A frozen shoulder, also known as adhesive capsulitis, is a condition characterized by stiffness, pain, and restricted movement in the shoulder joint. It typically develops gradually in four stages: the painful stage, the freezing stage, the frozen stage, and the thawing stage. These four stages can last from six months to two years or more. The exact cause is unclear, but it’s more common in people with certain medical conditions like diabetes.

Although the cause of a frozen shoulder is not well understood, progress in pain research can help steer clinicians and patients to find the best treatment possible without wasting their time on less effective or ineffective treatments.

Prevalence

Frozen shoulders tend to occur among those who are over age 40 and is uncommon among teenagers and young adults. Women tend to be more likely to get frozen shoulders than men. While some research estimates about 2% to 5% of most developed nations’ population has a frozen shoulder, the numbers can vary among more specific populations.

For example, about 8% to 10% of the population in the U.K. has a frozen shoulder while 15.6% of more than 800 Asian Americans (mostly of Japanese descent) has it. In Japan and China, it is commonly called a “50-year-old shoulder.”

Frozen shoulder anatomy

The shoulder is made up the glenohumeral joint (ball-and-socket joint), the acromioclavicular joint (acromion attaches to the clavicle or collarbone), and the sternoclavicular joint (clavicle attaches to the sternum). The head of the upper arm bone (humerus) attaches to the glenoid fossa, a shallow cavity of the shoulder blade. Strong fibrous connective tissues keep the shoulder in place while allowing it to move freely in all directions.

Shoulder muscles that move the shoulder joint include the rotator cuffs (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, subscapularis), teres major, deltoids, trapezius, rhomboids, pectoralis major and minor, upper arm muscles, and neck muscles. Various ligaments and tendons attach the bones to these muscles or other bones.

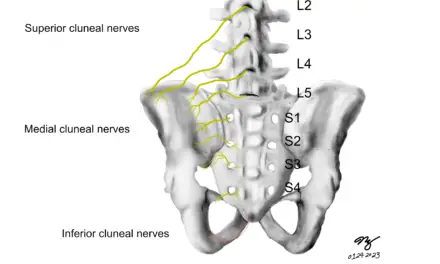

Nerves that innervate the shoulders originate from the brachial plexus, a bundle of nerves that stem from the C5 to T1 of the spine. These nerves go through between the front and mid scalene muscles that are in the back of the neck, and branch off to different shoulder muscles.

In frozen shoulders, the anatomical focus would be primarily in the shoulder capsule and the glenohumeral joint as well as examining pain on a broader scale.

Frozen shoulder stages

The most common symptom of a frozen shoulder is the gradual onset of pain, “freezing,” “frozen,” and “thawing” stages. Contracture of the shoulder capsule—the gradual hardening or shortening of the connective tissues within and around the structure—is another common symptom. The duration of each stage varies among individuals, and it is difficult to predict how long it lasts.

There are four common stages of a frozen shoulder: pain, freezing, frozen, and thawing.

- Pain stage: Marked by pain and a gradual loss of movement. During this stage, there is swelling and increased blood flow in the joint lining, but the tissue around the joint looks normal.

- Freezing stage: Symptoms gradually worsens over three to nine months, and there is inflammation around blood vessels and collagen buildup. Daily tasks, such as putting on clothes and reaching behind your back gets more difficult.

- Frozen stage: Pain gradually reduces but the shoulder becomes stiff and almost immobile. The affected shoulder would round forward, causing one side of your torso to turn forward. This phase lasts between nine to 18 months.

- Thawing stage: Shoulder gradually returns to normal function. However, this can last between one to two years, rarely more than that.

An early study in 1975 found that about half of the 49 patients studied never had full recovery of their shoulder range of motion. Only three patients had a life-long handicap of the shoulder. Interestingly, the researcher found very few “defects” in the rotator cuff muscles among all of the patients regardless of the duration of the recovery.

Simplified graph of the frozen shoulder stages.

