We massage therapists have a lot to offer to people in distress from pain, depression, anxiety, and other conditions, and the numbers show that we are desperately needed. So why aren’t we already working as healthcare providers?

The need is certainly there. American physician David Eisenberg’s 1993 article on patterns of usage in the U.S. showed that patients are willing to pay out of pocket for massage and other treatments considered “alternative,” and the interest and attention in the quarter of a century since then has only reinforced that point. Then what is the barrier?

Our education is a huge part of what is keeping us away from a place at the healthcare table. A total training time of 500 to 600 hours at the vocational/technical level of education—even if it concentrated on all the right areas—does not compare with a doctorate in medicine, nursing practice, physical therapy, or a master’s in social work or occupational therapy.

In Washington state, where massage therapists are legally defined as healthcare providers, this distinction among the haves and have-nots is also enshrined in law: we have all the responsibilities of healthcare providers, such as mandated reporting and not committing malpractice, but we are not eligible for state reimbursement and referral since those privileges are specifically reserved for master’s-level and higher education. That hierarchy is not going to change any time soon, if it ever does.

For the sake of argument, in the previous paragraph, I assumed “even if massage therapy education concentrated on all the right areas,” which it certainly doesn’t. (Of course, there are individual good schools that teach massage therapy on the basis of reality. But when the client’s access to valid information about healthcare is randomly and totally based on the luck of which school an massage therapist happened to go to, then that is not the basis of a universal profession.) So even in those states that require more than 600 hours, if the extra time is devoted to topics that won’t prepare them for healthcare environments, then that extra time is not of much value.

Raising the Bar in Massage Therapy as a Healthcare Profession

Students regularly write to me complaining that, in massage school, they’re subjected to anti-vaccination and anti-fluoridation screeds in class time; to implausible theories about the world that were debunked centuries ago outside of the alternative-medicine bubble; to teachers reciting strings of science-y world salad together that make it painfully obvious that they have no idea at all what they are talking about; to New-Age victim-blaming via “The Secret.” All of these were taught instead of valid knowledge within the scope of practice of massage therapy that a healthcare provider needs to practice successfully in a 21st-century interdisciplinary clinical environment.

The lack of accountability in initial massage education, and the willingness of our U.S. massage professional to sign off on just about any nonsense as being relevant somehow to massage continuing education, is what ensures that massage therapy will not be systemically taken seriously as a real healthcare profession any time in the near future. The community college programs in massage therapy—although they don’t address the master’s/non-master’s healthcare provider gap—at least are accountable to real accreditation agencies and have to provide a valid curriculum. In this way, they provide the foundation for a real healthcare provider education as the basis of massage therapy. This is a very welcome development, although it still remains a tiny minority of massage programs.

But a great deal of room for improvement in the foundational curriculum remains, especially as the future becomes more interdisciplinary. In order to build a body of knowledge about the natural world, health, illness, how massage works in reality, and how to function successfully as a healthcare provider in modern clinical environments, I propose a basis for a massage therapy curriculum that truly and visibly prepares graduates for working in healthcare as real and accountable professionals.

In “Threads and Yarns: Weaving the Tapestry of Comorbidity,” published in Annals of Family Medicine in 2006, American physician Barbara Starfield created a powerful medical practice metaphor that can resonate with and inspire many of us:

“As any weaver knows, the elegance of a fabric lies in the yarns, not the threads. The whole is lots more than the sum of its parts. In health services, the threads are the diagnoses on which interventions are based. (1) How these threads are spun into yarn (the underlying biodynamic of the tapestry of health) is poorly understood. Part of the problem is the imperative to “sell” diagnoses in order to market the interventions associated with them. Those who make their living by focusing on diseases resist understanding that health is a pattern.

“Without grasping the pattern, management is at best an approximation of adequate care.”

What to Take Away

1. Diagnoses are important, but in themselves, they are not the most important focus of health services [epidemiology, health services, systems thinking]. There is a larger pattern to health that is more than the sum of its parts, and we don’t yet understand it very well [science, systems thinking].

