In early 1985, Jill R. Lawson of Silver Springs, Maryland, gave birth to Jeffrey Lawson, who was prematurely born at 26 weeks. After her son underwent heart surgery to fix a blood vessel near his under-developed heart, Jeffrey passed away five weeks after the surgery at Children’s Hospital National Medical Center.

While his death was devastating to Jill and her husband James, what shocked the Lawsons more was that Jeffrey received only pancuronium, a powerful drug that paralyzes all of his voluntary muscles to prevent movement, which did nothing to alleviate pain.

The Lawsons had no interest in suing the surgeons or the hospital like some parents would. Instead, they advocated for change in how pain is treated for infants. She wrote in an editorial in the medical journal Birth:

“My son, Jeffrey, was a very tiny, very sick premature baby, born Feb. 9, 1985, at a gestational age of 25-26 weeks. During the almost two months of his life, he was on a respirator, with several lung diseases, a heart problem, kidney problems, and a brain bleed. He sometimes became unstable and difficult to manage clinically. In the United States each year, thousands of preemies with identical medical profiles are born and kept alive, and many of them have the same surgery.

“Jeffrey had holes cut on both sides of his neck, another hole cut in his right chest, an incision from his breastbone around to his backbone, his ribs pried apart, and an extra artery near his heart tied off. This was topped off with another hole cut in his left side for a chest tube. The operation lasted 12 hours. Jeffrey was awake through it all.

“The anesthesiologist paralyzed him with Pavulon, a curare drug that left him unable to move, but totally conscious. When I questioned the anesthesiologist later about her use of Pavulon, she said Jeffrey was too sick to tolerate powerful anesthetics. Anyway, she said, it had never been demonstrated to her that premature babies feel pain. She seemed sincerely puzzled as to why I was concerned. It turns out that such care, or lack thereof, is possible because, as a neonatologist explained, babies, unlike adults, don’t go into shock no matter how much agony they suffer. Anesthesiologists take advantage of this, coupled with the patient’s inability to complain.”

A year later, The Washington Post publicized this case to the world, which led to immediate changes by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Society of Anesthesiologists.

It’s quite unimaginable today that doctors and nurses wouldn’t give infants pain medication before a surgery or other conditions. But the history of pediatric pain research and management is quite recent in modern medicine that began in postwar Europe.

Early research includes huge studies on migraines, such as one among Swedish children in Uppsala by Dr. Bo Vahlquist in the mid-1950s and another by Dr. Bo V.S. Bille in the early 1960s—with a follow-up of that population in the mid-1990s.

Another early study from Bristol, England, also paved a path to recurrent abdominal pain among children, which started a snowball effect that questioned how surgery and pain management was done.

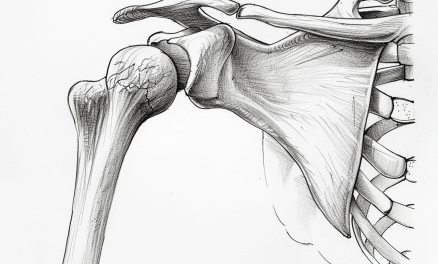

Premature babies didn’t often get anesthesia before surgery or pain care because most doctors thought that their nerves weren’t fully developed to have a pain experience like older children and adults. (Photo by Happi Raphael, distributed under a Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0) license.)

Dr. Patrick McGrath from the Department of Psychology at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, cited one of the first influential studies from 1977 by two nurses from an “obscure nursing book” called “Pain: a source book for nurses and other health care professionals.”

One of these studies by Dr. Jo M. Eland and Dr. J.E. Anderson found that only 12 out of the 21 hospitalized children were given oral analgesics after 21 orders were given out.

When 18 of these kids were matched with an adult sample, the result was quite extreme: All the adults were given 372 opioid and nearly 300 non-opioid pain medications.

“Although the study used a small sample, questionable matching, and did not even measure pain, the extreme differences in pain management between child and adult patients were stunning,” McGrath wrote. “Eland and Anderson noted that only 33 scientific articles, most on pediatric recurrent abdominal pain, had been published up to that time.”

In the early 1980s, two better-designed studies found similar but less extreme results.

McGrath cited one study by a nurse named J.E. Beyer found that 6 out of 50 children who were going to have cardiac surgery were not given any analgesics, but the matching 50 adults going for similar surgeries were all given analgesics.

They also found that those children who received the medications were given less than half of the dosage that were given to adults. This study also did not examine the patients’ pain.

Since the Lawson case, a few of these early studies caught the attention of nursing and academic communities, which eventually leaked into the public and the media.

One British study by K.J.S. Anand, Bloom, and Aynsley-Green that was published in The Lancet in 1987 got notorious media attention. In the study, they compared the stress responses of post-surgical newborns who were given full anesthesia versus those who were given the “Liverpool” technique, which was the “standard” way to give a minimum dosage of anesthesia in the U.K.

On July 8, 1987, an article in The Daily Mail attacked both Anand the study’s supervisor Dr. Al Aynsley-Green because the study deprived infants from pain relief during surgery. Eventually, the public realized that many babies were not given painkillers, despite that there were safe and effective ways to deliver analgesics for newborns.

In September 1987, the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Society of Anesthesiologists, and several pediatric organizations agreed that “the decision to withhold such medication should be based on the same medical criteria used for older patients” and not “based solely on the infant’s age or perceived degree of cortical maturity.”

Since then, the number of pediatric pain research went from zero in 1977—and as high as 9 in 1983—to 28 in 1987. By 1998, that number shot up to 62, with most of the research coming from the U.S., followed by Canada, the U.K., and Sweden.

It’s interesting to see what a few individuals and the media can do to make historical changes in modern healthcare, influencing the direction of scientific endeavors.

Since the late 1980s, tens of millions of children and infants have been given anesthesia for surgeries to avoid unnecessary suffering, thanks to advocacy from many parents like Jill Lawson and the journalists who exposed the questionable practices in pediatric pain care.

A native of San Diego for nearly 40 years, Nick Ng is an editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine, an online publication for manual therapists and the public who want to explore the science behind touch, pain, and exercise, and how to apply that in their hands-on practice or daily lives.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a B.A. in Graphic Communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014.

When he is not writing or reading, you would likely find him weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, or exploring new areas to walk and eat around Southern California.