Passive stretching is a type of stretching where you apply external force onto a muscle that you want to stretch. This can be done either with you holding a stretch with your hands or have another person provide the external force to help you stretch a little further. This allows you to relax into your stretch.

Passive stretching exercises

Although the evidence indicates that static stretching, which includes passive stretching, has little benefits to athletic performance, you can still do it after you workout as a way to relax.

Here are seven passive stretches that you can do to target the major muscle groups, and these are by no means the only stretches available. You may also repeat the stretches one to two times if you feel like doing so.

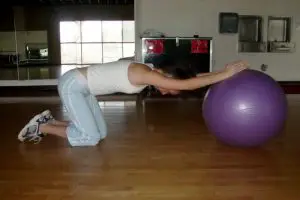

Back stretch with stability ball

Photo: Nick Ng

Kneel on the floor with a stability ball in front of you. Place your hands on top of the ball like you are doing a karate chop. Push the ball forward slowly and lean your body toward the floor until your torso is about parallel to the floor. Shift your weight toward your hips slightly to increase the stretch if you want. Hold this position for about 20 to 30 seconds.

Chest stretch on stability ball

Lie on top of a stability with your feet flat on the floor and your legs bent. Rest your head on the ball and spread your arms to your sides. Let your arms hang and relax as you stretch your chest. Hold this position for about 20 to 30 seconds.

Doorway chest stretch

Stand at a doorway in a split stance position with one foot forward and the other back away from the center of your body. Place your forearms against the door jamb with your elbows bent about 90 degrees. Lean your body forward slightly as you shift your weight toward your front foot until you feel a stretch at your chest. Hold this position for 20 to 30 seconds. You may also do this with feet together or slightly apart—whichever you are comfortable.

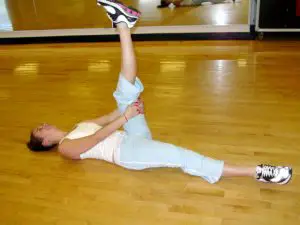

Supine hamstrings stretch

Photo: Nick Ng

Lie on the floor on your back and bend one of your knees toward your face. Hold the back of your hamstrings and extend your leg as much as you can until you feel a stretch. Flex your foot toward your face to get an extra stretch in your calves. Hold this position for 20 to 30 seconds.

Standing quadriceps stretch

Photo: Nick Ng

Stand and bend one of your legs behind you as you grab your ankle or the top of the foot. With the opposite hand, hold onto a sturdy support (e.g. wall, chair, desk) for balance if needed. Hold this position for 20 to 30 seconds.

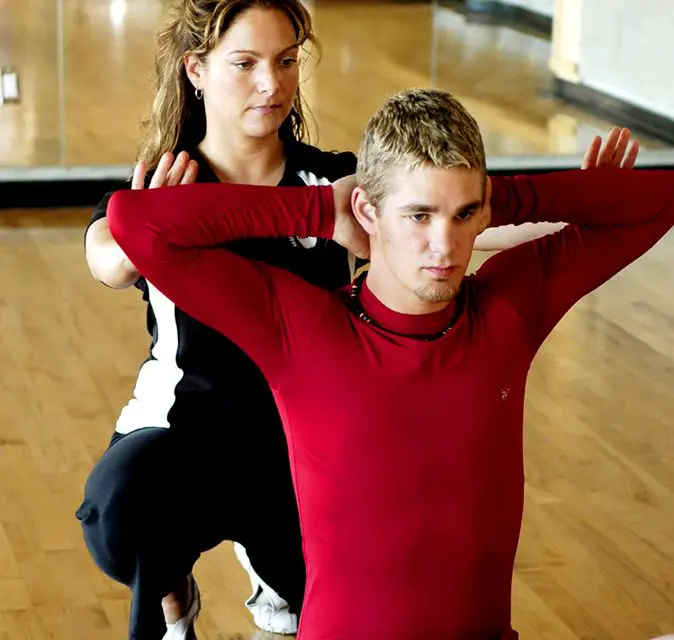

Arm extensor stretch

Standing calf stretch (heel drop)

Stand with your feet slightly apart on the edge of a step or sturdy platform (e.g. aerobic steps). Use a wall or a sturdy object like a chair for balance. Lower your heels toward the floor until you feel a stretch in your calves. Hold this position for 20 to 30 seconds.

Although many people stretch as part of their routine before and after a workout, what does scientific evidence actually say about it?

What distinguishes static from passive stretching?

Passive stretching and static stretching may sound alike at first, but passive stretching is just a type of static stretching, with the other type being active stretching.

Passive stretching, as the name implies, is where you stretch a muscle group by holding the stretch with another body part.

For example, you can stretch your chest by placing your forearms against a doorway while standing and lean your body forward to stretch. Or you can stretch your chest by laying your back on a stability and lay your arms to your sides, allowing gravity to assist the stretch.

