Forward head posture is where your head sticks too far in front of your body and your ears go past your torso’s midline. Also known as “text neck,” this position is common if you were looking at your smartphone, reading a book, or working at a computer.

Common symptoms of forward neck may include:

- tight deep neck and chest muscles

- headaches

- “pins and needles” and/or numbness in your hands and arms

- “weaker” upper and mid back muscles

- rounded shoulders and kyphosis, which are characteristics of upper cross syndrome.

Some evidence suggests that a forward head posture can reduce your lungs’ and breathing muscles’ ability to maximize air intake. When your head sticks forward to its maximum length, movement in the lower abdominal cavity decreases. “The forward head posture causes expansion of the upper thorax and contraction of the lower thorax,” the researchers wrote.

But keep in mind that some of these studies are based on young men, so it may not apply to women, children, and older adults.

Forward head posture may increase the risk of excessive wear-and-tear in the upper cervical spine, as well as headaches, bone spur development, and nerve impingement. However, these evidence are based on individual case studies and cannot be extrapolated to the general population.

While there are ways for you to “fix” your forward head posture, it doesn’t need to be complicated, and you definitely don’t need to be worried or obsessed about it.

Why?

Because much of the scientific research finds a poor link between neck posture and pain.

So take a deep breath and try out some simple exercises before we examine what research says about forward head posture.

How to “fix” forward head posture with exercise

Exercise in general can provide some neck pain relief, even if you just move your head and shoulders. These movements are an attempt to reverse the forward head.

Take deep breaths as you do these exercises and find your own breathing rhythm.

Chin tucks

Stand or sit up straight and look ahead.

Tuck your chin toward your neck. You might feel your neck muscles tighten in the back of your neck.

Hold this position for 2–3 seconds and relax. Let your head move back to its starting position.

Do 10–15 reps or until you feel slightly fatigued in your neck.

Wall angels

Sit or stand with your back against a wall.

With your arms bent at 90 degrees, place them against the wall so that your knuckles and elbows are touching it.

Push your neck and head toward the wall gently.

Slide your hands and arms up above your head as high as you can with little movement in your back. Try to keep your head and spine close to the wall as you move.

Slide your hands and arms down to the starting position. Perform 10–15 reps or until you start to fatigue.

Nod your head

Tilt your head back gradually to look up.

Hold for a second or two, and then look down.

Repeat 4–5 times or as many as you like until you feel a little “looser.”

Look both ways

Turn your head as far as you can to your right.

Turn your head to your left.

Repeat 4–5 times or as many as you like until you feel a little “looser.”

Lateral neck stretch

Tilt your head to your right to bring your right ear toward your right shoulder like you’re looking for a book on a library shelf. Do not shrug your shoulders.

Then tilt your head to the left. Do the same number of reps as in the previous two exercises.

Do these posture exercises as often as you like. These exercises may or may not correct your neck posture, but you’d likely feel less stiff and painful. If you have pain, restricted range of motion, or both while doing these exercises, consult with a qualified medical profession before further attempting to exercise. These are not substitutions to medical advice or care.

Do forward head posture treatments work?

You might find some pain relief from stretching your neck or using a heating pad. Some treatments can be as dramatic as wearing a neck brace or getting regular spine adjustments. So let’s take a look at what research says about them.

Exercise

Exercise may reduce neck pain and improve the neck posture, but only at the angle between your C7 and the middle of your ear, according to a 2018 systematic review of seven studies with 627 subjects.

Some research shows that exercise can improve the craniovertebral angle (CVA), but not so much further up the neck. Source: (Effects of Abdominal Breathing and Thoracic Expansion Exercises on Head Position and Shoulder Posture in Patients with Rotator Cuff Injury)

However, the researcher noted that the study designs and subjects were all different so we can’t make blanket conclusions about exercise would work for everyone.

For example, a 2020 study of a 4-week exercise program to correct forward head among 30 teenagers in India didn’t find much improvement in changing their neck posture. However, those in the exercise group had better movement and function than the control group.

Kinesio Tape

Taping is a popular way to provide short-term pain relief among athletes. One popular tape is Kinesio Tape, which has been shown to provide some pain relief and improve your body awareness (proprioception).

However, most research shows that it’s not any better than exercise in pain reduction or changing your posture.