2. Understanding it better is the key to delivering optimal health services, but there are incentives in the system to keep people focused more narrowly on diagnoses in isolation instead [humanism, systems thinking].

3. Because so many people are living with multiple and complex conditions, and adverse effects occur in the interactions among these conditions and their various treatments, we need to switch from a disease focus to a focus on the interactions among various components of health in individuals and in populations [humanism, science, systems thinking, population thinking].

4. If we want to be healthcare professionals, then we have to be aware of and engage with health services because it is the vehicle through which healthcare interventions—including massage—are delivered to the patients who need those interventions [health services].

Dr. Starfield also drew upon multiple areas of shared healthcare professional knowledge, which should be consistent with epidemiology, health services, humanism, population thinking, science, and systems thinking. Even though each of these is an entire specialty in itself, they contain core concepts and threshold concepts that should be represented in our curriculum because they are shared knowledge among healthcare professionals. (2)

She and the many healthcare professionals who share her values worldwide are our natural allies in working not only to develop massage into a real healthcare profession, but also to ensure that it is grounded in the kind of healthcare system that we truly want to be a part of. In this article, we will use her tapestry metaphor as a foundation to describe a proposal for a curriculum to give us the knowledge we need to fully participate in that system.

“Most of her research addressed health services research or the science of how to deliver good, fair and affordable health care to a total population in a country. She had a strong focus on key elements in a well functioning health care system such as a person and not a disease approach to patients, and a holistic and not a single disease approach to the meeting between the patient and the doctor in the consultation room. She fought passionately for more equity in health, and to her sudden death she was traveling around the world to promote primary care as a tool to create better health care and better health.”

She was professionally active writing, traveling, and speaking at conferences on health equity and social determinants of care right up until her unexpected death at age 78. This photograph of her was taken in Montevideo, Uruguay, in November 2010, seven months before she died.

Identifying the curriculum warp and weft: What do we want for massage as a healthcare profession?

Are we professionally where we want to be yet? I don’t think we are, and I don’t see many massage therapists online expressing satisfaction at where we are as a group. But I also don’t see a lot of effective action happening to make the situation better either.

One reason for this situation, I believe, is that we in the U.S. have—deliberately or accidentally—created an epistemic bubble for massage. Inside that bubble, narratives tend to be more important and more highly-valued than facts, and anything goes. Steve Kirin, the CEO of the National Certification Board for Therapeutic Massage and Bodywork (NCBTMB), has stated unequivocally regarding approval and certification of continuing education classes that, “We are here to do a detailed review but we have no right to say that something is or is not ‘real’ in the holistic profession.” (3)

As a direct result of this refusal to commit to reality and realism in massage therapy as it’s practiced in the U.S., and to protect our clients against misinformation (deliberate or unknowing), outside the epistemic bubble we’ve created, this is how we’re perceived in the public.

Massage Therapy Identity

Wikipedia classifies “massage” with other forms of “alternative medicine” as “pseudo-medicine.” That outside-of-the-bubble perception that massage is “pseudo-medicine” is a huge problem for our efforts to get traction as mainstream healthcare professionals.

But is it a fair one?

You may be wondering if massage is really widely regarded as pseudo-medicine, why are you hearing more and more about more hospitals and other mainstream facilities accepting massage? It is true that more and more facilities are tolerating our volunteering efforts for free, or are letting patients pay for us out of pocket. But when it comes to respecting and valuing us enough to pay us a professional salary out of their own resources, and to invite us to have a place at the professional healthcare team’s decision-making table, I’m not seeing much positive changes along those lines. I connect this lack of progress right back to the widespread perception of massage as pseudo-medicine.

What we need is a massive effort to break that bubble and to build a real, fully-fledged, mainstream healthcare profession outside of it that is valued on its own terms, and that can be depended upon to provide a reasonably good living to its members.

The first step is to identify what makes up a healthcare profession in reality, and to decide whether it’s what we want to commit to. Then we can use that commitment to develop a new curriculum to get us on that path.

Values of Patient-Centered Healthcare Professions.

