Regression to the mean describes the tendency of events or phenomena that go back to an average state after it has run its course in one extreme. Various academic fields have similar definitions of regression to the mean, such as in psychology and philosophy.

Regarding your health, if you have extreme low back pain, then it’s likely that your pain will reduce—or regress—to your “normal,” whatever that may be. It may be mild pain or no pain at all.

If the pain eventually reduces on its own, theoretically, almost any type of intervention—even bogus treatments—may seem to be “effective” or “it works.” This is an important concept in understanding how and why treatments work or not.

First, you’ll often hear regression to the mean in discussions on how to evaluate research. By “evaluating research,” we mean knowing how to tell the difference between good research and flawed research. Distinguishing between them helps us understand what good research tells us about how the natural world works in reality, and how we can use that knowledge for the benefit of our clients.

Healthcare professionals value this good judgment because if you can see past superficial appearances to know what really happened and how you can tell the difference between perception and substance, then you can make valid recommendations for treatment that provide actual value for your clients.

Your clients can, in turn, trust you to tell them the truth, and to carry out your professional responsibility to put their interests ahead of your own with integrity, dignity, and respect. In this way, they can make solid healthcare and treatment decisions grounded in autonomy and informed consent.

Regression to the mean in research

Some researchers identified three categories of non-specific effects—ancillary factors—that interact with treatment and healing, which can cause confusion in design and interpretation of research trying to identify treatment outcomes.

Their third category, “placebo response,” where improvement is observed after an inactive treatment, is perhaps the most well-known. Their first category, the effects of natural history of the disease (many conditions just get better over time, with or without treatment), is also an important one, often overlooked in manual therapy research.

Their second category, the effects of “the regression of the symptoms to their mean intensity,” is what we’ll examine. While reading research, if you understand that it’s a well-known phenomenon in the natural world that:

- Results that look dramatically improved (or worsened) the first time they are measured can look much more ordinary (or average) the next time they are measured;

- Results that look ordinary the first time they’re measured can look dramatically improved (or worsened) the next time they’re measured;

- These changes can happen for reasons that have nothing to do with the intervention being studied (in our case, most of the time, this intervention will be massage treatment).

With the understanding of regression to the mean, you’are less likely to be misled by superficial impressions into wrong interpretations of what the research really means.

You’re more likely to understand the substance and the real meaning of the studies and to provide your clients with better and more valid information for them to decide their healthcare options.

What does regression to the mean mean?

Regression means “going back,” and mean means “average.” This is the phenomenon where measurements that were extraordinarily high or low at first return to more typical values in a later measurement, or where measurements that were average at first are extraordinarily high or low in a later measurement.

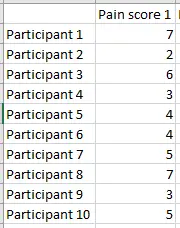

Regression to the mean example

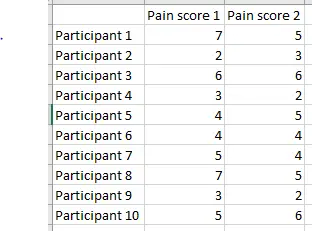

Let’s look at an imaginary, yet plausible, example. Ten participants in a study are asked to report on a scale from 1 to 10 how much pain they are experiencing. Here’s the data for their first report.

Image: Ravensara Travillian

We can calculate the mean (average) pain score for this group, and it turns out to be 4.6. Now we can graph how far away each participant in the study is from the group average.

Image: Ravensara Travillian

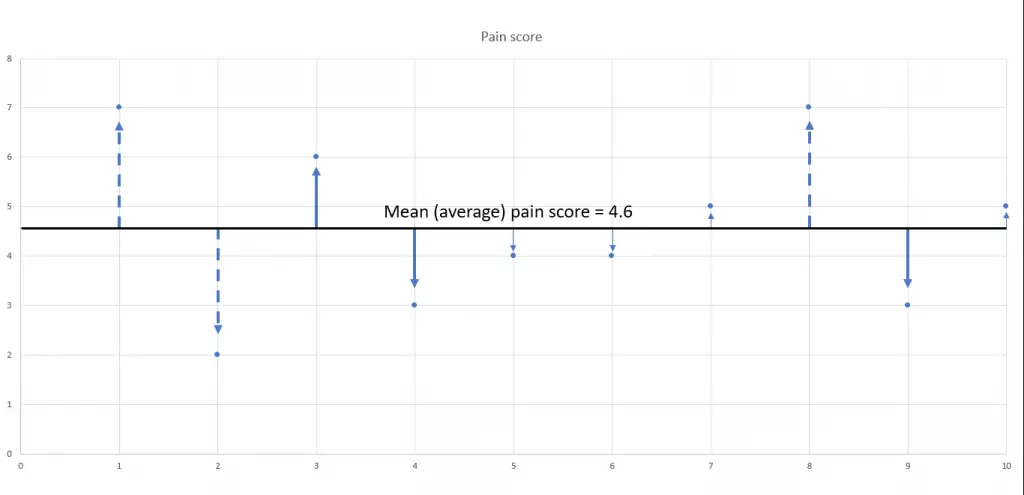

Participants’ pain scores indicated by the thin arrow (5, 6, 7, and 10) are very close to the group mean pain score. Participants’ pain scores indicated by the thick solid arrows (3, 4, and 9) are a little further away from the group mean, and participants’ pain scores, indicated by the dashed arrows (1, 2, and 8), are the farthest away from the mean.

