Many healthcare professionals have teachers who have made an impact in their career and personal lives where their influence continues to thrive even after they pass on. One such teacher was Dr. Loren “Bear” Rex, who was an osteopathic physician and founder of the Ursa Foundation in Edmonds, Wash., a 501(c)(3) nonprofit.

While Bear passed away in October 2019, some manual therapists—including massage therapists, physical therapists, and athletic trainers worldwide—still carry on his legacy in their practice. Tim Geil, who is a licensed massage therapist in Shoreline, Wash., and co-owner of Geil Manual Therapy, said that Bear was “an outstanding clinician, a profound educator, and a deep thinker.”

“He was a social being and loved people. He had friends from many walks of life, from students and patients, to bluegrass musicians, to childhood friends and fellow circus performers,” Geil said. “They all gathered annually at the ‘Pig Barbeque’ at his unique home in Edmonds for conversations with new and old friends, great food, and wonderful bluegrass music.”

Geil was in his fifth year in practicing when he took his first class at the Ursa Foundation, which was “Evaluation and Treatment of the Cervical Spine and Cranial Base.”

“I remember coming back and telling my soon to be wife that I had come across something very profound,” Geil said. “Bear taught how to treat dysfunction with sophistication, precision, and finesse in a way I didn’t realize was possible. Even more importantly, he explained the reason behind treatment. Dysfunction wasn’t just something causing pain, it was a physiological disturbance in the dynamic balance of the body.”

What attracted Geil is the physiology angle that Bear taught, including how embryonic development helped therapists get a better understanding of connective tissues. Bear’s tenants of manual therapy were “listen, think, feel, treat.”

“I was lucky enough to study with Bear for around 15 years before he retired, taking four to seven courses a year,” Geil said.

Tim Geil, LMT, with Bear in 2019. (Photo courtesy of Tim Geil)

The house on Robin Hood Dr. where Bear taught his classes is no longer there. It was torn down in 2015 for new housing. In the 2008, Bear taught at a small strip mall near Main St. and 212th St. SW, which is now a chiropractic office.

“My study with Bear transformed everything I do as a manual therapist, every patient interaction, communication and treatment,” Geil recalled. “One of Bear’s maxims (what he called Bear Droppings) are: Don’t Treat Pain, Treat Dysfunction; Treating Pain Usually Doesn’t Get Rid of Dysfunction; Treating Dysfunction Usually Gets Rid of Pain.

“Bear taught me how musculoskeletal problems are actually whole body problems, affecting many other systems of the body. When I treat and talk to patients, I am constantly communicating and relating how one part affects the whole.”

The building where the Ursa Foundation used to be in Edmonds, Wash. Dec. 29, 2021. (Photo by Nick Ng)

Bear never told anyone why he called himself after the animal, yet no one addressed him as “Dr. Rex,” said Jeanie Blair, who was Bear’s partner of more than 15 years. “Maybe it was because he was very hairy,” she said. He also had a huge collection of bear figurines in his home in Edmonds.

Bear’s teachings and influence initially came from Andrew Taylor Still, who was the founder of osteopathic medicine in 1874. Because of Bear’s love of knowledge, he pretty much got ideas and influences from almost everyone whom he connected with.

“It might be some little out of the way town in the outback in Australia that he would know the history of, or it might be that he could recite all the states in order forward or backward, and he knew every state capital city and all 39 counties in Washington state,” said Blair. “He just thrived on knowledge. I think he really admired Dr. A.T. Still. I know every now and again he would say something like, ‘I think old A.T. would say something like, “Yup, you got that one right, Bear”.’

Bear’s mother, Mildred Alvena Brown, was also another influence, who was a schoolteacher in a one-room schoolhouse in Rich Hill Townsend, Missouri in the early 1920s, “also a big part of who he was.”

“He was the most amazing person I ever met,” Blair said. “He never talked down to students and never put down anyone.”

