Cluneal nerve entrapment, also known as cluneal neuritis, cluneal nerve compression, or clunealgia, is where cluneal nerves get “stuck” or irritated at the passage through the fascia near the iliac crest of the pelvis.

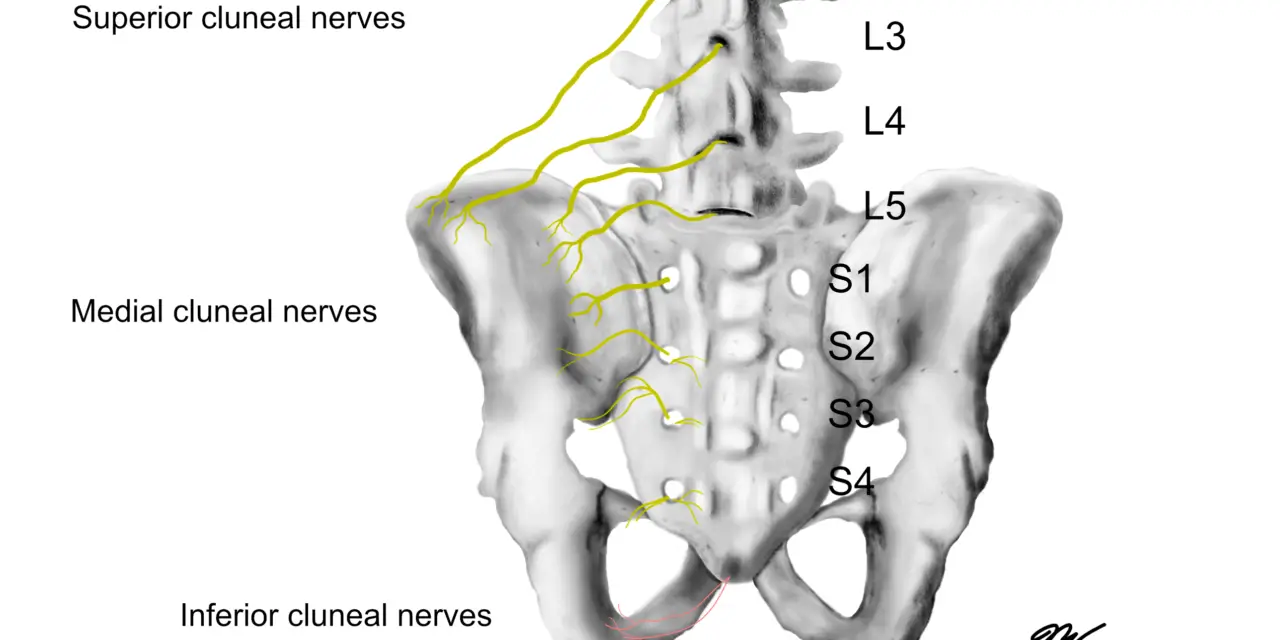

There are three types of cluneal nerves: superior, middle, and inferior. The superior and middle nerves are the ones that tend to get entrapped. This may cause constant friction of the nerves, which may cause deep, achy pain in the buttocks and the lower back.

Symptoms include:

- tingling, numbness, and weakness in the hip and leg

- tenderness in the lower back toward the iliac crest of the pelvis

- tenderness in the buttocks toward the tailbone along the PSIS (posterior superior iliac spine)

- tingling, numbness, and weakness in the hip and pain down the leg

Oftentimes, a physician or physical therapist can diagnose cluneal nerve entrapment by using physical examinations, health history, and imaging tests and is often treated with a combination of physical therapy, medications, and nerve blocks.

Does cluneal nerve entrapment really cause back pain?

Cluneal nerve entrapment may cause low back pain, but there’s no strong scientific evidence that shows a strong causal relationship. As of 2022, there has been no published systematic reviews or similar studies that examines the association between chronic low back pain with clunealgia.

