Pes anserine bursitis is an inflammatory condition affecting the bursa located between the tibia and the three tendons of the hamstring muscle at the inside of the knee.

Pes anserine is Latin for “goose’s foot” because of its shape. It can result from direct trauma, overuse, or as part of the secondary symptoms of another disease.

How common is it?

It’s difficult to determine the frequency of pes anserine bursitis due to the considerable overlap with other knee conditions. A study that drew on data from more than 4,200 adults found that the most common people with osteoarthritis were present in more than 90% of cases.

A smaller study of 24 patients (ages 30 to 50 years) found 2.5% of adults with medial or posteromedial knee pain had pes anserine bursitis.

Pes anserine bursitis may also be a secondary diagnosis as it has been associated with osteoarthritis and being overweight. One series of radiographic images found knee osteoarthritis in 93% of patients with diagnosed pes anserine bursitis.

Among 96 diabetic patients with non-insulin dependent diabetes in one study, 34% had pes anserine bursitis while there were no cases in the non-diabetic control group. Another study also found a prevalence of nearly 30% of 48 patients with type 2 diabetes. Thus, osteoarthritis and diabetes would be the primary diagnosis, as pes anserine bursitis occurs secondary to the other conditions.

Pes anserine bursa anatomy and biomechanics

The pes anserine bursa, one of 13 bursae around the knee joint, is located between the tibia and the tendinous attachments right below the middle of the knee joint. It also provides the medial side of the knee some stability.

Pes anserine is formed by the conjoined tendons of the gracilis, sartorius, and semitendinosus muscles as they form a broad structure that covers the medial part of the knee.

During knee motion, the pes anserine bursa is stressed during active flexion and adduction as the hamstring and adductor muscles contract and compress the bursa between the soft tissues and the bone. When pes anserine bursitis is present, the patient experiences pain with repeated knee flexion and extension (such as with stair climbing).

There also seems to be a relationship between pes anserine and overweight women. Women tend to have a wider pelvis which leads to a larger Q-angle, which can be associated with tight adductors and weak abductors.

Knee stability can be compromised by anatomical anomalies, arthritic changes, overuse injury, or trauma. A bony junction called the screw-home mechanism provides knee stability.

When the knee is unlocked, it relies on soft tissue to provide stability. The anterior (ACL) and posterior cruciate ligaments (PCL) primarily resist sliding of the tibia on the femur. Their secondary function is to resist rotational forces at the knee.

The medial (MCL) and lateral collateral ligaments (LCL) resist valgus and varus stress, respectively, and also assist in resisting rotation.

There are two menisci wedged between the tibia and fibula. The medial meniscus is “C” shaped while the lateral meniscus more closely resembles an “O.” The larger medial meniscus is prone to injury due to its shape. The menisci disperses loads to spare wearing of the articular cartilage on the bony surfaces of the tibia and fibula. The medial meniscus is firmly attached to the medial joint capsule and moves less during motion than its lateral counterpart.

Pes anserine bursitis causes

A bursitis often refers to the irritation of any bursae, which are hollow structures found throughout the body in areas of increased friction between soft tissues and bony structures. Inflammation of the pes anserine bursa is caused by:

- Excessive friction from valgus or rotatory stress

- Degenerative joint disease, such as rheumatism and osteoarthritis,

- Direct trauma

Secondary causes that are associated with pes anserine bursitis include:

- Obesity

- Joint overuse, such as repetitive motions

- Altered gait patterns

A changed gait pattern to avoiding knee pain could create lasting knee flexion as well. In repetitive activities, this flexed position can become problematic as it changes the wear patterns of the joint surfaces and doesn’t allow the normal metabolic processes that are part of soft tissue health to occur. In these cases, restoring full knee extension may be an easy and effective management strategy.

Pes anserine bursitis diagnosis

The best tests to confirm the presence of pes anserine bursitis are:

- Tenderness to palpation

- Pain with active motion (the contracting muscle compresses the bursa)

- Passive motion (the lengthened muscle compresses the bursa)

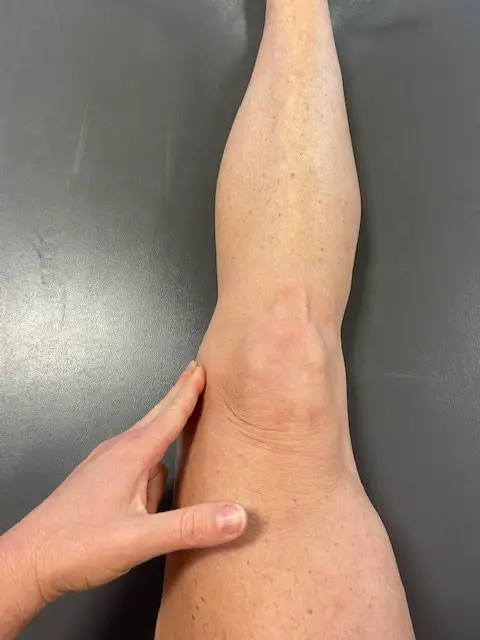

(Photo: Penny Goldberg)

