Back in 2016 when I watched “Rogue One” in the theater with my girlfriend at the time, it was so good that we didn’t want to leave our seats yet when the credits rolled. The trailers and teasers that dotted Facebook for weeks before the premiere didn’t spoil anything for me. However, some movie trailers had disappointed me because the actual movies weren’t as awesome or as “truthful” as the trailers had depicted. The same can be said about scientific abstracts of a research paper because they don’t tell the whole story and may not accurately reflect on what the full paper actually says.

In social media discussions and debates, some people just read the abstract and puts it online to support or refute a statement or opinion. Sometimes the studies they post do not conclude or find what they had believed. Thus, they shoot their own foot.

Scientific abstracts give you a preview of the research so you can decide if you want to spend your day reading the entire paper or not. Like your favorite fiction novels, research papers provide background information (Introduction), a setting that presents the cast and background of the story, (Method), a climax (Results), and a resolution or ending (Conclusion). Sometimes what is mentioned in the full paper does not get highlighted in the abstract, which can give you a false impression about the research.

Researchers in a 1999 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association randomly selected 44 articles from five major medical journals, including JAMA itself, the New England Journal of Medicine, and the Lancet, between mid-1996 to mid-1997. The authors found that 18 to 68 percent of the studies’ abstracts were inconsistent with the article’s body, including the tables and data.

A French systematic review of 105 studies on randomized-controlled trials in rheumatology found that almost 25 percent of them had disagreeing results and misleading abstract conclusions, especially those with negative results.

More studies in the field of pharmacology and osteopathy also find inconsistencies and high risk of bias within a bundle of randomized-controlled trials. In the 2004 study published in Annals of Pharmacotherapy, almost a quarter of the 243 studies selected from seven pharmacology journals had “omissions” in the abstracts. “Evaluation of these abstracts identified 60 (24.7%) abstracts containing omissions; 81 (33.3%) abstracts contained either an omission or inaccuracy. A total of 147 (60.5%) abstracts were called “deficient.”

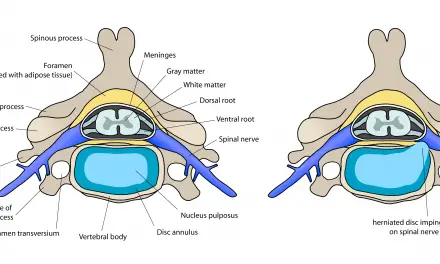

In a 2012 osteopathy study, about 28 percent of the 60 abstracts had a low risk of bias. The authors concluded that many of the studies had too small sample sizes in which the effectiveness of spinal manipulation have any clinical significance.

Finally, at 2019 systematic review of 66 systematic reviews (9 Cochranes, 57 non-Cochranes) on low back pain found that eight out of ten reviews had “inconsistencies.” The Cochrane Reviews had higher rates of consistency compared to non-Cochrane ones. The authors said most of these scientific abstracts on physiotherapy interventions for low back pain had a “spin,” which was determined by a checklist and analysis.

The checklist of items include whether the conclusion supports the intervention even when the data does not indicate so, selective reporting to exaggerate the data, and whether the conclusion is based on “non-statistically results” with huge confidence intervals. However, the authors warned that their checklist is not “fully tested for its measurement properties,” and their results “should be interpreted with caution.”

“We advise readers to read beyond the abstract when using systematic reviews to guide practice. Journal editors and peer reviewers may consider: following and checking both the full text and abstracts reporting checklists, and ensuring that abstracts are free of spin of information,” they wrote.

Video: Why higher confidence intervals increase chances of getting more errors.

What should be in a scientific abstract?

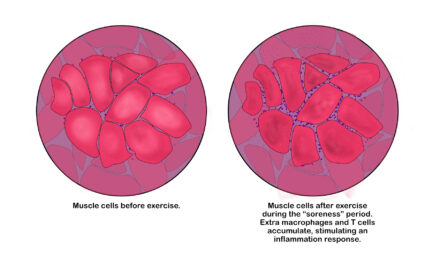

While I didn’t find any similar reviews for massage therapy or exercise, we can tentatively presume that we may likely find misleading abstract conclusions and data if we were to randomly select trials from different publications. So can we do to reduce bias in our own reading and interpretation of a research paper? What should we look for when reading an article?

Dr. Neil O’Connell, who is a researcher in the Centre for Research in Rehabilitation, Brunel University, West London, U.K., highlighted that one or two sentences in an abstract conclusion cannot completely and accurately summarize what a whole paper says. Sometimes we may need to be cynical when interpreting a paper:

Introduction: In which the authors seek to justify the importance of their research by cherry picking any supporting evidence and ignoring the rest.

Discussion: In which the authors seek to interpret the results in a way that does not challenge their pre-existing worldview by jumping through a selection logistical hoops.

Conclusion: In which the authors try to give you a take home message consistent with their pre-existing worldview.

Methods: One of the important bits.

Results: The other important bit (often with parts strangely missing).

In 2004, a group of researchers published a guide to help us identify flaws in research studies and papers. They highlighted six things to consider when you read research papers:

1. Read only the Methods and Results sections; bypass the Discussion section;

2. Read the abstract reported in evidence based secondary publications;

3. Beware faulty comparators;

4. Beware composite endpoints;

5. Beware small treatment effects;

6. Beware subgroup analyses.

As many researchers would agree, reading and understanding what the authors did (methodology) and what they found (results) are the most important parts if you want to know whether the conclusions and premise (introduction) are accurate or not. Conclusions and results that are driven by flawed methods do not accurately reflect the premise, which can lead to flawed ideas and treatments. Don’t put the cart in front of the horse.

Of course, not all scientific abstracts are inaccurate. The introduction of the paper should describe what is known and unknown about the topic, cover any controversies, and provide a hypothesis that the study tests. The methodology section describes how the experiment is set up, the sample population (size, demographics, method of selection, etc.).

The larger and more specific the population is, the less bias it has and better represent the general target population. For example, a study of 2,000 elderly men from with knee pain would be a more accurate representation of that general population than having just 20 or 200 of the same subjects.

The results section reviews what the authors found, usually with loads of statistics, math, and graphs. While this may be too technical for some of us, taking a basic course in statistics can help us interpret the data better because this can determine whether the conclusion reflects on what the data says and how well the method is set up.

The discussion and conclusion sections should not only summarize the findings, but also critically ask questions about them, discuss limitations of the study, and whether the hypothesis is supported or not. The authors should not cherry-pick their position from the results.

Although scientific abstracts do not always tell the whole story accurately, we should remain skeptical about what we read there until we have read the entire paper, even if the abstracts’ conclusion agrees with our opinions. Even systematic reviews and meta-analyses, which are often regarded as having high quality evidence and low risk of bias, can draw misleading conclusions and misinterpreting data. If what goes into the review (data) is garbage, then the results will come out as highly biased garbage.

“We shouldn’t fall into the trap of thinking that since research is flawed, we’re better off relying on clinical experience. These two studies are a good example of how science, unlike opinion, is self correcting. If these studies tell us anything it’s that those poor, neglected methods and results sections is where you’ll find the real gold.” ~ Dr. Neil O’Connell

Further reading: Six Details to Ask When Reading Massage Therapy Research

A native of San Diego for nearly 40 years, Nick Ng is an editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine, an online publication for manual therapists and the public who want to explore the science behind touch, pain, and exercise, and how to apply that in their hands-on practice or daily lives.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a B.A. in Graphic Communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014.

When he is not writing or reading, you would likely find him weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, or exploring new areas to walk and eat around Southern California.