In fact, a team of Canadian researchers scanned the medical literature in 2020 and found 28 articles relating to the etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of cluneal nerve issues. Most of these are single case reports, which only give scant clues to the root of the problem.

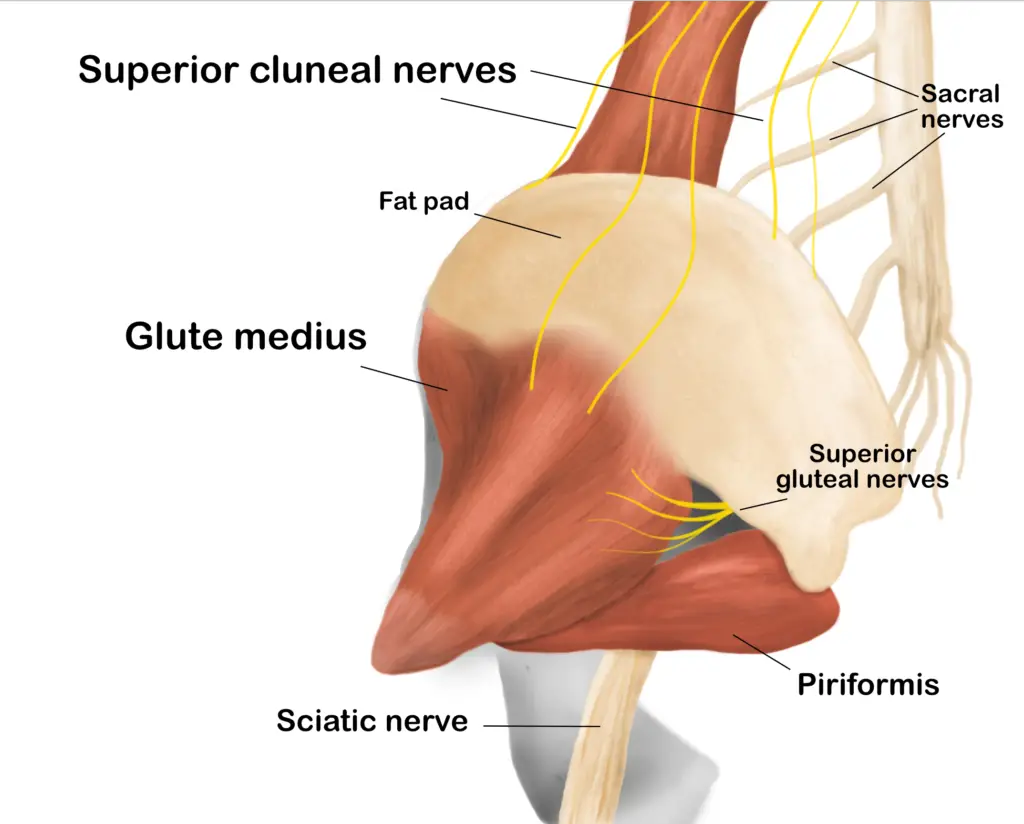

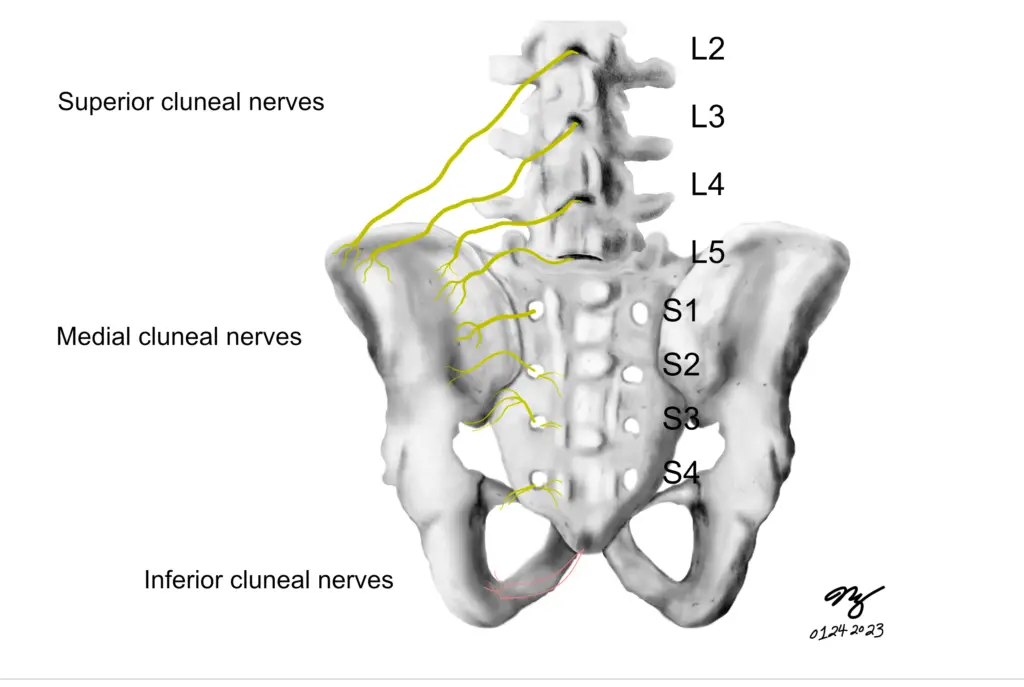

The superior cluneal nerves tends to get entrapped at the passage where they go over the iliac crest and into the glute medius. (Illustration by Nick Ng.)

To make any sense of whether cluneal nerves need to be targeted or not, we would have to look at the body of existing research and basic anatomy, physiology, and pain science to decide.

Pain is “unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage,” according to the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP). It also includes the accepted idea that pain is a personal experience that’s influenced by emotional, biological, psychological, and environmental factors, not just sensory alone.

Like other types of pain, cluneal nerve entrapment alone may not likely contribute to low back, hip, and leg pain, but its nature may likely be highly biologically influenced.

For example, constant rubbing and pinching on a cluneal nerve may lead to inflammatory pain where various biological agents, like cytokines and immune cells, increase your pain sensitivity. This may be caused by lifestyle and environmental factors, such as sitting too long (environmental) and/or stress at work (psychological/emotional).

Current researchers and clinicians disagree on the primary causes of cluneal nerve entrapment. Dr. Yoichi Aota, who is a physician and researcher at the Yokohama Brain & Spine Center in Yokohama, Japan, was involved in several cluneal nerve studies since the mid-2000s. He said in an online interview in 2017 that he has only seen patients with cluneal nerve pain and doesn’t know if anyone has such entrapment with no pain.