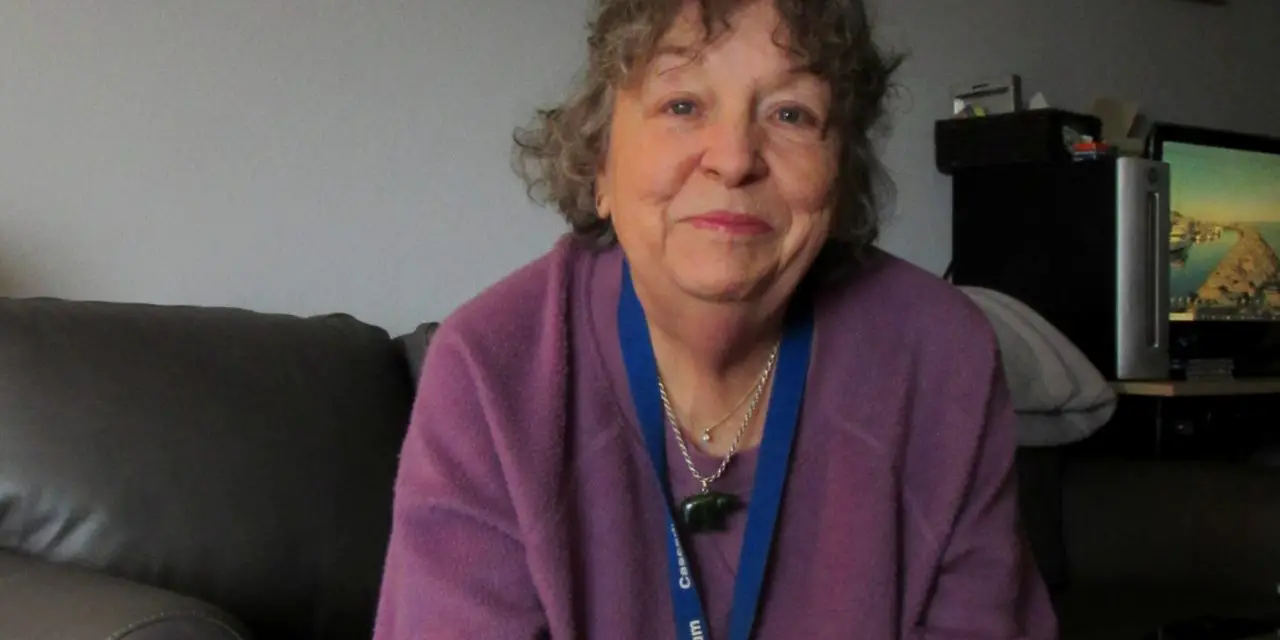

Bear with Jeanie Blair in the early 2000s. (Photo courtesy of Jeanie Blair)

![“I remember [Bear] telling a class if you want to make a name for yourself, just find a parade and get in front of it,” Jeanie Blair said. Feb. 16, 2022. (Photo by Nick Ng)](https://massagefitnessmag.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Jeanie-1-1024x768.jpg)

“I remember [Bear] telling a class if you want to make a name for yourself, just find a parade and get in front of it,” Jeanie Blair said. Feb. 16, 2022. (Photo by Nick Ng)

The Ursa Foundation never expanded to the point like several manual therapy schools did in the 1970s to 1990s, like Upledger and Barnes. Blair said that it was about being “the best,” not the biggest.

Bear started the Foundation in 1976 with two osteopathic physicians, Dr. William Devine and Dr. Dana Devine, who were classmates with Bear during medical school in Kansas City, Mo., after having taught courses together since 1974.

“He was a Renaissance man in many ways. He had very good insight in the application of physiology and applied anatomy to the disease process,” said William. “He and I both had patient populations that we work with their physiology at different levels.”

Although osteopathic physicians in the U.S. work hand-in-hand with medical doctors in most hospitals and clinics, William distinguishes a few major differences between the two professions.

“It’s basically an integration of manual treatment into the treatment of disease,” he said. “We’re pretty much patient-oriented and we actually pick up diagnoses probably easier because of the way we look at patients. It’s much easier to treat the symptoms than just writing a prescription to treat a disease.”

Bear with colleagues and students at the Robin Hood house in Oct. 1, 2016 in memory of Dr. John Chappel, a neonatal physical therapist. (Photo courtesy of Jeanie Blair)

Physiotherapist Diane Jacobs, who is a retired physiotherapist in Weyburn, Saskatchewan and the author of “Dermoneuromodulation,” said that the classes at the Ursa Foundation were able to adapt to her “short” stature when she first took it in 1983.