Frozen shoulder symptoms

Common symptoms of a frozen shoulder include:

- Persistent shoulder pain

- Stiffness in the shoulder joint

- Difficulty moving the shoulder

- Limited range of motion

- Pain that worsens at night

- Difficulty performing daily activities that involve shoulder movement

- Deep ache in various areas of the shoulder

- Referred pain to the deltoid origin and radiates to the biceps

In some cases, frozen shoulder symptoms may manifest in specific areas.

Coracoid process

A study in 2010 found that about 96% of the 85 patients with early stages of frozen shoulder had symptoms at the coracoid process, which is hook-like or beak-like bony projection coming off the shoulder blade towards the front. You could feel it by tracing your finger from the middle of your collarbone to its edge toward the upper arm where the collarbone ends. That is approximately where most of the symptoms occur.

Frozen shoulder movement

Both active and passive range of motion is lost among frozen shoulder patients, and pain tends to worsen when the shoulder capsule is stretched, especially during the freezing stage. Overall, about 80% of all range of motion of the shoulder joint is lost, particularly in shoulder extension (when you put on a jacket) and horizontal adduction (lifting your arms away from your body like you are forming the letter T).

In 2003, a study looked at 10 middle-aged people (nine women and one man) with frozen shoulders. The authors warned that how much the shoulder could rotate inward and outward depended on its position, like whether it was moved closer or farther away from the body.

“The results raise questions about the validity of a theorized single capsular pattern of motion in these subjects,” they wrote.

Illustration of frozen shoulder.

Frozen shoulder causes

No one really knows for sure what are the main causes of frozen shoulders, but some risk factors include:

- Diabetes

- Obesity

- Cardiovascular disease

- Metabolic syndrome

- Various types of neurodegeneration

Hypothetically, these chronic conditions are associated with the dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system that may trigger various physiological conditions that lead to a frozen shoulder.

Physiology

What is known about the “freezing” stage is that there’s a lack or slow down of turnovers of the extracellular matrix (ECM) of the joint capsule. The ECM consists of proteins and connective tissues that serve as “scaffolds” of a cell. It’s also where cues are sent to cells and tissues to proliferate, differentiate, migrate, self-destruct, and a host of other functions. The ECM constantly undergoes remodeling, which is regulated by fibroblasts and a broad family of enzymes called metalloproteinases.

One kind of metalloproteinase is called matrix metalloproteinase (MMP), which breaks down collagen in the joint capsule, while another kind—called tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP) blocks MMP’s actions, as the name implies. Evidence in a 2013 Indonesian study found that two types of MMP levels were “significantly lower” and TIMP levels were higher among frozen shoulder patients than healthy patients. Thus, an imbalance of these enzymes may be a major contributor to a frozen shoulder. Many factors may instigate this process, but there has been almost no strong evidence that indicates a causal relationship.

Inflammation of the synovial joint of the shoulder is another common symptom, which can contribute to pain if the shoulder is moved actively or passively. The thickening and contracture of the anterior shoulder capsule, particularly in the middle of the glenohumeral ligament and coracohumeral ligament, reduces the volume of the shoulder joint, which reduces shoulder movements and mobility.

Low-grade systemic inflammation and stress

There is some evidence that low-grade inflammation that stays with you for many years can be a strong predictor of getting a frozen shoulder, but no causality of this relationship has been established. Physiotherapist and researcher Max Pietrzak from the University of Bath stated that such chronic inflammation is “strongly associated with upregulation” of several types of cytokines (broad category of proteins that modulate cell communication and immune function) among patients with a frozen shoulder.

Chronic inflammation may develop from acute stress that somehow becomes chronic. No one knows why some people can recover from acute stress while others do not, but it’s understood that depression, child abuse, work burnout and work-related stress, and similar factors determine how some people respond to acute stress.