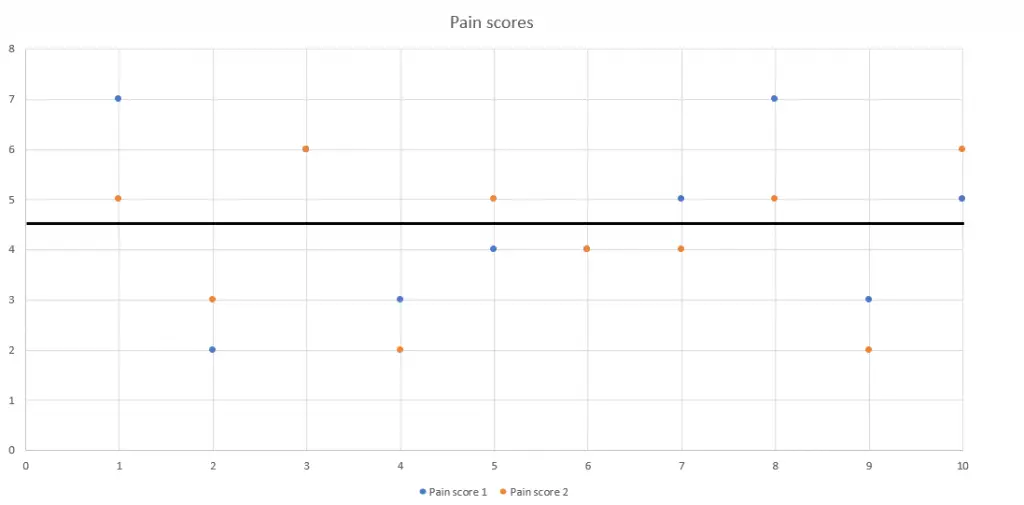

The researchers measure the participants’ pain scores again, and the new results are listed beside the previous results:

Image: Ravensara Travillian

We can graph these pain score values as well (brown points) and compare their distances from the mean with those of the original results (blue points). Remember, the only thing that has changed is that the pain score was measured again—there was no intervention or treatment carried out.

For participants 1, 2, and 8, the brown point is closer to the mean than the blue, meaning that the second measurement demonstrates regression to the mean. They got there in different ways, though—participants 1 and 8 report a decrease in pain while participant 2 reports an increase.

Image: Ravensara Travillian

For participants 4, 9, and 10, the second pain score (brown) is further away from the mean than the original (blue), meaning less pain than before for participants 4 and 9, and more pain for participant 10—again, without any intervention or treatment.

For participants 3, 5, 6, and 7, their second pain scores are almost or exactly as close to the mean as their previous pain scores were.

Participants 3 and 6 reported no change at all, which is why you see only one point for each of them—the brown second point printed right over the original blue point.

Participant 5 reported an increase in pain, and participant 7 reported a decrease in pain, but—in comparison to the group mean pain score—these changes were not extreme. Again, these changes occur without any intervention or treatment.

Although this example of regression to the mean is imaginary and is designed to make it more relevant to the outcomes we and our clients care about, the data is plausible. Real-life examples can be found in every field of human endeavor from baseball to finance and more.

Regression to the mean in massage therapy

Many healthcare professionals in other fields grapple everyday with the problem of trying to distinguish real therapeutic effects from ancillary effects that introduce confusion over what treatments really work and why they work. We can learn from and support each other in our mutual mission of finding out what treatments work best for our clients and patients.

Think about the exercise we just went through with the pain-score data. We saw changes in pain scores (improvement as well as worsening of pain, sometimes dramatically so). That exercise is exactly what we would do if we were looking at a massage therapy study to see if it decreased pain scores, and those changes are exactly the changes we would look for to see if massage therapy helped.

The problem here is that the changes occurred in the total absence of massage therapy or any other intervention or treatment. That’s where the potential for confusion comes in.

