Many people would agree that pain is unpleasant and disrupts their quality of life, regardless of whether it is acute pain or chronic pain. But pain is a necessary survival mechanism that teaches us to avoid danger and behaviors that increase the risk of personal harm. Without pain, we probably would have a hard time surviving into adulthood because we would not have been able to notice infections, wounds, injuries, and certain diseases.

Most acute pain lasts much shorter, from a few seconds (like touching a hot cast iron skillet) to a few hours or days (e.g. muscle soreness, migraines). Acute pain, by definition, is a type of pain that lasts four weeks or less. Some researchers classify it as lasting between seven to 30 days.

Chronic pain is usually defined as pain that lasts more than three months. This is based on the idea that most tissue damage heals in less than three months, but this is a flawed premise because the body of pain research indicates that tissue damage is not a reliable predictor or indicator of how much pain you have—if there is any at all.

Acute vs chronic pain

To understand acute pain better, perhaps it should be examined alongside with chronic pain, which gets much higher attention. Most research behind the time frame of acute pain is based on post-operative pain. The American Academy of Pain Medicine narrowed the definition down to pain lasting up to seven days and sometimes within 30 days, depending on the mechanism, severity, and cause of pain. Any pain that lasts between 30 to 90 days is called “subacute,” which shares some attributes with both acute and chronic pain.

While acute pain can teach us to avoid danger, redirect our attention to our environment, and change our behaviors, chronic pain seems to have almost no benefit to us. This is similar to how our immune and stress responses can be beneficial in the short run to fight infections or escape from a lion, respectively.

But if either one of those responses is prolonged—long after the infection or the lion is gone—then that may lead to certain diseases and disorders, such as autoimmune diseases and rheumatoid arthritis.

Acute pain is usually specific and obvious in cause. A bee sting, a knife wound, a concussion from boxing, and a stubbed toe are some examples. But not all acute pain is that obvious. Some of us may have noticed a non-painful bruise on our leg or a small (slight itchy) skin bump from a bug bite, and we have no idea what caused it or when it happened.

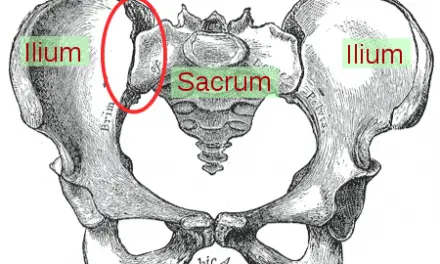

It often goes away on its own or with minimum first-aid care within a week, and we go about our regular business. Chronic pain can be widespread, like fibromyalgia or CRPS, or more localized like the sacroiliac joint or a frozen shoulder. In latter, the intractable pain can last for months or years with little or no obvious cause.

Pathophysiology of acute pain

Research has found that both acute and chronic pain share many similarities in their mechanisms. And regardless of the type of pain, the pain experience still falls within the biopsychosocial model that considers the biological, psychological, and sociological factors.

Dr. Michael Kent, who is an anesthesiologist at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, in Rockville, Maryland, worked with a team of physicians in 2017 to update the classification of acute pain. They found that the current understanding of acute pain “poorly differentiates” between acute and chronic pain because its definition is “often insufficient.”

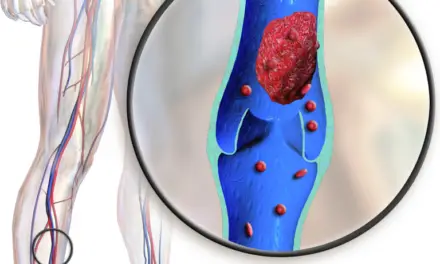

What they mean is that different types of pain, such as nociceptive, muscular, or inflammatory, share many common features between acute and chronic, and it makes diagnosis difficult in many cases. For example, it is thought that peripheral nerve pain is a primary feature of acute pain, but many types of chronic pain also share this feature. Likewise, central sensitization is often thought to be associated with chronic pain, but evidence indicates that this occurs in acute pain, too, such as the insula and anterior cingulate cortex of the brain.

However, central sensitization in chronic pain activates in certain brain regions that do not often show in acute pain (e.g. parts of brain stem nuclei, dorsolateral frontal cortex).

It’s simply “infeasible” to distinguish between acute and chronic pain, Kent et al. concluded.

It is possible that acute and chronic pain can be mostly explained with existing pain theories, such as the neuromatrix theory of pain. This theory, developed by the late Dr. Ronald Melzack in the late 1980s, explains that our pain experience comes from the network of neurons in the brain that “loops” between the outer mass of your brain (cerebral cortex) and the thalamus and the limbic system, which are deeper and toward the middle of your brain.

The network conjures what Melzack calls a “neurosignature,” which makes up the unique experiences that we all have. This is influenced by our biological properties (e.g. genetics, hormones, neural synapses), psychology (e.g. behavior, personality, thoughts, beliefs), and social factors (e.g. family, geography, government, employment).

The neuromatrix theory is an “upgrade” from the revolutionary gate control theory of pain that changed how clinicians and pain researchers think about pain, which changed how pain is treated and was taught in medical school in the 1970s.

Acute pain treatment

Aside from common medications that your physician might prescribe to you, such as opioids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), acute pain treatments can vary, depending on the nature of your pain.

Most of the time, it requires basic first aid treatment or nothing at all. But sometimes the pain can persist for more than a week or a month that might transition to chronic pain.

For musculoskeletal acute pain, treatment may include exercise, sleep, massage therapy, stress management, and medications to manage your pain in the short term. Research has shown that different types of joint pain may respond differently to exercise treatment.

For example, a 2020 systematic review reviewed 24 systematic reviews with a total of nearly 3,000 patients found that no specific types exercises are better than others for treating acute low back pain. Therefore, clinicians should not claim that their favorite exercise modality, such as “core” training or the McKenzie approach, is the “best.”

A better way would be to allow patients with acute low back pain to explore different movements that they can do without or minimal pain or fear. Clinicians should be supportive during their progress and listen to their narratives about their pain and what they believe.

Like chronic pain, there is no one-size-fits-all treatment for acute pain. For clinicians, having treatment options and plan and elbow room to adapt to each patient would be a better approach.

Disclaimer: The purpose of this article to inform, not to substitute your personal medical advice. See your doctor to find out what treatment plan works best for you.

A native of San Diego for nearly 40 years, Nick Ng is an editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine, an online publication for manual therapists and the public who want to explore the science behind touch, pain, and exercise, and how to apply that in their hands-on practice or daily lives.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a B.A. in Graphic Communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014.

When he is not writing or reading, you would likely find him weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, or exploring new areas to walk and eat around Southern California.