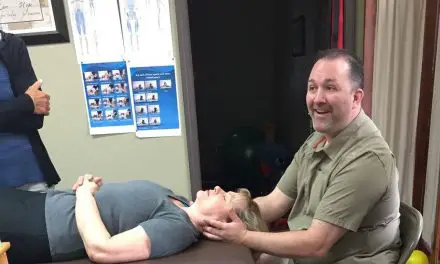

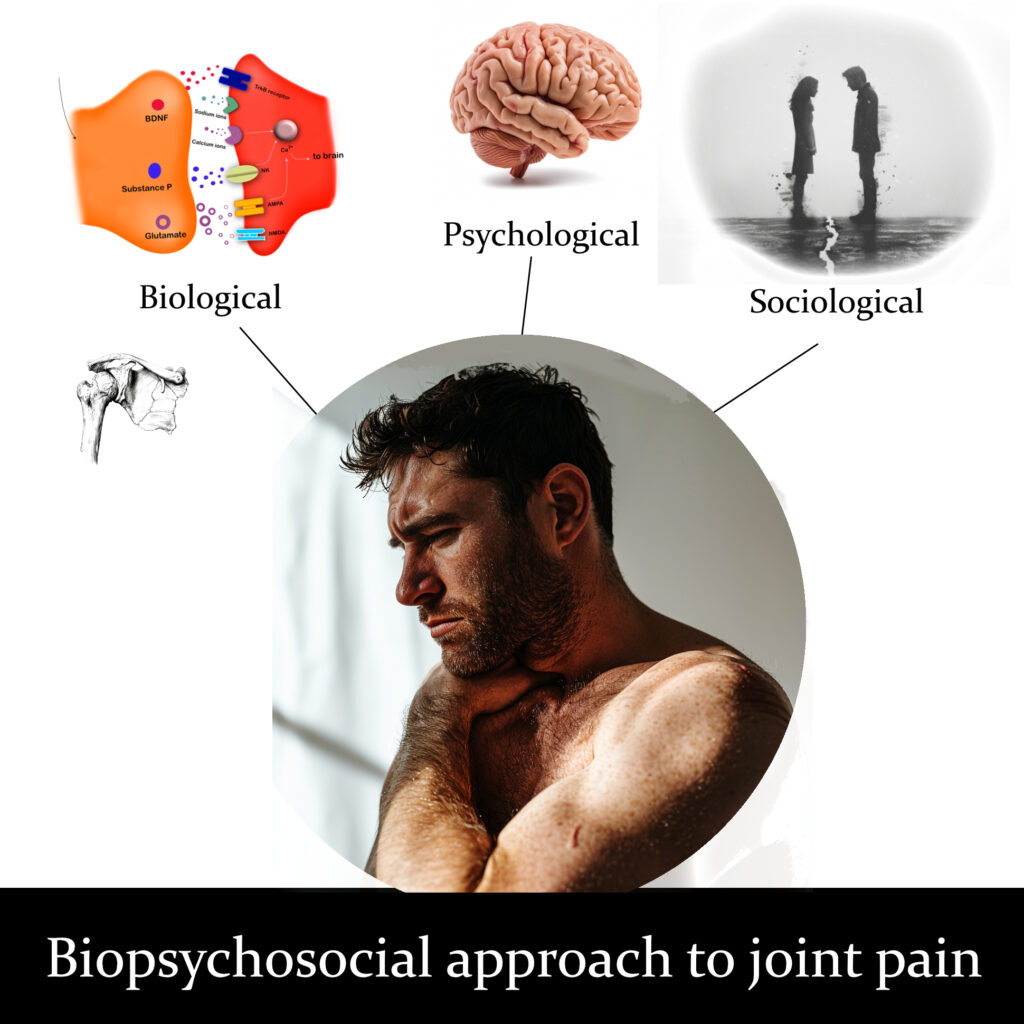

A biopsychosocial approach to joint pain considers the interactions of biological, psychological, and social factors in understanding and addressing someone’s pain experience. Like ingredients in a cake, these factors should be considered together rather than separately.

Biological factors include the physiological aspects, such as tissue damage, inflammation, and structural abnormalities in the joint. These factors may or may not be a cause of pain. Biological factors also include genetics, age, gender, and overall health status, all of which can influence pain perception and response.

Psychological factors encompass emotions, thoughts, beliefs, and coping mechanisms related to pain. Anxiety, depression, fear of movement or re-injury, catastrophizing, and stress can all exacerbate pain or influence how it’s perceived. Conversely, positive emotions, relaxation techniques, and cognitive strategies can help mitigate pain.

Social factors refer to the broader social and environmental influences on pain perception and management. This includes someone’s socioeconomic status, social support networks, cultural beliefs about pain, work and lifestyle demands, access to healthcare, and interactions with healthcare providers. Social support, family dynamics, and societal attitudes toward pain can all impact a person’s joint pain experience.

