Muscle soreness, sometimes called “delayed onset muscle soreness” (DOMS) is a dull, achy pain that you may have experienced after a hard workout, especially if you’re not used to exercising. It’s a “functional muscle disorder” without any obvious visible signs of muscle structure damage due to overexertion and eccentric muscle contraction, according to the 2012 Munich consensus statement. Muscle soreness often occurs within several hours to one day after exercise and can last from two to three days to seven to ten days.

Along with muscle topicals, heat and cold therapies, and stretching, massage therapy is often used—and touted—to get rid of muscle soreness. Despite such claims, current scientific evidence weaves a different story about what causes muscle soreness, and what you should do about it.

What causes muscle soreness?

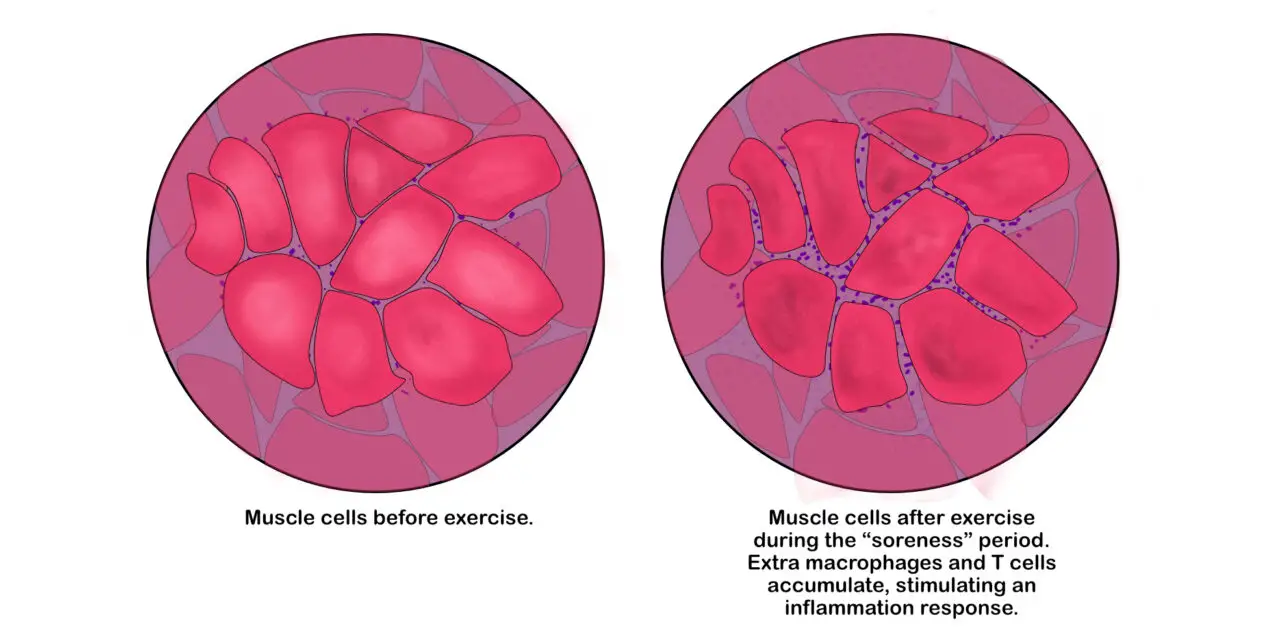

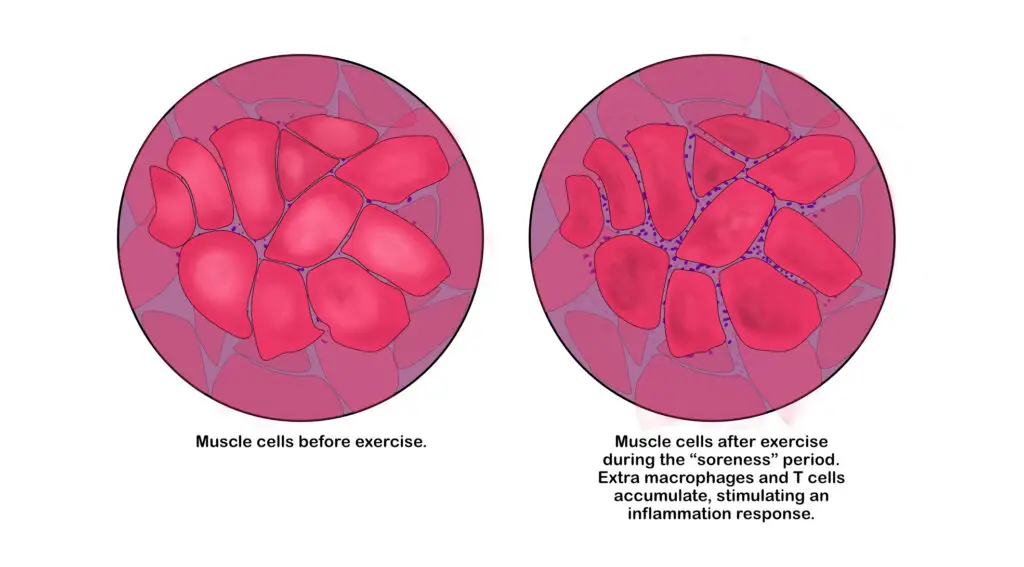

Muscle soreness is primarily caused by damage to the muscle tissues and nerves within a muscle, specifically the sarcomeres in the myofibrils, which are the rod-shaped bundles of muscle cells. Eccentric muscle contractions have been shown to cause such damage to a greater degree than other types of muscle contractions, leading to inflammation and an increased rate of protein breakdown in muscle cell membranes.

Basically, eccentric contraction is the lengthening of your muscles under a tension that is greater than the shortening of your muscles (concentric contraction). A classic example would be the lowering of a heavy dumbbell when you do a biceps curl.

Inflammation in muscles occurs when white blood cells accumulate within the exercised muscle. (Illustration by Nick Ng)

Although the mechanisms of eccentric contraction are less understood than concentric and isometric contractions, one hypothesis—based on a study of frog muscles—suggests that the former requires twice the amount of cross bridges of the contractile proteins, actin and myosin, during the lengthening process.

Whether this extra work may contribute to muscle soreness is debatable, however, some researchers have pointed out that the sarcomeres get weaker and overstretched with repetitive eccentric contractions, which temporarily changes the normal cross-bridging. This likely leads to sarcolemma, increased inflammation, and disruption of the neural communication between the nervous and muscular systems.

Does lactic acid cause muscle soreness?