But in his case, his patients’ pain experiences aren’t black and white. “Typical patients with mild entrapment have repetitive acute pain occurring several times per year,” he said. “Pain usually is aggravated by movement. This would disturb exercise, such as playing golf. Some patients with chronic and severe entrapment have very severe leg pain lasting all day long radiating to the legs.”

“I started this study [in 2005]. At that time, literature in this topic is very limited. No information was available in the textbook of orthopaedics and spine surgeries.” ~ Dr. Yoichi Aota, 2017. (Photo courtesy of Dr. Yoichi Aota.)

“It is not known if cluneal nerve entrapment could be asymptomatic but probably not. As with any nerve, they do not like to be irritated and react accordingly,” Tubbs said.

Where is the cluneal nerve?

There are three types of cluneal nerves: superior, medial, and inferior.

The superior cluneal nerves stem from nerve bundles (dorsi rami) of the L1 to L3 of the lumbar spine, burrow through the psoas major and paraspinal muscles, and innervate the upper buttocks and the skin above it.

Most of the cluneal nerve entrapment stem from the superior cluneal nerves (SCN), which pass between the iliac crest and the lumbar region of the gluteal fascia that attaches to the crest.

The middle cluneal nerves stem from the dorsi rami of the sacral joint (S1 to S3) and pass through a ligament around the sacroiliac joint (long posterior sacroiliac ligament), which leads toward the middle of the glutes. Sometimes pain in these nerves could be mistaken for SI joint pain.

