While research can inform massage therapists about what they do, how can they tell the difference between good research and bad ones?

Does massage therapy actually lower cortisol level in our body? If you search on Google Scholar or PubMed, you might find numerous studies that say, “Yes!” However, if you dig a little deeper and examine the literature on a broader scale, it actually says, “Not really.”

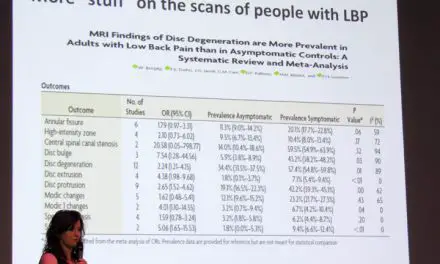

Psychologist Christopher Moyer broke down the conflicting research about massage therapy’s effect on cortisol levels at the Registered Massage Therapists’ Association of British Columbia’s Mental Health Symposium in 2017. On one hand, some research—primarily done at the Touch Research Institute (TRI) in Florida—found that a single dose or multiple doses of massage can reduce cortisol significantly.

But Dr. Moyer’s research team found “very little, if at all.”

Moyer et al. reviewed 19 qualified studies with a total of 704 participants (614 adults). The data points stretched across the chart, meaning that there is a high variability among the subjects.

Dots with long black horizontal lines that cross the vertical dotted line (the mean) tell us how strong or weak the effect of the treatments were.

Massage research is still quite low in quantity and quality compared to physical therapy and nursing, and it still runs into many problems that other healthcare professions face. As Moyer had presented, massage therapists should not take what they read for its face value, and they should critically appraise research within and without our field.

So what should massage therapists consider when they read massage research? The guides shows you six things that you should look for from several scientists.

What should you fact check in massage research?

An editorial published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine (BJSM) suggested why physical therapists need to adopt a strong and honest evidence-based practice to avoid misleading the public and to draw attention to interventions that are effective and efficacious.

The authors gave an example where patients with acute low back pain should get physical therapy first as the first line of defense, but this statement from the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) is not backed up by sound evidence.

In fact, they cited that such endorsements ignored the “high-quality evidence that early physical therapy is more costly and provides no benefit over usual care of [low back pain].” They also emphasized that patients who get physical therapy are more likely to use opioids, imaging, surgery, and injections than those without physical therapy. The quality of evidence, though, was low.

This is where fact-checking my reading the entire article is necessary. Misleading the public can deepen the stereotypes and promote a negative criticism of our profession in their eyes.

Therefore, understanding research and watching out for false claims can initially improve what we market and say to our clients and patients.

So where do we start to disseminate what is good, poor, and everything in between?

“I recently heard a man interviewed on my local public radio station complain about the difficulty of keeping up with what he called the ‘swerves of scientific wisdom’: ‘I spent two tours in Iraq as a gunner,’ he said, ‘and I know how hard it is to hit a moving target. I wish these scientific experts would just hold still.’

“But that’s the thing. Holding still is exactly what science won’t do.”

~ David P. Barash, evolution biologist and psychology professor, Aeon

1. Prior plausibility

If your mom told you that a great white shark had attacked her boat while she went fishing, showed you the damage to the hull, and you know the waters where she fished is home to sharks, then you’d probably believe her.

But if she told you that a two-headed sea serpent had attacked her and showed you the same evidence, you’d probably ask for more evidence and fact check your mom.

This is basically what prior plausibility implies: how valid is a claim based on the existing body of knowledge? In that example, do two-headed sea serpents exist given what we know about marine biology and paleontology?

Our understanding of the natural world and the universe comes from several centuries of observations and experiments that evolved in small increments. Even though these changes can sometimes overturn established facts, new theories are still based on the fundamental principles of physics, chemistry, biology, and other sciences.

Thus, healthcare professionals should not make up an idea out of thin air and establish it as a fact (and sell it!) if it contradicts the existing body of knowledge. To do so, we would need an immense amount of data to overturn the existing knowledge.

“The amount of evidence necessary to add one small bit of incremental understanding about a phenomenon is much less (and should be less) than the amount of evidence necessary to entirely overturn a well-established theory,” neurologist Steven Novella had explained on his blog when someone criticized the application of prior plausibility in medicine.

