A lateral meniscus tear is a rip in the cartilage on the outer side of the knee joint, which may cause pain, swelling, and limited knee movement. The incidence of meniscus tears has been reported to be 12% to 14%. This number may be as high as 50% as we age.

Meniscus tears are the second most common injury to the knee. Surgery is often used to treat such tears, but recent recommendations suggest surgery should be delayed in the absence of mechanical symptoms.

Recovery from a partial lateral meniscus tear can be between 16 to 24 weeks, according to a 2022 study. But the researchers reported that there’s no definitive recovery time because there are different variables, such as the type of surgery, treatment plan, exercise progression, and the patient’s age, gender, activity level, and other health characteristics. “…two athletes with the same pathology cannot be expected to follow identical paths towards full recovery,” they concluded.

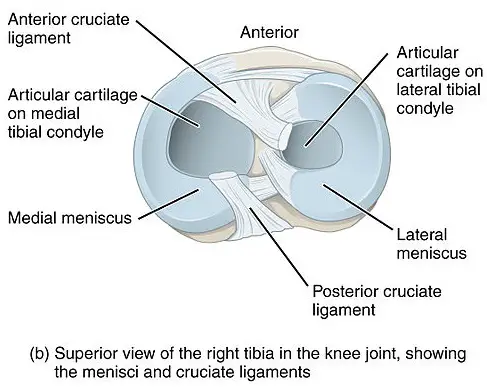

Lateral knee meniscus anatomy

Because the articular surfaces of the femur and tibia do not fit like a ball-and-socket joint of the shoulder, the knee relies on soft tissue structures for stability, such as menisci and ligaments.

The menisci are fibrocartilaginous, crescent-moon structures that attach to the tibia and femur and help improve load distribution and maintain joint stability. The “O” shape of the lateral meniscus covers a more articular surface than the smaller “C” shaped medial meniscus.

Image: BruceBlaus

The lateral meniscus is the workhorse of the two, shouldering 70% of the load through the knee. When working together, the medial and lateral menisci work together to transmit as much as 85% of the load when in 90 degrees of knee flexion.

The lateral meniscus can be divided into three zones:

- Red: outer portion of the tissue and named for its good blood supply

- Red-white: middle third of the meniscus and has fewer blood supply

- White: innermost portion with no blood supply.

These zones are critical in determining the likelihood of a tear healing without surgical intervention. Areas with more blood supply have a higher likelihood of healing areas with fewer blood supply.

When the knee extends, both menisci move forward. While the knee flexes, the menisci are drawn backward. This is both a common injury mechanism and a surgical precaution after meniscus repair as the posterior horns of the menisci may become pinched between the femur and the tibia with deep flexion angles.

Causes

Lateral meniscus tear can be caused by internal or external factors. Internal factors include:

- Anatomical variations

- Discoid lateral meniscus

- Pivoting and torsion

Valgus and varus stresses

Valgus stress is associated with the risk of lateral meniscus damage while varus stress seems to lead to medial meniscus injury and degeneration. An increased Q-angle, which also causes valgus position at the knee, can put excessive pressure on the lateral compartment and may lead to lateral meniscus tears.

Discoid lateral meniscus

A discoid lateral meniscus is an anatomical condition that is unique to the lateral meniscus and may require surgery correction. A discoid meniscus is the most common anatomical variant and is described as thickened meniscus tissue that covers more of the tibial plateau than the normal meniscus. A discoid meniscus can be symptomatic or asymptomatic.

Pivoting and torsion

Another common cause of injury is a quick change from knee flexion to full extension where the meniscus gets pulled back into the space between the femur and tibia. This occurs during the mid-stance phase of running or when returning to the upright position or coming up during a deep squat. In the non-athletic population, this motion can occur when transitioning from stooping to standing or even when stepping off a curb.

In sports and dance, when your foot is planted while changing directions, this pivoting or torsion causes a rotary force that leads to a lateral meniscus injury. Professions that require repetitive deep squatting and kneeling can also increase the risk, such as plumbers, cable technicians, carpenters, and auto mechanics.

External factors of lateral meniscus tears mostly are caused by direct contact to the knee, especially in contact sports. A meniscus tear can happen if you’re hit by an opponent from the side with your foot planted, such as a football tackle.

Lateral meniscus tear symptoms

Symptoms of a lateral meniscus tear include:

- Sharp, local pain at the lateral knee

- Clicking or “popping” of the knee

- Knee effusion (too much fluid around the knee)

- Limitations in knee flexion and extension

- Knee locking if there is a flap tear

Symptoms often start with a popping or tearing sensation in the knee. Pain and swelling then develop over the next few days as inflammation sets in

Related: ACL Tear

Diagnosis

The most consistent clinical finding for lateral meniscus tears is tenderness at the lateral joint line in acute and degenerative tears. It can even be painful or tender when the leg is moved passively by a clinician. In a 2007 study of 130 patients with medial or lateral meniscus tears, the researchers have examined the reliability of the McMurray’s test and joint line tenderness.

