Trigger point therapy is a type of massage technique that is supposed to help alleviate the symptoms or even “get rid of” trigger points.

These trigger points are traditionally thought to be tiny muscle knots or tissue adhesions that cause the sore spots when you press on certain areas of your body, such as your calves or upper trapezius.

Although many people find some relief in trigger point therapy, the mechanisms of how it works is as uncertain as most types of massage. Even the nature of trigger points and myofascial pain syndrome is still as murky as a cup of boba milk tea, despite more than 30 years of research.

Debate around this topic can get heated like the dress color illusion. Proponents of the existence of trigger points claim that trigger points are the cause of myofascial pain syndrome.

By applying certain manual therapy techniques, pressure release, needling, and/or trigger point injections, a manual therapist can “remove” trigger points or at least reduce the pain in the short run.

But there’s a lack of quality evidence that such trigger points exist, as many critics pointed out. Instead of blaming muscle knots or connective tissues, the soreness likely stems from a combination of neural, immunal, and endocrine factors, as some established pain theories suggest.

So how can we make sense of this? Is trigger point therapy any different than other types of massage, like Swedish or deep tissue massage? Do you even need a trigger point massage when the underlying ideas are questionable as the existence of Bigfoot?

If you’re a massage therapist, should you even invest in learning trigger point therapy? Well, let’s take a look at what the evidence says.

What causes trigger points?

The best hypothesis to explain the nature of trigger points is the energy crisis model that was proposed by Dr. Janet Travell in the 1940s. She defined it as “a hyperirritable spot in skeletal muscle that is associated with a hypersensitive palpable nodule in a taut band [of muscle].”

You’ll likely feel tenderness when you press on it and may lead to “referred pain, motor dysfunction, and autonomic phenomena,” according to Travell. Since then, countless modalities have emerged, claiming to directly treat trigger points.

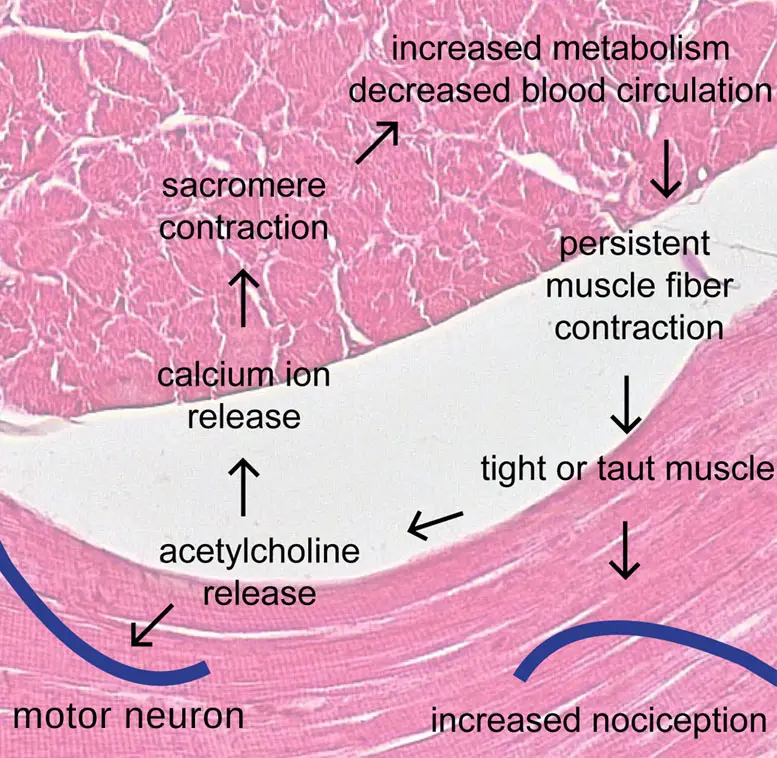

Basically, the hypothesis says that if a muscle fiber is contracted for too long, trigger points can form and myofascial pain develops.

In an editorial published in 1981 in Pain, Travell and Rinzler wrote that when a muscle fiber is contracted under stress, (such as in weight lifting or working at a desk job with your neck forward), this causes the sarcoplasmic reticulum of a muscle cell to release calcium ions to activate the muscle fiber contraction with the help of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the energy currency that fuels our body’s cells.

They wrote that when this happens to a group of bordering muscle fibers, the process can produce a “palpable, tense band of fibers.”

Image: Nick Ng Background image: Berkshire Community College Bioscience Image Library

Prolonged contractions would produce metabolites, which are end products of cell metabolism. Some of these metabolites are acidic, which can sensitize muscle nociceptors and reduce blood flow in the local area. This state of the muscle fibers would be similar to rigor mortis.

And so, this brings about a “vicious cycle” where the sarcomere of the muscle fibers shortens because there’s a lack of ATP and too much calcium ions.

