Exercise often draws mixed reviews from those with hypermobility spectrum disorders (HSDs), often with anecdotal and sometimes research based justification. Many people under that spectrum have had negative experiences with various traditional means of health management. However, there is hope for those with HSDs, including Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, when provided with appropriate guidance.

Is hypermobility syndrome the same as Ehlers–Danlos?

Joint hypermobility syndrome is considered an older way of referring to HSDs in the hypermobility research and clinical realms. Previously, joint hypermobility syndrome and hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (hEDS) were almost impossible to tell apart. Now a revised framework has been developed for a wide range of classifications of hypermobility, including—but not limited to— asymptomatic (meaning no pain or other symptoms) joint hypermobility to the most severe cases being labeled as hEDS.

Understand that HSDs can be very complex and often are the exception to the rule of what most clinicians encounter, which is a potential contributing factor to why so many of them may mishandle these situations and traumatize patients with HSDs.

Does exercise (strength and aerobics) have different effects between the two?

Technically, aerobic and anaerobic exercises can have similar effects, but these forms of exercise are often used differently. In aerobic exercise, many people use it for improving heart function and endurance while strength training is often used for muscular strength or building muscle mass. However, both can potentially create at least some of the effects of the other.

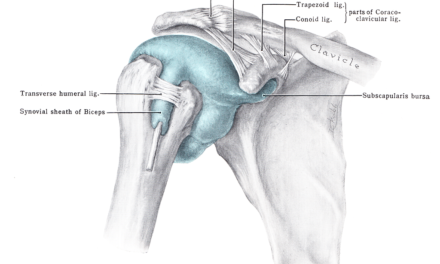

For people with hEDS, it’s often recommended to perform both aerobic and resistance training, (e.g. shoulder strengthening and stability exercises), particularly for those who have a common concurrent diagnosis called postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS). Oftentimes, exercise protocols for POTS include a slow structured regimen for aerobic and strengthening exercises.

Is strength training good for hypermobility and EDS?

Physical therapist and strength coach Jason Bouwkamp, a hypermobility specialist who completed his doctorate of physical therapy from the University of Florida and subsequent orthopedic residency at UFHealth Orthopaedic & Sports Medicine Institute, who currently works in the Portland, Ore. area, thinks that there are many reasons why strength training is good for hypermobility and EDS.

“At the simplest level, a stronger person has more reserves to deal with more physical stresses,” he said. “There’s also the enhanced self-efficacy, body awareness, [and] muscular coordination, meaning the muscles are working with each other in concert, and often an improved capacity to deal with their POTS symptoms.”

Bouwkamp added that many forms of resistance training that resemble high-intensity interval training can benefit those with POTS because they involve a short period of stress followed by a rest period, so it can often serve as a substitute to cardio-aerobic exercise for people with POTS.

“A lot of these people are victims of the medical system, and as a result are disempowered,” Bouwkamp said. “They become empowered and more mindful of their movements. It’s not necessarily they’re moving with perfect form, but they’re able to accomplish a lot more as a result. Getting involved in strength training independently leads to joining a strength-oriented gym, which leads to a greater sense of community as they have more people to connect to.”

Strength training has been shown to be potentially helpful for those with HSDs. It makes sense they would benefit from something to address their decreased strength and tolerance to physical activity but there are some things to consider.

Amber Whiting of Portland, Ore., was diagnosed with hEDS and said that strength training didn’t help her at first, but eventually, it allowed her to go back to work full time and advocated for patients with hEDS.

“I’m a Mom, I can play with my son, I can walk up and down stairs, I can go grocery shopping and not pass out at the grocery store,” she said. “I literally had that happen [prior to starting her current episode of physical therapy care], I passed out at a grocery store and it was scary.”

Whiting’s physical therapy routine includes a great deal of strength training, but a key distinction with her routine is it was tailored to her capabilities and needs with consideration of sustainable progress instead of an approach based solely on the clinician’s or coach’s expectations and assumptions.

