The 2010s saw a gradual shift in interest in massage and physical therapy education in applying research to practice, particularly in the area of pain.

Many research during the 2010s challenged traditional ideas on how pain works and what it is. Since most of these research are built upon previous research in the previous decades, the biopsychosocial framework of pain and health is not new. However, for many therapists, this is quite new to them. Because of the increased usage of social media since the early 2010s, information about pain, exercise, and other topics spread to individual practitioners worldwide.

Numerous social media pages that are dedicated to the science of pain and exercise pop up in the past ten years, including Physio Meets Science (Germany), Arbilla Exercise Physiology (Australia), Pain Decoded (Chile), and Movement Pain PT (Indonesia). While the number of therapists who are updated in their knowledge about pain is still quite small, this shift may hit critical mass in the 2020s if the trend continues.

Top 10 Pain Research That Challenged Dogma in the 2010s

10. Exercise for the Prevention of Low Back Pain: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Controlled Trials.

No matter what a therapist is trying to “do” to your body, exercise currently still is the best choice of preventing and managing low back pain. The researchers found that strengthening spinal muscles combined with stretching and aerobics two to three times a week could reduce the risk of getting low back pain by at least 30 percent. However, there is not much difference in outcomes of pain intensity and disability in studies that included exercise only versus exercise with pain education.

Although there are some limitations to this study, such as poor exercise adherence during a long-term follow-up, potential publication bias, and poor cluster analysis, the researchers stated that the benefits of exercise for low back pain “seems robust.” Future studies should focus on how to promote strength training programs to clinical practice.

9. Do schoolbags cause back pain in children and adolescents? A systematic review.

Despite what your parents may have told you about carrying heavy backpacks, numerous research do not find heavy backpacks or schoolbags to be a reliable predictor for back pain among children and teenagers. This 2018 systematic review found that “schoolbag use does not appear to be an important risk factor for back pain in children and adolescents.” However, because of the low-quality methodologies in many of the five longitudinal studies and 60 cross-sectional studies that were included in the review, the researchers said that their findings “should be interpreted with caution.”

In the bigger picture, more research has found more reliable predictors that increases the risk of low back pain among teens and children, and they are not biomechanics.

8. Disabling chronic low back pain as an iatrogenic disorder: a qualitative study in Aboriginal Australians

Romanticism of indigenous cultures has led to some people in the West believe that people in these cultures do not have low back pain. However, several studies in Australia and South America have dispelled that myth.

One of these studies, led by Dr. Ivan Lin from the University of Western Australia, interviewed 32 Indigenous Australians in three different communities in the outback. Like many other cultures, Indigenous Australians have low back pain, but they do not talk much about it nor do they often seek medical attention. Lin found that some of the men do not talk about back pain in the workplace because of racism. “Issues of racism, in these cases as they related to the working environment, are a further consideration for treatment, follow-up, and recovery,” Lin wrote.

7. Constructing and Deconstructing the Gate Control Theory of Pain

While the gate control theory of pain has transformed how clinicians and neuroscientists understand pain in the mid-1960s, it does not explain entirely about why and how we sense and perceive pain. Dr. Lorne Mendell of Stony Brook University, New York, reviewed the history behind how the gate control theory of pain started and what the authors—Dr. Ronald Melzack and Dr. Patrick Wall—had actually written, rather than just the highlights that many subsequent authors had cited about the famous pain paper.

“The simple diagram of the gate circuit in the Science paper is what is remembered by most, but this was just a small part of discussions in that paper. It forced a re-evaluation of pain mechanisms and it is the outcome of this re-evaluation rather than the simple mechanistic diagram that represents the major significance of the Gate Control Theory,” Mendell wrote.

In the late 1980s, Melzack expanded the gate control theory to the neuromatrix theory of pain, which include affective, cognitive, genetics, and environmental factors as part of the overall pain experience.

