A SLAP tear is a tear of the labram cartilage that lines the shoulder socket, often involving the attachment of the biceps tendon to the labrum.

SLAP tears (Superior Labrum Anterior and Posterior) can be acute, chronic, or degenerative and often occur with other shoulder injuries, such as posterior labral tears, Bankart lesions, or rotator cuff injuries. About 6% and 12% in the general population has a SLAP tear.

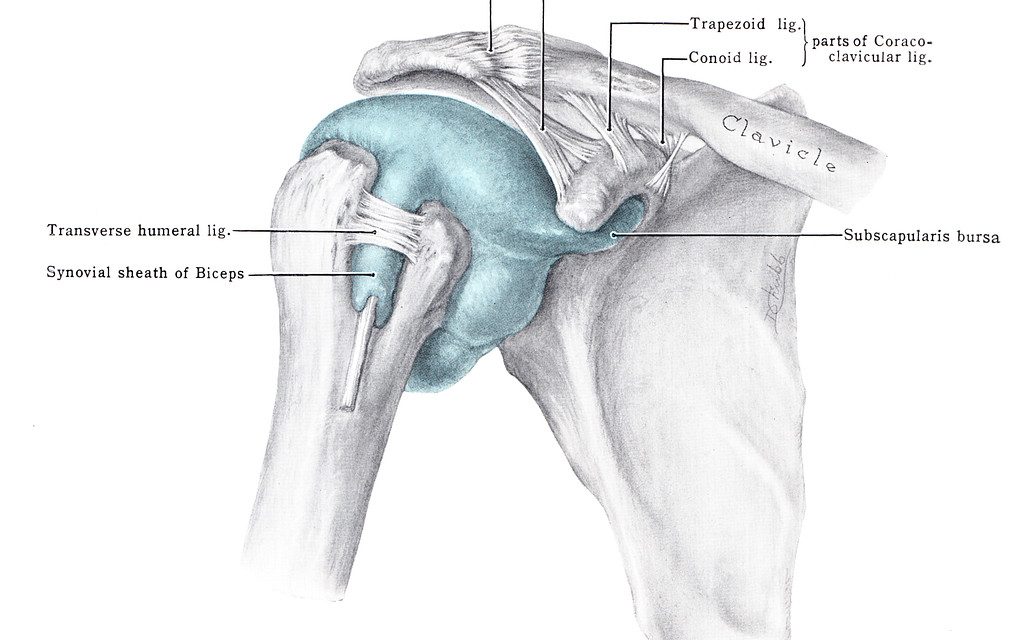

Shoulder joint anatomy

The shoulder girdle consists of four joints—glenohumeral, acromioclavicular, sternoclavicular, scapulothoracic—working together to create the most flexible joint in your body. These joints are formed by the humerus, scapula, clavicle, and ribs and allow flexion/extension, abduction/adduction, and internal rotation/external rotation.

The rotator cuff muscles stabilize the shoulder, which are the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis. They also externally and internally rotate the joint (think throwing motion), but arguably, their more important job is keeping the humeral head in place and out of the way during movement.

The rotator cuff acts like the strings of a marionette to move the humeral head in and out of positions to create smooth, coordinated, unobstructed motion. If not for the action of the cuff, the humeral head would butt up against the acromion process with every arm raise.

The nerve supply to the shoulder originates in the brachial plexus. The suprascapular nerve passes below the suprascapular ligament along with the suprascapular vessels. It has several branches that supply supraspinatus and surrounding muscles.

The suprascapular nerve then travels through the spinoglenoid notch where it branches off to innervate infraspinatus.

Causes of a SLAP tear

Historically, SLAP tears were thought to be unique to overhead athletes. But over the past 20 years, this diagnosis has become more common in the general population as researchers have discovered labral pathology is quite common. Acute tears can happen during an errant baseball throw or a fall on an outstretched arm (FOOSH injury). Conversely, chronic or degenerative tears can occur as part of the wear-and-tear process associated with normal aging, from a job or sport that requires repetitive motion.

Injuries

Injuries to the labrum are often associated with overhead athletes. The deceleration phase in baseball, tennis, volleyball, and other sports is often the cause of injury. In this position, the shoulder is abducted and maximally externally rotated which stresses the connection of the biceps tendon to the labrum; this results in a “peel-back” mechanism of injury.