2. Methodology: most important part to fact check

Photo: Max Pexels https://www.maxpixel.net/Acupuncture-Treatment-Physical-Therapy-Therapy-1698832

We tend to pay more attention to the conclusions and headlines of the research paper than how it’s done (methodology) and what the researchers found (results). That’s probably because they’re quite dry and foreign to us when we see those numbers, symbols, and abbreviations.

For example: One-way ANOVA: F(1, 20) = 8.496, p<.0035, ηp2 = . 198). Unless you’re a statistician or a scientist, who’s gonna understand that right away?

If we don’t have a strong background of statistics and methods, our eyes glaze over the text while our brain enters a screensaver mode. This can make us overlook important data that could tell us more about how well or how poor the experiment was done.

“The Introduction and Discussion sections are subjective and could be biased to make the study look favorable and important,” Dr. Anoop Balachandran said, who is the Assistant Professor of Exercise Science at Queens College at the City University of New York in New York City. “Remember that the methods and the results section are the only objective sections of a study.”

He suggests that clinicians follow the “PICO” of the study, which stands for population, intervention, control, and outcomes. Balachandran describes PICO as follows:

“P stands for population.

“It tells us what the population is used in the study. For example, it could be people with chronic pain, acute pain or hip or knee osteoarthritis, older adults, males and so forth.

“Research is very population-specific, and an intervention that works for acute pain or in older adults may not work well in younger or who have chronic pain.

“I stands for intervention.

“It is also important to understand the specifics of the intervention. For example, if an exercise intervention, specifics—such as how many days/week, intensity or dosage, duration, and so forth—should be noted. The specifics of an intervention can make a big difference.

“For example, a 10-week intervention could have different outcomes compared to a similar intervention but with a longer duration of one year.

“C means control or comparator group.

“This tells us what researchers are comparing the intervention against. People always talk about the intervention but ignore the control group.

“For example, a new exercise intervention could look spectacular if my control group is just a sedentary control, but it will look mediocre if I compare it to group that is given a standard exercise protocol.

“O stands for outcomes.

“What are their main outcomes? The primary outcome for manual therapists’ studies are pain or/and physical function. What people care about is if they feel better or move better.

“For example, improving ROM (range of motion) is usually an outcome, but this outcome has no meaning in a person’s life whatsoever. This outcome only becomes meaningful if the improved [range of motion] helps with tasks that were previously impossible, like washing hair or wearing a jacket. So outcomes do matter.

“Once you have identified the PICO, you have managed to understand the bulk of the study in a very short time.”

Regardless of which profession the research is focused on, methodology applies to all randomized controlled trials (RCTs), Balachandran explained. Some of these factors are:

1. Did the participants have an equal chance of falling in either of the groups ( were they randomized)?

2. Could the participant or investigator have predicted which groups they will fall into (concealed allocation)?

3. Were the participants and investigator blind to the treatment (double-blind)?

4. Did they include all the participants in their final analysis (intention to treat)?

“In my opinion, the most important methodological concern for manual therapy studies is blinding,” Balachandran said. “Did the participants knew if they were getting the real or the sham treatment? Ideally, we want the sham treatment to look and feel exactly the same as the intervention minus the part that is supposedly giving the benefits of the intervention.

One example he gave is studies on acupuncture and its effect on certain pain relief. When such trials compare actual acupuncture versus fake acupuncture, where the needle retracts into a sheathe after the needle contacts the skin, both types show almost the same effects.

“Also, in good methodological studies, they also report if the blinding worked or not by asking the participants after the study.” Balachandran said. “Of course, the doctor is aware that he is giving the sham or the real treatment so there is a high risk of bias. So there is some bias that cannot be completely eliminated even in the most rigorous studies. In short, studies with good methodology should have a well-validated sham treatment and also report if the blinding worked based on the feedback from the participants.”

Balachandran also considered dropouts in a study that can affect its bias.

“This is one aspect that most folks ignore or are not aware of. It is now pretty clear that dropouts in a study could be related to the prognosis,” he said. “This simply means that people who drop out from a study might be the ones who didn’t experience any benefits or may have worsened their pain.