You may often hear that lactic acid is the main cause of muscle soreness, but that isn’t true. The myth that massage therapy can help you get rid of lactic acid because they are “toxins” is still prevalent among massage culture. Among personal trainers, this is also no exception since many believe that lactate or lactic acid is a primary cause of the muscle “burn”that you get after a workout.

Contrary to this popular belief, lactate actually reduces or buffers the rate of acidosis build-up and is not a contributor to acidosis and muscle soreness. It’s also a form of fuel that your body recycles and reuses during bouts of high-intensity exercise.

First, the terms “lactic acid” and “lactate” are often used interchangeably, but they are slightly different compounds as part of your metabolism.

“Everybody has heard of lactic acid, but not everyone has heard of lactate,” said Dr. Michael Lindinger, who taught human physiology at the University of Guelph for 25 years. He described lactic acid and another metabolic compound, pyruvic acid, as “dissociated compounds,” which means they are broken apart on a molecular level to form an acid (+) and base (-). But this form is uncommon because it’s unstable.

“The term lactic acid and pyruvic acid arise from research and studies published more than 100 years ago,” Lindinger said. “At the time, the understanding of biochemistry was in its infancy, and the physical and chemical properties of lactic acid and pyruvic acid in the body in living cells was poorly understood. All of the early research was conducted using dead or dying muscles.”

Lindinger said that academics and clinicians use the terms lactic acid and lactate as if they’re the same things (same with pyruvate and pyruvic acid). Back then — and probably now — it was a way for researchers to make physiology easier for the public to understand.

Lactate is produced in all organs in your body, with your liver and kidneys being the top two producers when you are at rest. During exercise, skeletal muscles are the largest manufacturers of lactate as a result of breaking down glucose for energy, especially during high-intensity, short-duration exercise like sprinting and Olympic lifting.

When adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is used for energy, it converts to adenosine diphosphate (ADP) with a released proton, which has a positive charge. When there’s enough oxygen to meet muscle contraction demands, no proton is in excess within the cell since the extra protons in the cells’ cytosol get shuttled into the mitochondria. Theoretically, this accumulation of protons is thought to cause acidosis, but this idea contradicts what research says.

