No matter which type of hip flexor pain you have, they all can be unpleasant and limit your ability to move, even if you’re just getting out of bed. Hip flexor pain can be a burning sensation or a sharp pain near your groin, lower abdominals, somewhere along the front of your waistline, or a combination of these symptoms.

I still remember my first hip flexor pain. It happened after a Brazilian capoeira class in 2005 in San Diego where we did endless ginga drills, which is a basic capoeira move that involves a lot of hip extension.

After what seemed like hundreds of hip extensions and stretching the psoas for an hour, I did not feel any pain in my hip flexors and upper thighs near the inguinal line until the next day. That pain and soreness for nearly a week. I never took getting out of bed for granted again.

Despite foam rolling, stretching, and lots of rest, which provided a very short pain relief, the pain persisted and refused to go away.

Fortunately, the pain gradually fizzled out without needing to take pain medication regularly or to see a doctor or physical therapist. I never took getting out of bed for granted ever again, nor did I take another capoeira class (but I still enjoy watching it and listening to the music).

Hip flexor pain is an umbrella term that covers several types of anterior hip pain. These include iliopsoas syndrome, groin pain, hip tendonitis, iliopsoas bursitis, and hip flexor strain.

Not everyone may recover like I did, but what should we know about hip flexor pain and whether the treatments for it are effective or not? And should I have gotten a massage? Can massage help?

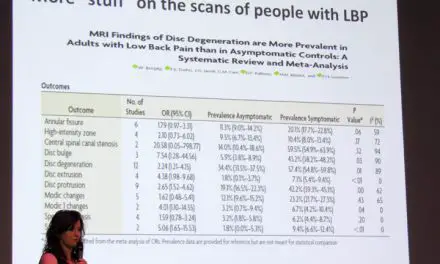

Anatomy and biomechanics of the hip flexors

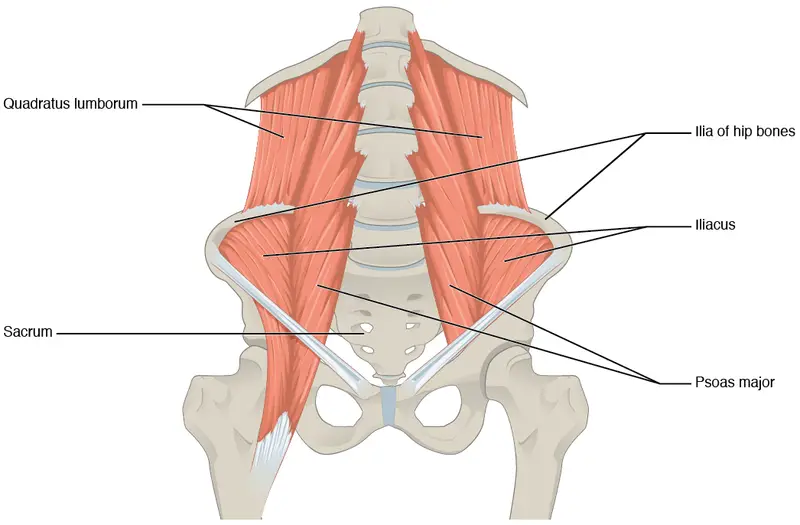

The iliopsoas consists of three muscles that allow you to flex and externally rotate your hip: iliacus, psoas major, and psoas minor. Getting in and out of your car or getting off your bicycle would involve both of these movements. The muscles also help you laterally flex your torso and bend your torso at your hip, like when you bow or deadlift.

The iliacus is a fan-shaped muscle that extends from the iliac fossa of the pelvis and inserts in the lesser trochanter of the femur.

Some of the iliacus’s muscle fibers stem from the anterior sacroiliac and iliolumbar ligaments, which connect the pelvis and lower spine. The iliopsoas bursa separates the iliopsoas tendon from the hip joint, allowing the iliopsoas to move smoothly.

Image: OpenStax College

Located behind the abdominal wall, the psoas major originates from the transverse processes of the T12 to L5 of the lower thoracic spine and the first four vertebrae of the lumbar spine.

Like the iliacus, the psoas major inserts into the lesser trochanter, merging with the iliacus behind the inguinal ligament. The lower part of the iliopsoas forms a part of the femoral triangle, which makes the upper third of the thigh.

The psoas minor sometimes gets overlooked because it is smaller than the other two hip flexors, and it provides limited support for movement. It originates from the lateral sides of T12 and L1 and inserts into the iliopublic eminince and pecten pubis of the pubic bone.