Chiropractic adjustments

Chiropractic and other manual therapy adjustments are often sought for changing their neck posture and pain relief.

While some research finds pain relief with neck adjustments among those with acute neck pain, there’s not much difference between exercise only and exercise with neck adjustments.

But keep in mind the risks that are associated with neck adjustments, such as stroke and headaches.

Neck brace

While there are no reviews yet about how effective a neck brace is for forward head or chronic neck pain, research for whiplash injuries finds no benefits of a stiff neck brace for neck pain.

However, neck braces that allow some neck movement are more effective in pain reduction and mobility.

Does forward head posture cause neck pain?

Many people blame forward head posture to be the cause of neck pain, but a lot of research finds that there’s not much difference in posture between those who have neck pain and those who don’t.

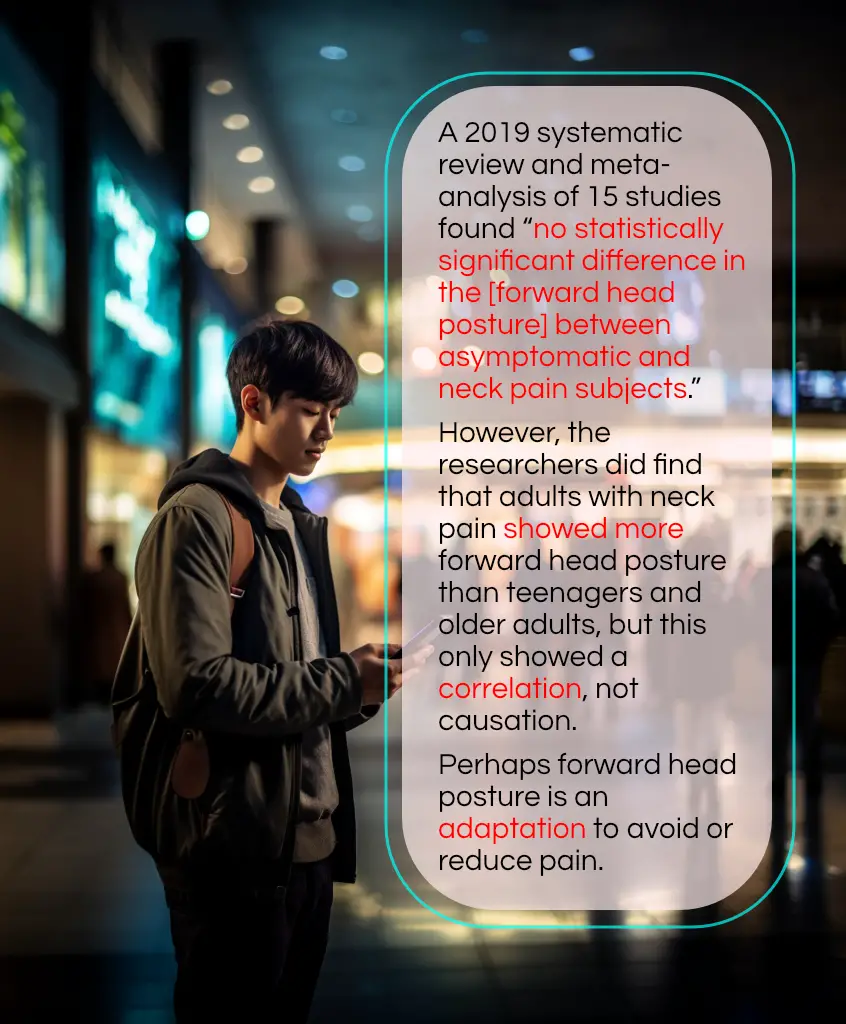

For example, a 2019 systematic review and meta-analysis of 15 studies found “no statistically significant difference in the [forward head posture] between asymptomatic and neck pain subjects.”

However, the researchers did find that adults with neck pain showed more forward head posture than teenagers and older adults, but this only showed a correlation, not causation.

It’s not clear why there’s such a difference, but the authors hypothesized that teenagers tend to have higher muscular endurance in the deep neck flexors than adults. Plus, some adults have adopted the forward head posture far longer than teenagers, which may explain why they’re more likely to have neck pain. But that doesn’t explain why older adults showed similar results as teenagers.

But these ideas do not explain why many teenagers and children suffer from chronic neck pain regardless of what neck curvature they have.