Can nerve damage cause muscle soreness?

It’s possible that nerve damage inside the muscle itself can also cause muscle soreness. A team of Hungarian researchers, led by Dr. Balazs Sonkodi of the University of Physical Education in Budapest, proposed that free nerve endings inside the muscle spindles of a skeletal muscle gets overcompressed during repeated bouts of eccentric contractions. In their hypothesis, muscle soreness is a “safety function” that prevents you from re-engaging the strenuous exercise that may further damage your tissues.

Muscle spindles help us sense where our body parts are positioned and moved in our environment, even when we aren’t looking at it. They contain intrafusal muscle fibers that are innervated by sensory and motor neurons and share innervations with the sympathetic nervous system.

Muscle spindles also harbor Type Ia and Type II sensory fiber nerve endings. Type 1a gauges the rate of muscle stretching, while Type II senses touch and provides proprioception.

Based on their hypothesis, if you were to lift weights with an emphasis on the lowering phase of the muscle contraction, you’re also compressing the fluid cavity surrounding the intrafusal muscle fibers which further squishes the nerves. And if you’re not used to doing strenuous exercise, your sympathetic nervous system kicks in during exercise (fight or flight), which suppresses the symptoms of any muscle soreness.

Combined with microtears in the muscle tissues and inflammatory responses in the spinal cord and brain, within hours after you stopped exercising, the sympathetic nervous system tapers down to the point where you begin to feel the symptoms of DOMS.

Does massage get rid of muscle soreness?

Muscle soreness from massage therapy can vary among each person. It can last for a few hours or days or it may provide almost no relief at all. Sometimes massage might even make you feel more sore!

It’s really hard to say why some people feel better after a massage and some don’t. Stress, medications, prior experience and expectations to treatments: all of these factors among many can affect the outcome. Current science reveals a little bit about whether massage works or not.

Researchers from the University of Poitiers in France concluded that massage therapy “seems to be the most effective” for DOMS and perceived fatigue. Led by exercise scientist Olivier Dupuy, the team divided 99 qualified studies into four categories: 80 for DOMS, 17 for perceived fatigue, 19 for inflammatory markers, and 37 for muscle damage markers. Some of these studies overlap more than one of these categories, and all outcomes were measured after one treatment.

They compared each recovery method to see their effects for muscle soreness, including massage therapy, cryotherapy, compression garments, low-intensity exercise, stretching, electrical stimulation, and various types of water therapy. After they pooled and analyzed the data, they found that massage therapy “to be the most powerful procedure that induced significant benefits of DOMS and perceived fatigue, regardless of the subjects (athletes, sedentary subjects)” with water immersion and cryotherapy trailing behind massage for reducing inflammation.

Compared to massage, compression garments and water immersion had a lesser degree of positive effect. “Active recovery, contrast water therapy and cryotherapy had a positive impact only on DOMS, whereas massage combined with stretching also induced benefits in perceived fatigue. The other techniques did not have a significant impact on DOMS or fatigue but had some effects on [inflammatory marker] concentrations in the blood,” the researchers reported.

They also found that massage therapy is the “most effective” treatment for reducing certain inflammatory markers, such as creatine kinase and interleukin-6 in the blood after exercise, which may reduce muscle damage and promote faster recovery.