Basically, if people didn’t get better during the study, they would drop out. All that is left for the researchers to work with are those who responded well to the treatment.

“So the people who remain in the intervention group are the ones in which the treatment worked well, and naturally, the group averages tend to be better than it truly is,” Balachandran said. “This becomes more important when one group has greater dropouts than the other group.

“We will never know if the results of a study is the actual truth, but the better the methods, the more confident we are that we are closer to the truth. After all, science is all about finding the truth.”

3. Effect size: does it tell us if a treatment is worth paying for?

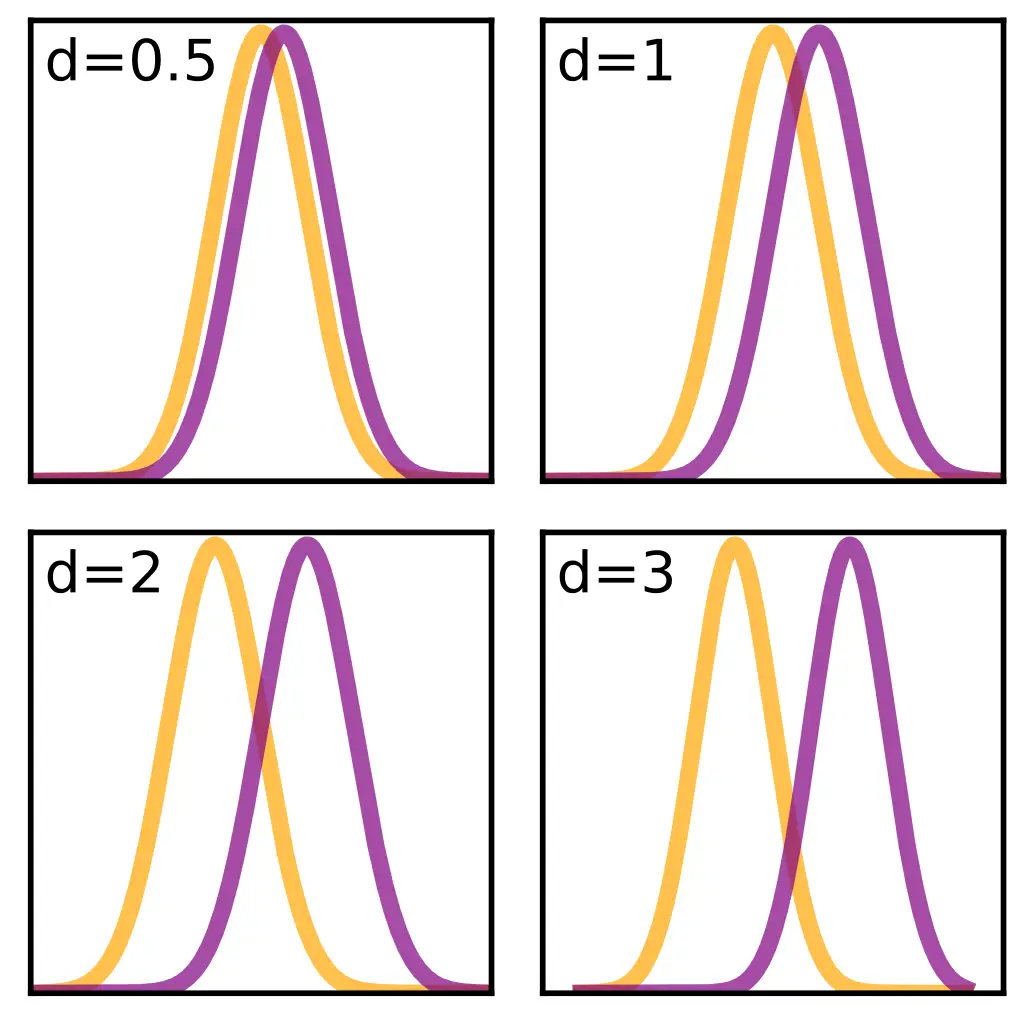

The close the two comparisons, the less differences there are. Image: Skbkekas

In research, an effect size tells us how much difference there are between two treatment groups, and knowing it can help us recognize how effective and efficacious the treatment is.