Some clinicians don’t consider the psoa minor to be part of the iliopsoas because not everyone is born with this muscle. One study of 44 cadavers found that 91% of young Black men do not have a psoas minor compared to 13% of young white men.

One Indian study in 2010 found that 70% of the 30 cadavers do not have a psoas minor.

These muscles are surrounded by the iliac fascia that separates the inguinal ligament and the pelvis into two sections: the lateral side that consists of the iliacus, psoas major, and femoral nerve, and the medial side that allow the femoral blood vessels to travel through.

Nerves of the iliopsoas sprout from the lumbar plexus and branch to various hip muscles. The femoral nerve (L2-L4) connects to the iliacus while the anterior rami of the spinal nerves (L1-L3) connects to the psoas major.

Can you massage the hip flexors?

Because the hip flexors lie so deep behind the abdominal wall—not to mention beyond layers of skin, connective tissues, internal organs, fat tissues, outer ab muscles—can anyone really massage the psoas?

Some massage therapists believe they can target the psoas muscles to massage. However, basic anatomy shows that it’s not very likely for most people. Therapists would have to “go through” layers of tissues and organs to reach the psoas major.

Full video here.

“We might be able to provide some relief to patients with techniques that involve the application of pressure to these areas, but not because we are ‘frictioning’ these deep structures,” Jason Erickson said in a Facebook forum, who is a massage instructor in Eagan, Minnesota.

Rachel Ah Kit, who is a remedial massage therapist and clinic director at Bodyworks Massage Therapy in Christchurch, New Zealand, said that therapists must include psychosocial factors, such as stress, work, sleep, and family problems as part of evaluating patients’ history, not just muscles and joints. The history should also include potential physical injury that contributes to the hip flexor pain and down the front of the thigh.

“Clients with anterior hip pain, who say they have issues with iliopsoas, have often self-diagnosed with Dr. Google or they have been told that’s the problem by a well-meaning friend, or even a physiotherapist,” Ah Kit said. “It’s not a muscle the general public are usually aware of.”

Pain following a fall or impact involving excessive hip rotation, with reports of pain after long periods of sitting, standing or walking, should be assessed for a labral tear, which may or may not be associated with femoroacetabular impingement (FAI).

“Therapists can make a quick hip assessment with a FADDIR test (Flexion, ADDuction, Internal Rotation), with the client in supine with the hip and knee passively flexed to 90 degrees, and then adducting and rotating the hip medially,” Ah Kit explained.

“Any sharp hip or groin pain, clicking or guarding on medial rotation may indicate a labral tear, FAI, or ‘snapping hip’ (where the iliopsoas tendon snaps over the pelvic bone) and clients should be referred out for a diagnosis, imaging, and/or rehab management.”

Such tests without a diagnosis are within the scope of practice of massage therapists in New Zealand, but therapists should refer to a physiotherapist or physician if clients report hip pain. Massage therapists must check their local and national laws to see if such manual testing is within their scope of practice.

“Regardless of outcome, the client can still be treated conservatively with massage therapy,” Ah Kit said.

Jamie Johnston, who is a registered massage therapist at The Athlete Centre in Victoria, British Columbia, used to think that he could dig his fingers into a patient’s abdominal region and “palpate and treat” the psoas muscle.

“We can’t actually press deep enough where we are making direct contact with muscles, even when we put a person in the right position and resist hip flexion,” he said. “We can’t effectively push through organs and other tissues that sit on top of the psoas to be able to treat and palpate it effectively.”

Johnston said that many manual therapists hold incorrect ideas about massaging the iliopsoas.

“They blame the muscle for things like postural problems, leg length discrepancies, and even menstrual cramps,” he said. “However, with what we know about modern research around musculoskeletal injuries, much of that is not only false, it is also harmful when it is communicated to a patient.”

He mentioned a 2010 review that suggested reassurance, education, exercise, and (some) manual therapy when treating patients with low back pain and hip pain.

“It should be no different when treating someone with anterior hip or psoas pain,” Johnston said.

Providing reassurance to the patient and showing them they are not broken or have some other “abnormality” because of their psoas (like “tight” hip flexors) is one way to help reduce their pain.

“Educating them about where the psoas is, how it works, and why it isn’t doing all the things these other blogs are talking about is also a crucial aspect of helping someone,” Johnston said.

In terms of exercise, simple isometrics for hip flexion can help reduce pain, Johnston suggested. However, “building resilience” is what exercise therapy can also do, which shows patients how capable and strong they are.