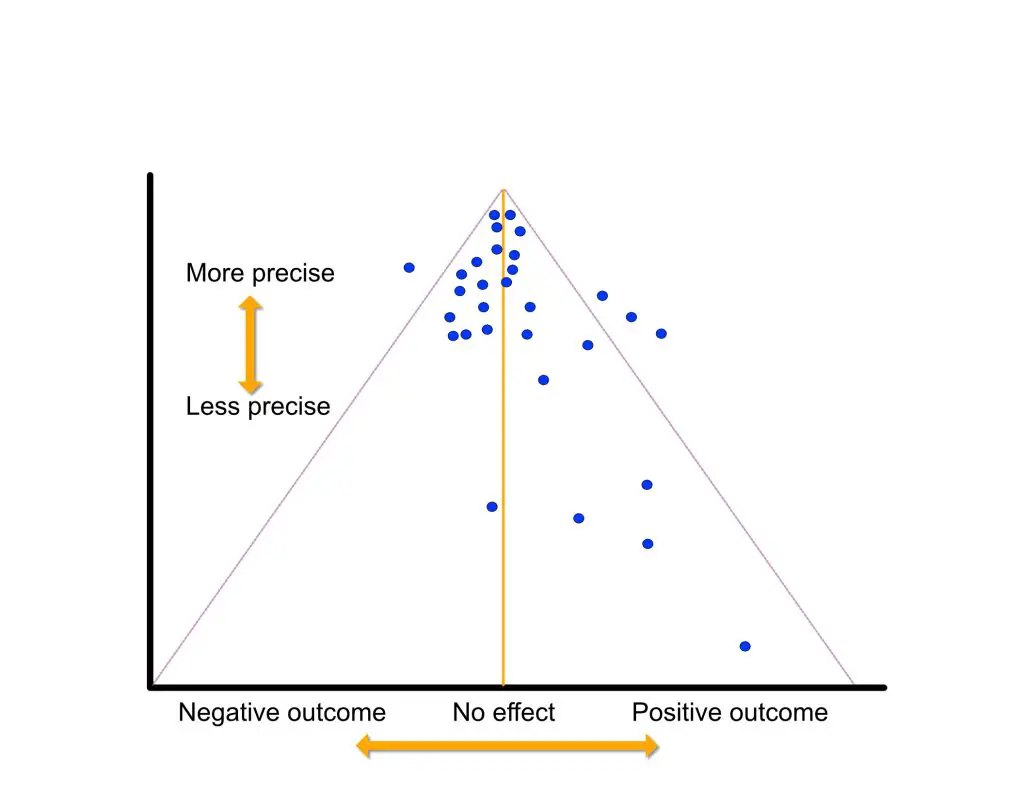

Before you yell that massage therapy “works” for muscle soreness, there’s a deeper plot than what the conclusion and results say. Physicist and journalist Alex Hutchinson of Outside magazine is like that detective. He pointed out the funnel plot graphs in the study that show the number of studies included, the quality of those studies, and whether the results are. Basically, the funnel plot is like a checklist to see whether publication bias exists in a meta-analysis and systematic review.

Because most of the massage studies included have small sample sizes, the chances of getting a very positive or negative outcome is no better than a coin toss—even if the treatment does nothing. The positive ones would likely get published while negative ones get tucked inside a “file drawer” as the researchers move on to the next project. Therefore, if you Google “massage therapy muscle soreness,” you might see mostly positive results.

Higher-quality studies have more precision and less errors, which are placed on top of the funnel. A few studies have strong positive results but their precision is low compared to those that found small to almost zero effect.(Illustration by Nick Ng)

The horizontal axis of the plot gauges the strength of the results (in this case, positive or negative) while the vertical axis is the precision of the studies. The less precise the studies, the lower on the vertical axis they go.

In this analysis, the higher-quality studies cluster near the top and close to the center line, indicating that most of the interventions included had little or no effect. There are some scattered along the positive side of the funnel plot, but they rank lower in the cluster. In other words, lower-quality studies tend to favor positive results.

Dupuy et al. also described several limitations about their systematic review, which include mixed study designs that make measuring the data and drawing the conclusion difficult and single-blinded studies that can increase the risk of bias among the researchers, subjects, and peer reviewers. Since the therapist who is giving the treatment cannot be blinded, manual therapy research is nearly impossible to be double-blinded. Even if athletes are able to perform after a recovery, the researchers cautioned that it doesn’t always mean that they are fully recovered.

The placebo effect and regression to the mean are likely contributors to most of the studies’ outcomes. Dr. Martin Englund from Lund University recently wrote in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases that the placebo effect and contextual effects “may contribute to the total treatment effect.” But researchers, clinicians, and journalists tend to omit or forget these factors and rave about the positive effects only because of the treatment.

One earlier systematic review from China reported that massage therapy “could be effective for alleviating DOMS, as well as increasing muscle performance after strenuous exercise.” However, all of the 11 studies in the meta-analysis were low in quality, the researchers reported, for similar reasons as Dupuy’s study.

Another study from Portugal concluded quite differently. While the researchers found massage therapy also had positive effects for DOMS, “its mean effect is too small to be considered clinically relevant.”

What helps get rid of muscle soreness?

While many health and fitness experts claim that stretching, taping, massage, and other ways have “worked” for them and their clients or patients or they’ve seen it with their own eyes, science paints a more complex scene when there isn’t a clear-cut answer.