Further reading: The golden anniversary of Melzack and Wall’s gate control theory of pain: Celebrating 50 years of pain research and management

6. Massage for Low Back Pain

A downer for many massage therapists when this came out in 2015, the authors of the Cochrane Review stated that they have “very little confidence that massage is an effective treatment” for low back pain. This conclusion is based on 25 randomized-controlled trials in which most of them have low- quality methodologies and have small sample sizes.

This is quite different from a 2008 Cochrane Review that said, “Massage might be beneficial for patients with subacute and chronic non-specific low-back pain.”

The change is due to an inclusion of 12 studies on top of the 13 studies in the 2008 review, which could push the evidence needle to an opposing conclusion.

“When an earlier review is based on a small to medium number of studies, the conclusions will necessarily be tentative, and only a few new studies with divergent results can have a big effect on the bigger picture,” Dr. Christopher A. Moyer said in an interview that discusses the Cochrane Review. “In their earlier review of massage therapy for low back pain, they reviewed 13 studies that, taken together, led them to conclude that ‘massage might be beneficial for patients with subacute and chronic non-specific low-back pain, especially when combined with exercises and education.’ That’s a fairly optimistic conclusion.”

This review may change how massage therapists reframe their thinking about the work they do, even if it does not change a lot of their hands-on work. “This needs to be reflected accurately in conversations with clients/patients and with other professionals,” Moyer said. “If a client/patient asks whether massage therapy is likely to help with low back pain, a fair and accurate answer should indicate that the latest research does not strongly support this, though it is also unlikely to have any adverse effects and it may be helpful under the right conditions.”

5. Diagnostic Imaging for Low Back Pain: Advice for High-Value Health Care From the American College of Physicians

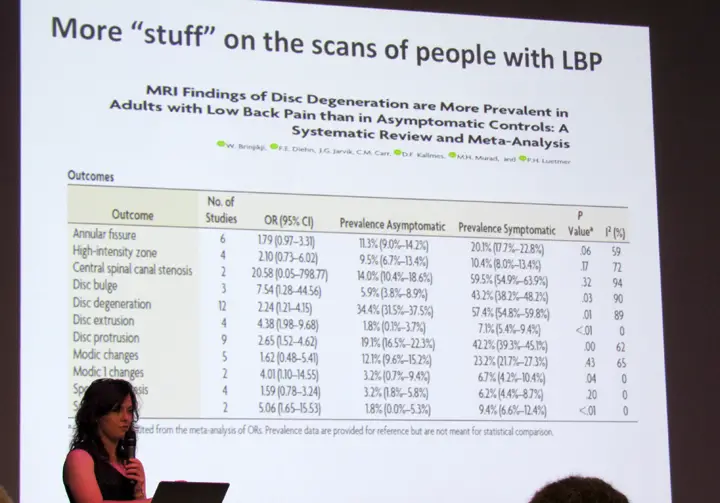

In 2011, a huge paper published in Annals of Internal Medicine cautioned healthcare professionals about overusing imaging for patients with low back pain. Outside of disease, infection, and physical trauma, imaging (e.g. MRIs, X-rays) is not a reliable method to find the cause of low back pain.

The authors concluded: “The ACP has found strong evidence that routine imaging for low back pain by using radiography or advanced imaging methods is not associated with a clinically meaningful effect on patient outcomes. Unnecessary imaging exposes patients to preventable harms, may lead to additional unnecessary interventions, and results in unnecessary costs. Diagnostic imaging studies should be performed only in selected, higher-risk patients who have severe or progressive neurologic deficits or are suspected of having a serious or specific underlying condition.”

They emphasized patient education as an alternative to imaging for low back pain since most spine “abnormalities” are asymptomatic.

4. Systematic Literature Review of Imaging Features of Spinal Degeneration in Asymptomatic Populations

Disc herniation and related characteristics are likely to be a sign of normal aging rather than a disease or disorder that needs to be “fixed.” A 2015 study examined more than 3,000 asymptomatic subjects from ages 20 to 80 and found that the prevalence of disc hernia, disc degeneration, and other vertebrae issues is higher among older adults than young adults. For example, 96 percent of 80-year-olds have disc degeneration compared to 37 percent of 20-year-olds.

