There are a lot of special tests in physical therapy that aren’t all that special. When it comes to low back pain and sciatica, the slump test isn’t one of them. This test checks the important boxes. It’s easy to perform (and hard to mess up!), and when it’s positive, there’s no ambiguity.

Pain and symptoms brought on by the slump test have even been known to elicit audible yelps (read: screams) from patients which further helps confirm the positive finding.

What is a slump test in physical therapy?

To perform the slump test, the patient is put into a provocative position to recreate symptoms related to neurological pain. This pain may be caused by a herniated disc, neural tension, or other altered neurodynamics.

The slump test position maximizes the stretch on the nervous system. While the descriptions of the slump test can vary slightly, the positive sign (pain) and what it indicates (neurological involvement) are the same.

According to Dr. Tim Shay, a physical therapist at the UF Health Orthopaedic and Sports Medicine Institute who specializes in spinal pain, the slump test is used as part of a regular exam in patients with low back pain.

He notes that this test isn’t a “stand alone” but part of a constellation of tests and measures. “I’m attempting to find out if it is an acute radiculopathy, chronic radiculopathy, neural tension/nerve entrapment, or hamstring tightness,” he said.

It’s important to talk to the patient about what they feel during this test. Often a patient will report “pain” in the hamstrings that is a result of a tight muscle but can be misconstrued as a positive slump sign.

Symptoms reported in the hamstrings during the slump test should be correlated with patient reported symptoms and other measures of muscle length to determine if this is a true positive or tight hamstrings.

How do you perform a slump test

To perform the slump test:

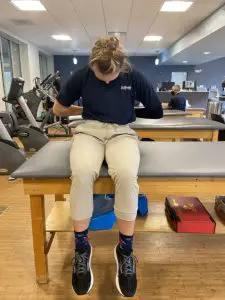

- Have your patient sit on the table/plinth with their hands behind their back and a neutral spine;

- Ask them to slump forward by relaxing their thoracic and lumbar spine (round their back) and note any neurological symptoms (numbness, burning, tingling, shooting, etc.) in the new position;

- Next, ask them to bring their chin to their chest; the examiner provides overpressure into cervical flexion and notes any symptoms that are present;

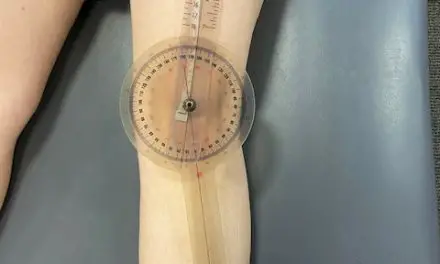

- The patient is then asked to bring their ankle into dorsiflexion and extend their knee. Increased symptoms should be noted. If they are unable to straighten their knee, the available knee extension should be measured;

- The patient should then be asked to extend their neck and any symptoms recorded;

- Finally, they should relax their leg and return to the initial position so that the other side may be tested;

- Repeat all steps on the other side. (Photos by Penny Goldberg)

Differences in knee extension angles can be used to make side-to-side comparisons as well as track progress and recovery.

It’s important to note that neurological symptoms may be elicited at any point during the test. If the patient reports these symptoms, the test does not continue.

Non-neurological pain and symptoms may also be present during testing. You should take notes of these findings, but the test continues throughout the entire sequence of movements unless the neurological symptoms are elicited. Non-neurological pain or symptoms are not indicative of a positive slump test.

What does a positive slump test mean?

A positive slump test tells us that neurological structures are involved. Additional information from the history and clinical exam are necessary to determine if the pain is coming from a disc, neurological tension, or some other altered neurodynamics.

When determining the source of dysfunction, the quality of the pain is an important differentiator, and whenever possible, patients should be asked to describe their pain.

Patients with pain that is of neurological origin tend to use words like shooting, burning, tingling, and/or numb. If the patient reports hamstring pain that is deep, dull, or aching this should point the clinician toward a musculoskeletal pain origin rather than neurological pain.

Pain from the slump test is often unilateral. The radicular pain that is associated with disc herniation and pain from sciatica are often felt on only one side. Bilateral neuropathic pain tends to be related to stenosis (a narrowing of the canal that houses the spinal cord and its elements) rather than disc herniation or neural tension.

What is femoral nerve entrapment and how is the slump test involved?

Not all slump tests are created equal. “A slump isn’t always a slump. In the case of the femoral slump test, there are some shared principles but the structure being tested is entirely different,” Shay said. “The femoral slump test is looking exclusively at the femoral nerve.”

