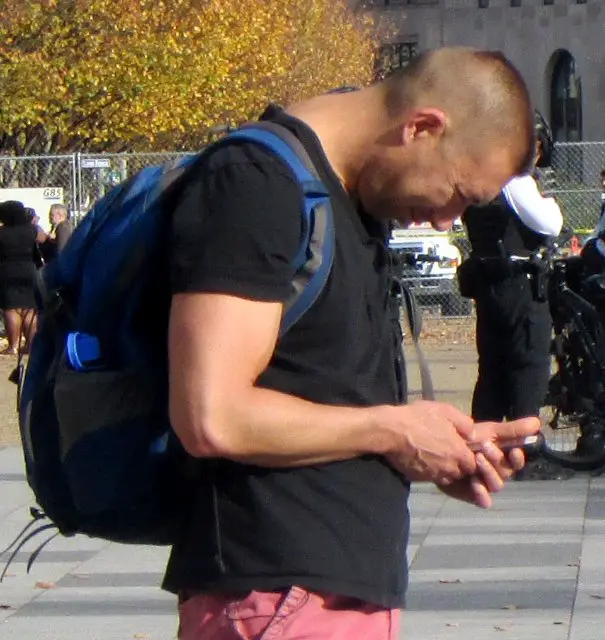

Text neck is a repetitive stress injury to your neck where your hang or flex your neck in a forward position while looking at your phone or similar devices for a long time. Symptoms include having a forward head, hunched shoulders, and a rounded upper back, which makes many clinicians believe that this posture is a primary cause of back, neck, and shoulder pain.

Many news reports throughout the 2010s demonized text neck to cause other problems, such as producing ‘horns’ in the back of the skull, causing nerve damage in the cervical spine, and weakening muscles in the anterior neck and chest. Some clinicians even advertise on social media that they can “fix” your text neck.

Text neck was first coined in 2012 by a U.S. chiropractor Dean L. Fishman, but the term didn’t get mass media attention until 2014 after a U.S. physician, Kenneth Hansraj, published a paper that year. Even though his paper had major problems in how it was set up (e.g. lack of explanation on how the experiment was done), it helped fuel the popular idea that posture is a strong cause of joint pain. (Your neck might be rolling its eyes at the hype.)

However, research in the relationship between posture and pain suggests that text neck and neck curvature are not a reliable indicator for neck or back pain. Here’s why.

So what does science say about text neck and pain?

Your neck can withstand a tremendous amount of sustained pressure at different angles. A team of researchers from the University of Bristol examined how much pressure can the human cervical spine withstand in various directions and angles.

Based on 22 cadavers from elderly subjects, they found that the neck can withstand nearly 2.4 kilonewtons—jor nearly 540 pounds—of compressive force before reaching its breaking point. That’s nine times more force than Dr. Hansraj’s “60 pounds.”

Age

Although these researchers noted that dead bodies do not always apply well to living people, they think that living tissues are likely able to resist and adapt to higher load. Thus, our neck is a lot more robust than some of us believe.

More than 12 years of scientific evidence found weak associations between neck posture and pain in the neck and back. For example, a 2019 systematic review found that age is a significant factor in predicting who is likely to have neck pain, not posture. Researchers it that review examined 13 studies and found a “significant difference of forward head posture between adults with and without pain and a significant association between forward head posture and neck pain in adults.”

In other words, teenagers with text neck are less likely to have neck pain than adults with text neck, except for those teens with a “lifetime prevalence and number of doctor visits.” The study does not indicate a cause-and-effect relationship between posture and pain, and it’s possible that a forward head posture (and rounded shoulders) could be an adaptation or response to pain.

X-rays and scans

Not even X-rays and scans alone can tell whether someone has pain or had a previous injury based on looking at the neck shape.

- A 2007 Swiss study found no strong correlation between the lack of a lordotic curve and neck pain among 107 adults. After researchers analyzed X-rays of the neck and measured the subjects’ curvature, they found that patients with normal or a flatter neck had neck pain in various degrees. Likewise, they found that subjects with no neck pain also had normal or no curves in their neck.

- A large Japanese study from also found very little association between neck curvature and neck pain among 762 adults between their twenties and eighties. “We found no association between the sagittal alignment of C2–C7 and neck symptoms in males or females after adjusting for age,” the authors stated.

- Among high school students, a 2016 Australian cross-sectional study of more than 1,100 17-year-olds found no association between neck curvature and neck pain.

However, they noted that students both a slumped posture and a foward head “had higher odds of depressive symptoms,” which was consistent with a previous research that found teens with slumped postures had higher association with depression and anxiety. The students with a more “upright” posture also had similar amounts of phone and computer usage, but they were more physically active than the other groups.

“The current results do not support the commonly held clinical and societal belief that [neck pain] is related to spinal posture,” the authors said. “This is consistent with findings from systematic reviews that the association between [neck pain] and posture is weak.”

They also acknowledged genetics and psychosocial factors that contribute to neck pain, such as being female, depression, stress, and poor sleep patterns.

“This suggests that [neck pain] is associated with changes in pain regulatory mechanisms rather than biomechanics,” the authors concluded. “Despite strong support for the existence of neck posture subgroups, they were not associated with [persistent neck pain], [neck pain] in sitting or headaches in 17-year-olds. This raises questions regarding the efficacy of generic postural advice for adolescents with and without [neck pain].”

What about the studies that says text neck causes neck pain?

“Cause” can be a loaded word when it comes to determining X causes Y because this type of thinking can make you overlook other potential causes of your neck pain. While are a few studies that concluded text neck is associated with neck pain, they just show an association or correlation, not causation.

