Lower cross syndrome refers to the muscular imbalances of the lower body, including the hips, lower abdominals, hip flexors, and legs. The “cross syndrome” term comes from the “X” that you often see from the side view of a person’s body at the pelvis or shoulder girdle.

Some of these muscles in lower cross syndrome get overactive while others get weakened and lengthened, according to the late Dr. Vladimir Janda who proposed the cross syndrome theories. These imbalances can be caused by being in any position for too long, sometimes from an injury or habitual posture.

This type of posture is often blamed for back pain and hip pain, but should you fix it? Well, let’s see what the scientific evidence says.

Types of lower cross syndromes

There are two types of lower cross syndromes: posterior pelvic tilt and anterior pelvic tilt.

Both of these postures can affect the upper body, including the neck and head, which is why upper cross syndrome tends to be addressed with the lower cross version, according to Janda.

Posterior pelvic tilt

Woman with posterior pelvic tilt, based on the cross syndrome theory by Dr. Vladamir Janda. (Photo by Nick Ng.)

The posterior pelvic tilt is where the pelvis is rotated back, causing a reduction in your lower spine curvature. Sometimes it exaggerates the upper spine curve, making you appear more slouched, kind of like Shaggy from the cartoon “Scooby Doo.”

Anterior pelvic tilt

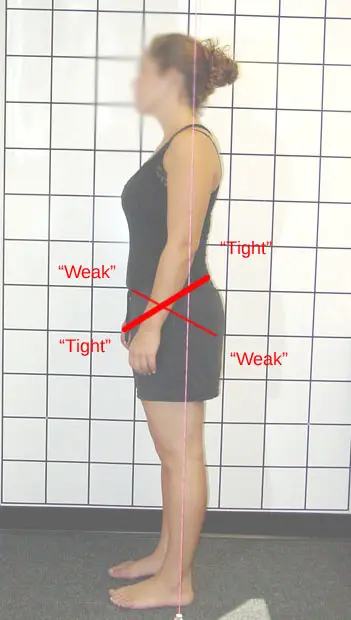

Woman with anterior pelvic tilt, based on the crossed syndrome by Dr. Vladimir Janda. (Photo by Nick Ng.)

The anterior pelvic tilt is where the pelvis is rotated forward, causing your lower back to increase its curvature. This position tilts your buttocks upward, exaggerating its round appearance for some people. Sometimes the pelvic tilt decreases your upper spine curvature, making you appear to have a flatter upper back.

Lower cross syndrome vs. upper cross syndrome

Both types of cross syndromes can influence each other. For example, the anterior pelvic tilt increases your lordosis but it may also increase your upper back curve, which in turn may cause your head and neck to jut forward.

In contrast, the posterior pelvic tilt can cause your spine to appear more like the letter C rather than an S, which can also cause forward head and rounded shoulders.

Of course, not everyone is going to follow this pattern since we each have our own of way of holding up our body.

But don’t take this common idea of crossed syndromes as gospel. For decades, scientific evidence doesn’t find much support in the cause-and-effect relationship between posture and pain, but it may have some influence on movement and function.

Lower cross syndrome symptoms

Lower cross syndrome can cause some muscles to become shortened and overactive or lengthened and inhibited. Basically, if certain muscles are pulled in a certain direction for a long period of time, then the force of tension pulls their “opposing” muscles.

If you have the posterior pelvic tilt, your hip flexors are lengthened and your buttocks may be shortened.

In contrast, if you have the anterior pelvic tilt, your hip flexors and lower back muscles are shortened while your buttocks and abdominal muscles are lengthened and weakened.

These ideas sound reasonable on paper, but scientific evidence shows that it doesn’t apply to everyone.

In one 1990 study of 25 adults, researchers didn’t find any relationship between hip flexor range of motion, pelvic tilts, and lower back curve with abdominal strength.

In another study, there’s a huge variability between women and men in how much gluteal muscle activation they had and the length of their hip flexors while doing kettlebell swings.

In other words, you can’t tell for sure if tight hip flexors actually reduce your butt muscle activation. If lower cross syndrome is true, you’d see a higher number of people with tight hip flexors generating less force in kettlebell swings than those with “normal” hip flexor movement.

However, a 2015 study on female soccer players did find that those with tight hip flexors have lower muscle activity in their glutes. While this may seem to support lower cross syndrome, there wasn’t much difference in their athletic performance or risk of injury.

