A recent systematic review published in Manual Therapy did not find a strong association between the curvature of the thoracic spine and shoulder pain — or more specifically subacromial pain syndrome (SAPS) — based on ten studies. This condition is described as a “non-traumatic shoulder pain, localised around the acromion, which worsens during or subsequent to lifting the arm.” However, SAPS is a broad term that encompasses shoulder bursitis, subacromial impingement, and rotator cuff tendinopathy. (1)

Although the review did not find any studies that examine the relationship between thoracic curvature and shoulder function, researchers from the University of Limerick in Ireland found strong evidence that less hunching increases the shoulders’ range of motion, including flexion, abduction, and external rotation. In other words, having a more upright posture allows greater freedom of movement, such as reaching higher to the shelf or throwing a baseball with better speed and accuracy. However, Barrett et al. added that some studies that involve various extremes of posture and duration in sitting (n=3) “may not reflect how people move in a real life scenario” because they are based on extreme examples of sitting.

In term of upper back curvature and shoulder pain, they found “moderate evidence of no association between increased thoracic kyphosis and shoulder pain.” Out of the ten studies, four had a low risk of bias, three had moderate risk, and three had high risk.

Those that had a low risk of bias measured kyphosis objectively, had reported all of the intended outcomes and had no loss of follow-up, while those that had high risk of bias did not report their conflicts of interest, did not blind the assessors, and did not reach statistical power. However, the researcher added that there the evidence is limited because all eligible studies in the review were either “cross-sectional studies or involved repeated-measures on a single day.

“Even if the studies had reported significant differences in thoracic kyphosis between groups, it would not have been possible to establish whether the thoracic hyperkyphosis preceded the shoulder symptoms or if the thoracic hyperkyphosis was a postural adaptation to shoulder pain,” Barrett et al. added.

“The scope of these designs can only provide evidence on the immediate effects of changing thoracic kyphosis on shoulder symptoms and/or provide information regarding the prevalence of thoracic hyperkyphosis in groups with and without pain.”

Research Behind Upper Back Curvature and Shoulder Pain

Like most scientific pursuit, this is not the end of it all when it comes to determining the association between hunching and shoulder pain. The plot may change as quickly as The Walking Dead. Barrett et al. pointed out that the limitation of this systematic review include a “relatively low number of included studies and methodological weaknesses.”

They suggested clinicians to consider that SAPS patients symptoms or any chronic shoulder pain are likely a nociceptive input, based on the central pain mechanism. (2, 3) “Using the history and clinical examination to gauge the degree to which central pain mechanisms are involved in shoulder, may also allow for a more patient specific approach to the assessment and rehabilitation of shoulder pain.” (1)

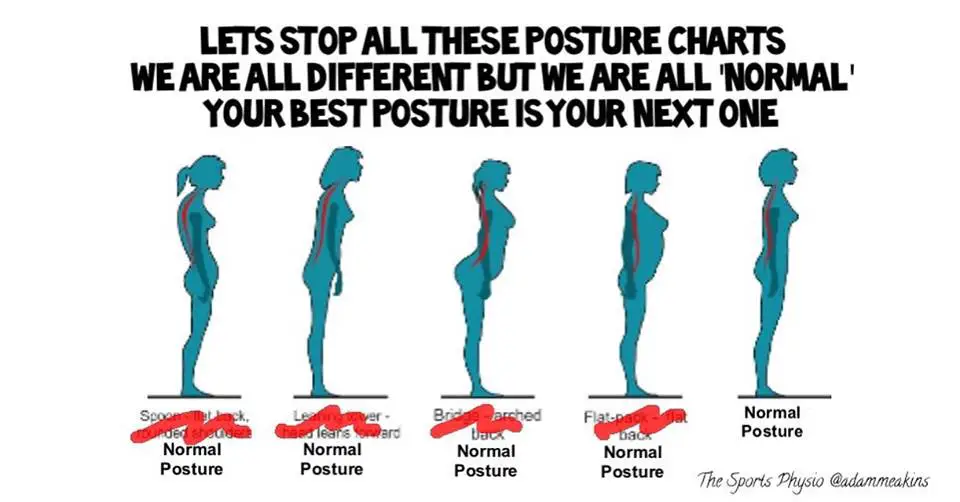

Keep in mind that association is not causation. Sometimes kyphosis may have an association with upper back pain or shoulder pain for a certain population, but it is not necessarily the blame as the evidence suggests. Like neck pain and low back pain, shoulder pain is very likely to be multifaceted, stemming from a mix of pathology, cognition, beliefs, emotions, experience, and physiology. (4, 5)

Although upper back curvature and hunching may not be a risk factor to shoulder pain, reaching for that bag of dog food on the top shelf that your pet loves may be more difficult than someone with less kyphosis. In terms of pain, almost any posture that is held for too long is very likely to get uncomfortable and painful. Thus, the key is timing and variation of the posture.

“If I sprain my ankle running, it might hurt with other activities. Doesn’t mean that these activities caused the pain or are dangerous.” ~ Dr. Derek Griffin

References

1. Barrett E, O’Keeffe M, O’Sullivan K, Lewis J, McCreesh K. Is thoracic spine posture associated with shoulder pain, range of motion and function? A systematic review. Man Ther. 2016 Jul 21;26:38-46. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2016.07.008.

2. Ingraham P. Central Sensitization in Chronic Pain. PainScience.com.

3. Woolf C. Central sensitization: Implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain. 2011 Mar; 152(3 Suppl): S2–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.09.030.

4. Melzack R, Katz J. Pain. WIREs Cogn Sci. 4: 1–15. doi:10.1002/wcs.1201

5. Jacobs D. Melzack’s and Katz’ new paper; Pain. Part 1. HumanAntiGravitySuit.

Further Reading

1. Ratcliffe E, Pickering S, McLean S, Lewis J. Is there a relationship between subacromial impingement syndrome and scapular orientation? A systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2013 Oct 30.

2. Ingraham P. Does Posture Correction Matter? PainScience.com.

3. Hargrove T. Seven Things You Should Know About Pain Science. Better Movement.

A native of San Diego for nearly 40 years, Nick Ng is an editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine, an online publication for manual therapists and the public who want to explore the science behind touch, pain, and exercise, and how to apply that in their hands-on practice or daily lives.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a B.A. in Graphic Communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014.

When he is not writing or reading, you would likely find him weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, or exploring new areas to walk and eat around Southern California.