Your knee consists of a medial and a lateral menisci, one on the inner side (medial) and one on the outer side (lateral), situated between the respective ends of the femur and the tibia.

A medial meniscus is a C-shaped cartilage that acts as a cushion and provides stability by distributing weight and reducing friction during movement. It helps absorb shock and prevents the bones in the knee from rubbing against each other.

In the developing fetus, the meniscus has a complete blood supply, but by adulthood, that goes down to 10% to 25% for the medial meniscus and 10% to 30% for the lateral meniscus. This is supplied peripherally by the popliteal artery. The meniscus receives nutrients from joint movement and synovial diffusion. The knee is innervated by the sciatic, femoral, and obturator nerves.

Mechanoreceptors, the sensory cells that respond to the sensations of touch, pressure, and stretching of the tissues, are located in the posterior and anterior horns of the medial meniscus.

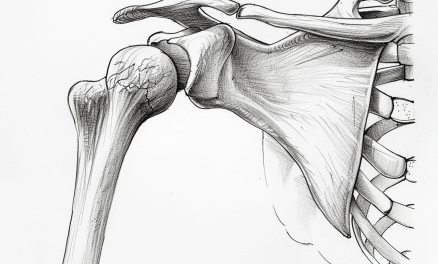

Although people tend to think of the meniscus as being located in the knee, there are also menisci in other parts of the body, such as the wrist, acromioclavicular joint, temporomandibular joint, and sternoclavicular joint. Unlike articular disks, which serve to separate the synovial cavities of the joints, a meniscus only partially divides a joint cavity.

Medial meniscus tear causes

Meniscus tears are classified as traumatic or degenerative based on the configuration of the tear, which also dictates how a physician will treat the tear.

A traumatic tear occurs due to a sudden injury or force on the knee, while a degenerative tear develops gradually over time due to wear and tear on the meniscus as it degenerates. A degenerative tear may lead to horizontal, flap, or complex tear patterns.

Trauma medial meniscus tears can be caused by:

- Sudden twisting

- Cutting and pivoting,

- Tackled or collided with another person or object.

Degenerative meniscal tears can be caused by:

- Arthritis

- Aging

- Repetitive stress

Both types of tears could sometimes be a complex medial meniscus tear, which refers to a tear in the medial meniscus that has multiple patterns or configurations rather than a simple linear tear. Complex tears tend to be larger and more extensive, and involve displacement or fragmentation of the torn meniscal tissue.

Symptoms

Symptoms of a medial meniscus tear can potentially last for a long time and become chronic if left untreated. Symptoms may include:

- Pain, often localized to the inner side of the knee

- Swelling or inflammation around the knee

- Difficulty or pain when bending or straightening the knee

- Clicking, popping, or locking sensations during movement

- Instability or a feeling of the knee giving way

- Limited range of motion in the knee

- Difficulty bearing weight on the affected leg

- Feeling of “giving out” or buckling during activity

Acute symptoms like pain, swelling, and limited range of motion usually develop over two to three days after the initial injury. However, these symptoms may persist for weeks or months without proper treatment.

If the tear is small or stable, the initial symptoms may subside but can recur intermittently with activities that stress the knee joint, leading to a chronic condition.

Larger, more complex medial meniscus tears often cause more severe and persistent symptoms that do not resolve on their own. Pain may come and go over years if left untreated.

Related: Lateral Meniscus Tear: Do You Need Surgery?

Risk factors of getting a medial meniscus tear

Similar to lateral meniscus tears, risk factors to getting a medial meniscus tear include:

- Playing contact and/or pivoting sports, (e.g. soccer, basketball)

- Being male

- Age (over age 60)

- Jobs that involve kneeling, squatting, and stair-climbing of more than 30 flights of stairs

- Waiting longer than 12 months to have surgery to repair a torn anterior cruciate ligament. This does not apply to lateral meniscus tears.

Diagnosis

An MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) is the gold standard to confirm diagnosis of a torn meniscus, but physicians would most likely not order that prior to gathering a health history and doing a physical examination.

There are several assessments that are commonly used for a preliminary diagnosis. However, due to the numerous ways a meniscus can be injured, none of the physical assessments have enough diagnostic specificity to be a viable alternative to MRI; they are basically used to confirm that there is an injury.

McMurray test

The McMurray test is performed with the patient supine and relaxed. While grasping the patient’s heel with one hand and the joint line of the knee with the other hand, the examiner brings the knee to maximum flexion, while performing external tibial rotation to check for a medial meniscus injury and internal tibial rotation to check for lateral meniscus injury. During both assessments the examiner fully extends the knee while maintaining rotation.

A positive McMurray test produces a pop or click and pain during range of motion assessment.

