Massage therapy is well-known to reduce body aches and promote relaxation, and its benefits may extend further for those with osteoarthritis.

While massage therapy shows promise in pain reduction, its effectiveness can vary depending on the severity of the condition and individual factors, such as lifestyle, genetics, prior experience with massage, and stress.

Understanding its potential—and limitations—can help those with osteoarthritis make informed decisions about incorporating massage into their treatment plan.

What is osteoarthritis?

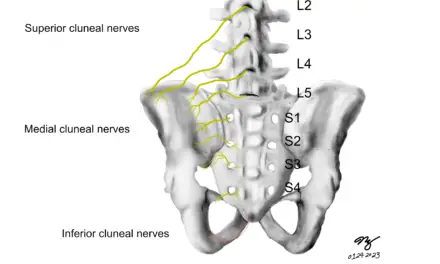

Osteoarthritis is the progressive degradation of the articular cartilage, the smooth tissues covering the ends of bones in joints and within intervertebral discs. This cartilage provides a low-friction surface for joint movement while bearing significant loads. Despite the longevity of collagen within the cartilage, its healing capacity is limited, even for minor injuries.

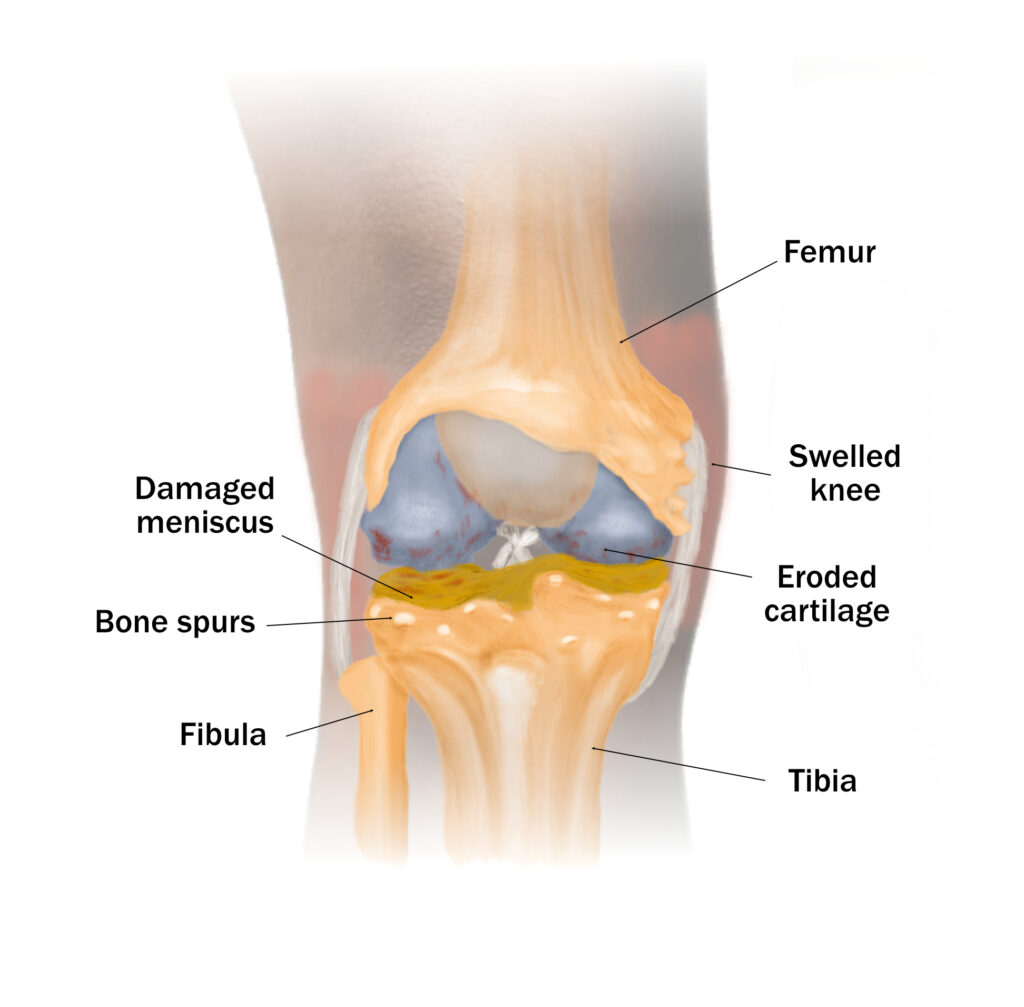

Common symptoms of osteoarthritis include damaged meniscus, eroded cartilage, and bone spurs. (Illustration by Nick Ng)

While cartilage degradation is the most visible aspect, osteoarthritis affects the entire joint structure, including the synovium, ligaments, and subchondral bone—the bone layer beneath the cartilage.

Inflammation plays a crucial role in osteoarthritis development and progression. One hypothesis proposes that degraded cartilage triggers a foreign body response in synovial cells, leading to the production of metalloproteases (type of enzymes that breaks down protein), new blood vessel formation in the synovium, and inflammatory cytokines, which further worsens cartilage destruction. Alternative theories emphasize the role of activated synovial macrophages and the innate immune system in osteoarthritis progression.

Osteoarthritis is not just “wear and tear”

Osteoarthritis was thought to be a disease of “wear and tear,” caused by chronic overuse and poor joint mechanics wearing down the cartilage. This leads to symptoms such as inflammation, stiffness, swelling, and reduced mobility. However, several research have challenged this idea.