Applying biopsychosocial approach to joint pain

Practitioners who use the biopsychosocial (BPS) approach would consider all three factors rather than just one factor—mainly the biological factor. While massage and physical therapists are not mental health or social workers, there are ways they can use the BPS approach without breaching their scope of practice.

Diane Jacobs outlines the principles behind DNM at the 2017 San Diego Pain Summit. (Photo: Nick Ng)

For example, if you have chronic knee pain, a massage therapist would assess your knee and other joints in the lower body with palpation and movement testing. They would also review your health intake to see if you have a history of knee pain, physical activity levels, prior surgeries and illnesses.

They would use massage techniques like Swedish or gentle skin stretching to potentially change your pain sensation by affecting the nerves and connective tissues below the skin.

For the psychological and social factors, a massage therapist would use various communication styles to support your care. This includes empathetic listening, asking questions, and developing a strong therapeutic relationship.

The therapist should also recognize the role of culture, emotions, beliefs, stress, lack of social support, and socioeconomic status can significantly influence the treatment outcome, your experience of chronic pain, and your ability to manage it effectively. They should also collaborate with other healthcare professionals and refer out if necessary.

Therefore, therapists should avoid giving nocebic messages to their patients, especially if they’re not supported by scientific evidence, such as your posture is the cause of your knee pain.

“There is no linear pathway or treatment algorithm to follow,” registered massage therapist Eric Purves wrote, highlighting that the BPS approach provides a framework for therapists rather than a rulebook. “There is no correct way of doing things. The biomedical model is easier to comprehend [because] most people understand the basics of biomechanics, and they can rationalize pain or dysfunctions to something tangible like the sensation of a joint or soft tissue not functioning properly or feeling out of alignment.”

Causes of joint pain

Depending on the joint, pain can be caused by external (e.g. contact injury, wounds) or internal factors (e.g. arthritis, sprains, bursitis). Sometimes your lower back might hurt more because of long-term stress due to constant worrying. Thus, a single cause is unlikely to be a source of pain.

(Image by Nick Ng)

Biological factors: Structural changes, such as cartilage degeneration, bone changes, and inflammation, may contribute to joint pain, but these are not always a strong factor for everyone. Comorbidities include obesity and diabetes mellitus.

Psychological factors: Depression and depressive symptoms are strongly associated with higher joint pain levels, such as the knee. Other factors include:

- Anxiety and higher levels of anxiety

- Pain catastrophizing and fear of movement

- Lower self-efficacy in managing symptoms

Social factors influence psychological and biological factors and vice versa. These include:

- Lower socioeconomic status with lower income levels is associated with higher prevalence of knee pain

- Lower levels of social participation and lack of social support, influenced by higher depression levels

- Work demands, ergonomics, and lack of health insurance

Related: Skin sensory receptors: How context affects touch

Go beyond the biological factors

Traditionally, massage and other manual therapists are taught mostly the biological aspects of treating joint pain, such as anatomy, biomechanics, and physiology. But given the biopsychosocial nature of pain, some therapists and researchers have been advocating for a broader approach to patient care for decades.

In 2019, a team of researchers, led by Dr. J.P. Caneiro from Curtin University in Perth, Western Australia, suggested “five actions” to change how therapists manage and treat musculoskeletal pain. They highlighted that such pain “share common biopsychosocial risk profiles for pain and disabilities,” and there are already guidelines for best practice that clinicians should follow, “irrespective of body region.”

1. Spot the red flags

Physiotherapist Jay-Shain Tan at Flex Physio in Perth, Western Australia, said that all healthcare professionals should scan for “red flags.” These are conditions that are potentially dangerous, like cancer, infection, or progressive neurological conditions.

Checking for red flags should be the first step in evaluating joint pain, says physiotherapist Jay -Shian Tan. (Photo: Courtesy of Jay-Shian Tan)

“Those conditions have specific management,” Tan explained. “For instance, if someone has a history of cancer, they have a larger chance of having some cancer that metastasizes in the proximal humerus. That can masquerade as an arthritic shoulder or frozen shoulder. If the person does not have a history of cancer, then you diagnose it as osteoarthritis or frozen shoulder.”

2. Use an updated pain questionnaire

Caneiro et al. suggested that physiotherapists use the Örebro Musculoskeletal Pain Questionnaire, which is used to predict the outcomes of patients during a treatment and the barriers to recovery. It also predicts “yellow flags,” such as long-term disability.

It has 25 questions or statements where 21 of them are rated on a ten-point scale. Higher scores mean higher disability.

3. Let patients be the storyteller

Rather than being the authority of treatment, therapists should use open-ended questions that allow patients and clients to tell their pain experience.