All participants underwent arthroscopic surgery where the diagnosis was either confirmed or rejected; 88% of medial meniscus tears and 92% of lateral meniscus tears were correctly identified using those clinical tests alone. Thus, these tests are reliable for diagnosing a meniscus tear.

Sometimes clinicians need to rule out damage to other knee structures.

Acute anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears are often associated with lateral meniscus tears while chronic ACL injuries can drive medial meniscus tears.

Severe injury to the medial collateral ligament (MCL) is likely to involve the medial meniscus because two structures are firmly attached to one another. Conversely, isolated injury to the lateral collateral ligament (LCL) is possible as the lateral meniscus is separated from the ligament by a fat pad.

In the posterior knee, a hamstring strain, Baker’s cyst, or posterior cruciate ligament injury (PCL) may be the source of pain rather than a lateral meniscus tear.

A hamstrings strain will cause pain and soreness at the side and back of the knee, but this pain will likely change with activity (pain improves with rest, worsens with activity) whereas meniscus pain is consistent regardless of the amount or intensity of activity.

Meniscus tears are often associated with Baker’s (popliteal) cysts. It is believed that these cysts are formed by one-way valves that are the body’s way of regulating the hydraulic pressure in the knee when there’s an effusion as the size of the cyst is directly related to the effusion size. A Baker’s cyst isn’t likely to be mistaken for a torn meniscus but finding one could indicate a meniscus tear or another lesion is present.

Similar to a popliteal cyst, deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is unlikely to be mistaken for a meniscus tear, but it can be mistaken for the result of such an injury. If you’re unable to fully extend your knee, you will adopt a plantarflexed ankle position and a toe-touch gait that can create unusual calf pain. If this is accompanied by redness, heat, or cramping, DVT should be ruled out before treatment commences.

It’s possible, but unlikely, that a torn meniscus could cause anterior knee pain. If jumper’s knee and patellofemoral pain syndrome have been ruled out but anterior knee pain persists, a meniscus tear may be suspected.

Do you need surgery?

Currently there’s no consensus as to when or if arthroscopic surgery is indicated. Historically, orthopedic surgeons were quick to perform partial meniscectomies on symptomatic patients, but in the 2010s, the fast-track meniscus surgery has fallen out of favor and been replaced by a meniscus sparing or preservation approach.

A host of randomized control trials have reported no difference in outcomes between patients who undergo arthroscopic surgery and those who don’t at a one-year follow-up—especially in cases of degenerative meniscus tears.

Partial meniscectomy should be reserved for patients who fail conservative treatment (physical therapy, medication, injection) or those with significant mechanical symptoms, such as knee locking that changes gait or causes instability). When possible, a meniscal repair is performed to preserve the tissue. Meniscal repairs also tend to have good clinical outcomes.

Research has shown that patients who had partial meniscectomies report excellent results immediately following the procedure. More than 80% of patients report their knees are normal or near-normal after meniscus surgery however when the lateral meniscus is involved, these positive results aren’t as long lasting.

Repeat lateral meniscus surgery is indicated 14% of the time due to continued impact on activity. Prognostic factors for good outcomes following surgery include which meniscus is involved, the size of the tear, amount of tissue resected, age, and cartilage health. Regardless of which meniscus is involved, osteoarthritis is common after arthroscopic intervention which is one of the reasons meniscus preservation has gained traction.

A 2020 systematic review found that meniscus tears are often identified during reconstruction of the ACL. This is particularly true in cases where surgery is delayed six months or more or there are several incidences of instability. When the meniscus is addressed at the same time as the ACL repair, the likelihood of developing osteoarthritis is increased.

Keep in mind that even a fake meniscus surgery “works” as well as a real surgery. In a 2013 Finnish study, the researchers conducted a double-blind, randomized, sham-controlled study in 146 patients who had medial meniscus tears without knee osteoarthritis. The participants were randomly assigned to either the arthroscopic partial meniscectomy group or the sham surgery group.

Following surgery, the sham group reported higher function and lower symptom scores than the real surgery group. In fairness, both groups had significant improvement at the end of the study, but the patients in the surgical group had “no significant benefit over sham surgery.”

In a 2019 narrative review, the researchers noted that randomized control trials support the idea that both surgical and non-surgical treatments are better than nothing, but no study has been able to determine that surgery is superior to conservative management in degenerative meniscus tears.

In degenerative tears, the British Journal of Medicine is strongly against the use of arthroscopy in most patients.

Treatments

Conservative management may be the preferred treatment option for lateral meniscus tears. However, patients with severely limited range of motion, clicking, popping, locking, or instability are not good candidates for non-surgical treatments. Initial management of an acute meniscus tear should include controlling pain and swelling and restoring range of motion.