Stretching and muscle soreness

While many people tend to stretch to alleviate muscle soreness, current evidence “does not support nor contradicts the utilization of post-exercise stretching,” according to an international team of researchers in their 2021 study, led by Dr. Jose Afonso of the University of Porto in Portugal.

Among 10 qualified randomized-controlled trials, they found that different types of stretching, such as PNF, passive, and active stretching, aren’t that any better than active or passive recovery, such as stationary cycling and rest, respectively.

While there’s no evidence that stretching impedes muscle soreness recovery, there’s also no evidence that stretching improves an athlete’s recovery level beyond their basal value or within one to four days of exercise, Afonso et al. wrote.

“I believe that post-exercise stretching should be optional: do it if you like it, don’t do it if you don’t like it,” Afonso said, who emphasized that there’s a psychological component to stretching.

While there’s no evidence that stretching impedes muscle soreness recovery, there’s also no evidence that stretching improves it beyond their base value. (Photo by Nick Ng)

They also emphasized that short-term positive effects “should be balanced with long-term adaptations.” For example, they pointed out that cold-water immersion after exercise accelerated short-term recovery, but it impaired the subjects’ ability to heal their muscles after two weeks of training when they discontinued their treatment.

Other problems with the stretching for muscle soreness research include small sample sizes, different definitions of stretching, different experimental setup, subjects were mostly adults under 40 years old, and relying on measurement of inflammatory biomarkers in blood and tissue.

“Inflammatory biomarkers are not very reliable because there are many non-responders or hypo-responders,” Afonso said. He highlighted that in some people, their creatine kinase, an inflammatory biomarker, concentrations don’t elevate even if there is extreme muscle damage.

“Furthermore, some studies showed improved lactate kinetics, but no relationships with measures of performance,” he said. “However, I would advise caution when stretching post-exercise; personally, I would not do it, but if people like to perform that, better to use low intensity and small durations per position.”

“The problem is that mainstream traditions keep negating the evidence, and many people still believe stretching post-exercise is beneficial for recovery,” Afonso said. “In [Portugal], the situation has been slowly changing in fitness, physiotherapy, and orthopedics, but there’s still a long way to go. Based on the existing evidence, the best advice is probably to keep post-exercise stretching optional.”

Kinesio taping for soreness

Kinesio taping and other similar tapes and methods are often used for reducing pain, “improve” athletic performance, and a hodgepodge of reasons. For muscle soreness, favorable evidence for Kinesio tape seems to be lacking.

Kinesio taping and other taping methods may alleviate muscle soreness, but current research finds that regression to the mean may be a larger factor than taping itself. (Photo by Penny Goldberg)

A group of Chinese researchers from Fujian Medical University investigated this in 2020 and conducted the first systematic review and meta-analysis of Kinesio tape for muscle soreness. Out of eight randomized-controlled trials (five in English, three in Chinese) with a total of 289 participants, Lin et al. Kinesio taping is the most effective if the tape is left on for 48 or 72 hours—not so much at 24 hours.

However, they found that the studies also contain a large number of biases, such as poor allocation concealment (researchers and subjects know who is getting the treatment or not) and blinding of subjects and outcomesMost of the subjects were also young, male athletes, so whether this would apply to other populations is unknown.

Foaming rolling for muscle soreness

Many manual therapists and trainers often recommend foam rolling or using a similar tool to alleviate muscle soreness. However, scientific evidence doesn’t really support this idea.

A 2019 meta-analysis of 21 studies with a pool of 454 subjects found that foam rolling for warm-ups and recoveries are “still in question in both scenarios.” These studies examine the effects of foam rolling and other self-massage techniques for improving strength, sprint, and jump performances.

The researchers found that there was a 0.7% improvement in sprinting after the subjects used foam rolling for warm-ups. While this tiny increment may not be relevant to typical weekend warriors, they said that this may make a huge difference among elite athletes where every millisecond counts—a difference between a gold and silver medal.

Research finds mixed results about whether foam rolling can reduce muscle soreness or not. It depends on many factors, such as exercise experience, type of exercise done, duration of foam rolling, and experiment setup. (Photo by microgen/123rf.com)

For muscle soreness and cooldowns, there’s no evidence that supports or refutes its usage because there “are not enough high-quality and well-designed studies on [foam rolling] to draw any definite conclusions.” Different experimental designs, lack of consistent rolling protocols, and confounding factors (e.g. placebo effect).