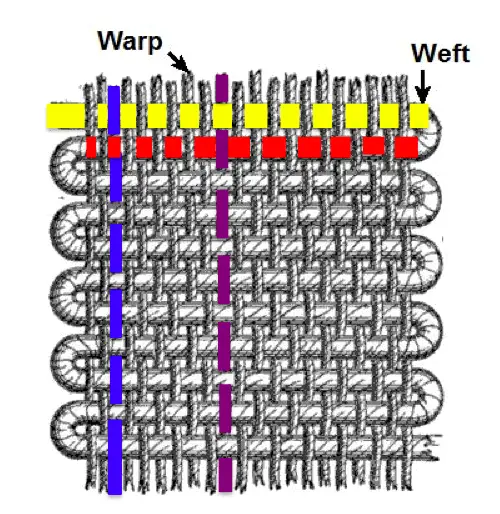

In the following illustration, the blue warp yarn represents healthcare professional ethics, and the purple one represents self-care. The yellow weft thread represents professional exploration, and the red one represents service outreach.

Illustration: Ravensara Travillian

The part where the blue warp crosses the yellow weft—the intersection of healthcare professional ethics and professional exploration–might represent remaining securely within massage ethical scope of practice while crafting a new role within affective massage therapy for the client’s behavioral-healthcare team. Purple (self-care) might intersect yellow (professional exploration) by participating in a “Clinicians Get Creative” workshop, to ensure that we get our own needs for self-expression in our personal lives met, without putting those expectations on our clients in our professional lives.

In another example, blue (healthcare professional ethics) might intersect red (service outreach) in implementing the principle of equal access to healthcare by developing a sustainable way to reliably deliver massage to a particular underserved population. Purple (self-care) might intersect red (service outreach) by teaching a class on mindfulness for massage therapists, or by teaching clients simple stretches they can do on their own at home.

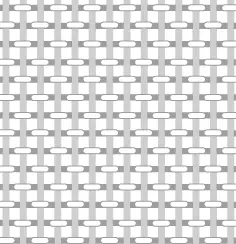

Weaving together means interlacing the threads of the warp and the weft. In the simplest weave, called a plain weave or tabby weave, each weft thread crosses over one warp thread, under the next warp thread, over the next warp thread, and so forth.

The next weft thread follows a similar pattern, but that pattern is offset by one thread—where the previous weft thread, as well as the next one crosses over, this one crosses under, and where the previous and next weft threads cross under, this one crosses over.

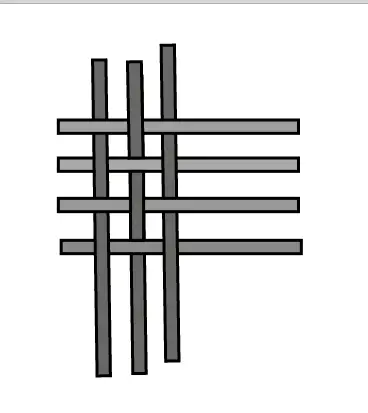

Each place that the warp and weft cross each other, whether the crossing is over or under, represents an intersection, as seen in the left illustration.

For example, when the weft thread symbolizing “Structure of a massage session” intersects “Medical science” and “Health equity”, it represents an opportunity for teaching therapists how they should ethically and professionally handle intake interviews in the face of media hype about health scares.

For example, during the 2014-2016 West Africa Ebola virus outbreak, we saw many massage therapists online declaring that they were going to take the temperatures of any clients who had traveled to Africa, and refuse to treat anyone they judged to have a “fever”—or, even worse, just refuse to treat anyone who had traveled to “Africa”, no matter what part. Discussing interactions among scope of practice, non-discrimination, geography, and microbiology in the context of what is appropriate in an intake interview for massage therapy could have prepared therapists to deal with the situation, and prevented a lot of the fear-based flailing around for solutions that we witnessed. Also, it could have prevented a lot of the damage done to massage therapists’ public and professional image.

