literature review reveals a high injury rate in alpine ski racing, with knee injuries being the most common and significant—particularly ACL injuries. This often happens during competition when the athletes are fatigued, though most athletes do eventually return to competition.

A case report details a 28-year-old female Olympic alpine skier who, after sustaining a severe knee injury with multiple ligament and meniscus tears, underwent successful knee reconstruction surgery and competed in the 2018 Olympic trials and Winter Olympics within 14 months.

A U.S. Army study from 2013 analyzed soft-tissue knee injuries in active-duty soldiers from 2000–2005, finding that injury risk increased with:

- Years of service and age

- Previous non-soft tissue patella injuries increased the risk of subsequent injuries tenfold

- Deployment raised the risk by 33%-39%

Symptoms of LCL Injury

The symptoms of LCL injury are

- Pain at the sides of your knee. MCL injury results in pain on the inside of the knee; an LCL injury results in pain on the outside of the knee.

- Swelling and bruising over the site of the injury.

- The feeling that the knee is unstable

- A person suffering a traumatic tear of any ligament may hear the “popping” sound at the time of the injury.

Assessment for damage to collateral ligaments can be assessed by having the patient medially and laterally rotate the leg. Pain during medial rotation indicates damage to the medial ligament, pain during lateral rotation indicates damage to the lateral ligament.

LCL Injury Treatments

Treatment depends on severity of the injury, which may be diagnosed by physical examination but is confirmed with MRI and whether the injury is isolated to the LCL or involves multiple ligaments. All grades of an LCL injury can be treated with:

- RICE method (rest, ice, compression, elevation), especially in the acute phase

- Pain medications (NSAIDs)

- Knee bracing

- Physical therapy, includes exercise

To avoid causing cold injury to the common peroneal nerve, ice should be applied to the lateral knee for no longer than 15 minutes at a time.

For Grade I and II injuries, treatment is usually a conservative approach of crutches for one week, followed by three to six weeks of hinged bracing and physical therapy.

For Grade III injuries, reconstructive surgery may be used to reduce pain and restore range of motion. This is normally done by taking a graft from the semitendinosus allograft.

Exercise

Exercise can help restore some knee range of motion and strength. Depending on the grade of the injury and whether surgery is involved, your physical therapist may recommend some of these exercises. Sets, reps, and tempo can vary, depending on your ability to perform and pain tolerance.

Sitting heel slide

- Sit on the floor with your legs extended as much as you can in front of you. The floor should be smooth to allow a carpet tile, cloth, or a similar object that allows you to slide.

- Place a carpet tile, cloth, or a similar object beneath your heel on the same side as the injured leg.

- Bend your injured knee as much as possible. If you feel pain or restriction, stop at that range of motion. Then return back to the starting position.

- Perform 10 sets of 5 reps. At every fifth repetition, keep the knee in the bent position for 30 seconds.

Passive knee extension

- Sit on a chair and prop your leg up with a chair and let gravity gradually straighten the knee.

- Place your hand on top of your knee to assist the extension if needed, if there’s no pain, and if it doesn’t damage the ligament.

Hip bridge with stability ball

- Lie on the floor on your back and put your lower calves and heels on a stability ball.

- Lift your buttocks off the floor as high as you can.

- Hold the position for 1 to 2 seconds, and lower your buttocks to the floor.

Wall squats

- Stand with your back against a wall with your feet about shoulder-width apart and about one foot away from the wall.

- Squat down while sliding your back against the wall as low as you can.

- Stand up when you’ve reached your deepest squat level. Keep your knees and feet forward.

Single-leg deadlift

- Stand on your affected leg.

- Bend forward at your hips and reach toward the ground while keeping your back as straight as you can. Avoid hunching.

- Bend your standing leg slightly if needed and there’s no pain.

- Extend your other leg behind you as you bend forward.

- Return to the starting position and repeat.

- You may use a kettlebell, dumbbell, or a similar object to pick up.

The last two exercises are more advanced than the first two and should be done when later phases of the rehab program.

Further reading

Can a Lateral Meniscus Tear Heal Itself?

How Massage Can Treat Chronic Pain

Massage for Joint Pain: A Biopsychosocial Approach

Laura Allen, LMT

Laura Allen is President of Sales & Marketing of CryoDerm. A graduate of Shaw University and The Whole You School of Massage Therapy, Allen has been a licensed massage therapist since 1999 and an Approved Provider of Continuing Education under the NCBTMB since 2000. She has taught classes all over the U.S., Canada, and Europe.

She is the author of The Educated Heart, Cultural Crossroads of Healthcare and Healing, and numerous other books. Allen resides in North Carolina with her husband, James Clayton, and their two rescue dogs.