“I was still in operator mode at that time, and any manual therapy I’d been exposed to previously had been developed by tall people (males usually) with long arms,” Jacobs said. “You pretty much had to be perpendicular over somebody to exert downward forces of various intensities upon various supposedly palpable bony prominences of the spine.”

Jacobs prefers the “contract-relax” techniques that Bear taught, which was similar to what she already learned in physiotherapy school.

“This was perfect!” she said. “I liked the guy, I liked the way he taught, I liked WHAT he taught, I was all in. I moved from Regina to [British Columbia] that same year because I wanted to be a manual practitioner, so I could eventually be my own boss. Physios are not taught that in basic school.”

The Ursa Foundation had its first class in the new location in 2008. (Photo courtesy of Jeanie Blair)

Back in the 1970s and 1980s, Jacobs said that physiotherapists were taught how to help hospital patients move and “shake up” patients to help them cough up their phlegm if they were working in the cardio-pulmonary unit. They had to learn to use tilt tables, crutches and walkers, parallel bars, and wheelchairs while dealing with public relations, nurses, doctors, and other hospital staff.

“He didn’t make stuff up; he tried to stick to principles, but he read all the time and if some studies came out that said you can’t affect skull sutures, he would teach that. He wouldn’t teach disproven stuff, but he would continue to teach the moves because those two things weren’t the same thing.” ~ Diane Jacobs, PT

“And frankly I was bored with all that, sick of some of it, and looked for a way out of it so I could make a living out in the world outside of hospital work,” Jacobs said. “Bear was my ticket out of that context. I made my escape to the west coast and started attending his workshops only 2.5 hours south of Vancouver. It took a while, about seven years more, before I felt sturdy enough to open my own shop.”

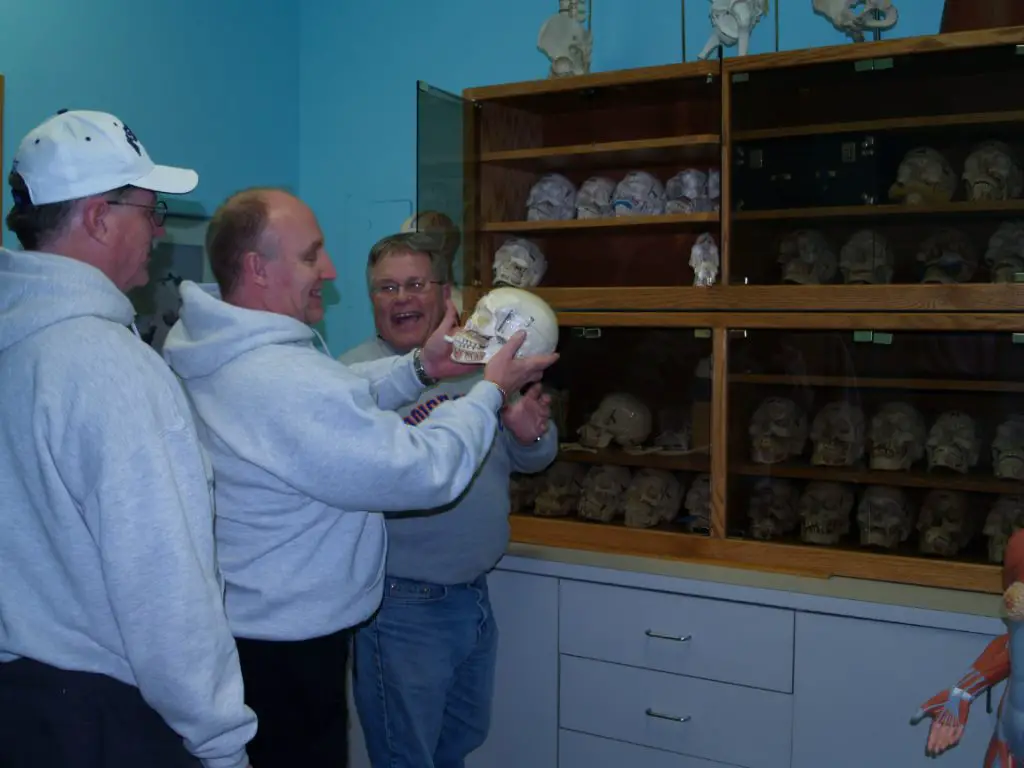

Students at the Ursa Foundation share a laugh at the Edmonds location in 2008. (Photo courtesy of Jeanie Blair)

Jacobs did tons of volunteer work outside of physical therapy as well as “lots and lots” of locums. The latter gave her a peek to see what was going on inside private physical therapy clinics within and outside of Vancouver. Meanwhile, she was still driving to the Ursa Foundation about five to six times a year until 1998 when renowned David Butler, a physiotherapist and pain researcher from the University of South Australia, taught in Vancouver.

