A Missouri school district recently reinstated the use of corporal punishment on children with written consent from a parent after more than 20 years of prohibiting the practice.

The district in Casville, Mo., asserts that corporal punishment, defined as “the use of physical force as a method of correcting student behavior,” is a viable method of changing behavior.

Basically, corporal punishment is another way of saying physical punishment, which encompasses spanking, paddling, flogging, whipping, beating, etc. Many experts in psychology, education, and medicine dispute the idea that painful punishment is effective in correcting children’s behaviors.

Recently, NPR highlighted some of the parental support in the Cassville district alongside warnings about the detrimental effects of the practice from experts. The sentiment among the parents who are in favor of using corporal punishment in schools to change undesirable behaviors seems to be that it’s no big deal.

But years of research has shown that corporal punishment is a big deal and it comes with additional consequences. Children who are raised in households that use physical punishment for discipline may turn to aggressive or hostile behaviors in their own relationships.

This type of discipline can also lead to poor performance on intellectual tasks, depression, or low self-esteem.

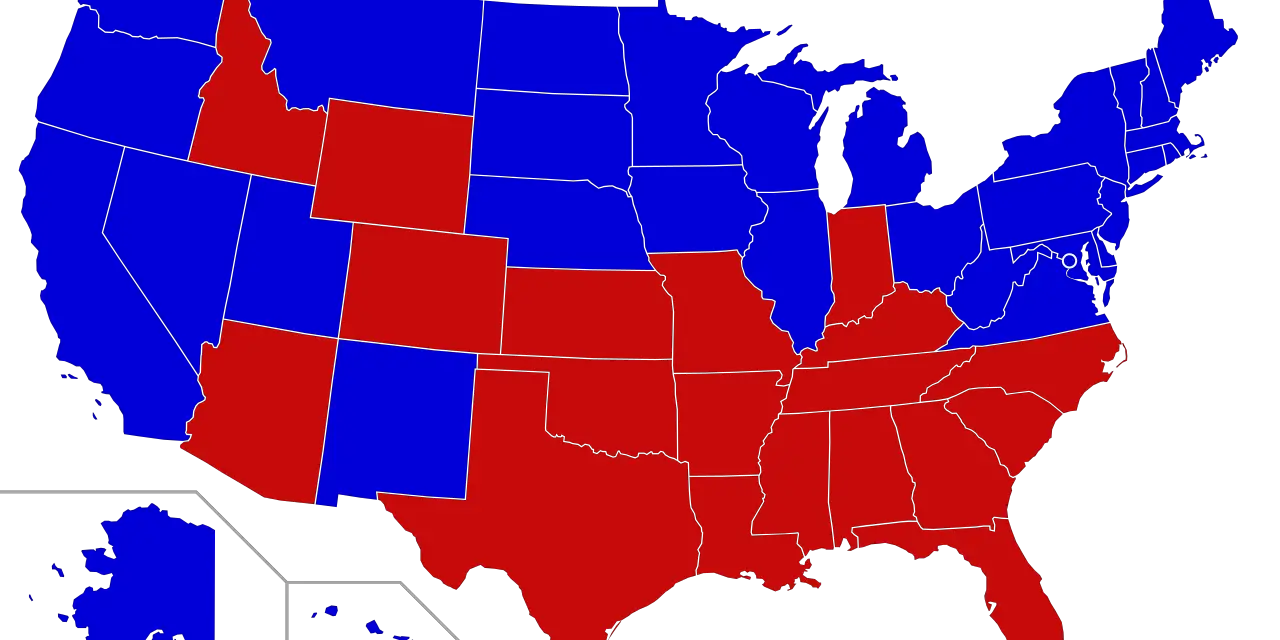

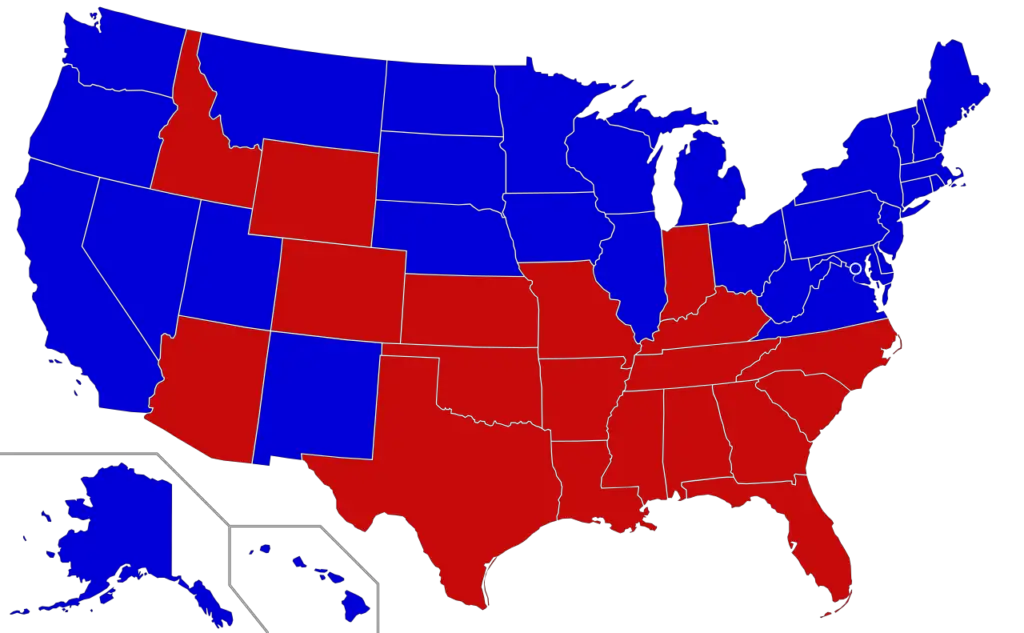

Corporal punishment in public schools is currently practiced in 19 states:

Legality of corporal punishment in the United States. (Image by Theshibboleth, distributed under an the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license (CC BY-SA 3.0).)

About 70,000 children at nearly 4,000 public schools in the U.S. were subjected to corporal punishment in the 2017-2018 school year.

During the 2017-2018 school year, male students were four times more likely to be disciplined by corporal punishment than female students.

Among students with disabilities, males were 10 times more likely than females to be subjected to such punishment.

Overall, the practice occurs more often with white students than Black students, however, when examined by gender, white males and Black females are most involved.

Among students with disabilities, corporal punishment is used twice as often with white students than Black students.

Negative effects of corporal punishment

A 2018 review on the effects of corporal punishment in young children concluded that there are many negative consequences from physical punishment, including:

- abnormalities in brain development

- decreased brain volume by 15% to 20%, particularly on the grey matter

- lack of impulse control and mood regulation

- lack of attention and emotional expression

- lower literacy rates

The researchers considered these findings to be “excessive and unacceptable.”

An earlier review found several psychological and psychiatric effects among kids who were abused, which include precursors to:

- generalized anxiety and panic disorders,

- post-traumatic stress disorder,

- lack of control of aggressive, verbal, and sexual behaviors,

- difficulty with emotional memory

- suicidal ideations,

- attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

Kids and teens who were subjected to corporal punishment tend to develop aggressive behaviors as a response.

A 1977 study showed that young boys who watched a video of a boy being punished for misbehavior then displayed more aggression when playing with dolls than their peers who watched a video of non-violent punishment for the same misbehavior.

In 2013, psychologist Christopher J. Ferguson showed that aggressive behavior wasn’t the only ill-effect of the practice. Children who have been subjected to corporal punishment perform poorly on cognitive tasks that measure things, such as intellectual capacity, aptitude, or achievement.

Ferguson also endorses that there’s no evidence that spanking or corporal punishment has any advantages over alternate means of discipline.

Yet in 2020, a large scale systematic review of corporal punishment in the U.S., Africa, and other countries found that physical punishment continues to be prevalent worldwide and does not seem to be decreasing over time.

The review found associations between corporal punishment and physical, behavioral, academic, and mental health problems in children.

They found that Black males in the U.S. and those who experienced violence at home were the most at risk.

Schools with a mental health professional on staff were less likely to use corporal punishment while children in schools who had teachers that favored physical discipline were more at risk.

Students or schools with lower socioeconomic status were also at increased risk.

Dr. Catherine Ward, a psychology professor at the University of Cape Town in South Africa who worked on the review, advocates for violence prevention at the public health levels.

“[There’s a] widespread acceptance of corporal punishment everywhere in the world, with perhaps the exception of some Scandanavian counties.” she said.