But the calcium cannot be removed because there’s no ATP present to help release the contraction. Travell and Rinzler wrote that the calcium “should eventually diffuse away,” and there may be something else that causes the calcium to linger. This is where the energy crisis hypothesis had gotten its name.

Gerwin, Dummerholt, and Shah expanded Travell and Simons’ work in a 2004 paper by describing the role of various factors that play in the energy crisis hypothesis, such as eccentric and maximal muscle contraction, acetylcholine, pH level, and various chemicals in the muscle tissues.

When the jargon of the expansion is simplified, it sounds similar to what Travell and Simons wrote in 1981. In other words, the underlying principles of trigger points weren’t revised but were sprinkled with details.

Trigger point therapy debate

Before asking whether trigger point therapy works or not, we should understand the debate about the nature of trigger points and myofascial pain syndrome. This can help us decide which treatment is the best or if treatment is even necessary.

“Are these nodules not so much the cause of myofascial pain, but rather normal variations in muscle tissue that are merely coincidentally located over areas of discomfort? With such inconsistencies, this raises the question of whether trigger points exist or not.” ~ Nick Ng

Muscle “knots”

Muscle tissue can feel tight and wiry for many reasons, and sometimes for no apparent reason at all. Almost everyone has experienced a painful area on their body and instinctively pressed on it to find temporary relief. These tender spots are often called muscle knots.

The term “knots” is a useful way to communicate how we feel, but it’s critical to understand that the tissue itself does not get “knotted” in the literal sense.

Knots are not the same as muscle spasms because muscle spasms involve a sudden contraction of an entire muscle. This is what happens with a charley horse, whereas knots are a small, partial contraction of a few fibers in a muscle segment.

To translate it more accurately and simply, knots can behave like a group of microscopic zippers. The contractile elements of the muscle zip closer together and remain active in a specific area of that muscle, and this can sometimes cause it to feel tight or stiff.

They get into this state because the nerve responsible for stimulating them is firing in a way that is causing a cluster of them to “zip” closer together. So a knot cannot exist without a nerve signal.

This is why receiving a massage to help “release knots” isn’t the same as mechanically untangling ropey-feeling muscles, though it may certainly feel that way on the receiving end.

It’s more accurate to say that the stimuli from the massage is sending a signal to a nerve or a bundle of nerves.

Then the nervous system processes the touch stimuli being received. This can tell the nerve that is communicating with the knot to unzip a bit, which helps relax the muscle fibers.

The key is to figure out why the nervous system is generating a knot in the first place. Certain knots might be associated with pain and others are not at all.

Although a knot may be associated with discomfort, often these nodules may serve a beneficial purpose. They can support muscle patterns that are commonly used to execute movements or tasks.

For example, a golfer’s dominant side will likely have more “knots” than the non-dominant side because there’s more habitual activity in those muscles the body has been conditioned to execute.

This is also why knots may or may not be associated with discomfort. People will tend to notice knots more only while they are experiencing aches, even though the nodule might still be present during pain-free periods.

If the muscle fibers aren’t knotted in any way, mechanically pushing into these areas by some external means, usually manually or with a tool, doesn’t technically “release” the area in the way we might imagine. How we think of the mechanism makes a difference in how such issues may be addressed more effectively.

No consistent diagnosis of trigger points

Diagnosis of myofascial pain syndrome has been shown to be inconsistent among different manual therapists. A group of British researchers, led by Dr. Elizabeth Tough from the University of Exeter, reviewed 93 qualified research on the diagnosis of myofascial pain and trigger points.

They said the reliability of the diagnosis is “varied and inconsistent” because of a lack of “gold standard” in diagnostic criteria which allows clinicians to “accurately and consistently define a case of [myofascial pain].”

They found 19 different criteria to diagnose a trigger point. That’s a lot of inconsistencies.

Common diagnostic criteria include “tender spot in a taut band,” predicted pain referral pattern on tender spot palpation,” and “local twitch movement.” However, only 15 percent of the researchers used these factors to diagnose.

Trigger points are usually asymptomatic, meaning that these tight nodules are also found consistently and abundantly in people who don’t report any type of musculoskeletal pain.

This raises the question: are these nodules not so much the cause of myofascial pain, but rather normal variations in muscle tissue that are merely coincidentally located over areas of discomfort?

With such inconsistencies, this raises the question of whether trigger points exist or not.

Breaking fascia and tissue adhesions

Fascia is another tissue assumed to be involved in myofascial pain syndrome. “Myo” is the Greek root word for muscle, and fascial refers to fascia. This is the connective tissue layer below the skin layers that also covers the muscles and other tissues.

In manual therapy, there’s a common belief that tight or wound up fascia is also contributing to myofascial pain syndrome and movement restrictions.