“Individual differences in one-time stress exposure are only one potential pathway from stress to disease,” Dr. Nicholas Rohleder reported in a 2018 paper. “In real life, humans are exposed to repeated stressful events, some of different and varying nature and others recurring and largely similar. It has been proposed that an adaptive way to respond to repeated exposures to the same stressful stimuli is to habituate, that is, to show lower psychosocial and biological responses to re-exposure.”

Metabolic syndrome

Pietrzak described metabolic syndrome as having too much abdominal fat tissue, having higher-than-normal levels of triglycerides, high blood pressure and fasting blood glucose, and low levels of the “good” cholesterol. He speculated that because frozen shoulders occur more frequently among older adults, metabolic syndrome and chronic inflammation may have the same underlying causes.

One study by Gumina et al. found that a majority of their 56 sample subjects had most of these metabolic conditions during the freezing stage. About 23% had high blood glucose, 64% had high “bad” cholesterol, 43% had high triglycerides, and 68% had high total blood cholesterol.

Diabetic frozen shoulder

Diabetics have at least a 10% to 30% chance of having a frozen shoulder, compared to 2% to 5% of the general population. The higher the number of hemoglobin A1c, the higher the chances of getting a frozen shoulder.

A 2023 meta-analysis of eight studies with a total of more than 346,000 people found that diabetics are nearly four times more likely to develop frozen shoulders than non-diabetics. However, the researchers cautioned that the studies didn’t properly account for other factors that could affect the results. All eight studies were considered to have a high risk of not considering all the factors that could influence the outcomes.

In each study, these factors were either not considered at all or the statistical methods used weren’t appropriate, which aren’t good for understanding the causes of diseases. So, these studies might have missed important factors or mistakenly adjusted for things like stroke.

One retrospective study by Chan et al. reviewed more than 24,000 patients with this type of hemoglobin and found that for every hemoglobin A1c level that is more than 7, there is an increased risk of 2.77% of getting a frozen shoulder.

Hypothyroidism

Some research shows that pathology of the thyroid gland has a fairly strong association with frozen shoulders, particularly hypothyroidism. A 2020 Brazilian study compared the thyroid health and many health factors of 166 patients with a frozen shoulder with 126 patients who were diagnosed with rotator cuff tears and a control group of 251 subjects with no existing shoulder pain or problems. The researchers found that hypothyroidism and “benign nodules” on the gland are strongly associated with frozen shoulders.

About 17% of the patients in the frozen shoulder group had hypothyroidism and 10% had benign nodules, while the other two groups had 4% and 2% in the rotator cuff tears group and 8% and 2% in the control group.

While this finding does not mean having these conditions cause frozen shoulders, the study’s results are similar to previous research in Shanghai (China), Jerusalem (Israel), and Antalya (Turkey) on various thyroid problems with frozen shoulders. Thus, it’s likely a combination of several physiological factors may lead to frozen shoulders.

Hyperthyroidism

Hyperthyroidism may also be another strong predictor of getting a frozen shoulder. A Taiwanese study of 4,472 patients in Taipei found that 162 of them had a frozen shoulder. When compared to other diseases, such as diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension, they found that those with hyperthyroidism had 1.22 times the risk of getting a frozen shoulder compared to the general population of Taiwan.

Stroke

Having a stroke may increase the risk of getting frozen shoulders.

About 16% to 72% of stroke patients get shoulder pain on one side, and up to 80% of such patients have no voluntary control of their affected shoulder.

A 2013 study of 106 stroke patients in Nanjing, China, found that frozen shoulders (and complex regional pain syndrome) tend to start in one to three months post-stroke, while centralized pain begins after three months.

Sometimes having a frozen shoulder may increase the risk of getting a stroke. A Taiwanese study of 575 frozen shoulder patients compared this group with 1,201 control patients. The researchers found that the frozen shoulder group had nearly 1.5 times the likelihood of getting a stroke than the control group. Psychosocial factors, such low socioeconomic status, living in rural areas, being female, sleep deprivation, and sedentary lifestyle can also contribute to development of a frozen shoulder.