“I became enchanted by neurodynamics then, with every bit of relevance realization I felt when I had first encountered Bear and Ursa,” Jacobs said. “He taught more physiology than anatomy, and in retrospect, that was good. He didn’t make stuff up; he tried to stick to principles, but he read all the time and if some studies came out that said you can’t affect skull sutures, he would teach that. He wouldn’t teach disproven stuff, but he would continue to teach the moves because those two things weren’t the same thing.”

Jacobs recalled Bear saying that anyone with a pair of hands could have a manual therapy practice and make a decent living. It didn’t need to be a ton of money but enough to live a stable life.

“He’d say, if you charge $100 for a session, figure out how many per day you would need to do to make an income of $100,000 per year,” Jacobs said. “Working for yourself. Not being paid by some lowball insurer.”

“He just thrived on knowledge. I think he really admired Dr. A.T. Still. I know every now and again he would say something like, ‘I think old A.T. would say something like, “Yup, you got that one right, Bear”,’ Jeanie Blair recalled. Feb. 16, 2022. (Photo by Nick Ng)

The Ursa Foundation also attracted a few registered massage therapists (RMTs) in Canada. Ann Sleeper, RMT, who retired from practicing in early 2020 after practicing for nearly 40 years in Vancouver, B.C., said that she was interested in the Ursa Foundation because the teachings went beyond the Swedish massage technique that she was taught in school.

“[Bear’s] mission was to teach his students, mostly American PTs, to opt out of the restrictive PT system there and to look at their patients as whole people, not just a body part that needed quick treatment,” Sleeper said. “He also allowed any manual practitioner with state or provincial licensure to come to his classes. So there were other massage therapists there sometimes.”

Sleeper first attended the Ursa Foundation in 1991 and continued to travel to Edmonds from Vancouver twice a year until 2003 when her chronic pain condition made it hard for her to commute that far. Even so, her learnings from Bear formed the cornerstones of her own teachings to RMTs.

The Ursa Foundation had its first class in the new location in 2008. (Photo courtesy of Jeanie Blair)

“Bear taught osteopathy in as science-based a way as osteopathy ever gets,” she said. “Bear’s courses were so information dense that many of us taped his lectures. I spent many hours at home transcribing those tapes. His lectures on the anatomy and function of the autonomic nervous system and how much we can affect it in treatment were especially influential. It really helped my patients understand symptoms like mood change, upset stomach, and the other symptoms beyond pain that patients can get, especially after car accidents and falls.

“I consider myself lucky to have discovered the Ursa Foundation, and it was an important link between my original training and more recent pain science concepts.”

There are few physical legacies remain of the Ursa Foundation in the virtual and physical worlds, but Bear’s teachings and relationships he had established continues in his students’ practices and publications. In some ways, it’s similar to how the history of pain science had changed from the times of Ambroise Paré and René Descartes to Ronald Melzack and Tasha Stanton.

“I remember [Bear] telling a class if you want to make a name for yourself, just find a parade and get in front of it,” Blair said. “He was always able to connect to people at all levels. That is a very special skill.”

Bear (l) with colleagues and students at the Robin Hood house in Oct. 1, 2016 in memory of Dr. John Chappel, a neonatal physical therapist. (Photo courtesy of Jeanie Blair)

Bear moved the Ursa Foundation to an smaller office building in Edmonds, Wash., in 2008. (Photo courtesy of Jeanie Blair)

A native of San Diego for nearly 40 years, Nick Ng is an editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine, an online publication for manual therapists and the public who want to explore the science behind touch, pain, and exercise, and how to apply that in their hands-on practice or daily lives.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a B.A. in Graphic Communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014.

When he is not writing or reading, you would likely find him weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, or exploring new areas to walk and eat around Southern California.