In some schools of thought, it’s also believed that the fascia can get “stuck” or “glued” to muscle tissue. This is referred to as an adhesion and is also often blamed for myofascial pain and decreased range of motion.

There are countless approaches aimed at releasing the fascia or “breaking up fascia and adhesions,” but with the updated data, the idea that fascia is responsible for myofascial pain syndrome is becoming implausible.

Soft tissue manipulation does not generate enough force to permanently stretch or change fascia. One study by Dr. A. Joseph Threlkeld found that in order to create permanent change in the tissue, you need to break collagen fibers.

This type of force is capable of causing extreme injury and requires thrust techniques outside the scope of practice of massage therapists. Even that approach is questionable.

The idea of breaking up adhesions has also come under fire. Dr. Greg Lehman said, “I don’t know what an adhesion is. It makes no sense. If it is scar tissue, then there is no way you are breaking it up with your hands. Not possible.

“Surgeons use knives for this. Is it some stickiness between tissues? Well, don’t worry about it. When you move, warm up, or strength train, it will go away. Welcome to viscosity land.”

Also, this incorrect way of thinking has led to unnecessary pain after a trigger point therapy or other aggressive massage sessions where manual therapists use unnecessary, and sometimes injurious, amounts of pressure that don’t affect fascia or break adhesions in the way they were taught.

This isn’t to say that the manual approaches don’t work or help but rather to fine tune the explanation as to why they may. In the past 40 years, much more has been discovered about the body, and so has more effective treatments.

There are better explanations for what happens when the manipulation of tissues helps someone feel better or improve their range of motion.

One such explanation is the biopsychosocial model of pain, where pain is a complex and personal experience based on biological, psychological, and sociological factors.

Photo: GBACKSTROM, Wikimedia Commons

Trigger point therapists don’t really agree with what they touch

If you have 100 therapists trying to define what criteria makes up a trigger point or myofascial pain, you would likely have 10 to 20 different opinions. Research in the last 20-plus years reveals so.

One of the first critical systematic reviews found that the reliability of myofascial pain diagnosis is “less than chance”—no better than a coin flip.

This is based on nine qualified studies based on eight articles that examined symptomatic and asymptomatic patients.

The researchers identified major reporting problems in how trigger point research was done, such as lack of blinding of the therapists to clinical information and lack of agreement on what the diagnostic criteria were.

If such a diagnosis has a low reliability and a huge room for error, “an otherwise effective treatment may fail because it is being applied to patients who do not have the condition,” the researchers emphasized.

In 2017, another systematic review followed up on the trigger point literature and found similar results. There was still no “gold standard” of diagnosing myofascial pain or identifying trigger points, and the reliability is still no better than a coin toss.

In reference to trigger point injections with low reliability, the researchers asked, “How certain am I that I am actually injecting a [trigger point]?”

How does trigger point therapy work?

Although trigger point therapy doesn’t untangle muscle knots, release fascia, or break up adhesions in the literal or mechanical sense, it can still offer some pain relief.

The processes by which relief is achieved can be better explained with modern pain science concepts.

One of these can be found in the gate control theory of pain, which was later expanded into the neuromatrix theory of pain. These explanations fill in the gaps left by the more simplistic, yet inaccurate trigger point model.

These studies reveal that pain is not being generated by or from the tissues, but is rather an interpretation of any stimulus that might be coming from the nervous system.

Oftentimes, these signals can be ignored if the brain doesn’t consider them a threat, which is why some nodules may correspond to sites of pain while others do not.

Tension in the form of nodules often presents in areas that require additional muscular support or readiness. This can be seen in the example mentioned early with the golfer who likely has more nodules present on their dominant side.

If we consider the effects of how psychological stress translates into neurological impulses, it’s easier to understand why stress from daily life can also transform into physical tension that has nothing to do with muscular dysfunction or fascia.

The nerve impulses that go out into the tissues, can tell muscle fibers to contract or to return to a relaxed state. They can also report information about the tissues and the environment back to the brain.

This input and output of information is a two-way highway from the nervous system out into the tissues, and vice versa. Touch can be one of the ways helpful information is introduced and transformed into a stimulus.

So when an area is pressed, the good-feeling touch sends a message to the nerve(s) associated with the muscle pain. If the brain interprets the tissue is supported, this often allows the area to lay down its “guard” and “let go.”

If someone is experiencing myofascial pain syndrome, it’s crucial to consider all other factors of life that might be contributing to their experience of pain.

Outside of any obvious tissue stressors, such as strenuous use of the body as well as not having enough activity, factors such as psychological stress, beliefs about what might be causing pain, depression and anxiety, and sociological factors like economic status must be taken into account.

All of these offer a clearer picture as to why one person with a trigger point in their calf experiences pain, when someone with a seemingly similar presentation does not.