Parkinson’s disease

Parkinson’s disease is a progressive nervous system disorder that affects movement, often characterized by tremors, stiffness, and difficulty with balance and coordination. This is caused by the degeneration of neurons in the brain that produces dopamine, a neurotransmitter that is necessary for generating movement and coordination.

Although some studies have shown that people with Parkinson’s disease are more likely to have a frozen shoulder, there is uncertainty about the causal relationship.

Papalia et al. in 2018 hypothesized that there may be a “causative loop” between shoulder stiffness and postural change of the shoulder that leads to inflammation and pain, which recycles back to the stiffness and protectiveness. This is partially based on the researchers’ clinical observations and experience where their patients who had shoulder pain and stiffness “were subsequently diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease.”

Because there’s a lack of clinical studies, they cannot confirm the validity of their hypothesis.

Cardiovascular disease

There is limited evidence that finds a relationship between frozen shoulders and cardiovascular disease. Researchers in Tlalpan, Mexico, reported in 1994 that in a seven-year-period, five women and two men came to their hospital for persistent shoulder pain at the upper arm after they had a cardiac catheterization. They had limited shoulder movement, and four of them had diabetes. Considering that the hospital performs about 125 cardiac catheterizations in the upper arm per year, the researchers reported, such frozen shoulder incidences are “rare.”

Boyle-Walker et al. also found that heart disease and circulatory disease are more prevalent among 32 patients with frozen shoulders, along with diabetes and thyroid disease. The patients were compared with 31 people in the control group. However, they emphasize that their study “does not prove cause and effect.”

A 2000 study of 214 male patients who had a heart surgery at a Veteran’s hospital found that 35 patients reported shoulder pain and seven of them (3.3%) had adhesive capsulitis.

Since chronic low-grade inflammation is one of the primary factors of getting a frozen shoulder, perhaps cardiovascular diseases should be taken into consideration as a risk factor.

Physical trauma

Broken bones in the shoulder, shoulder dislocation, and other injuries to the joint may contribute to getting a frozen shoulder, but the evidence about it is scarce. A German study published in 1982 described several types of shoulder fractures and injuries among patients with symptoms of a frozen shoulder. Like other factors, there’s no established causal relationship between physical trauma and frozen shoulders, and the latter may develop independently from the injury, according to the authors.

Infection

A group of bacteria called Propionibacterium acnes may contribute to the development of frozen shoulders. A pilot of study published in 2014 found that 8 out 10 patients had this bacteria in their joint capsule tissues. Six of these bacteria cultures were P. acnes. The researchers failed to find a relationship between the bacteria and frozen shoulder.

Researchers Bunker et al. postulated that the bacteria could get into the shoulder capsule from the gum and teeth and into the bloodstream via the digestive system. “It is possible that frozen shoulders are more common in diabetics because of their reduced resistance to infection. And it is also possible that the reason frozen shoulder never recurs is a result of acquired immunity,” they wrote.

While these bacteria normally inhabit the sebum of the hair follicles just under the skin, it’s possible that these bacteria can get into the shoulder capsule after getting a shoulder injection. However, some ree2search fails to find such a relationship.

Posture

As mentioned in the Parkinson’s disease section, the posture of the shoulder that most people with Parkinson’s have may be part of the hypothetical cycle of the frozen shoulder. But for those without the disease, how much does posture matter in contributing to frozen shoulders?

Some may think kyphosis or rounded shoulders can cause a frozen shoulder or other types of shoulder pain, but the current evidence does not support this idea. A 2016 systematic review of ten studies found that “thoracic kyphosis may not be an important contributor to the development of shoulder pain,” but it’s likely that it reduces the shoulders’ range of motion like the ability to scratch your upper back.

“Even if the studies had reported significant differences in thoracic kyphosis between groups, it would not have been possible to establish whether the thoracic hyperkyphosis preceded the shoulder symptoms or if the thoracic hyperkyphosis was a postural adaptation to shoulder pain,” Barrett et al. stated.