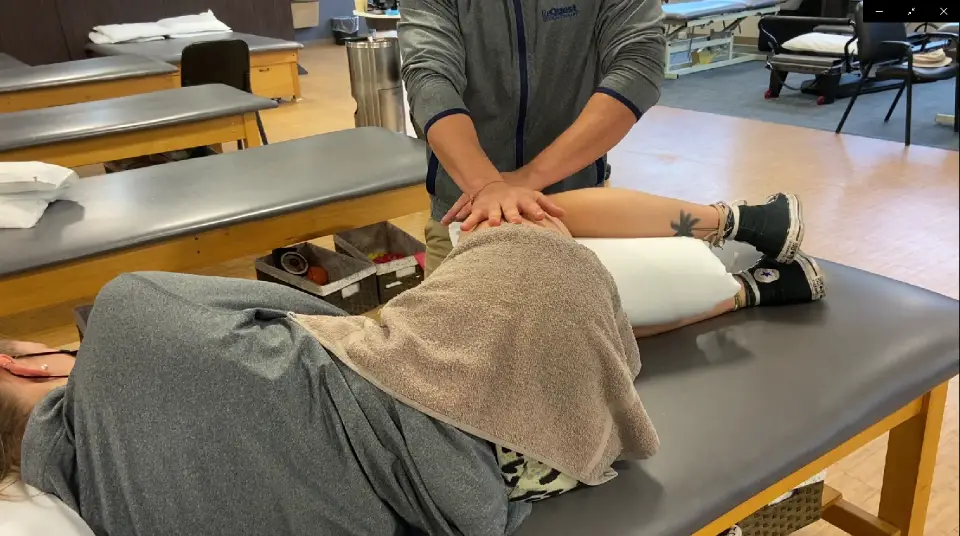

Oftentimes, no one really knows if a massage treatment actually works or not with regression to the mean as a factor in how well a patient responds to a treatment. Photo: Penny Goldberg.

Regression to the mean is an ordinary occurrence. It can, however, look exactly like a treatment effect, and we may not be able to tell the difference between the perception of a treatment effect versus the reality of no treatment effect. If you take the change at face value—a naïve reading of the research—you will think that massage had an effect that it really didn’t have.

If we’re taken in by the perception and get the substance and reality of what actually happened wrong, then we can provide invalid information to clients. In turn, clients—who trust us to get this right—are basing their healthcare decisions on the bad information we give them with the potential of causing suffering and financial harm to them.

This responsibility is why it’s so important for us to develop our discernment and get everything as right as we possibly can. Getting it perfectly right every time is impossible, but the more that we are right, the better we fulfill our healthcare responsibilities to our clients, to our healthcare professional colleagues, to our emerging profession, and to each other.

Study designers should take regression to the mean into account and design accordingly, but the word “should” is doing a lot of work since researchers don’t always do everything they should do. It’s their job to demonstrate to us that they did their work correctly, and it’s our job to be skeptical, to evaluate how well they carried out their work, and to withhold accepting their conclusions and their narratives until they credibly convince us that their work actually did what it’s meant to do.

As part of your evaluation, ask yourself whether the research you’re examining has adequately accounted for the effects of regression to the mean. If they explicitly address the issue, and explain how they’re avoiding confusion from that ancillary effect, and if their explanation is convincing and makes sense, then that’s even better. But most papers won’t address it, and so you have to think about what it would mean.

Think outside the vending machine—how might regression to the mean be operating in this study design, and what would that mean for understanding the results and interpreting them for our clients? A good study design uses multiple points of measurement over a longer time frame rather than just two because the before and after in such a small sample can be an example of nothing more than regression to the mean.

Further reading: How to Fact-Check Massage Therapy Research: 6 Things to Look for.

Pay attention to individual variation, as these effects can get lost in averaging as well. Read the Methods and the Results sections carefully: they’re more important than the abstracts and narratives in the Introduction and Conclusions sections for understanding what’s really happening.

Look for the presence of a control group because without it, you can’t tell what would have happened anyway in the treatment group, with or without the intervention.

Science is an integrated whole—a system—and so, we use systems thinking to evaluate and apply it in real-world-practice. It’s not just random facts in isolation that we have to struggle to keep memorizing.

If we understand aspects of it, those parts are going to reinforce and be consistent with the rest of it. We don’t have to continuously keep starting over from scratch since they are coherent. We can build on and reuse knowledge we’ve already gained.

Part of the knowledge that healthcare professionals share is that research is not a vending machine—you don’t just feed a certain number of tokens in, and wait for the right answer to pop out, fully formed. Instead, you have to use what you know about the natural world to evaluate how good the research is, how trustworthy it is, and how likely it reached the right answer for the question it’s studying.

Reality, life, and biology are all complex, and even under the best of circumstances, they’re not easy to study. Deciding which aspects you should consider and how much weight you should give to each of them to avoid misunderstanding results is neither trivial nor easy. The task is made harder by several factors that are not treatment effects (what we are looking for), but that can look deceptively like those treatment effects.

If you’ve read this far, and grappled with how intense and complicated and frustrating this material can be, then I want to recognize you for your commitment to learning more about how research works, both for the benefit of your clients and for the profession. Thank you for your dedication.

Acknowledgement

Huge thanks to Christopher A. Moyer, PhD, who let me bounce ideas and questions about regression to the mean off him while I was writing this article. Any misunderstanding or error that may have crept in is totally on me, not on him.