The inferior cluneal nerves branch from the posterior femoral cutaneous nerve and crawl up the lower buttocks to innervate the skin of that area and the perineum.

Among the three major types of cluneal nerves, the superior cluneal nerves are more likely to get “entrapped” than the others. (Illustration by Nick Ng)

Medial cluneal nerves (MCN) are less likely to cause pain because of their shorter length as they course through multiple layers of fascia. Most physicians would diagnose clunealgia by palpation along the iliac crest or the long posterior sacroiliac ligament (LPSL) where the patient responds to tenderness or pain relief after a local anesthetic injection.

But keep in mind that it’s possible that some people may have different nerve positions due to biological variability. This has been shown in several case studies of the sciatic nerve, the median nerve, and the mylohyoid nerve in cadavers.

What causes cluneal nerves to get “stuck?”

No one really knows why cluneal nerves get stuck, especially the superior cluneal nerves. Aota thinks that several biological factors can increase the chance of getting cluneal nerve entrapment.

“Because humans are bipedal and keep certain postures, such as flexion, posture increases loads in back and buttock muscles and long posterior sacroiliac ligament, which may make SCNs and MCNs to be at great risk of causing pain by irritating these areas,” he said. “Although young patients, like teenagers, sometimes have SCN pain, a majority of SCN and MCN patients are older than 50. That is why I believe that aging is one of the contributing factors.”

Aota added that spinal instability at the part of the spine where the thoracic and lumbar column meet may initiate clunealgia because the SCN starts in this area. Also, someone who has spinal kyphosis after a vertebral fracture may often aggravate clunealgia because the nerve is stretched too far.

Tubbs said that bone grafting from the iliac crest is likely to contribute to cluneal nerve injury and pain. but surgeries near these areas could do the same.

“As the cluneals all have an origin from the spinal nerves or their branches, spine operations could result in their injury,” Tubbs said.

How common is cluneal nerve pain?

Based on a 2014 Japanese study that Aota and his colleagues conducted, cluneal nerve entrapment makes up about 12% of reported chronic low back pain among 834 patients, and half of this population reported leg pain as well. One small Japanese study of 13 patients reported 14%, but such a tiny sample does not represent the larger population.

However, Tubbs and his colleagues stated in their 2010 research that such entrapment is uncommon yet possible, and they didn’t find any such “tunnels or obvious compression sites” that could cause these nerves to get “stuck” among 20 cadavers. They suggested that more obvious and common causes of low back pain and leg pain should be ruled out before considering entrapped cluneal nerves to be a possibility.

“We found no anatomical variation between sex, age, or side,” they wrote.

However, Aota cited a few studies that yielded some evidence that such a cluneal nerve within or under the ligament “is a potential cause for [low back pain] and peripartum pelvic pain” because the nerve bundles pass through or beneath the LPSL.

“SCN tender point was on the posterior iliac crest approximately 70 mm from the midline and 45 mm from the PSIS,” Aota described. “The MCN tender point was on the LPSL within 40 mm caudal to the PSIS.”

However, such palpation methods aren’t very reliable because of the tiny distances that the nerves travel and anatomical variations among different people. Aota said that very few doctors and surgeons know much about clunealgia or even cluneal nerve anatomy.

“I started this study [in 2005]. At that time, literature in this topic is very limited. No information was available in the textbook of orthopaedics and spine surgeries,” Aota said.

He mentioned that French surgeon Jean-Yves Maigne, who is one of early researchers in cluneal nerve’s contribution to back pain in the late 1980s, had reported that SCN entrapment is a rare cause of low back pain. Contrarily, Aota finds that half of his patients have back and leg pain because of entrapped cluneal nerves.

Cluneal nerve entrapment treatments

There are three common treatments for cluneal nerve entrapment: surgery, nerve block, and exercise. For some patients, they may need two or three of these methods to get long-term pain relief, but results aren’t always consistent for everyone.