Thessaly test

In the Thessaly test, the examiner supports the patient by holding their outstretched hands while the patient stands flat footed on one leg. The patient flexes the knee to 20 degrees and rotates their body three times, medially and laterally.

If the patient experiences medial or lateral joint line discomfort or a sense of locking or catching in the knee, the test is considered positive for a tear.

Apley test

In the Apley test, the patient’s knee is moved into 90 degrees of flexion by the examiner, while simultaneously firmly grasping the patient’s heel. The examiner rotates the leg medially and laterally while applying a downward axial loading force.

A 2015 study found that the McMurray, Thessaly, and Apley tests had a diagnostic accuracy rate of about 53%, 59%, and 54%, respectively. In this study, a primary care clinician and a musculoskeletal clinician examined 292 patients with a knee pathology and 75 patients without any knee issues.

The researchers concluded that the Thessaly test “was no better at diagnosing meniscal tears than other established physical tests. The sensitivity, specificity and diagnostic accuracy of all physical tests was too low to be of routine clinical value as an alternative to MRI.”

Do You Need a Torn Meniscus Surgery?

A meniscectomy is a surgical procedure to partially or completely remove a damaged or torn meniscus from the knee. Surgical repair, rather than replacement, is more likely to be performed on younger patients that have no degenerative disease and a high level of physical activity.

Repairing the meniscus by suturing it back together is also an option. A 2016 study of middle-aged patients with degenerative meniscal injury who were followed for two years after receiving a diagnosis found no significant difference in the outcomes for those who received surgery and those who were treated with supervised exercise (physical therapy) as a treatment.

Another method is debridement, an arthroscopic surgery during which the torn area of the meniscus is basically filed down while leaving the rest intact. It is usually performed for degenerative tears that cannot be repaired.

During a trephination, an alternate method, a circular section is removed, also leaving the rest of the meniscus intact.

In younger athletes, the decision to treat with debridement instead of repairing the meniscus depends on the type and location of the tear, and the patient’s willingness to cooperate with postoperative restrictions.

The transplantation of a meniscus harvested from a cadaver (referred to as an allograft) is a surgical option for patients who are young and active.

The effectiveness of meniscectomy is widely disputed. One study comparing patients who had surgery for a degenerative medial meniscus tear to patients having sham surgery concluded that there was insignificant difference in outcomes, while pointing out that it is one of the most frequently used procedures in spite of the lack of evidence of its efficacy.

Science writer Paul Ingraham wrote that the evidence is “overwhelming that meniscectomy just does not do what surgeons have assumed for a long time.”

However, a 2020 study disagrees and concludes that surgery to save the meniscus is always the best available option, including those that might not be successful. The logic is that even if a repair fails, it’s better to have a 25% chance of a failed repair than a 100% meniscectomy.

Be aware that all surgeries carry some risks and side effects. A 2018 review of 700,000 arthroscopic medial meniscus surgeries from England’s Hospital Episode Statistics database reviewed surgeries performed between April 1997 through March 2017. Within 90 days of surgery, there were 546 incidents of pulmonary embolism, and 944 patients who developed infections that were serious enough to require further surgery. Although the risk is statistically low, the researchers found that the risk had not decreased over time.

A meniscectomy may also increase the likelihood of developing knee osteoarthritis of the knee in many cases. Patients who develop painful catching or locking in the knee may need meniscal repair, which can relieve pain associated with a torn meniscus. Thus, be mindful of the risks vs. benefits when you see your physician.

Medial meniscus tear exercises

Start with low-impact exercises to strengthen muscles and the knee without stressing it. As healing progresses, add strengthening and stretching exercises within a comfortable range of motion. Avoid high-impact, twisting exercises early on.

Researchers from the University of Denmark proposed some of the following exercises for young adults with meniscus tears in a 2018 study These exercises are part of a rehab program.

Sitting heel slide

- Sit on the floor with your legs extended as much as you can in front of you. The floor should be smooth to allow a carpet tile, cloth, or a similar object that allows you to slide.

- Place a carpet tile, cloth, or a similar object beneath your heel of the same side as the injured leg.

- Bend your injured knee as much as possible. If you feel pain or restriction, stop at that range of motion. Then return back to the starting position.

- Perform 10 sets of 5 reps. At every fifth repetition, keep the knee in the bent position for 30 seconds.

Sitting knee extension with cushion

- Lie on your back or sit on the floor with your legs extended in front of you. Place a rolled-up towel or a small therapy ball (about grapefruit size) under the knee of your injured side.

- Contract your quadriceps muscle and push the back of your knee downwards to compress the ball, so that the knee is extended and the heel lifts from the floor.

- Relax your leg and repeat for 2–3 sets of 10 reps.

Sideway slides

- Stand with one foot on a carpet tile or cloth that can slide on the floor.