Given the overwhelming evidence mentioned in the scientific literature, frozen shoulder is more likely a physiological disorder rather than a biomechanical one.

Related: Do Different Types of Postures Causes Back Pain?

Prognosis of frozen shoulder

A 2016 systematic review on the prognosis of frozen shoulder concluded that there is enough evidence for clinicians to reliably predict the course of a frozen shoulder based on physical examination and patients’ symptoms, based on seven qualified studies. Patients with chronic frozen shoulders who also have diabetes or frozen shoulders on both sides should consider surgery as an early intervention.

The researchers reported the shortest average duration of a frozen shoulder is 15 months and the longest time is 30 months. About 70% to 90% of patients usually “respond well” to non-surgical treatments.

The drawback with this review is that the bias level of the studies are inconsistent with different studies reporting different treatment protocols, lack of patients’ activity level documentation, and the length of the follow-up period.

Because the natural course of frozen shoulder has not been studied extensively, the researchers concluded that “it is difficult to carry out a high-quality systematic review of this issue.”

Diagnosis of frozen shoulder

Physicians and physical therapists would likely use a differential diagnosis for frozen shoulder, which is a way to compare two or more conditions that may be mistaken for one another. For example, frozen shoulders share some symptoms as shoulder tendonitis, shoulder impingement, and other types of shoulder pain.

They would first review your medical history and may allow you to share your experience with your frozen shoulder. They would also do two types of shoulder range of motion tests: passive and active. If you have pain during a passive range of motion test, where the clinician moves your arm for you, then it’s likely a sign of a frozen shoulder.

One active range of motion tests is the painful arc test, where you stand or sit and move your arms at your sides. Then you gradually raise your arms up to your sides like you are making a snow angel. Pain between 60 degrees and 120 degrees is usually a positive sign of a frozen shoulder.

Clinicians may also use imaging, such as an X-ray and ultrasound, to see your shoulder for any signs of injury or disease and to make sure that you do not have other factors that may contribute to your shoulder pain.

Frozen shoulder treatment

Treatment should aim for decreasing pain and improving range of motion. It should also be individualized since everyone has a different medical history and narrative behind their pain.

Injections

Corticosteroid injections are a common treatment for the early stage of frozen shoulder that provide short-term pain relief. While there are numerous trials and systematic reviews that examined this topic, the evidence indicates that pain relief is mostly short term like oral medications.

However, such injections may not be better than having no injections at all.

In a study of 122 frozen shoulder patients who received an injection to the shoulder joint capsule, combined joint capsule and interval injections, or sham injection, the researchers found no difference in pain relief in the treatment groups. Pain reduction was significant at six weeks, and the relief lasted up to 12 weeks but not at 26 weeks.

Painkillers

Medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may be used to initially control the pain, especially if it disturbs sleep. There are no randomized controlled trials to examine the effects of NSAIDs for frozen shoulders and have no effect on the natural course of the condition.

Oral corticosteroids also have been shown to have short-term pain relief and allow a bit more shoulder movement, according to a 2006 systematic review of five trials with a total of 179 patients. Three of the trials, which are ranked high quality, do not find long-term benefits beyond six weeks.

Calcitonin is another medication, usually taken as a nasal spray, that may alleviate the inflammatory symptoms of frozen shoulders. A South Korean story reported that nasal calcitonin treatment for six weeks had a “notable” improvement than the placebo group. Both groups were given physical therapy treatment during the trial.

Heat or cold treatments

There’s very little evidence for how well heat or cold therapies work for frozen shoulders. A 2008 study from Hong Kong found some benefit to heat therapy with stretching to the shoulder joint’s range of motion (except for shoulder flexion), but the heating group’s outcome is not significantly better than the stretching-only group.

For cold therapy, there appears to be not much difference between that with NSAIDs, injections, mobilization with physical therapy, and no treatment, according to a 1984 study. An earlier study in 1976 found that ice therapy could “shorten” the painful freezing stage of frozen shoulders, but it’s no better than physical therapy alone.