She said that it’s largely because people:

- tend to not have alternatives;

- tend to parent the way we were parented (or teach the way we were taught)

“This is one reason why parenting programmes are recommended as one of seven evidence-based strategies for preventing violence against children,” Ward said.

Dr. Elizabeth Gershoff’s 2002 study is one of the bedrocks of corporal punishment research. She examined 27 included studies and found a positive relationship between physical punishment and childhood aggression. (In this context, ’positive’ means that more punishment leads to more aggression.)

Conversely, among more than 500 parents who were taught to use less physical punishment, children showed less difficult behaviors.

As recently as 2010, about 50% of parents with toddlers and nearly 70% of those with pre-school age children were still using regular corporal punishment to discipline their children.

It’is even more common in middle and high school where 85% of students have been punished by their parents using physical pain.

These statistics are even more alarming considering that the consensus among medical and social scientists is that “risks for substantial harm from corporal punishment outweigh any benefit of immediate child compliance.”

In the 1980s, prior to upgraded human subjects protections, a series of experiments was conducted at Idaho State University to examine the effects of spanking.

In these studies, children with behavioral issues and their parents were put into spank or no-spank groups. The group that did not spank their children used a time-out style intervention.

Across all conditions, even though physical punishment was effective in changing behaviors, it was no better than the time-out strategy.

In short, corporal punishment may make immediate changes but it isn’t better than disciplinary methods that do not have the risk of physical injury or mental health issues. In fact, it can worsen children’s misbehaviors in the long term.

Gershoff’s paper reported that in 13 of 15 studies physical punishment was correlated with less long-term behavior, less moral, and less prosocial behavior, like helping, sharing, comforting, cooperating, etc.

Corporal punishment on chronic pain

Studies on the development of chronic pain following adverse childhood events have found mixed results. While some show a link between trauma and painful conditions such as fibromyalgia, neck and back pain, or migraines, others show no link at all.

A 2009 paper reported on the results of a study that followed children from birth to 45 years old. In this group of more than 7,500 people, researchers found that the risk of developing widespread pain is higher in children who are:

- separated from their mother

- live with household dysfunction

- experience financial hardship by the time they are seven years-old

In a 2019 research of more than 3,000 undergraduate students, 90% of them reported some sort of trauma (general, physical, emotional, or sexual). But the prevalence of chronic pain was only a fraction of that as most reported no chronic pain.

Although childhood adversity wasn’t necessarily predictive of chronic pain in these participants, the number of incidents seems to matter. Those who reported more adverse events were at increased risk for headaches and low back pain.

One of the suggested mechanisms that link negative childhood events and chronic pain is allostatic load. Adverse events trigger the body’s systems to adjust their activity in order to create allostasis, which is the ability to maintain stability through change.

You can think of allostasis as the means by which the body remains in homeostasis, or the state of balance among the body’s systems to survive.

Over time, these adverse events can lead to allostatic overload which is the ‘wear and tear’ that the brain experiences from stress. Overloading the body with stress can lead to harmful reactions from the neurological, immune, cardiovascular, and endocrine systems.

Allostatic load has been associated with severe headache, pain lasting more than 24 hours, and widespread pain.

[Related: How Child Neglect Affects Chronic Pain in Adulthood]

Alternatives to corporal punishment

Policy makers, physicians, parenting coaches, and anyone with influence on the matter should feel confident in encouraging non-violent discipline.

There’s a wide range of alternatives that not only far outweigh the risks of corporal punishment but also create an optimal environment to further child development.

Karen Quail, who is the founder of Peace Discipline in South Africa, recently worked with Ward to do an overview of systematic reviews on non-violent discipline.

They emphasized the need for non-violent options that effectively promote behavior change. It’s important to have several non-violent options that work quickly so that a parent, caregiver, or teacher:

- can match the intervention to the needs of the child

- does not fall back on using physical punishment if the first technique doesn’t work

The overview found more than 50 non-violent options that had positive effects on behavior. Some of the tools include:

- behavior contracts

- communication

- feedback

- modeling

- monitoring

- problem-solving

- reinforcement,

- restorative justice interventions

- self-management

- time-out.

Peace Discipline provides information on the tools and how to implement them for those who are looking to learn about non-violent discipline.

“If you want people to stop, you need to train them in alternatives,” said Karen Quail, founder of Peace Discipline. (Photo courtesy of Karen Quail.)