With a pool of 49 studies, a 2021 systematic review found similar results. While the researchers also found short-term and small benefits to foam roller before exercise, they found that there may be some similar benefits for pain and stress relief post-exercise.

They stated that foam rolling may reduce arterial stiffness, improve the function of endothelial cells in the blood vessels, and enhance blood flow. However, because of the same limitations as the 2019 meta-analysis stated, these claims should not be taken as the gospel until better evidence supports or refutes them.

Cooldowns and low-intensity exercise

Low-intensity exercises, such as stationary cycling or walking, are often used as part of an active cooldown in hopes of reducing muscle soreness. However, research shows that such a method isn’t that better than passive cooldowns, like using a sauna or just resting on a couch.

Exercise scientists Bas Van Hooren and Jonathan Peake found a few studies in their 2018 narrative review that showed increased blood flow can shuttle metabolic by-products that attributes to muscle soreness, such as cyclo-oxygenase and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor. But these studies use exercises that intentionally provoke muscle soreness, which is rarely used in real-life athletic settings and may not practically apply to training.

They also found “found no significant effect” of an active cooldown for muscle soreness among recreational athletes. One study found that netball athletes reported greater muscle soreness after an active cooldown of jogging within 24 hours after a game, while another study of young soccer players reported to have lower muscle soreness four to five hours after competition after a bout of active cooldown (jogging).

While various factors affect how effective low-intensity exercise can help or not (e.g. gender, exercise intensity and duration), Van Hooren and Peake concluded that low-intensity exercise is “generally not effective for reducing delayed-onset muscle soreness following exercise.”

Does muscle soreness mean muscle growth?

While there’s some truth to the idea that muscle soreness is associated with muscle growth and repair, scant evidence points to bone remodeling and nerve adaptation as potential contributors to such pain.

For example, some rodent and human studies found that several types of protein chains (e.g. CGRP and substance P) proliferates in sensory nerves in a bone fracture, which contributes to higher pain sensitivity.

But muscle soreness doesn’t always equate to muscle growth because some people can still have such growth without the pain.

“If you have muscle soreness, that means you provoked serious aggression to your muscles and other structures. That may lead to overcompensation and maybe muscle growth,” Afonso said. “However, we now know that soreness is not necessary for muscle growth. In fact, if you get sore, you are likely to lose some training sessions or underperform in those sessions.

“So, if muscle growth is possible without soreness, why aim for soreness? Maybe special populations, such as bodybuilders, have to do it, but for most people, soreness should not be targeted.”

Should you get a massage for muscle soreness anyway?

While the current evidence neither favors nor discredits massage therapy as a way to alleviate DOMS, it would be up to you. This would depend on your expectations (e.g. “Yes, massage can help reduce the soreness!”) and prior experience (e.g. “I don’t think it would help because my previous massage was painful.”) If you find it beneficial, book a session. If not, find something else that works for you.

Since muscle soreness is akin to some types of muscle pain, massage therapy may reduce the symptoms temporarily, allowing some people to sleep better, have more confidence in moving, and other outcomes that enhance the effects of massage like a butterfly effect.

Remember that contextual and environmental effects, such as the relationship between the client/patient and the therapist, ambiance of the treatment room, and the words and language used by the therapist can influence the treatment outcome. These factors don’t undermine massage therapy itself. Therapists must consider other factors that influence clients’ or patients’ experience when they communicate with them.

Muscle soreness is one of last frontiers in human physiology that exercise science has yet to explore thoroughly. Just like how researchers used to think that joint popping is caused by the collapse of joint popping a “bubble” within the synovial fluids of the joint, perhaps emerging research in the future would reveal whether such a mechanism is true or not. Meanwhile, we may have to wait for a while since muscle soreness seems to be quite low in research priority in exercise science.

“We strongly suggest that science should abide by the burden of proof,” Afonso and his team wrote. “Until more (and better) data is collected, no case should be built for (or against) post-exercise stretching with the goal.”

Nick Ng is the editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine and the managing editor for My Neighborhood News Network.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a bachelor’s in graphic communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014. In 2021, he earned an associate degree in journalism at Palomar College.

When he gets a chance, he enjoys weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, and exploring new areas in the Puget Sound area in Washington state.