“Learning a lot about where my limits are and respecting that space and from there pushing gently and gradually has made a huge difference,” she added. “Now I’m doing highly specialized physical therapy and that’s made the biggest difference in terms of exercise.”

Is Pilates good for hypermobility and EDS?

“I often find that when doing some of the smaller ‘activation’ movements, people report that it helps them to relax and ease the tension out of the larger muscles that usually take over,” said physiotherapist Aisling Heavey, who also teaches mat Pilates in Dublin, Ireland. Photo courtesy of Aisling Heavey.

Some physical therapists who work in the realm of hypermobility spectrum disorders are often certified in and use Pilates for people with HSDs.

Aisling Heavey, who is a physiotherapist in Dublin, Ireland, and a certified Pilates instructor via the Australian Physiotherapy and Pilates Institute in Pilates Matwork, thinks that it is a “great entry into exercise” for people who have difficulty in moving because of pain and joint instability. She also works with hypermobile patients.

She said that research has shown that people with hypermobility can strengthen at the same rate as those without.

“We can start working on smaller movements and body awareness, as well as control, in a safe setting,” she said. “I often find that when doing some of the smaller ‘activation’ movements, people report that it helps them to relax and ease the tension out of the larger muscles that usually take over.”

Heavey described Pilates as a way to help people “feel safer and more confident” with exercise.

“There has been some research around barriers to exercise and beliefs around exercise in these populations, and guidance by a physiotherapist has been shown to be helpful in getting people exercising and moving more,” Heavey said. “However, it can take twice as long due to the other factors involved such as fatigue, pain, deconditioning and autonomic dysfunction.”

Heavey described Pilates as a way to help people “feel safer and more confident” with exercise, but it can take twice as long because various factors can impede progress. Photo courtesy of Aisling Heavey.

What strength exercises are good for hypermobility and EDS?

Bouwkamp cited six broad movement patterns or tasks (crediting prominent coach Dan John as his source) that shouldn’t be neglected with this population:

He said that not everyone can do the same exercise, but these general movement patterns work on the entire body.

“The reason these exercises span the entire body is because you have the support limbs working in isolation while the moving limbs work dynamically,” Bouwkamp said, “and that allows them to interact with their environment and learn intermuscular coordination.”

While he prefers to use barbells, kettlebells, and body-weight exercises, others can use sandbags, dumbbells, bands, clubs, and other forms of equipment with positive outcomes.

“The important thing is that they’re moving, mindful of moving, and try to progress,” he said. “It is important to keep in mind each person is different and modifications are often needed for each person to find an appropriate starting point, in terms of exercise, for themselves.”

For example your squat might be just working on sitting down, standing up, or even shifting in a chair. Still, one may need the help of a professional if finding that point is too difficult.

Is yoga good for Ehlers–Danlos syndrome?

Yoga is often a controversial subject in the treatment of HSDs, including hEDS and other forms of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. If misused, yoga could create some challenges for people with these conditions, but when it‘s applied properly, it may benefit some of them.

Dr. Catherine Lewan not only has hEDS but she is also a physical therapist in Chicago, Ill., who is certified in STOTT Pilates, Shambhava yoga, and prenatal yoga. She had learned Pilates at age 12 from physical therapists.

“Hypermobile individuals need a lot of support with motor learning as the muscular system has to learn to support joints that move more,” Lewan said. “Having more movement requires a high level of muscular coordination and endurance to support that movement. Pilates emphasizes motor control and endurance using body weight or light resistance, which meets this need and may be better tolerated than heavier lifting programs. Pilates also aims to strengthen proprioception, a type of body awareness that is often lacking in people with hypermobility.”

Yoga is about creating balance, and encouraging more mobility in someone who is already hypermobile is strengthening an imbalance from a yogic perspective,” said physical therapist Catherine Lewan who practices in Chicago, Ill. Photo courtesy of Dr. Catherine Lewan.