Image: Jeancourt, Wiki Commons

These metaphorical intersections of warp and weft each represent a teaching opportunity for how therapists can intersect and engage with healthcare professionalism. Thus, they represent a bridge our clients and to the members of the healthcare professional team.

The Bigger Picture of the Massage Therapy Education

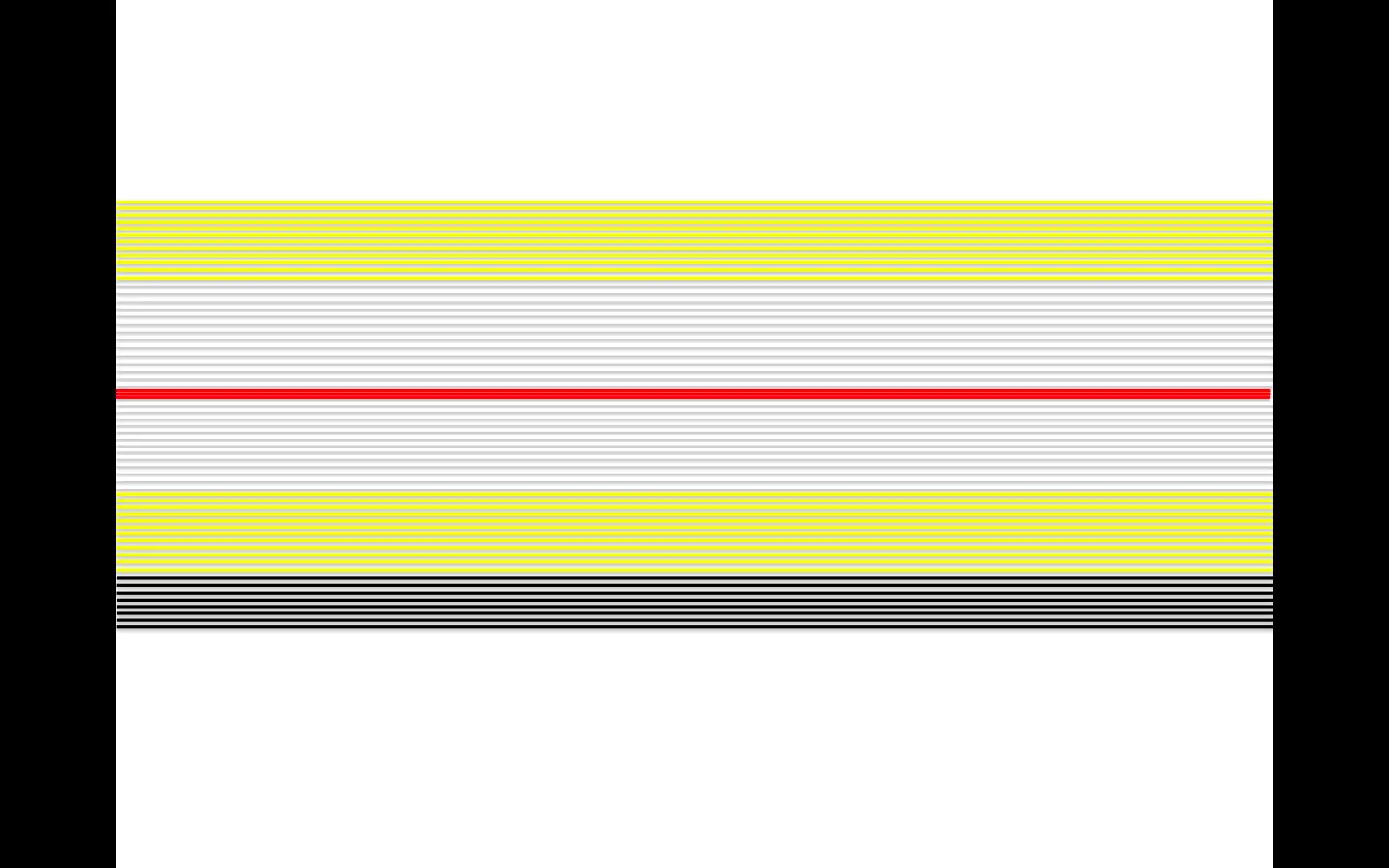

In our metaphoric weaving our future, we have four areas of the proposed curriculum be our weft, marked with different colors.