For example, a 2014 Portuguese study stated, “68% and 58% of the adolescents revealed anteriorization of the head and protraction of the shoulder, respectively. The subjects with neck pain had a more forward head posture. Gender was also found to have an important effect on posture and neck pain, with girls revealing a lower cervical angle and more neck pain.”

If you accept the conclusion at face value and skip how the study was done, we misguide ourselves into thinking that neck posture matters a lot. Again, this study only suggests an association, not causation. The researchers were only examining students with neck pain. Without a control group, you cannot make an positive association between neck posture and pain.

Another study from Tehran, Iran, compared symptomatic and asymptomatic office workers. They found asymptomatic workers spent fewer hours working at a computer than their symptomatic coworkers, and those with neck pain had “a poorer posture of cervical and thoracic spine during working time.”

While this may indicate that there is a relevant association between posture and pain, we don’t know whether the subjects’ pain is caused by forward head posture or the posture is a result of pain adaptation. The authors acknowledged that there are stress and other psychological factors may contribute to symptomatic workers due to workload and longer hours at the computer.

“The problem with text-neck is the same problem as any other prolonged position. We are meant to move. If you hold your head in ANY position for prolonged periods it is likely that you will feel pain. Ask a soldier on parade. That ideal upright position is a real pain in the neck..” ~ Gregory Lehman

So how do I ‘fix’ text neck?

While you don’t really need to do anything to “fix” it, there are simple exercises that you can do to alleviate the stiffness and pain. For each exercise, hold each position for about 1–2 seconds, and repeat 4–5 times.

Nod your head

Gradually tilt your head back to look up and then look down.

Look both ways

Turn your head as far as you can to your right, and turn your head to your left.

Side to side

Tilt your head to your right to bring your right ear toward your right shoulder without shrugging your shoulders like you are looking for a book at a library shelf. Then tilt your head to left.

Neck pain existed before smartphones

Keep in mind that people had neck pain and “text neck” before smartphones were invented. Even back then, researchers failed to find a strong relationship between neck posture and neck pain.

Neck pain among teens

A 1997 study of more than 1,600 schoolchildren found that about half of them who had pain at least once a week had the same pain a year later. Mikkelsson et al. found that girls had higher prevalence of neck, upper back, and chest pain than boys. Follow-up studies were made in 2004 and 2007 and found similar results. While these studies did not examine posture and other biomechanical factors, they mentioned that parents could impact how their children think about pain, such as the belief that pain “runs in the family.”

The researchers considered their study’s follow-up time to be too short because they cited another study from Norway in 1985 that followed up schoolchildren nine to twelve years later. In that research, muscle tenderness and tension were risk factors for developing neck pain among 9% of the 302 students.

Even among 18 of these students who had thoracic kyphosis and muscular tension, these conditions did not add more risk of cervical pain. “This study does not give definite evidence that posture deviations are risk factors for cervical pain,” the authors wrote. Instead, they cited that psychological factors, such as negative self-image, are more likely to be higher reinforcements to persistent neck pain, especially among those who frequently visited a physiotherapist or chiropractor regularly for treatment.

Muscle strength and neck pain

A 2004 study on neck pain among 169 female office workers in Finland found that neck muscle strength testing “may not be reliable for the measurement of maximal neck strength in patients with neck pain, but they may be useful in showing how much the function of painful muscles is reduced under strain.”

The researchers also found that subjects with chronic neck pain had quite a large variety range of motion during passive neck flexibility test, indicating that range of motion is not a reliable factor in determining who has neck pain and why. They suggested that neck pain rehab should help patients increase pain threshold during strain in the neck.

Related: Do Heavy Backpacks Cause Back Pain in Children?

Pain stems from many factors other than ‘text neck’

“Pain is the output. Nociception is one of the inputs. All of the inputs are evaluated when we’re talking about pain, I think, according to this question: How dangerous is this? Based on everything I know, which is all of the information available to me right now, how dangerous is this really?” ~ Dr. Lorimer Moseley

Research in the last 100-plus years reveals that pain is much more complex than just “poor posture.” Given the vast research and weight of evidence that pain is a sum of psychosocial factors, how we feel and react to pain depends on these interactions. Sometimes one factor contributes to pain higher than others under certain circumstances.

For example, in a large study in 2013 of more than 3,900 individual twins in Finland, the researchers found that genetics and specific environmental factors can contribute to the likelihood of pre-teens (and likely later in life) to get persistent neck pain, at least among twins.

While there was no significant difference between genders, individual twins who grew up in different households are more likely to get neck pain than those who grew up in the same household. In this case, social and environmental factors have an impact on their psychology and biology.

Bottom line

People have been engaging in the ancient art of looking down for centuries, well before smartphones waltzed into our lives. Whether it’s reading a book, writing a letter, or contemplating the meaning of life (or just staring at your shoes), the downward gaze is nothing new. Blaming all our neck-related problems on smartphones and computers might be a tad dramatic.

“Back in the Dark Ages before cell phones and earpieces existed, office workers were prone to sore necks and shoulders from holding the phone on one shoulder,” Laura Allen said, who is a licensed massage therapist and educator from Gilkey, North Carolina. “The truth is people have been working [with text neck] for centuries: jewelry makers, seamstresses, surgeons, assembly line workers. They all work looking forward and downward. It’s just an old thing with a new name, and not necessarily responsible for someone’s neck pain. We shouldn’t be too quick to jump on the latest fad injury bandwagon just because it’s a popular phrase.”

A native of San Diego for nearly 40 years, Nick Ng is an editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine, an online publication for manual therapists and the public who want to explore the science behind touch, pain, and exercise, and how to apply that in their hands-on practice or daily lives.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a B.A. in Graphic Communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014.

When he is not writing or reading, you would likely find him weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, or exploring new areas to walk and eat around Southern California.