“Also doing some movement on the opposite side of the body, like glute bridges, can help with not just pain reduction but with movement in general,” Johnston said.

How do you massage your hip flexors?

Since the hip flexors lie deep in the abdominal cavity, is there still a way to treat hip flexor pain with massage?

Rather than doing deep tissue massage and other types of massage that promotes aggressive force on the tissues, Ah Kit suggests a “more pleasant and less invasive treatment”—an approach based on dermoneuromodulation (DNM) that addresses the nervous system and skin.

Photo: A therapist might use Dycem to help stretch the skin to change how you feel pain. Photo: Walt Fritz.

“It is possible that pain in the area may be also related to restriction of the femoral nerve where it emerges medially to the ASIS and below the inguinal ligament,” Ah Kit said. “Using skin stretch techniques described by Diane Jacobs in her book, the area superficial to the iliopsoas attachment can be treated before attempting any deeper work.”

Ah Kit suggested that treating the iliopsoas is usually done with the patient lying on their back and their knees and hips slightly flexed over a bolster or large pillow.

“The belly of the iliopsoas cannot be easily accessed, despite what some therapists may believe,” she said. “Deep work superior and medial to the ASIS can be extremely uncomfortable for the client because there is pressure on the ascending or descending colon.

“The femoral attachment can be more easily accessed at the lesser trochanter, with the hip and knee flexed and abducted. Therapists should still work with caution here as it’s located within the ‘femoral triangle,’ bounded by the inguinal ligament, sartorius, and adductor longus muscles and contains the femoral artery, femoral vein, and femoral nerve that therapists should always be aware of and work away from the femoral pulse.”

“The belly of the iliopsoas cannot be easily accessed, despite what some therapists may believe,” Rachel Ah Kit, RMT, said. “Deep work superior and medial to the ASIS can be extremely uncomfortable.” Photo courtesy of Rachel Ah Kit.

But overall, when you’re getting a massage, the biggest influence of pain relief comes from the skin and the nervous system, Johnston pointed out.

“What we can do is touch the general area nicely to influence the nervous system to bring about change and help their pain,” he said. “Doing this in combination with reassurance, education, and exercise will bring about the greatest benefit for the person on the table in front of you.”

Causes and risk factors of hip flexor pain?

Sometimes it’s difficult to find a specific cause of a type of hip flexor pain. You might be driving and whistling to work one day, and when you get out of your car, you feel a sharp pain near your groin and you have no idea why that happened.

But pain always comes from multiple factors, so it’s important to consider that when you talk to your doctor, physiotherapist, or massage therapist.

Some of these factors include:

Hip flexor strain

A hip flexor strain is a tear in the muscle fibers, and it is categorized into three primary grades.

Grade I: minor tears in the muscle fibers; hip flexors still have some range of motion and function. You may be able to continue a physical activity or sport immediately after the injury.

Grade II: There’s greater tear in a number of muscle fibers “without complete muscle rupture.” Range of motion is decreased by 10 to 25 degrees, and you can not continue the sport or physical activity.

Grade III: This is a complete muscle rupture where you are in severe pain with more than a 25% loss of range of motion.

This grading system has been around since 1966, and many have attempted to refine the definition and diagnosis. While much of the research does not pertain to hip flexors, clinicians should be able to extrapolate this information when treating hip flexor pain.

Hip flexor tendinitis

Tendinitis is the inflammation of a tendon often caused by the friction between the tendon and another organ, such as a muscle, a bursa, or another tendon. In some cases, an injury could also cause tendinitis.

Thus, it’s likely that the tendons of the psoas major can get inflamed from overuse or other causes. Compared to other types of tendinitis, like the knee and the shoulder, there’s not much research that examines the effectiveness of treatments and the nature of hip flexor tendinitis.

One hypothesis is that hip arthroscopy surgery may increase the risk of getting hip flexor tendinitis. However, a few studies do not support this idea.

One study by Adid et al. examined medical records of 252 qualified patients who had undergone hip arthroscopy surgery who were tested for tendinitis in their hip flexors and had regular follow-ups over five years post-op.

Only 60 patients (24%) showed one symptom relating to hip flexor tendinitis in the iliopsoas. However, the study didn’t specify if any of these patients had pain or not.

They concluded that iliopsoas tendinitis “is an under-diagnosed, under-reported complication after hip arthroscopy that can restrict the post-operative rehabilitation course if not addressed properly.”