Illustration: Ravensara Travillian

We can visualize the warp in this way, marked by three areas and colors.

Overlaying the weft onto the warp, we get an idea of how the whole will look like when it’s woven together:

Overlaying the weft onto the warp, we get an idea of how the whole will look like when they are woven together:

Illustration: Ravensara Travillian

A sample of what would entail a new massage healthcare professional curriculum include the elements of shared professional healthcare knowledge that we’ve encountered in this article:

Massage therapy

Theoretical basis;

Plausibility, credibility, and trustworthiness;

Massage clinical practice (including supervised clinical experience with vulnerable and underserved populations that we have not traditionally worked with);

Interprofessional experiences and teamwork

Core and threshold concepts in STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts and humanities, Mathematics) (5,6)

Consensus science;

Frontier science;

Pseudoscience/Anti-science/Quackery;

Biology, Chemistry, Physics, Psychology;

Decision-making and problem-solving in healthcare contexts;

Social sciences/Social determinants of health;

Epidemiology (7), Immunology

Technology

Social media and healthcare professionalism;

Quality and safety;

Engineering;

Processes in the natural world

Arts and humanities

Philosophy/Critical thinking/Reasoning/Logic;

Ethics/Health equity/Humanism;

Research integrity;

Patient centeredness, quality and safety;

Scope of practice, roles, and boundaries;

Realism/Materialism/Naturalism

Cultural awareness, cultural responsiveness and community

Mathematics

Population thinking and probabilities;

Exploration and career focus

Dedication to advocacy in health equity, public health, and global health;

Entrepreneurship;

Mentoring and finding mentors;

Leadership;

Lifelong learning

Our next steps include:

1. Determine what are appropriate core concepts and threshold concepts in each field for massage therapists to be exposed to and to demonstrate competency in.

2. Determine how much time is appropriate to allocate to students who are already proficient in science, and how much time and what scaffolding structure is called for for students whose background education did not provide that advantage.

3. Figure out how these needed competencies fit into the constraints imposed by varying state licensing laws.

What Benefits Do Our Clients/Patients Want?

We can make a huge difference in the health, well-being, and quality of life of our clients through our students. How we choose to use that influence and power is a question of crucial importance.

The curriculum solution proposed here is to publicly sever our attachment to claims about health, illness, and interventions that are inconsistent with the healthcare professional values that Dr. Starfield identified, and to commit instead to the shared healthcare professional body of knowledge. Note that we also commit to defining and using terms from other disciplines in the way that those other disciplines use them. We explicitly commit to stop appropriating terms such as “toxins,” “energy”, and “fascia” from other disciplines and redefining them in ways that do not match reality about the natural world. The list of topics to include in the curriculum so far, both from first principles and from Starfield’s implicit body of knowledge reads:

A new curriculum based in reality and science is not sufficient to get us to the table, but it is a necessary first step. The future of professional massage is in our hands. For our clients and for ourselves, let’s have the courage to make the changes we need. ♠

With clear goals and a clear sense of a mission in a changing health system, we might yet, in time, create a much better system than we now have.

~ Dr. Barbara Starfield

References and Footnotes

1. Olesen F. In Memoriam, Professor Barbara Starfield. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2011 Sep; 29(3): 130.

4. An Interview with Steve Kirin, New CEO of NCBTMB | LauraAllenMT.com

5. Core concept: A fundamental principle that is integral to understanding a subject. Without understanding the core concept, someone does not understand the subject. For example, the law of conservation of mass and energy is a core concept of understanding how energy works in the natural world, which, in turn, is a core concept of physics.

6. Threshold concept: A core concept that transforms a person’s understanding of a subject by providing a new and radically different insight into how things work. Once a student understands a threshold concept, they gain a much deeper understanding of the subject itself. For example, the theory of evolution is a threshold concept of biology.

7. Epistemic: related to the study of what we know and how we know it.