There has been a recent link discovered between the nervous system, immune system, and endocrine systems that might also be a factor parading as myofascial pain syndrome.

These combined systems have been termed the neuroimmunoendocrine system, which adds even more complex layers to myofascial pain syndrome.

How to perform trigger point therapy

Trigger point therapy often consists of pushing, squeezing, or compressing over an area that feels taut or painful. Pressing directly into the muscle tissue through the skin is known as ischemic compression and can sometimes relieve muscle tension and discomfort.

Trigger point charts often associate common areas of pain or discomfort, and they’re often used as a visual aid or reference. These charts illustrate general patterns and regions of pain that may seem to stem from a particular nodule.

However, these trigger point charts are not real-life representations of the nervous system referral patterns, as these present uniquely in individuals like fingerprints.

Even so, they can be helpful for beginners who are getting acquainted with musculoskeletal pain presentations, but these ideas should not be considered definitive or set in stone.

A therapist will zero in on the area where pain is felt using ischemic compression. This involves maintaining comfortable pressure from three or more seconds at varying degrees and angles. You can do this to yourself by manually pressing into the area of discomfort with your thumbs or fingers.

This can also be done with the aid of a tennis ball or a similar object. If you’re unsure about where to apply compression, a trigger point chart can be a good place to start.

One can address the areas highlighted on the chart and modify as needed. It’s true that referral sensations may be experienced, and that is normal. These sensations can change or seem to “move around.”

When applied correctly, this type of compression appears to slightly whiten the skin beneath it. This happens because blood is temporarily pushed out of the vessels. The idea behind this approach is that when fresh blood rushes back in, it supplies the nodule with oxygen which in turn helps the trigger point “release.”

One of the most common areas where trigger points are present is along the upper trapezius muscle. This is the area most people point to when they say they feel shoulder tension. It’s an instinctual area to reach for and want to squeeze when stress is felt.

Trigger point therapy is also used in the area of the lower back and gluteal region to address back and hip pain. This is an easy to access area for self-massage.

Many people lay on a tennis ball or a rolled up sock placed over the area and achieve pressure that way. Sometimes a foam roller is used for a broader point of contact

The tissue in these areas are more dense and can absorb more pressure, but that’s not always the case. It can also be sensitive and reactive, so it’s important to move slowly and gently.

It’s also good to consider that there are alternate approaches to trigger point therapy, such as dermoneuromodulation, that may prove more effective if ischemic compression isn’t producing the desired or longer-lasting outcome.

How to find the best trigger point therapy near you?

Despite the lack of clear evidence about the existence of trigger points, trigger point therapy may still provide pain relief for many people because it’s a form of physical touch.

Like most types of massage like sports massage, trigger point therapy doesn’t need to be painful. If your massage therapist insists on such painful treatments, find another therapist.

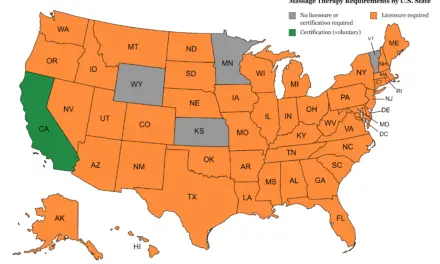

Your therapist should be evidence-informed and licensed or certified. This means that they should be practicing based on the best evidence available so you can be well-informed and not receive treatments that can be harmful.

Some countries have a directory that lists who is a qualified massage therapist near you. For example, in the U.S., there is the American Massage Therapy Association, and in Canada, there are the Registered Massage Therapists Association of British Columbia and The Registered Massage Therapists’ Association of Ontario.

If you know the therapists’ name or their identification number, you can see the status they are in, such as whether their certification or license is active, suspended, revoked, or otherwise. The California Massage Therapy Council has one such feature.

While the debate about the nature of trigger points and myofascial pain continues, rest assured that it doesn’t necessarily negate the benefits of trigger point therapy and other types of massage.

Existing pain theories can still help guide how massage therapists do their work and communicate with you.

Remember that there’s a difference between the hands-on touch of trigger point therapy and the narrative behind how it works. If you find pain relief in trigger point therapy from a great massage therapist, then that’s good news!

But if you’re curious and want to dig deeper into why it works for you, well, the current body of evidence is steering toward a larger scope of why you feel pain—which was mentioned in the realm of neuroscience, immunology, endocrinology, psychology, and even social sciences.

Given the evidence so far, take trigger point and myofascial pain explanations with caution.

“Trigger points are nowhere near as bad as a lot of common pseudoscience and quackery gets, but they certainly do fall well short of ‘proven’ and well-understood. At worst, they may even be a bad idea—a legitimate misunderstanding, an idea that was reasonable 20 years ago but which now needs to be retired or heavily revised.” ~ Paul Ingraham, The Complete Guide to Trigger Points and Myosfacial Pain