Another study from Shanghai, China, compared 133 patients with total hip arthroplasties for hip dysplasia with 126 patients with the same surgery without hip dysplasia.

The researchers found no differences in the number of incidences between both groups, but the artificial femoral head may irritate the iliopsoas, which may increase the risk of getting tendinitis.

Snapping psoas and iliopsoas bursitis

You may have heard a dull click or popping sound in your hip when you walk or raise your leg up when you are lying on your back. Sometimes it can be painful and limit your ability to flex your hip.

The snapping psoas—sometimes called internal hip snapping or snapping hip syndrome—was once thought to be caused by the snapping motion of the iliopsoas tendon over the iliopectineal eminence of the pelvis when you flex your hip.

However, studies in the last 50 years proposed that there may be multiple causes of hip snapping, such as the snapping of the iliopsoas tendon over the less trochanter or the femoral head of the femur and the “sudden flipping” of the psoas tendon over the iliacus.

Sometimes the regular snapping may cause symptomatic hip bursitis where the iliopsoas bursa may likely get inflamed.

Although some research finds a lack of bursa abnormalities among patients who undergo surgery for painful snapping psoas, some researchers coined the term “iliopsoas syndrome” to include a variety of symptoms and causes.

Tight hip flexors: Is that a sign of dysfunction?

There’s little research that examines whether shortened or “tight” hip flexors cause or are associated with low back pain, yet many manual therapists and personal trainers seem to take this as a fact.

Google “tight hip flexors” and you would likely see that the first two pages consist mostly of citing hip flexors as a “cause” for low back pain, hip pain, and other types of pain.

While research in this specific topic is lacking, some evidence indicates a weak or no association between tight hip flexors and low back pain.

One major research on this was published in the Upsala Journal of Medical Sciences in 1988 where about 600 young men, who were enlisted in Swedish military service, were examined at the beginning and during the service over a four-year period.

Researcher Ann-Lisa Hellsing concluded that “Tight hamstring or psoas muscles could not be shown to correlate to current back pain or to the incidence of back pain during the follow-up period.”

She mentioned that having tight muscles could stem from other factors, such as genetics, heavy strength training, long-term pain, and poor movement patterns. The study also shows a lack of back pain relief from stretching tight psoas and hamstrings.

While there has been very little research since Hellsing’s work that examines this specific relationship, indirect evidence from postural studies also support her findings.

For example, a large Iranian study in 2002, which compared 600 men and women in their twenties to fifties with or without low back pain, found no association between body structure and posture (e.g. leg length discrepancy, lordotic curve, iliopsoas length) with low back pain.

A 2014 systematic review and meta-analysis of 43 studies that compared movement and lordosis angle found no differences between people with low back pain and those without.

Because lordosis is often associated with the anterior pelvic tilt—where the iliopsoas are “shortened”—this does not affirm that shortened or tight hip flexors are a cause or strong association with low back pain.

Hip flexor pain treatments

Aside from pain medications, conservative treatments, such as exercise and manual therapy, may reduce hip flexor pain. Because there are different causes of hip flexor pain, no single treatment is a cure-all. Always consult your physician or another healthcare provider if your hip flexor pain is chronic or severe, impeding your daily activities and sleep.

Hip flexor stretching

Stretching may provide some temporary relief of hip flexor pain, like most stretches for other body parts, even though research showed that static stretching for low back pain and neck pain showed mixed results. It’s likely that different people and populations have different responses to stretching. Thus, there is no one-size-fits-all answer to whether stretching will work for you or not.

Standing hip flexor stretch

Stand with your right foot in front of you and your left behind you. Turn your left foot inward slightly so that it points toward your right heel. With your hands on the sides of your hips, shift your weight forward and contract your left buttock slightly so that you should feel a stretch in your left hip flexors and thigh.

Raise your left arm over your head to increase the stretch. Hold the stretch for 20 to 30 seconds. Repeat the stretch on your opposite side.

3D hip flexor stretch

The “3D” implies the three planes of motion that you can use for the hip flexor stretch.

From the previous stretch with your left arm extended over your head, lean your torso to your right until you feel a stretch on your sides. Hold this position for 20 to 30 seconds.

While maintaining the lean, turn your torso to your left as much as you can or at least you feel a “twisting” stretch in your hip flexors. Hold this position for 20 to 30 seconds. Repeat the stretch on the other side.

You can also do this stretch from a kneeling position.