Femoral nerve entrapment can occur at a few places along the course of the nerve. The nerve can be stuck under the iliopsoas (hip flexor) tendon or inguinal ligament, or further down the thigh in the adductor canal. If the femoral nerve is entrapped by the iliopsoas tendon symptoms will reproduce in hip extension, often during the modified Thomas test (typically referred to as the Thomas test).

If the nerve is caught under the inguinal ligament, the patient may experience quadriceps weakness; if it’s trapped in the adductor canal, the patient may have pain in their knee or the inside of their lower leg and foot. Functionally, this condition causes difficulty when walking and may create sensations of knee buckling.

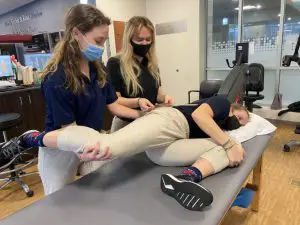

The Femoral slump test is relatively uncommon in clinical practice. This neurodynamic test is performed in a side-lying position with the bottom hip and knee in full flexion and secured by the patient’s hand.

Photo by Penny Goldberg.

The examiner stands behind the patient and supports the involved leg at the knee (in knee flexion). The patient’s leg is brought into hip extension with knee flexion while the patient flexes and extends their neck to elicit symptoms. Pain in the front of the knee is a positive finding in this test.

Lin and colleagues examined the use of this test in patients with anterior knee pain (not otherwise caused by nerve tension). Nearly 30% of those who underwent the femoral slump test with anterior knee pain had a positive test.

This suggests that it might be worth investigating femoral nerve involvement in those with anterior knee pain even in the absence of other neurological symptoms.

Clinically, if you’re trying to rule in disc involvement, rule out hamstring involvement, or anything in between, the slump test is a quick easy way to gather a ton of good data about your patient’s pain and symptoms that can help guide the rest of your exam.

How accurate is the slump test?

The slump test has acceptable sensitivity and specificity. sensitivity.’ These terms refer to the test’s ability to correctly identify those with positive findings while ‘specificity’ is the test’s ability to correctly identify those without positive findings. In diagnostic testing, having a high sensitivity and specificity is ideal.

A 2008 Turkish study examined 75 patients with low back pain. Thirty-eight of them had imaging of the spine that confirmed disc herniation; thirty-seven had unremarkable imaging.

The slump test and straight leg raise were performed on all patients. The results indicated that the slump test was more sensitive (84% vs. 52%) and only slightly less specific (83% vs. 89%) than the straight leg raise.

Recently, researchers sought to improve the diagnostic accuracy of the slump test. A Canadian study from the University of Manitoba included 21 patients with low back pain that may or may not have had radicular pain.

In addition to the standard symptoms with the slump test, these researchers also recorded the quality and location of pain. The slump test showed high sensitivity and moderate specificity in identifying patients with neuropathic pain. Adding the criteria of ‘pain below the knee,’ increased the specificity to 100%. Descriptors of pain quality did not improve diagnostic accuracy.

Dr. Shay uses a “hard positive” and a “soft positive” to interpret slump test findings in his patients. “There is pain past the knee (in full slump position) that is partially or totally relieved by cervical extension,” he said. “In the extreme, the patient will not let you get near the full position and that is a positive to me. This usually correlates with a subjective exam of standing or extension preference and avoidance of sitting or flexed postures.”

He uses “soft positive” to describe a patient who “may be positive but the pain does not pass their knee, which can be a sign of neural tension (nerve irritation in the sciatic notch/piriformis region). This may also be a chronic radiculopathy…this is probably still worse with cervical flexion whereas the neck position won’t matter much if pure hamstring tightness is the problem.”

Dr. Shay cautions that when using the slump test to determine readiness to return to activity it is important that pain during the test is completely resolved.

“If they have a positive slump with pain only in the back, I treat this as a centralizing disc that has not completely resolved,” he said. “Too many times I have seen an acute disc treated with injections which centralizes pain to the low back, and they attempt to return to activity. They seem to always come back. I want complete resolution of the slump prior to return to play.”

Penny Goldberg, DPT, ATC

Penny Goldberg, DPT, ATC earned her doctorate in Physical Therapy from the University of Saint Augustine and completed a credentialed sports residency at the University of Florida. She is a Board Certified Clinical Specialist in Sports Physical Therapy.

Penny holds a B.S. in Kinesiology and a M.A. in Physical Education from San Diego State University. She has served as an Athletic Trainer at USD, CSUN, and Butler University.

She has presented on Kinesiophobia and differential diagnosis in complicated cases. Penny has published on returning to sports after ACL reconstruction and fear of movement and re-injury.

Outside of the clinic, Penny enjoys traveling, good cooking with great wine, concerts, working out and playing with her dogs.