Since the gracilis. sartorius, and semitendinosus muscles flex the knee and resist tibial rotation when you cross one leg over the other, this position can be a useful diagnostic exam where pain is a positive sign. Also, you might report weakness, stiffness, and decreased range of motion around your knees.

Tenderness is a cardinal sign of bursitis while inflammation may or may not be present. Those with an established diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis should be screened for pes anserine pain and bursitis.

The classic symptoms of pes anserine bursitis include:

- Swelling and tenderness of the medial knee

- Diffuse medial knee pain, which may be located along the medial joint line

Differential diagnosis should rule out MCL injury, medial meniscus injury, Baker’s cysts, and semimembranosus bursitis.

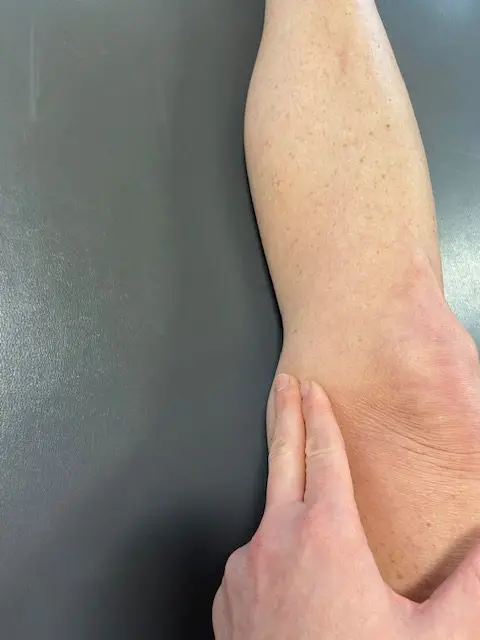

Imaging isn’t typically required. The key to making this diagnosis is the location of tenderness. Pes anserine bursitis will be tender to palpation on the proximal medial tibia—three to five centimeters distal to the medial joint line of the knee.

Medial joint line palpation. (Photo: Penny Goldberg)

Medial joint line palpation , close up. (Photo: Penny Goldberg)

Additional diagnostic criteria nor has the efficacy of using palpation to diagnose bursitis been established. Both magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and diagnostic ultrasound can show other causes of local swelling, joint effusion, and rule out alternative diagnoses.

All that said, the diagnosis of pes anserine is not without controversy. Historically, MRI studies that showed the presence of fluid within the pes anserine bursa in patients with medial menisectomy lent to the validity of bursal involvement.

However, Uson et al. examined ultrasounds of 37 patients with diagnosed pes anserine bursitis revealed that bursal enlargement was only present in two patients.

More recently, Unlu et al. studied 48 patients with type 2 diabetes and clinically diagnosed pes anserine bursitis found that less than 10% had ultrasonographic evidence of bursal swelling or pes anserine tendinopathy.

Participants in this study with pes anserine bursitis or tendinitis had medial meniscopathy, osteoarthritis, popliteal cysts, and suprapatellar recess effusions more often than participants in the control group.

It’s possible that the pes anserine bursa is incorrectly identified as the faulty structure in these cases but a more plausible explanation for this pain has yet to be presented.

As with most knee pain conditions, the differential diagnosis for pain in the region of pes anserine is broad. Infectious pathology and gout should be ruled out at the initial examination. For example, compression to the saphenous nerve (likely through the adductor canal) can cause medial knee discomfort absent any other pain or symptoms.

Treatment and recovery time

Treatment for pes anserine bursitis typically follows the recommendations of other musculoskeletal conditions:

- Rest

- Ice

- Anti-inflammatory medications

Patients who are overweight or obese may also be deconditioned and may benefit from a program that addresses general strengthening (specifically to the quadriceps) to assist in long-term symptom improvement.

A 2016 study examined whether the presence of pes anserine bursitis was associated with greater impairment and disability among 176 patients with knee osteoarthritis. The study also evaluated the effectiveness of local corticosteroid injection versus physical therapy. About 47% also had pes anserine tendino-bursitis.