Further research doesn’t support the idea that forward head posture causes neck pain.

- A 2020 Spanish study examined 96 college students from the University of Acalá with 64 students without pain and 32 students with neck pain.

The researchers measured neck flexion, extension, and rotation with students in a sitting position.

They found that those with forward head posture have higher sensitivity and lesser neck range of motion than those with no pain. But they reported that “forward head posture is not associated with the presence of neck pain, headache, or disability.”

Perhaps sticking their head forward is an adaptation to neck pain rather than the posture causing their pain.

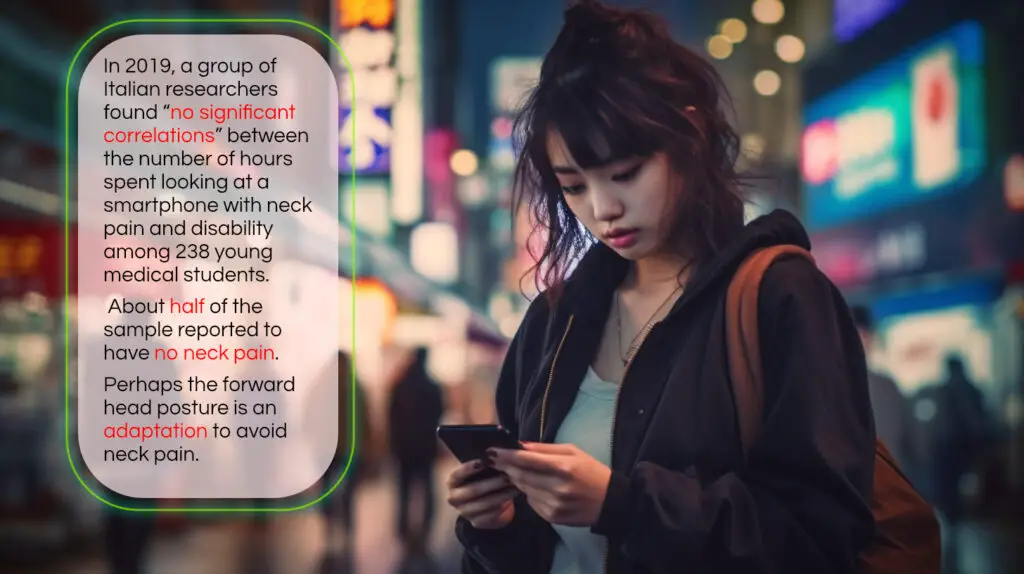

- In 2019, a group of Italian researchers found “no significant correlations” between the number of hours spent looking at a smartphone with neck pain and disability among 238 young medical students. About half of the sample reported to have no neck pain.

They suggested that “young people can continue to use their cell phones as they prefer.”

(Image by Midjourney, illustration by Nick Ng)

- Israeli researchers do not find a significant difference between neck posture and non-specific neck pain among 43 adults. Those with neck pain moved their neck slower and with less range of motion.

- A 2018 meta-analysis from Henan, China, reviewed 21 studies—with a total of more than 15,000 subjects— found no significant differences between those with pain and those without pain. However, women had a higher neck lordosis angle than men, and older adults also tend to have such higher angles than younger adults. And so, it’s not easy to tell who has neck pain or not based on neck posture alone.

- In 2013, a large study in Hirosaki, Japan, also found very little association between the neck curvature and neck pain among 762 men and women in their twenties to eighties.

- A Swiss study in 2006 found no association between the curve of the cervical spine and neck pain among X-rays of 54 subjects with neck pain and 53 without neck pain. The researchers wrote that there was “no significant differences between the pain and no pain groups for either the total curvature or the segmental curvature at any level.”

(Image by Midjourney, illustration by Nick Ng)

- Interestingly, researchers in Quebec, Canada, examined three groups of subjects with acute neck pain, chronic neck pain, and no neck pain. They found that people with huge cervical lordosis have no pain yet chronic neck pain sufferers had the least amount of neck lordosis. Those with acute neck pain are somewhere in between the other groups.

- Similar studies before the age of smartphones also found similar results: in Norway (1985) and Finland (1997, 2004).

With such conflicting messages between what science says vs. what you see online, this led to some researchers to question the prognosis and the relationship between neck posture and pain. They said that there’s a tendency for clinicians to find proper spinal alignment as “appealing,” and thus, they think that’s something they strive for.