Surgery

Surgery for cluneal nerve entrapment aims to release the trapped nerve, alleviating pain and discomfort. The specific surgical approach may vary depending on the individual case and the underlying cause of nerve entrapment. Surgeons may use techniques, such as neurolysis (removing scar tissue or other obstructions), decompression (relieving pressure on the nerve), or neurectomy (removing part of the nerve).

During surgery, the surgeon identifies the location of the trapped nerve and carefully frees it from any surrounding structures causing compression or irritation. The success rate of such surgery is promising, but it still lacks enough data to confirm because cluneal nerve entrapment cases are rare—1.6% to 14% in existing studies.

Aota and his colleagues collected data from a 834-patient cohort from 2009 to 2013. These patients had severe chronic low back pain and/or leg pain. Only 113 of them were diagnosed with SCN pain. When less invasive treatments failed to reduce sufficient pain, surgery was performed on 19 patients to decompress the SCN and remove the SCN block.

The surgery had some success. Among 16 patients with leg pain, three had complete pain relief, two had almost complete relief, and three had no improvement. The eight remaining patients had some pain relief within the six months of follow-up, but five of them had temporary relapse of pain post-surgery.

While not everyone had sufficient pain relief with surgery, Aota noted that more than three days of pain relief after blocks had better pain outcomes than those with less than three days.

Nerve block

Nerve blocks, such as lidocaine, are often used to numb the pain. A 2022 prospective study of 25 patients with low back pain on one side of their hip for more than six months had “significant pain relief” for the next six months. However, the study lacked a control group so no one knows if they would have gotten better on their own or with another treatment.

The researchers evaluated the patients’ pain by using a number score and a psychological assessment before they had the injection. After the first shot, they had several injections in two weeks, one month, three months, and six months.

More recently, some surgeons have been using a peripheral nerve stimulation device that is implanted at the painful site, similar to a spinal cord stimulation among CRPS patients.

Dr. Gaurav Chauhan from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Presbyterian in Pennsylvania led a case study of a 65-year-old male patient with low back pain for three years.

After the peripheral nerve stimulator was implanted over his left iliac crest, the patient followed up in six months and reported “more than 80% improvement in pain and more than 80% improvement in function.” He was able to “sit along with his friends without obvious discomfort.”

Exercise

While there’s no evidence that specific pelvic or low back can alleviate cluneal nerve pain or entrapment, exercise in general may reduce pain sensitivity.

A 2022 systematic review of 11 studies show that aerobic exercise (e.g. step aerobics, walking, cycling) could reduce chronic musculoskeletal pain, but the researchers do not know if such pain reduction also improves disability and quality of life.

However, strength training alone has also been shown to be just as good as aerobics for alleviating chronic low back pain (which may be good news to those who don’t like to do aerobics).

Does it matter which type of exercise? The current evidence says no. What matters more is the exercise routine is consistent and enjoyable. Research may be needed to see if the existing exercise for chronic pain research could be applied to cluneal nerve pain.

Because there aren’t many cases of cluneal nerve entrapment and pain, performing higher quality trials can be challenging for researchers. Not only do they have to find willing participants, the symptoms can mimic those of sciatica and many contributors of low back pain, which can be laborious and time-consuming with plenty of elbow room for error.

“Most professional anatomy courses do not teach about the cluneal nerves. Even many medical curricula leave these out,” Tubbs said. “Therapists should be at least aware of these nerves as they will undoubtedly have patients with pain in their distribution and will probably be manually stimulating these branches during some of their treatments. This is not clear as the cluneal pain might be interpreted precisely or lumped together as ‘back pain’.”

A native of San Diego for nearly 40 years, Nick Ng is an editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine, an online publication for manual therapists and the public who want to explore the science behind touch, pain, and exercise, and how to apply that in their hands-on practice or daily lives.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a B.A. in Graphic Communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014.

When he is not writing or reading, you would likely find him weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, or exploring new areas to walk and eat around Southern California.