- Move the foot to the side in a sliding movement while bending and stretching in the opposite knee.

- Repeat with the other leg for 2–3 sets of 8 to 10 reps.

Side lunges

- Stand with your feet about a little wider than your shoulder width.

- Lunge toward your affected leg as low as you can without pain. Your opposite leg should be extended with both feet flat on the floor.

- Return to the starting position. Repeat for 2–3 sets of 10 reps.

Standing Inner thigh adduction

- Tie an elastic band to the ankle of your affected leg. Make sure the band is secured so it doesn’t snap when you stretch it.

- Stand with your feet about shoulder-width apart and with your side to the band’s anchor point. Hold it for support if needed.

- Move the leg toward the center of your body as much as you can or until it crosses your body’s midline slightly.

- Return to the starting position and repeat for 2–3 reps for 10 reps. Repeat with the other leg.

Each exercise can be progressed as you recover and improve your strength, balance, and performance. Your physical therapist or similar rehab specialist would determine the number of sets and reps and what other exercises you can progress to.

Related: What Does a PCL Tear Feel Like?

Can a medial meniscus tear heal without surgery?

It’s possible that a meniscus tear can heal by itself without surgery, but that depends on the degree and the type of tear. It would be up to you and your healthcare provider to decide the best course of action since there’s no cookie-cutter approach to this.

So far, research has shown that some meniscus tears can heal on their own with conservative treatments.

- One study with 32 patients with an ACL tear and torn meniscus were treated with bracing. In three months, 58% of the medial menisci healed completely and none healed partially. Of the 25 people with ACL injuries, 20 of them were healed satisfactorily, and 3 out of 7 people with PCL injuries also healed well. This study indicated that acute tears of the meniscus, even when they occur with a ligament injury, can heal with nonsurgical treatments.

- A study of degenerative meniscus tears concluded that patients treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) and physical therapy compared to patients who were treated with partial meniscectomy resulted in similar long-term results.

- Self-renewing stem cells and platelet-rich plasma (known as orthobiologics) have shown promise in assisting surgical repairs and as stand-alone treatments for torn meniscus, but there has been limited research performed on humans in this area (A search on PubMed reveals numerous such studies on animals). Limited research has not kept orthopedic doctors from jumping on the stem cell bandwagon since there are numerous clinics advertising it as an available therapy.

- Gel injections containing hyaluronic acid (also called hyaluronan), a substance that naturally occurs in joints, fascia, and skin, is being used to treat knee osteoarthritis. A 2019 study showed that a single intra-articular injection of Gel-200 was more effective than placebo (phosphate buffered saline) in improving symptoms like pain, stiffness, and physical function over 26 weeks.

Should you get a massage?

Massage therapy may help alleviate pain and some swelling of the knee that often comes with a meniscus tear. The therapist should avoid touching the injection site if one was made in the past several days.

In your initial session with a massage therapist, you should receive a comprehensive health intake interview to cover pertinent information about your current condition, including specifics about the torn meniscus and any recent or scheduled surgeries or other interventions that your physician is recommending, such as icing, bracing, exercise, and injections.

Massage therapists should always be mindful of the client’s comfort level and pain tolerance. If the client has had recent surgery to repair, remove, or graft that has not yet healed, avoid the area altogether until it has healed. Although the surgery is usually arthroscopic and performed on a relatively small area, you should treat it like any other surgery and avoid massaging directly on the surgical site(s) until the client gets permission from their physician.

If the knee is still inflamed or swollen from the injury, don’t aggravate that problem with aggressive techniques. Swedish massage, light skin stroking, and lymphatic drainage massage should be used instead.

If the client is being treated without surgery, gentle passive movements directed to the quads and hamstrings can be beneficial, while deep tissue massage should be okay above and below the surgical sites, as the client desires.

Some clients may feel better side-lying with the injured knee on top and a pillow between the legs. A bolster or a pillow can be placed under the knees when the client is in a supine position, and under the ankles when prone. In a chair massage, the client may not want to rest their knee on the knee pad if the injury is very recent or painful.

Further reading

Massage for Joint Pain: a Biopsychosocial Approach

Pain Behind the Knee: Causes, Treatments, and Massage

Laura Allen, LMT

Laura Allen is President of Sales & Marketing of CryoDerm. A graduate of Shaw University and The Whole You School of Massage Therapy, Allen has been a licensed massage therapist since 1999 and an Approved Provider of Continuing Education under the NCBTMB since 2000. She has taught classes all over the U.S., Canada, and Europe.

She is the author of The Educated Heart, Cultural Crossroads of Healthcare and Healing, and numerous other books. Allen resides in North Carolina with her husband, James Clayton, and their two rescue dogs.