Should you fix lower cross syndrome?

Posture and biomechanics do influence how we perceive pain, but they don’t influence as much as many people think. Research on the relationship between posture and pain finds that it’s quite poor and inconsistent.

- For example, a 1988 study found no relationship between “tight” hip flexors and back pain among 600 young Swedish soldiers. Researcher and physical therapist Anna-Lisa Hellsing wrote that having tight muscles is not necessarily “good or bad,” rather it’s a byproduct of heavy physical activity, like military training.

“Experience of pain in the tight muscles themselves during the test differed very much between the subjects, but was not systematically recorded,” she wrote. - In 2002, an Iranian study of 600 people failed to find a relationship between those with or without low back pain based on the degree of the anterior pelvic tilt, leg length discrepancy, and the length of the hip flexors and abdominal muscles.

- In 2003, French researchers found that the degree of lordosis among 160 pain-free subjects varies, ranging from less than 35 degrees to more than 45 degrees. And so, posture is not a reliable predictor to determine who has pain or not.

Still not convinced?

A 2014 systematic review of 43 studies found no differences between people with or without low back pain in relation to their low back angle, hip extension, and pelvic tilt in the standing position.

They also found people with low back pain have a reduced sense of proprioception (body awareness in space), tend to move slower, and have greater movement variability back flexion, lateral flexion, and rotation than those with no low back pain.

As you can see, having lower cross syndrome or not isn’t really a good way to determine if that’s a cause of pain or not. Pain is much more complex than just your body’s structure.

“A human being’s posture is not akin to the alignment of an automobile and should never be seen as such. Focus on the thing that matter and help to move us beyond the implausible postural models of care.” ~ Dr. John Synder

Stretches for lower cross syndrome

Whether or not you have a certain pelvic tilt or not, stretching may alleviate some discomfort or pain. It’s no cure-all, but it’s better than doing nothing.

Hip flexor stretch

This stretch lengthens your iliopsoas and their nearby connective tissues. You can do this in a kneeling position or standing up.

- Kneel on the floor on your right knee with your left leg bent in front of you at about 90 degrees.

- Shift your weight toward your left foot and tighten your right buttocks so that you should feel a stretch in your right hip flexors.

- Raise your right arm over your head to increase the stretch.

- Hold this position for about 3 to 4 deep breaths, lower your arm, and shift your weight toward your body’s midline.

- Repeat this exercise on the other side of your body.

3D hip flexor stretch

This stretch is similar to the regular hip flexor stretch, but it adds a lateral and rotational stretch to your hip flexors.

- Start at the same position as the previous exercise.

- Shift your weight toward your left foot and tighten your right buttocks so that you should feel a stretch in your right hip flexors.

- Raise your right arm over your head to increase the stretch. Hold this position for 1 to 2 deep breaths.

- Lean your torso toward your left until you feel a stretch in your right side. Hold this position for 1 to 2 deep breaths.

- Place your left forearm toward the inside of your left knee for balance as you rotate your torso to your right. Maintain the lean and hold the stretch for 1 to 2 deep breaths.

- Repeat the stretch on the other side.

Hip bridges

This exercise strengthens your glutes, ideal for beginners.

- Lie on your back with your feet and knees about as wide as your hips.

- Lift your buttocks off the floor, and hold this position for about two to three deep breaths.

- Lower your buttocks to the floor and repeat this for 8 to 10 reps.

Keep in mind that there’s no “best” exercise for cross syndromes or to reduce low back pain. In fact, a 2016 systematic review of 29 studies with a total of more than 2,400 people found that while core exercises offer some back pain relief, it has “similar outcomes to other forms of exercises.”

A German 2020 systematic review also found similar results. The authors said that low-quality trials seem to “overestimate” the effects of core exercises on low back pain.

Also, it’s more likely that exercise in almost any form can alleviate pain by changing how the central nervous system and the brain process pain.

Since there are no ideal exercises to treat back or hip pain, perhaps the “best” exercise for you would be something that you can do regularly with little or no pain—and you enjoy it, whether you have lower cross syndrome or not.

Further Reading

A native of San Diego for nearly 40 years, Nick Ng is an editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine, an online publication for manual therapists and the public who want to explore the science behind touch, pain, and exercise, and how to apply that in their hands-on practice or daily lives.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a B.A. in Graphic Communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014.

When he is not writing or reading, you would likely find him weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, or exploring new areas to walk and eat around Southern California.