You may not need to stretch to become more flexible when you hit the gym or before playing a sport. Emerging research in the last two decades found that strength training is just as effective as stretching to improve your flexibility, and stretching may not be as ‘great’ or a requirement as many personal trainers, coaches, and yoga teachers claim.

A team of researchers, led by Dr. José Afonso from the University of Porto in Portugal, reviewed 11 qualified studies with a total of 452 subjects and found that both strength training and stretching work just as well in increasing joint range of motion.

They concluded that strength training and stretching “were not statistically different in [range of motion] improvements” in the short run.

“You don’t really need much flexibility if the goal is to perform daily activities comfortably,” said Afonso. “For [some] sports, flexibility becomes more important. But stretching is not the only way to improve flexibility. Stating that flexibility is important does not imply that you must stretch. You can do strength training instead.”

Most of the subjects were women and the hip joint was the most measured body part, followed by the knee and shoulder. There wasn’t much focus on other joints so no one really knows if other joints like the ankles and spine have similar effects.

“Flexibility isn’t irrelevant for health and function,” said Dr. James L. Nuzzo, who is an American exercise scientist currently living in Perth, Western Australia. “However, I think practitioners should explain to patients and clients that not all aspects of physical fitness are equally important.”

In a 2020 paper published in Sports Medicine, Nuzzo found that flexibility is not predictive of mortality. Instead, body fat composition, muscular power and endurance, and cardiovascular endurance are predictors of mortality.

“The focus of exercise programs for most individuals should be on cardiovascular endurance and muscle strength,” Nuzzo said. “These two components of fitness correlate strongly with health and function. Exercise programs that aim to increase these two components will likely increase flexibility along the way.”

Conversely, if you just focus on stretching, you are unlikely to improve your strength and cardiovascular health. So if you want to maximize your gym time, strength and cardio should be top priorities.

How does strength training get you to be more flexible?

Strength training can help you become more flexible by placing stress upon the muscle fibers as they elongate, such as during an eccentric contraction. An example would be when you lower the weight during a hamstring curl, barbell squat, or push-up.

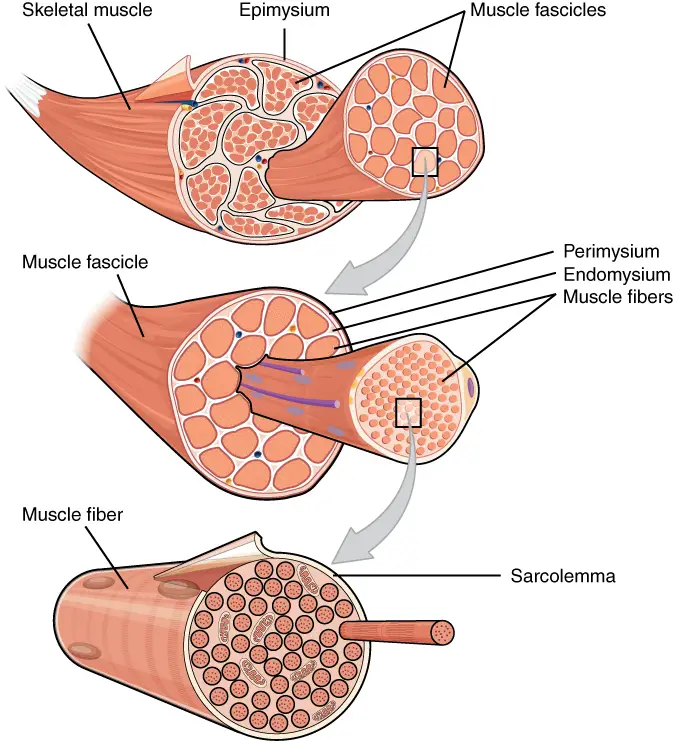

“Strength training involves alternating shortening and stretching, so think of strength training as dynamic stretching with extra loading,” Afonso explained. “Strength training can increase fascicle length—especially eccentric strength training—and favorably alter pennation angles, allowing for greater excursion even when fascicle length isn’t altered.”

He also said that strength training can help muscle groups synchronize their contraction rate better and increase their stretch tolerance, which can influence how you can be more flexible.

“What we don’t know is if strength training is enough to improve flexibility in sports requiring extreme range of motion, like gymnastics,” Afonso said.