Patients with and without the condition were separated into two groups. Group A received a hot pack, ultrasound, and transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation (TENS) for two weeks while Group B was given a corticosteroid injection to the most tender aspect of the pes anserine region.

Patients with osteoarthritis and pes anserine pathology had higher pain scores and more functional disability. Both physical therapy and corticosteroid injections were effective treatments for pain and no difference was found in functional ability between the two groups after treatment.

As a physical therapist, I would be remiss if I didn’t point out that a physical therapy session consisting of heat, ultrasound, and electrical stimulation is not evidence-based and should not be considered “normal.”

A similar study compared the use of Kinesio tape to physical therapy (hot pack, electrical stimulation, phonophoresis) and found both were effective in the treatment of pain with taping being the better option. It’s important that readers critically evaluate research methods rather than simply reading titles and conclusions.

In both of these studies, it’s possible that the results would’ve been different if physical therapy had addressed muscle tightness, weaknesses, disability, and pain levels rather than merely using passive modalities.

A study of corticosteroid injection alone in patients with osteoarthritis and pes anserine tendino-bursitis demonstrated that injection may be an effective first-line treatment for this condition.

Another study of 44 patients who received either naproxen or injection found that at one-month follow-up, 58% of those taking naproxen reported significant improvement with 5% of the condition resolved, while 70% of those who were injected were significantly improved and 30% of the condition had resolved.

As with any medical condition, musculoskeletal or otherwise, readers should consult with a physician or qualified medical professional to determine the best course of treatment for their condition. This article should not be considered a substitute for professional advice or care.

Pes anserine bursitis exercise

There aren’t many studies that evaluate exercise for the treatment of pes anserine bursitis. One case study describes the use of “ACL injury prevention exercises” in pes anserine syndrome.

The patient had decreased lower leg strength, gait deviations, lack of full knee flexion, and pain. Exercises that were used include:

- Dead bugs

- Hamstring eccentrics

- Squats

- Glute bridges

- Single-leg stance with toe taps

After eight weeks, the patient showed improvements in movement and had less pain and tenderness. The eight-week timeline may not be desirable in cases where pain is significantly limiting other aspects of life.

In that case, corticosteroid injection can be useful as an adjunct to therapy as it allows patients to perform both activities of daily living and rehab exercises that would otherwise be intolerable.

Pes anserine bursitis prevention

There are no proven methods for decreasing the likelihood of getting pes anserine bursitis. As with most joint conditions, maintaining a healthy weight and an active lifestyle may decrease the risk of developing pes anserine bursitis. If you already have type 2 diabetes, a healthy diet and exercise can assist with disease management which may prevent or delay the onset of other joint and muscle issues.

Massage therapy and pes anserine bursitis

Direct massage therapy for pes anserine bursitis is not well-supported in the scientific literature as patients with this condition are typically tender at the medial aspect of the knee and are unable to tolerate even light pressure on the area. But there’s a role for massage therapy in treating such conditions.

A study comparing dynamic soft tissue mobilization and classic soft tissue mobilization techniques found the dynamic approach improved hamstring flexibility more in healthy men.

After the massage, those in the dynamic group gained an average of three degrees more flexibility than those in the standard or control groups. Therefore, dynamic mobilization techniques may be an effective treatment for patients with pes anserine bursitis when hamstring tightness is present.

Several studies have established the efficacy of massage therapy in patients with osteoarthritis. Patients who received Swedish massage had improvements in pain, stiffness, function, and range of motion in three days.

The researchers of that study also examined the use of Swedish massage in 68 patients with knee osteoarthritis and found it to be an efficacious treatment.

It may also be worthwhile to teach patients self-massage techniques to use between massage therapy sessions. A 2013 randomized control trial looked at the outcomes of self-massage intervention to the quadriceps muscles group.

While pes anserine bursitis is less common than other types of knee pain, it shouldn’t be overlooked because missing this diagnosis can result in prolonged pain and unnecessary treatments.

Penny Goldberg, DPT, ATC

Penny Goldberg, DPT, ATC earned her doctorate in Physical Therapy from the University of Saint Augustine and completed a credentialed sports residency at the University of Florida. She is a Board Certified Clinical Specialist in Sports Physical Therapy.

Penny holds a B.S. in Kinesiology and a M.A. in Physical Education from San Diego State University. She has served as an Athletic Trainer at USD, CSUN, and Butler University.

She has presented on Kinesiophobia and differential diagnosis in complicated cases. Penny has published on returning to sports after ACL reconstruction and fear of movement and re-injury.

Outside of the clinic, Penny enjoys traveling, good cooking with great wine, concerts, working out and playing with her dogs.