“It is surely difficult to find definite answers considering that pain as a biopsychosocial phenomenon is probably too vast a problem to be simply reduced to any kind of measures, no matter how sophisticated and appealing [it] may be,” they wrote.

(Image by Midjourney, illustration by Nick Ng)

What causes forward head posture?

While neck posture is poorly associated with neck pain, some studies indicate other factors that are more likely to cause neck pain rather than structure alone.

A large Australian study in 2016, led by Dr. Karen Richards from Curtin University, found that the slump sitting posture among more than 1,100 17-year-olds, are influenced by:

- body mass index (BMI)

- exercise frequency

- sleep quality

- stress

- depression

Rather than lumping all the subjects into one group, they divided the subjects into four clusters:

- Cluster 1 (“upright”): has the least neck flexion, head protraction, and thoracic kyphosis;

- Cluster 2 (“intermediate”): same as Cluster 1 but with only slightly more thoracic kyphosis;

- Cluster 3 (slumped thorax/forward head): has the highest amount of thoracic kyphosis and forward head posture;

- Cluster 4 (straight thorax/forward head): same as Cluster 1 but with forward head posture.

You’d think that Cluster 3 would have the highest prevalence of neck pain, but the researchers found hardly any differences between neck and upper back posture with pain.

Cluster 3, however, had “higher odds of depressive symptoms.” Cluster 1’s usage of the computer and smartphone was not much different than the other clusters, but this group is more physically active which may contribute to a more upright posture.

“The current results do not support the commonly held clinical and societal belief that [neck pain] is related to spinal posture,” the authors wrote. This is consistent with the findings from previous systematic reviews that found a weak relationship between neck pain and posture.

“This suggests that [neck pain] is associated with changes in pain regulatory mechanisms rather than biomechanics,” Richards et al. wrote. “This supports calls to consider and manage [neck pain] from a broader biopsychosocial perspective.”

They question the posture advice that teenagers and adults often get not only from their doctors but also what they see and hear online.

Take away

There’s probably no harm in trying to reduce your forward head if you worry about how you look or having potential health problems associated with this posture.

But remember that pain isn’t just about your posture. There are psychological, sociological, and environmental factors that influence your neck pain, such as chronic stress, anxiety, lack of sleep, unemployment, your neighbors’ dog, unpaid medical bills.

“[Your head] is designed so you can look forward, to the left, to the right, look up—and yes, look down,” wrote Dr. Bronnie Thomposon, who teaches at the University of Otago in New Zealand on living well with chronic pain.

She pointed out that many of the biomechanical measurements do not account for living tissues and our adaptive brain and nervous system.

“If you hold any muscle in one position for long enough it will probably be uncomfortable,” Thompson wrote. “It’s a good thing to feel uncomfortable not because you’re doing any damage to the area, but because it means you’ll move.”

And any changes to what science suggests about posture and pain would take many years and probably even more studies and data to overturn the existing body of knowledge.

So, you probably shouldn’t worry about fixing your neck posture too much.

Remember that before we have cell phones or color TV, people already have a forward head from reading, drawing, and doing crafts.

Men reading advertisements for jobs on, Melinda Street, Toronto, Canada, in 1919. (Public domain)

A native of San Diego for nearly 40 years, Nick Ng is an editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine, an online publication for manual therapists and the public who want to explore the science behind touch, pain, and exercise, and how to apply that in their hands-on practice or daily lives.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a B.A. in Graphic Communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014.

When he is not writing or reading, you would likely find him weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, or exploring new areas to walk and eat around Southern California.

Hey Nick, awesome inventory and analysis! Great to see so much of it in one place, and well-summarized.

Uncertain about your point on this one: “However, most research finds a lack of strong cause-and-effect relationship between neck posture and neck pain.”

Do you mean you think most research specifically looked for and *found* a *lack* of causal relationship, or *didn’t find* a strong cause and effect relationship (perhaps because it wasn’t there, or was weak, but also perhaps because it wasn’t looked for)?

My own inventory of the research isn’t as exhaustive, but I suspect some combination of the latter, rather than the former.The take-away is likely the same in either case (strength of any causal relationship is weak if any) tho with differing degrees of certainty.

Thanks again