A large body of research has found that eccentric strength training of the hamstrings can increase the fascicle length of the biceps femoris muscle. These fascicles are bundles of muscle fibers that are wrapped by connective tissues. Eccentric strength training also may change muscle length by increasing muscle excitability (ability for a muscle to respond to a stimulus, like stretching or loading), which is influenced by the number of motor units and various neural activities.

Photo: OpenStax, Version 8.25 from the Textbook OpenStax Anatomy and Physiology, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

The lengthening of fascicles may likely increase stretch tolerance and reduce the strain on sarcomeres (basic contractile unit of a muscle fiber) when they are better aligned. This may also help reduce the risk of getting a hamstring strain.

Concentric muscle contraction—shortening of the muscle—can also increase flexibility when it’s done with a full range of motion. However, researchers have found that partial range of motion increases cross-sectional areas of the vastus lateralis muscle of the thigh and specific strength adaptations.

Could this work for other muscles? Maybe. The body of research indicates how the muscle fibers are aligned and the type of muscle fibers may influence how flexible you can get.

“We tend to associate strength training with the concentric phase of the exercise. I think this biases our thinking in terms of associating strength training with increased muscle bulk and strength rather than increased flexibility,” Nuzzo said. “I think we often forget about the eccentric phase of strength training exercise, [which] is likely responsible for the increased joint range of motion after strength training because it is during this part of the exercise that the muscle-tendon unit is most-lengthened.

“To put it another way, static stretching does not hold a monopoly on the lengthening tendons and muscles.”

Basic strength exercises to get you more flexible

Since there’s no evidence (yet) that says one type of strength training is better than another for getting you more flexible, you can do almost any exercise you like. Nuzzo said that the main factors that likely affect flexibility would be the range of motion you do during strength training and how consistent you are in your workouts.

In other words, the more range of motion you do during strength training, the more likely you will increase flexibility. The method or type of equipment isn’t that important.

Afonso also agrees. “Currently, we cannot state which strength training methods and tools are better for improving range of motion,” he said. “We don’t know the ‘ideal’ dosage or the configuration of the programs that best promote range of motion gains. And there are studies showing [benefits of] using machines, free weights, resistance bands, bodyweight, etc., so probably the most important is to find what suits you best.”

“And why choose, anyway?” Afonso added. “Each tool has different advantages and disadvantages. Why not use all those tools instead of picking just one?”

Common strength exercises include:

- Squats

- Push-ups (and its many variations)

- Pull-ups (and its many variations)

- Cable rotations

- Deadlifts

- Lunges (and multi-planar options)

- Shoulder press

- Lat pulldowns

One-Arm Row with Hip Rotation

Barbell Front Squats

Kettlebell Goblet Squats

Deadlifts

Multiplanar Lunges

Can becoming more flexible prevent injuries?

Contrary to popular belief, stretching or being more flexible doesn’t necessarily prevent or decrease your risk of injuries much. In fact, different types of stretching have different benefits and drawbacks.

Many people think of stretching as static stretching, which is holding a stretch for about 30 seconds. But that isn’t the only type of stretches.

Dynamic stretching, which is moving your muscles and joints repetitively within your full range of motion, may be a better option for you to do before you workout than static stretching. It’s more sports specific that prepares your nervous and muscular systems to perform more specific movements.

For example, if you’re going to do some heavy squats, doing a few reps of bodyweight squats before you lift would be one example.

But research finds some conflicting results between stretching and injury prevention or reduction. A 2008 systematic review finds that static stretching does not prevent overall injuries, but there are some studies that say it may prevent some muscle and tendon injuries.

The ones that find no reduction in injuries refer to non-musculoskeletal injuries, such as bone fractures and circulatory injuries, which static stretching have no effect on.

“Being extremely loose can be just as bad as being extremely stiff. For most activities, there’s no increase or decrease in injury, but being outside of that bell curve causes some issues,” said Dr. Allan Bacon, who is the cofounder of Maui Athletics in Hawaii.

Dr. Allan Bacon, cofounder of Maui Athletics. Photo: Maui Athletics

In fact, getting too flexible may increase the likelihood of injury, particularly the knee. A 2010 systematic review and meta-analysis of eight qualified studies found that an average of more than 20% of people with “extreme hypermobility” in the knee suffered an injury. The rate goes as low as about 12% to nearly 30%—compared to about 3% to 7% of those with no hypermobility.