Another way to do passive stretching is if you have a workout partner who knows how to safely provide a stretch for you for about 20 to 30 seconds. This is also known as PNF stretching.

Unlike active stretching where you contract the muscle group that is opposite to the muscles you are stretching, the key to passive stretching is to have your body relaxed while you stretch.

Passive stretching vs. dynamic stretching

While passive stretching is like being a statue, dynamic stretching is moving a group of muscles and joints within your full range of motion repetitively, like an animated GIF.

For example, you can passively stretch your hamstrings by lying on the floor and holding the back of your knee or hamstring as you extend your knee to hold the stretch. In dynamic stretching, you could do a sagittal plane leg swing, where you stand and swing your leg forward like you are kicking, and then swing your leg back and bend your knee with a slight hip extension.

If you are more athletic, ballistic stretching might be another option where you perform bursts of repetitive movement—like bouncing—while using momentum to increase your flexibility. While ballistic stretching may increase your risk of injury, it may help you mentally and physically prepared for your upcoming training.

Passive stretching and athletic performance

The scientific literature has mixed suggestions about whether static stretching (passive or active) is beneficial or not to athletic performance. While some studies among athletes suggest little to no benefits of static stretching to performance nor does static stretching reduce the risk of injuries, a 2015 systematic review found that static stretching of various lower-body muscles for 60 seconds or longer—regardless of whether it is passive or active—lowers performance, such as speed and power development in sprinting.

The researchers, led by Dr. David G. Behm of Memorial University in St. John, Newfoundland, reviewed a few hundred studies that examined the acute effects of various types of stretching on physical performance, range of motion, and number of injuries.

Out of these studies, 52 of them examined how static stretching affects speed and power in jumping, sprinting, and throwing, and 76 studies examined how it affects strength (e.g. one-rep max, maximal voluntary contraction). Overall, there was a 1.3% reduction in power and speed and a 4.8% reduction in strength.

However, static stretches that last 60 seconds hardly affects performance (about a 1.1% decrease). The authors concluded that static stretching had “no overall effect on all-cause injury or overuse injuries, but there may be a benefit in reducing acute muscle injuries with running, sprinting, or other repetitive contractions.”

A 2019 review published in Frontiers in Physiology also found similar conclusions. It focused mostly on studies that examined the effects of static stretching on power and strength.

The authors suggested that static stretching could be done before certain strength and power activities as long as the stretching duration of each exercise is less than 60 seconds, and it is incorporated with other types of warm-ups, such as dynamic stretching. For high-power sports (e.g. powerlifting, rugby), static stretching should be avoided.

“There is strong evidence suggesting that [static stretching] causes only trivial negative effects on subsequent strength and power performances if the accumulated duration per muscle group does not exceed 60 [seconds],” the authors wrote. “We should update previous statements on the harmful effects of [static stretching] on strength and power performances.”

But applying research is not as easy as a do-it-yourself manual. Trainers, coaches, and manual therapists would need to evaluate each patient’s or client’s goals and abilities so that they don’t end up doing a one-size-fits-all approach.

“A lot of the research on flexibility aren’t that great,” said Dr. Allan Bacon, who is the co-founder of Maui Athletics in Hawaii. “You would think that this would be something that is extremely easy to study. What I’ve found is that there’s a lot of heterogenity in the results people were getting when they do [stretching].

“I think what we need to think as coaches is how does flexibility aid what the athlete is attempting to do,” Bacon said. “It isn’t a broad thing where everybody stretches all the time and get as flexible as possible or no one stretches at all. [The stretching method] should match whatever sport or athletic ability a person wants to display.”

For example, if you have low flexibility in particular muscle, passive stretching that muscle before training may not be the best option. Bacon suggested that it’s better to do this after workout when the muscles are warmer and looser.

“I think most passive stretching modalities can be used really well in a rehab setting,” he said. “The professional can guide that range of motion. Specifically, when you have issues or an injury, you want to have somebody who have a better understanding of a treatment and be able to control [the stretch].”

For Bacon, he would apply active stretching instead of passive stretching for the majority of his current clients and athletes. Active stretching works within their normal range of motion, and adding extra flexibility to their sport or activity may likely not be beneficial.

Conclusions about passive stretching

Since passive stretching falls under the category of static stretching, you can probably extrapolate some of the information in the research to your own workouts.

To maximize your time, perhaps it is better to perform dynamic stretching and body weight warm-ups, like lunges and leg swings, before you lift or run. Save passive stretching after exercise or before bedtime as a way to relax your body and mind.

A native of San Diego for nearly 40 years, Nick Ng is an editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine, an online publication for manual therapists and the public who want to explore the science behind touch, pain, and exercise, and how to apply that in their hands-on practice or daily lives.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a B.A. in Graphic Communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014.

When he is not writing or reading, you would likely find him weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, or exploring new areas to walk and eat around Southern California.