Possibly the most important finding of this review is the large number long-term positive outcomes associated with the use of non-violent discipline.

Positive outcomes include

- academic achievement

- better self-regulation

- higher self-esteem and independence

- lower rates of depression, suicide, substance abuse problems, crime, risky sexual behaviors, and agression

Quail, who has been working in the field for almost 20 years, described the process as “swimming upstream.” Although corporal punishment is not allowed in schools in her native South Africa, it’s still used and is the norm in homes.

She believes parents and teachers continue to discipline this way because they base their decisions on experience, not evidence. Most were hit themselves as children, so they didn’t grow up with a model of non-violent discipline.

And so, she believes in giving adults who use corporal punishment replacement behaviors just as you would do for children who were misbehaving.

“If you want people to stop, you need to train them in alternatives,” Quail said.

The key to non-violent discipline is attunement, which is a basic building block of attachment between a parent, teacher, or caregiver and the child.

Attunement is the art of matching the response from the adult to the needs of the child—and no one needs physical punishment.

Quail implored that under no circumstance should we be hitting children when there are so many alternatives that lead to positive outcomes.

Dr. Cindy Hovington, founder of Curious Neuron and co-founder of Wondergrade, also works to help parents connect with their children while creating an environment where both the parent and child can thrive.

Hovington agrees with Quail and Ward that most people who practice corporal punishment do so because they don’t know how else to address their child’s behavior.

“What I’m hoping is that parents dig a little deeper and that as a society we begin to look past the child’s behavior and start to focus more on analyzing their environment,” Hovington said. She highlighted some questions parents should ask:

- “Is my child acting out because they don’t feel seen or heard?”

- “Is there someone in their environment that is making them not feel safe?”

- “Are they struggling with a learning disorder and misbehaving in school because of this?”

Hovington believes that we need to break the cycle of behavior problems being treated with physical punishment because the research is clear that this punishment, in turn, leads to more behavior problems. Instead, she encourages parents to show their children that “they are people too and do not deserve to be hit.”

“Some [parents] were raised this way and feel that ‘they turned out okay’ because they have a strong career and are doing well,” Hovington said. “However, the consequences of physical punishment are not about careers. A large part of it is how we learn to cope with emotions.”

And these ways to cope include asking questions like:

- Are we communicating our needs and emotions with our partner?

- Are we struggling with relationships?

- Do we lash out and yell a lot at our kids or adults in our lives?

- Are we internalizing emotions and telling people we are ‘fine’ when in reality we want to explode?

Photo courtesy of Cindy Hovington.

She hopes that by focusing on mental health, emotional regulation, and communication skills in today’s parents, families, and schools, we can help them see that the consequences of physical punishment outweigh the immediate, short-lasting behavior changes.

“We all want our kids to thrive and their childhood has a huge impact on this,” she said.

Ending corporal punishment in schools has a long way to go, but it may take baby steps, distrct by district.

One such district is in Ranchester, Wyoming.

Jeffrey Jones, a principal at Tongue River Middle School, has recently been working to get corporal punishment in schools outlawed in his home state.

He completed his dissertation on the use of corporal punishment in the public schools in Wyomnig and found at least 40 professional organizations that are against corporal punishment, including the National Education Association.

“They’re not against it because they think it is messy or uncomfortable,” Jones told the Sheridan Press. “They are against it because there are mountains of evidence that shows it harms kids.”

Echoing the sentiments of Hovington, Quail, and many researchers, Jones encouraged educators to lead by example in building positive relationships with kids where they are seen as human first.

[Related: Pediatric Pain: How Parents Pass Their Pain to Their Children]

Penny Goldberg, DPT, ATC

Penny Goldberg, DPT, ATC earned her doctorate in Physical Therapy from the University of Saint Augustine and completed a credentialed sports residency at the University of Florida. She is a Board Certified Clinical Specialist in Sports Physical Therapy.

Penny holds a B.S. in Kinesiology and a M.A. in Physical Education from San Diego State University. She has served as an Athletic Trainer at USD, CSUN, and Butler University.

She has presented on Kinesiophobia and differential diagnosis in complicated cases. Penny has published on returning to sports after ACL reconstruction and fear of movement and re-injury.

Outside of the clinic, Penny enjoys traveling, good cooking with great wine, concerts, working out and playing with her dogs.