However, there is not much difference between hypermobility in the knee and ankle. The researchers reasoned that ankle stability relies on “active” (muscles, tendons) and “passive” (ligaments) mechanisms, but the knee relies more on the passives for stability.

“Usually when you have people who are hyper-flexible, what you don’t see is the stability in their end ranges of motion,” said Beth Bacon, who is the cofounder of Maui Athletics and trains mostly Olympic athletes. “We have weightlifters who are hyper-flexible in their shoulders. When they lock out a snatch, they are super unstable. They might get that bar up all the way back behind their head, but they have difficulty stabilizing it.”

Nuzzo wrote in the paper that newer research might find having a middle range of flexibility might be optimal for various activities. “This would make flexibility akin to body composition…where both low and high scores reflect poorer fitness,” he wrote.

Can flexibility improve sports performance?

Whether getting more flexible can help you improve your sports performance would depend on what type of sport you’re training for. Current research finds static stretching has little to no effect on injury prevention nor does it impair strength and power.

The authors of that research summarized that static stretching for less than 60 seconds has “trivial negative effects” on strength and power output immediately after the stretching.

When static stretching is mixed with dynamic warm-ups, it may even lower the risk of certain types of injuries, depending on the activity that you play, such as soccer, gymnastics, and taekwondo. They recommended that static stretching should be “part of a warm-up component in recreational sports due to its potentially positive effect on flexibility and musculotendinous injury prevention.”

However, for “high-performance” athletes, such as American football players and track and field runners, they should take extra precautions with static stretching since it may likely reduce the power output.

In practice, Allan Bacon said that athletes usually maintain enough flexibility to perform, and that’s all they often need.

“Powerlifters have a tendency to be extremely flexible within the range of motion they work in but not flexible beyond that,” he said. “That’s why they get that reputation of being ‘stiff.’ But in their sport, [the stiffness] is beneficial because it allows more concentric strength generation and maximal strength.”

Some stretching might be important to a fresh athlete who might need to focus on mobility and pain tolerance. It’s the type of discomfort that you often get when you stretch beyond your comfort zone. These athletes, according to Allan, need to get to a certain “depth” of flexibility to gain the benefits of the sport that they play.

“There’s a lot of the argument about whether stretching is giving people benefits because of actual [structural] changes of the muscles or work through pain,” Allan Bacon said. “I think it’s a bit of both.”

So is flexibility important?

Nuzzo stated that flexibility is still important in sports and daily activities, but sports organizations, like ACSM, and many fitness professionals may have given it too much credit for many decades. It should be “demoted from a major component to perhaps a secondary component” in fitness for most populations.

What Nuzzo isn’t saying is that flexibility is irrelevant and should be tossed into the garbage can. In fact, the critique does not discount the benefits of dynamic stretching. The time you spend working out should focus more on strength and cardio than stretching.

“I was interested in this topic when I discovered two studies that reported flexibility does not predict all-cause mortality,” Nuzzo said, who had also dug through some rabbit holes on flexibility research. “I found this interesting because other aspects of fitness predict mortality (e.g., muscle strength, cardiovascular endurance). Yet, few people were stating this explicitly, and I thought it was important to present the case for retiring flexibility as a major component of physical fitness because stretching programs will do little to resolve the overweight and obesity issue in the U.S. and elsewhere.”

So if you want to be more flexible, stretching is not the only way to achieve it.

“Provide options! People should not be forced to perform stretching if they don’t like to do it. They can use strength training to improve flexibility,” Afonso said “If you don’t stretch but [you do] strength training, you will improve range of motion. For now, I would advise to use full range of motion if that’s the goal. [Lets’] help break the myth that strength training will reduce your range of motion! It will actually improve it!”

Feature photo: courtesy of Maui Athletics.

A native of San Diego for nearly 40 years, Nick Ng is an editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine, an online publication for manual therapists and the public who want to explore the science behind touch, pain, and exercise, and how to apply that in their hands-on practice or daily lives.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a B.A. in Graphic Communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014.

When he is not writing or reading, you would likely find him weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, or exploring new areas to walk and eat around Southern California.