“These findings suggest that many imaging-based degenerative features may be part of normal aging and unassociated with low back pain, especially when incidentally seen. These imaging findings must be interpreted in the context of the patient’s clinical condition,” the researchers concluded.

Further reading: A Disc Bulge Does Not Always Correlate to Back Pain

3. Motor Control Exercise for Chronic Non-Specific Low-Back Pain

The core training craze of the late 1990s continues into the 2010s but with less fanfare. However, the belief that core training is the best way to reduce low back pain was still pretty common among manual therapists and personal trainers. In 2016, a systematic review of 29 studies with more than 2,400 subjects total do not find core training (or motor control exercise) to be superior to other forms of exercise, like walking.

Dr. Bruno Saragiotto from the University of Sydney said in an interview that this study does not mean core training is useless. “If you have a previous training or experience on [motor control exercise], you should use because it seems to be effective just like other exercises, the same if you are trained in another type of exercise (i.e., Pilates), they seem to be equally effective,” he said.

“The open question here is whether there is a subgroup of patients that would respond better to [motor control exercise] than other type of exercises, but we can’t answer this question yet.”

Rather than giving patients a one-paradigm-fits-all approach, clinicians should consider options for patients based on their preference of exercise, ability to perform them, and the cost of an exercise program.

2. A Critical Evaluation of the Trigger Point Phenomenon

One of the most critical papers that interrogates the concept of trigger points, Quinter, Bove, and Cohen dissects various ideas about the nature of these elusive tender and sometimes painful areas, including the underlying pathology, EMG studies, clinical diagnosis based on palpation, and capturing an image of a trigger point. Much of these studies on trigger points do not validate their existence nor do the methodologies (such as palpation) are reliable. However, the authors do not discard the patients’ experience of these tender spots.

They concluded: “We propose that sufficient research has been performed to allow TrP theories to be discarded. The scientific literature shows not only that diagnosis of the pathognomonic feature of MPS (the TrP) is unreliable, but also that treatment directed to the putative TrP elicits a response that is indistinguishable from the placebo effect.”

Rather than pursuing the old trigger point narrative, the authors propose the phenomenon should be examined from a different light, such as the neurobiology of pain and nociception.

1. An Enactive Approach to Pain: Beyond the Biopsychosocial Model

Every generation or so, a good scientific theory may get overturned and replaced with a different model or expanded with more accurate (or less wrong) explanations. The biopsychosocial model of pain may be replaced or expanded with the “5E:” Embodied, Embedded, Enacted, Emotive, and Extended.

Authors Peter Stilwell and Katherine Harman of Dalhousie University explained that the biopsychosocial model is still stuck within its foundation, “resulting in the perpetuation of dualistic and reductionist beliefs” and “continues to draw artificial lines and ignore the person as a dynamic whole….”

The 5E comes from the work of philosopher Shaun Gallagher, who propose the “4E” as a way to understand the human mind. Stilwell and Harman added “emotive” as the fifth E, which describes and includes emotion as part of the pain experience. This enactive approach does not negate the biopsychosocial model; rather, it refutes the dualistic and categorical thinking about pain.

Perhaps the increased usage of social media brought more awareness and interest in research to many manual therapists around the world—more so than the 2000s. It is quite difficult to just pick ten research papers since there are so many that influenced clinical guidelines and practice, from longitudinal studies on low back pain to systematic reviews on taping. If you think there are some research that are worth mentioning, please comment below with the research paper’s title, link, and why you think this is important.

Which research had made a meaningful impact on how you work and think?

A native of San Diego for nearly 40 years, Nick Ng is an editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine, an online publication for manual therapists and the public who want to explore the science behind touch, pain, and exercise, and how to apply that in their hands-on practice or daily lives.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a B.A. in Graphic Communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014.

When he is not writing or reading, you would likely find him weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, or exploring new areas to walk and eat around Southern California.