If a research paper says that patients who were treated with XYZ intervention had less pain than those who had received no intervention or had a different type of treatment, how big was the difference?

After all, researchers could claim a tiny difference between groups can be “better,” in which some people can market that intervention as “effective.”

Effect size, also known as Cohen’s d, is measured on a scale where

- 0.8 is ranked as “high”

- 0.5 as “moderate”

- 0.2 as “low.”

Back to the Moyer’s study on the effect of massage on cortisol levels, the researchers pooled 11 studies on single-dose massage sessions as the first treatment in a series of treatments with a total of 460 participants and found that “[massage therapy] did not reduce cortisol significantly more than control treatments” with the effect size (d) of 0.15.

When they examined eight studies of single-dose sessions with 307 participants as the last treatment of a series, they also found the same result (d = 0.15).

Among multiple-dose massage sessions, they also found low effect sizes (d = 0.12) among 16 studies with a total of 598 participants.

When these studies are split into adults and children, the adults (n = 508) effect size dropped more than 50 percent (d = 0.05).

However, the children group ranked higher with a “moderate” d = 0.052. The last result may seem promising, but Moyer et al. cautioned that this data is based on a tiny number of studies and likely is “vulnerable to the file-drawer threat” where many studies with negative outcomes are not published.

Also, larger effect size does not always mean a treatment is “better,” nor does a smaller effect size mean it is “not very good.” You need to consider context of the data to making better meaning.

For example, if being active regularly can improve mortality by 0.09 over five to six years, this small effect can still save many lives by encouraging people to be more active.

But if a treatment only reduces back pain by 0.09 when compared to standard care or placebo, then it may not be in the best interest for patients to get and pay for that treatment.

4. Clinical equipoise: How much bias are there in the study?

In some ways, manual therapy research is similar to a Mortal Kombat game where one modality is “pitted” against another to see which is “better.” This bias not only may lead them the everything-is-a-nail mentality, it also can skew the outcomes of manual therapy research.

As with any scientific research, the goal is to be as objective as possible, hence the emphasis of clinical equipoise, which is the assumption that one intervention is NOT better than another.

Physiotherapists Chad Cook and Charles Sheets wrote that to have true equipoise, the researchers must have “no preference or is truly uncertain about the overall benefit or harm offered by the treatment to his/her patient. In other words, the clinician has no personal preconceived preferences toward the ability of one or more of the interventions to have a better outcome than another.”

While this may not seem very practical or even realistic in actual research, it’s something researchers should strive for. Even with the best intentions, researchers sometimes unconsciously set up the experiment in a way that favors the tested intervention or undermines the control group.

It’s also possible that the “placement of importance, enthusiasm, or confidence associated with one’s expertise in an intervention” can influence the experiment’s outcome, which also includes how well the patients perceive the treatment.

Having pure personal and clinical equipoise may be unlikely to avoid to do because it’s impossible to blind the practitioner. It’d be like working blind-folded while providing the treatment, which isn’t practical.

5. Can the massage research be applied to hands-on work?

Applying therapeutic exercise research to practice at the 2017 San Diego Pain Summit with Ben Cormack. Photo: Nick Ng

You might have read something about researchers using fruit flies to understand how genetics, behavior, and certain diseases work. Back in the late 1970s to early 1980s, Dr. Christiane Nüsslein-Vollhard, who is a biologist, made some discoveries about how fruit flies grow and develop with her colleagues Dr. Eric Wieschaus and Dr. Edward B. Lewis. She had no idea that their research on Drosophilas could end up being one of the main staple animals that many biomedical research use in the next three decades.

What they did was basic science — research done for the sake of understanding a specific phenomenon with no or little consideration for its real-life applications.

What came after was translational science, using fruit flies for a variety of scientific disciplines, including evolutionary biology and behaviorial genetics that could identify certain genes that increase the likelihood for humans to get a certain disease.

But in manual therapy research, we should be careful about extrapolating basic research to our hands-on practice since the researchers may not often have practicality of their work in mind.

Conversely, sometimes translational research in manual therapy don’t consider basic science and may come up with false positives.