Hip flexor strength exercises

There’s limited scientific evidence that examines whether strength exercise can help reduce or manage hip flexor pain. One randomized-controlled trial with 33 healthy, female athletes finds that strength training of the hip flexors may be “promising for future prevention and treatment of acute and longstanding hip-flexor injuries.”

Given that exercise, in general, has some analgesic effects, perhaps almost any type of strength training exercise can help alleviate the symptoms—similar to low back pain studies where no type of exercise is superior to another for reducing pain.

Supine knee ups with band

For beginners, you can start by lying on the floor on your back with your legs together. Then bring your knees toward your chest and straighten your legs back to the starting position.

When this gets easier, progress to raising one or both legs straight to the air. Bring your knee as close to your body as possible and return to the starting position.

For another level up, try the exercise like in this video below. All movements are done in a controlled manner, so no swinging.

Standing hip flexion with band

Knee tucks

Running high knees

For a more advanced level, this exercise can help improve strength and power production and motor control of your hip flexors, legs, and other hip muscles.

Surgery

There are different types of surgeries for different hip flexor pain, which is beyond the scope of this article.

However, it’s worth noting that some studies find improvements in surgical techniques that reduce “complications” among patients post-surgery.

A 2016 review on iliopsoas pathology finds that open surgeries to lengthen or release the psoas major that is rubbing against the iliopsoas bursa have a rate of 21% of complications versus 2.3% with arthroscopic surgery.

Recurrence of the snapping hip syndrome among those cases with open surgeries has a rate of 23% compared with 0% of arthroscopic surgery cases.

Despite the success rate of arthroscopic surgeries for this type of hip flexor pain, many studies on surgeries for low back pain, knee pain, and shoulder pain have shown that they are not that much different than sham surgeries. Whether or not this would apply to hip flexor pain is currently unknown.

“Pain is a biopsychosocial experience. So from a biological perspective, considering the joints, muscles, the nervous system, motor control and coordination, as well as cardiovascular and lymphatic systems,” said physiotherapist Antony Lo, who practices at The Physio Detective at Oatley, New South Wales, Australia. “These are important, but that’s not the whole picture.”

When treating patients, Lo emphasizes the patients’ beliefs, attitudes, meaning, and stories—or “BAMS,” as he calls it. These underlying issues can also contribute to the pain experience, even though they seem to be unrelated health issues.

“And that’s just for the hip region itself,” Lo said. “There are also referred pain sources and other issues which can cause anterior hip pain. It is so much easier to provide a simple test and answer with a solution, but the reality is far from the truth.”

“If I honestly think it is the iliopsoas muscle that is causing the problem, I will try to prove it is everything else first. Only then will I settle on the iliopsoas to be the primary contributing factor.” Photo: Antony Lo.

Lo cautioned that tests don’t always tell the therapist or the patient about the cause of the hip flexor pain. He gave the Thomas Test as an example.

“The Thomas Test is considered valid for testing hip extension, but it doesn’t tell you why,” he said.

In a 2016 paper by Vigotsky et al., the researchers found that the Thomas Test is unreliable to measure hip extension unless the therapists account for the position of the lumbar spine and pelvis.

Even so, using pelvic landmarks is not reliable because different people have variations of bony landmark positions. And so, the textbook standard for finding “neutral pelvis” is unreliable and therapists may likely make a wrong diagnosis and treatment plan.

Because hip flexor pain is complicated like most types of joint pain—and it’s difficult to prove— Lo suggested that manual therapists should approach clinical interactions with patients with a scientific mindset. This would include using inductive reasoning, a way of thinking about how likely something would happen. There could be other reasons that cause hip flexor pain that clinicians might overlook.

“It is far too easy to find information that confirms what we think,” Lo said. “Therefore, if I honestly think it is the iliopsoas muscle that is causing the problem, I will try to prove it is everything else first. Only then will I settle on the iliopsoas to be the primary contributing factor.”

Perhaps this is one reason why I did not seek help when I had hip flexor pain more than 15 years ago. The last thing I wanted was to pay and spend time on a treatment that may or may not work. Since hip flexor pain research is lacking, the best approach so far is to take the pain research from other areas and apply it to hip flexors.

“If we could all approach our clinical interactions with this scientific mindset, then we are much more likely to have empowered and motivated patients who can make better decisions based on good quality information,” Lo said.

Nick Ng is the editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine and the managing editor for My Neighborhood News Network.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a bachelor’s in graphic communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014. In 2021, he earned an associate degree in journalism at Palomar College.

When he gets a chance, he enjoys weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, and exploring new areas in the Puget Sound area in Washington state.