Proprioception is often a key point of emphasis in the rehab of people with HSDs as it is something people with HSDs tend to struggle with. The term was originally defined by Sir Charles Sherrington as “the perception of joint and body movement as well as position of the body, or body segments, in space.”

“I also utilize yoga therapy, which surprises many of my clients who have been told they should never do yoga because they are hypermobile,” Lewan said. “This is likely due to the misconception that yoga is a tool for becoming more flexible, which, in the West, we take [it] to an extreme. Hypermobiles do need to use caution with group yoga classes or instructors [who] are pushing them to do contortion-like poses. Yoga is about creating balance, and encouraging more mobility in someone who is already hypermobile is strengthening an imbalance from a yogic perspective.”

Lewan uses yoga to help her clients find ways to move within a mid-range, which promotes strength, body awareness, proprioception, motor control, and a sense of safety.

“Yoga is also a powerful tool for autonomic regulation and may be a helpful adjunct to a stress or pain management program,” she said.

Meanwhile, Whiting said that her aunt was a yoga teacher “before it was cool” and has been doing it since about 5 years old.

“I did it all the time, and when I was going through college, I would take a yoga class every term and I would get injured often,” she said. “I realize now I was taking these classes in the early morning when it was cold [many people with hEDS don’t do well with extreme weather], and some of the instructors would tell you to be mindful of things but then push harder in the poses.

“I still love yoga. I’ve just learned to actually respect where my bodies boundaries are.”

Patients’ perspective of strength training with hEDS

Ultimately, stories are what most resonate with us. People with hEDS or HSDs are likely going to be more interested in what other patients say about what forms of exercise helped them than just hearing from various providers.

Meaghan Creech, another patient with hEDS from Portland, Ore., described her past experiences with exercise prior to strength training “this [her clinical presentation] is definitely something my immediate family thought was just a character flaw.

“Even from an early age, I used to dread any form of physical activity,” Creech said. “My mother would have to leave me at the library, which was halfway between our house and the grocery store because I couldn’t tolerate the walk and bad things would happen.”

She had to run on an injured knee during high school because no one would believe her that her knee was dislocating until her knee had so much damage that she had to get surgery to repair it.

She would “physically crumble” when she tried out for sports. Her symptoms kept troubling her as she grew older to the point that Creech had to drop out of college because sitting in a chair for an hour flared up her symptoms.

To Creech, strength training is a way to establish what one can do now and then set goals accordingly to progress one’s capabilities.

“It seems like it gave me a structure to do things tangibly on a really more accelerated pace than the POTS protocol,” she said. “I was really in the middle of the POTS protocol when I started working with my PT, and using strength training is what really helped me to get from 0 to 1 [meaning make notable progress].”

Since she started strength training, Creech also noticed that it helped improve her relationship with self-care and led her to start making lifestyle changes to enhance her sleep and diet.

“I was surprised by the cognitive benefits and the parasympathetic benefits, [which makes] it easier to get to a rest-and-digest place and how much that reduced the load the anxiety placed on me by my body being in a bad physical place,” Creech said. “It allowed me to be able to tolerate sitting in a classroom for longer than an hour, like I’m back in school now full time because of strength training, and I have a 4.0. It also allowed me to stand for long periods and walk for at least an hour at a time.”

Feature photo: Andres Aryton

Mike Mahker, PT, DPT

Mike Makher is a physical therapist (DPT) and exercise instructor from Portland, Ore., with specialized training and experience in helping those dealing with hypermobility spectrum disorders and/or persistent pain. He graduated from CUNY’s College of Staten Island Doctor of Physical Therapy program and received his Bachelors of Science in Economics from the Pennsylvania State University.

He’s also received Improv Comedy training at the Philadelphia Improv Theater, ComedySportz Portland, and the Upright Citizens Brigade.