“There is a tendency to not scrutinize basic mechanisms of research through the same critical lens that we do clinical trials,” Dr. Neil O’Connell explained, who is a physiotherapy researcher at Brunel University. “But this is a mistake as the field is troubled by small sample sizes and avoidable biases that are not controlled.”

O’Connell cited a study in 2011 that finds sticking needles in certain parts of the forearm can change how the brain perceives pain. However, such changes does not mean the interventions “work.”

“Brain activation in response to needling neither validates acupuncture nor provides a cogent mechanism for therapeutic action,” he wrote. “That it activates sub-cortical networks involved ‘endogenous pain modulation’ also does not distinguish acupuncture as a possibly effective active treatment since these networks are also implicated in the placebo response.

“It is not that the data in this study tells us nothing important. It adds to an existing body of data regarding how sensory input is cortically processed. But as a study of therapeutic mechanisms, it attributes possible mechanisms to an effect that the best evidence tells us does not exist.”

O’Connell said that somehow finding a physiological effect of a treatment legitimize the intervention, and many therapists and companies would likely market this to the public because research found “something” that seems to “work.”

“We tend to forget that even when a biologically plausible mechanism exists, it is not a given that it will translate into a meaningful clinical effect,” he said. “Think of the scale of failed new pharmaceuticals where the biological plausibility work all looked good. None of this is to denigrate the value of various types of evidence. The danger lies in taking any evidence, not matter how removed from the patient, as some form of tacit legitimization of your therapy du jour.

Researchers might take a finding in a cell or animal model and use it as evidence to support a treatment’s effectiveness. In reality, the effect may likely in indirect.

“They will often presume that any evidence of some physiological change is evidence that a treatment is plausible,” O’Connell said.

6. Do positive outcomes validate a treatment?

Tying back to outcomes, when we see our patients feel better after a treatment, we often give credit to our treatment for making them feel better. But this alone cannot be a validation to the positive (or sometimes negative) outcomes because outcomes only measures outcomes, not the effects of the intervention.

This is because many factors other than the intervention can affect the outcome, such as the non-verbal interactions between the therapist and the client or patient, the natural regression of pain, and patients’ beliefs and prior experience to the intervention and interaction with their previous therapist.

Sometimes a positive outcome can happen without any interventions; and we can also say the same thing about negative outcomes which doesn’t always mean that the intervention “sucks.” It could have gotten worse without the intervention.

Relying on outcomes can also blind us from acknowledging those who do not respond well to the treatment, which is a demonstration of survivorship bias—we notice and acknowledge successful outcomes while sweeping aside unsuccessful ones.

Even though high quality randomized-controlled trials are the best method to use, Herbet et al. suggest that we should avoid the being extreme on either side of the decision-making process, where one side relies on outcomes and the other side relies strictly on randomized controlled trials. We need both.

When there is no good available evidence, clinical outcomes are likely all we get to use. That could be risky, depending on the nature of the problem and the type of intervention.

However, when randomized-controlled trials “provide clear evidence of the effects of an intervention from high quality clinical trials, clinical outcome measures become relatively unimportant and measures of the process of care become more useful,” Herbet et al. wrote. “When evidence of effects of interventions is strong, we should audit the process of care to see if it is consistent with what the evidence suggests is good practice. When there is little or no evidence, we should audit clinical outcomes.”

When it comes to considering whether an intervention works or does not work, we should take our time to examine the existing evidence and check our biases.

While it’s quite overwhelming to see the huge complexity and interactions among different factors that make up a research paper, it gets easier when we get familiar with recognizing its strengths and weaknesses, like building endurance for a marathon.

We can avoid being misled by news headlines and blogs that may misinterpret or exaggerate a study. Also, we can appreciate the larger body of literature that gives us a better picture of a topic, such as whether massage therapy actually does decrease cortisol or not.

A native of San Diego for nearly 40 years, Nick Ng is an editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine, an online publication for manual therapists and the public who want to explore the science behind touch, pain, and exercise, and how to apply that in their hands-on practice or daily lives.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a B.A. in Graphic Communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014.

When he is not writing or reading, you would likely find him weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, or exploring new areas to walk and eat around Southern California.