Such treatments include:

- RICE (rest, ice, compression, elevation): Mitigate pain and swelling

- Gentle, pain-free range motion exercises

- Walking assistive devices: Using crutches, a brace, or a cane allows walking with minimal gait deviations and offload the injured area. Offloading brace can be used with meniscus tears to normalize gait, decrease pain, or both.

- Physical therapy: Initial phase is to decrease pain and increase range of motion. The next phase should focus on improving leg strength, particularly the quadriceps, hamstrings, and gluteal muscles. The final phase should be plyometrics, dynamic proprioceptive training, and sport-specific exercise as indicated.

Orthobiologics

Orthobiologics—or stem-cell treatments—are substances used to enhance or assist your body’s own ability to repair and regenerate musculoskeletal tissue. Evidence for the use of platelet-rich plasma injections after meniscal tears is scarce but promising. The multiple anabolic growth factors found in platelet-rich plasma may play a role in healing meniscal lesions, particularly in the white-zone that lacks a blood supply.

Platelet-rich plasma is also strongly supported in scientific literature as a treatment for knee osteoarthritis, which is often a co-diagnosis in patients with meniscus tears. This treatment inhibits the inflammatory effects of osteoarthritis in the cartilage.

Mesenchymal stem cells are a group of stem cells that have been extracted from bone marrow, periosteum, trabecular bone, adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, and teeth. These cells can participate in several cellular processes including homeostasis of tissues, remodeling, and repair.

Adipose-derived stem cells are another subset that has been isolated for their role in restorative processes. These cells are easier to isolate and are more abundant in the body than mesenchymal stem cells. Although research is limited, both have shown encouraging results in the treatment of knee pain and meniscus tears.

Despite showing good results, orthobiologics are not currently covered by Medicare or other insurers so physical therapy remains the road most traveled as the out-of-pocket costs for platelet-rich plasma and stem cell treatments can be prohibitive. Without a direct comparison of the treatment options, it’s impossible to know if one is better than another, but the good news is that they all seem to help.

As with any medical condition, consult with a physician or qualified medical professional to determine the best course of treatment for their condition. This article should not be considered a substitute for professional advice or care.

Massage for lateral meniscus tears

While the lateral meniscus cannot be targeted by massage therapy, the surrounding muscles and tissues can. Massage therapy recommendations for lateral meniscus tears follow the physical therapy evidence in that they rely on knee osteoarthritis findings.

Meniscus tears are often associated with an abnormal walking pattern, which may lead to tight hamstrings, gastrocnemius, or soleus. Therefore, massage for lateral or medial menisci tears should also focus on these areas.

Hamstring tightness is often addressed with classic massage techniques, such as Swedish massage. Researcher Diana Hopper and her colleagues compared classic massage to dynamic massage and found that those who received dynamic massage gained more flexibility than those in the other group. Moderate pressure massage has proven useful in lateral hip pain as well.

Field et al. investigated the effects of weekly 20-minute massages and found decreased pain and stiffness as well as improved function, mood, and sleep. These subjects continued to benefit from the effects of massage at one-month follow-up.

Massage therapy is a widely accepted treatment for patients with knee osteoarthritis. A 2017 systematic review of seven randomized controlled trials on the use of massage therapy in 352 patients with knee osteoarthritis found that massage improved their walking function. The review also found that increasing quantities of massage led to more reduction in pain and improved self-reported function.

In a 2016 review by Field et al., the data suggest massage therapy on the quadriceps and hamstrings is an effective way to improve knee range of motion and improve range of motion-related pain. Notably, this review also endorses self-massage on the days between sessions to enhance the overall effects of massage.

(Photo: Penny Goldberg)

Self-massage using a foam roller or roller massager has been found to have wide-ranging effects. Monteiro et al. had 18 active men perform foam rolling or roller massage to their anterior thigh. Range of motion tests done before and after the treatment showed improved flexibility immediately and 30 minutes later. These quick benefits make self-massage ideal before a workout or during the warm-up phase of physical therapy.

Further reading

Why Does Bending Your Knee Hurts and What You Can Do

Massage for Joint Pain: A Biopsychosocial Approach

How Massage Therapy Can Treat Chronic Pain

Penny Goldberg, DPT, ATC

Penny Goldberg, DPT, ATC earned her doctorate in Physical Therapy from the University of Saint Augustine and completed a credentialed sports residency at the University of Florida. She is a Board Certified Clinical Specialist in Sports Physical Therapy.

Penny holds a B.S. in Kinesiology and a M.A. in Physical Education from San Diego State University. She has served as an Athletic Trainer at USD, CSUN, and Butler University.

She has presented on Kinesiophobia and differential diagnosis in complicated cases. Penny has published on returning to sports after ACL reconstruction and fear of movement and re-injury.

Outside of the clinic, Penny enjoys traveling, good cooking with great wine, concerts, working out and playing with her dogs.