Exercises

A 2014 Cochrane Review found that exercise, when used with manual therapy, does not have better outcomes than corticosteroid injections in the short term for pain relief and better shoulder movement. “It is unclear whether a combination of manual therapy, exercise and electrotherapy is an effective adjunct to glucocorticoid injection or oral NSAID,” the authors wrote.

Even so, they found that manual therapy and exercise “may provide greater patient-reported treatment success and active range of motion.” But self-reported success does not necessarily mean that their frozen shoulder pain has improved.

Nutrition and diet

Because frozen shoulders are mostly a physiological issue and have ties with metabolic syndrome, it is likely that nutrition may play a role in managing the symptoms. However, there’s no existing evidence that any kind of diet could reduce the symptoms of a frozen shoulder.

Surgery and manipulations

Surgery and manual manipulation is usually recommended for frozen shoulders if conservative treatments do not bring any pain relief. It is up to you and your physician or physical therapist to determine the risks versus benefits of surgery.

Manipulation under anesthesia (MUA)

MUA is where a manual therapist stretches your shoulder or moves it in a way that tears and loosens the fibrous tissues in the joint capsule while you are under general anesthesia. Although there’s no established timeline for MUA treatment, Finnish researchers Vastamäki et al. suggested it for those with the condition between six to nine months after the onset of a frozen shoulder. However, current evidence suggests that MUA is no better than corticosteroid injections and hydrodilation “at best.”

Risks of MUA include bone fractures and tearing of the shoulder tendons and labrum.

Arthroscopic capsular release (ACR)

This type of surgery is the most commonly used for frozen shoulder surgical treatment, due to improvements of arthroscopic technology. It allows the surgeon to see what is going on in the shoulder joint capsule. Current studies suggest that ACR has positive long-term outcomes for both pain relief and shoulder movement. One Australian study in 2012 confirmed success of ACR among 43 patients during a seven-year follow-up. The affected shoulders were “comparable” to the healthy shoulders.

The primary risk for ACR is that there is a small chance of damage to the axillary nerve.

(Do not substitute this article for your doctor’s advice and care or to self-treat. This is for information only.)

Massage for frozen shoulders

Although there is a lack of evidence that shows the effects of massage therapy on frozen shoulders, massage may alleviate its symptoms in the short run. A South Korean systematic review assessed whether massage has any short-term or long-term effects for general shoulder pain. Among the 15 qualified studies in the review, the researcher found that “effect size of short-term efficacy was large and robust, thereby supporting the hypothesis that massage is an effective treatment for reducing shoulder pain.” There is no evidence of long-term benefits.

However, the effect size of massage therapy is not significantly different from other types of treatment, such as physical therapy, acupuncture, and rest, Yeon reported. She also pointed out limitations of this systematic review, such as small sample sizes, mixed types of massage, and short follow-ups.

Since touch itself has been shown to modulate pain, it’s no surprise that massage therapy can temporarily alleviate the symptoms of frozen shoulders. Although massage cannot break the connective tissues that limit movement in the shoulder joint capsule (and it is also outside of most massage therapists’ scope of practice), it may reduce the anxiety and depression that often accompany a frozen shoulder.

Almost any type of massage would help alleviate shoulder pain as long as the therapist does not exacerbate your pain. Find what works for you and give feedback to your therapist about pressure and quality of touch. Even if massage therapy offers short-term relief, a few nights of uninterrupted sleep could mean a lot for those with persistent frozen shoulder pain.

Further reading

Massage for Joint Pain: a Biopsychosocial Approach

A native of San Diego for nearly 40 years, Nick Ng is an editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine, an online publication for manual therapists and the public who want to explore the science behind touch, pain, and exercise, and how to apply that in their hands-on practice or daily lives.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a B.A. in Graphic Communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014.

When he is not writing or reading, you would likely find him weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, or exploring new areas to walk and eat around Southern California.