For example, ask “What do you think is the cause of your pain? And why?” or “What do you do when the pain flares up?” or “If you don’t have low back pain right now, what would you do today or tomorrow?”

“There are things like motivational interviewing, acceptance commitment therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy, which—obviously on their own—are not things that we [massage therapists] do,” said Erica DeNeve, who is a registered massage therapist in Edmonton, Alberta. “But there are components of them that absolutely fall within what we do, especially if we’re talking about the biopsychosocial model.”

DeNeve gave an example with acceptance commitment therapy (ACT), which involves patients exploring the relationships among their emotions, thoughts, and behaviors.

“We can use these basic ideas without getting into, ‘Okay, we’re gonna be using this to address your neurosis,’” she said. “Talk to them like, ‘When you have pain coming up, here’s how you can look at that. I talk to patients all the time about this. ‘Okay, here’s how you can reframe those thoughts to help turn down the alarm bells in your nervous system so your brain stops sending out pain signaling.’

“That basic ‘pain science’ talk is what I use with every single patient I see within the first two or three sessions. Here’s how your brain works, here’s why you have this pain experience, and this is what you can do to modify it.”

Rather than being the authority of treatment, massage therapists should use open-ended questions that allow patients and clients to tell their pain experience. (Image: Midjourney)

Sometimes people get a massage not just for the sole purpose of pain relief or the experience, but it’s also a way for them to socialize.

“You might go to your hairdresser to get a haircut, while somebody else might go to a hairdresser and have a good, old chat, and they enjoy that chat because it’s part of the experience of getting a haircut,” Tan said.

Tan also emphasized that the interaction itself between the therapist and the patient is also another vital part of the treatment without stepping over scope of practice.

“Massage therapy, from the way I understand it, is that there are two intents people have, which are ‘I’m going there to get treatment for this problem’ or ‘I’d like to go through the experience of getting a massage because it’s pleasant,’” Tan said. “And they overlap a bit. Within that, you have an interaction. You talk to your client and ask them what they’d like done, and some people are there to describe their problem and have it managed. Some people just like a good, old chat, and they get a lot of benefit from that.”

4. Personalize joint pain relief education

Rather than simply dispensing information, therapists should have patients be part of the learning, such as providing interactive online resources, have them write down their daily experiences about pain, and exercise therapy as a way to help dispel myths about pain and movement.

5. Build independence, not reliance on joint pain treatment

Some patients might need a little boost to help reduce disability and pain to become more independent from treatment. Therapists should teach patients how to keep track of their progress and ways to self-manage their condition.

Caneiro et al. emphasized that therapists should address “unhelpful cognitions,” such as the patients’ negative self-talk, “physical barriers to recovery,” such as building strength and endurance and reducing movement avoidance behaviors, and improving lifestyle factors, such as sleep, regular physical activity, and positive social interactions.

These five actions could be adapted to massage therapists worldwide within their scope of practice.

“It is the responsibility of the massage therapist or physio to suggest a referral,” Tan said. “In a healthcare setting, if someone is having threats of suicide, it’s the responsibility of the physios to contact the patient’s doctor, making sure that they are fully aware of that presence. [The physio] would write a letter and give a phone call to the doctor, making sure that they will follow up on the patient.”

So why aren’t many massage therapists adopting the BPS model?

“The simplest way for me to answer this question is [massage therapists] are not exposed to this information in school,” said registered massage therapist and massage teacher Eric Purves, who applies the BPS model to his continuing education courses.

He added that while there are some valid criticisms about the BPS approach, it is “less wrong” because the framework is about the entire person, not just their body part.

“The curriculum for most massage therapy education is based on history and beliefs, and the adoption of current science or best practices is lacking,” Purves said. “The information that they learn is primarily structural and tissue based.”

And so, your therapist may know a lot about the structure of your hip for SI joint pain or a massage technique, but if they miss out on your narrative and have poor communication skills, probably no amount of stretching or skin rubbing would give them the pain relief you need.

“Patient-centred care will optimise the value of healthcare provided. Shifting funding to support high-value evidence-based care options and educating society will be critical to enable this transition and will likely be cost-effective,” Caneiro et al. wrote. “We believe clinicians are ready to change, but they require the support of health systems and payers.”

For more information about practical applications of the “five actions,” visit: Musculoskeletal Framework for an ebook. Purchase will go 100% back into research funding.

Further reading

What Is the Gate Control Theory of Pain?

Neuromatrix Theory of Pain for Manual Therapists

Descartes to Melzack and Wall: History of Pain Science

A native of San Diego for nearly 40 years, Nick Ng is an editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine, an online publication for manual therapists and the public who want to explore the science behind touch, pain, and exercise, and how to apply that in their hands-on practice or daily lives.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a B.A. in Graphic Communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014.

When he is not writing or reading, you would likely find him weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, or exploring new areas to walk and eat around Southern California.