A 2010 systematic review revealed an association between weight, body mass index (BMI), and the development of hand osteoarthritis—despite hand joints not being weight-bearing. This suggests that factors beyond joint mechanics are at work, pointing to systemic effects related to obesity, such as those linked to metabolic syndrome and atherosclerosis, which may influence osteoarthritis throughout the body.

Interestingly, a 2017 study of mammals with osteoarthritis found that dolphins and dugongs (a relative of manatees) can also develop osteoarthritis even though they spend their lives in the ocean. In the samples, signs of osteoarthritis were found in the dolphins’ left and right humeral trochlea and the dugongs’ lumbar vertebrae.

And so, osteoarthritis is far more complex than just biomechanical issues; it also involves inflammatory and metabolic factors.

One such potential mechanism involves adipokines, such as leptin. These signaling molecules are produced by fat tissues, which can drive inflammation and change metabolism across the body, potentially playing a significant role in joint health and the progression of osteoarthritis.

Thus, osteoarthritis should no longer be conceived as a simple “wear and tear” condition. Instead, it should be considered a complex physiological condition that involves biomechanics, hormones, the immune system, and genetics.

Massage precautions for osteoarthritis

There are some situations where massage therapy may not be safe or recommended.

These include:

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT): Massage may dislodge a blood clot, particularly in the legs near major veins.

Acute infections: Massage may spread certain infections, such as influenza A, in the body if it is done too deeply to cause rhabdomyolysis.

Open wounds or cuts: These areas should be avoided during a massage.

Broken bones: Areas with fractures should not be massaged.

Skin conditions: Some skin problems might make massage uncomfortable or unsafe, such as impetigo and fungal infections.

Recent injury: Massage should be avoided for at least 48 hours after an injury or as recommended by your physician or physical therapist.

Tumors: Direct pressure over active tumor sites should be avoided.

What’s the best type of massage for osteoarthritis?

While there are few studies about massage therapy for osteoarthritis, basic pain science can help explain how massage can reduce pain.

Based on the gate control theory of pain, massage reduces pain by stimulating large nerve fibers that compete with nociceptive signals, effectively closing the “pain gate” in the spinal cord. This process blocks these signals from reaching the brain, which changes pain perception. Also, massage creates non-painful sensations, such as touch and pressure, which travel quickly to the brain and activate inhibitory interneurons and keep the gate closed.

Therefore, most types of massage that involve lighter pressure would work in pain relief, such as Swedish massage and lomi lomi. Massage therapists should adjust the pressure according to each patients’ preference and avoid deep pressure.

Also, Swedish massage was found to reduce pain among people with knee osteoarthritis in a 2017 study. The massage group’s outcome was better than the groups that received light touching or “usual care.” However, the benefits of massage lessened after eight weeks. By week 52, there was “no significant difference” among all groups. For more details, see the story of how the massage study on knee osteoarthritis was done.

Does exercise reduce osteoarthritis symptoms?

In addition to medications, diet modifications, and supplements that your physician and/or dietitian may recommend for osteoarthritis, exercise can help delay the progression of the disease and reduce its symptoms.

A 2023 systematic review of 31 randomized-controlled trials—with a sum of more than 4,300 people—found that therapeutic exercise for hip or knee osteoarthritis had a small, positive effect on reducing pain and improving physical function compared to the non-exercise group.

However, this improvement might not be very meaningful in the long run, the researcher wrote.

People who started with worse pain and physical limitations saw more exercise benefits than those with less pain and better function. This suggests that focusing on exercise programs for those with more severe osteoarthritis symptoms could be more helpful.

However, the researchers also wrote that their findings questioned the extent of the expected benefits of exercise, “adding to a growing body of evidence that raises uncertainty about the role of exercise in osteoarthritis.”

They gave an example of a 2022 randomized-controlled trial that suggests improvements associated with exercise may largely result from placebo effects, contextual influences, the natural progression of the disease, or regression to the mean—rather than the direct effects of exercise itself.

Furthermore, a group of Scandinavian and Dutch researchers wrote in 2024 that the current evidence “is not sufficient to support claims about (lack of) causality” between exercise and knee osteoarthritis pain because the evidence does not fulfill the minimum requirements of the Bradford Hill criteria of evidence. The Bradford Hill criteria is a set of nine guidelines used in epidemiology to determine whether a relationship between two factors is likely to be causal or not, such as a treatment and a disease. These criteria include factors like strength of association, consistency, and biological plausibility.

The researchers wrote that most of the studies have not been designed specifically for assessment of dose-response relationships in exercise for knee osteoarthritis. “Such studies are challenging as there is no consensus on what dose (of which modality) of exercise that is necessary for inducing therapeutic effect,” they wrote.

Resistance or aerobic exercise for osteoarthritis?

Research finds both aerobic and resistance exercises can reduce pain and other symptoms of osteoarthritis. A 2021 systematic review of 19 trials found that doing strength training, aerobics, and Pilates eight to 12 weeks, three to five times a week for one hour “appear to be effective” in reducing knee pain and improving strength. Aquatic and land-based exercises also have “comparable” effects.

This means no type of exercise is “better” than another in reducing osteoarthritic pain. In fact, exercise itself can reduce pain.

Nick Ng is the editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine and the managing editor for My Neighborhood News Network.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a bachelor’s in graphic communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014. In 2021, he earned an associate degree in journalism at Palomar College.

When he gets a chance, he enjoys weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, and exploring new areas in the Puget Sound area in Washington state.