Normal aging

The labrum can get worn down by normal daily activities leading to tearing or fraying. A 2014 systematic review found that when compared to younger patients, those over age 40 who had their SLAP tears surgically repaired experienced more pain and stiffness after the surgery. The group noted that patients may do better with biceps tenotomy or tenodesis, which suggests at least some portion of the pre-operative symptoms may originate in structures other than the labrum. Other research groups have identified the long head of the biceps tendon as a potential source of anterior shoulder pain as well.

The presence of a SLAP tear on imaging increases with age, but this does not mean the labrum is the source of pain or symptoms. A 2016 study found that 55% to 72% of 53 asymptomatic middle-age adults had SLAP tears. These rates are consistent with findings for asymptomatic structural abnormalities of the hip, knee, and spine. The researchers cautioned that such labral tears may be “normal age-related findings” and avoid overtreatment.

Overuse or repetitive movements

Sports and occupations that involve repetitive motion at the shoulder, such as swimming or electrician work, may also lead to SLAP lesions. SLAP tears happen in non-athletes as well; dislocation/subluxation of the humeral head, internal impingement, heavy lifting, and posterior capsule tightness may also lead to SLAP tears.

Some patients often report deep, progressive shoulder pain when in the overhead position. In this position, the biceps tendon is being stressed anteriorly while the humeral head glides posteriorly which creates the “peeling” of the labrum.

Prevalence and symptoms

Symptoms of a SLAP tear include:

- Deep, aching pain in the shoulder joint, especially with arm movements

- Popping, clicking, catching, locking or grinding sensations in the shoulder

- Decreased range of motion and shoulder instability

- Pain when lifting or carrying objects or moving the arm overhead

- Shoulder weakness and decreased strength

SLAP tears may be more prevalent in the dominant shoulder of men in their late 30s. In 1995, researchers in Southern California examined 140 arthroscopic shoulder cases and reported pain was the most prevalent SLAP tear symptom, followed by catching or grinding. More than 40% of SLAP tears were associated with rotator cuff tears. One-third of the cases were isolated labral injuries.

Patients may be unable to recall when the pain started. In the case of a fall or sports injury, they may easily relay the history of the injury, but if the tear is degenerative, the onset of symptoms may have been gradual. Patients with SLAP lesions often have difficulty sleeping, particularly if their preferred sleeping position involves having their injured arm overhead. The presence of mechanical symptoms will make the savvy clinician suspicious of a SLAP tear.

Types of SLAP tears

Certain classifications of SLAP tears are associated with particular mechanisms of injury.

Type I

Age-related degenerative tears are generally type I lesions, which involve fraying with no clear tear at the superior aspect of the labrum and an intact biceps tendon.

Type II

Repetitive overhead motions are often type I or II tears, which involve labral fraying with involvement of the biceps tendon. The three subcategories of type II lesions are:

- Type IIA: an anterosuperior labral tear

- Type IIB: a posterosuperior labral tear

- Type IIC: a superior tear that extends anteriorly and posteriorly

Type III

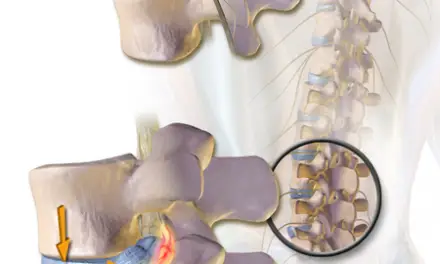

Type III lesions are bucket-handle tears of the superior labrum where the central piece of the tear is displaced into the glenohumeral joint (similar to a bucket-handle meniscus tear).

Types III, IV, and V are associated with falls on an outstretched arm.

Type IV

Type IV tears are similar to type III but extend to the biceps tendon.

There are also levels V to X tears, but these are the rarest of the rare cases. Type V and VII may be found in those with glenohumeral instability following acute injury.

Prognosis of a SLAP tear

Surgical and non-surgical SLAP tear cases have a good prognosis when careful attention is paid to who undergoes labrum surgery. Research shows those with isolated unstable Type II SLAP lesions can anticipate good to excellent results and a successful return to their prior level of activity. These favorable outcomes held true regardless of age, although older patients needed longer to achieve their goal. Some patients had a small range of motion deficits, but final outcomes did not seem to be affected. Among athletes undergoing Type II SLAP repair, nearly 75% returned to their pre-injury level of competition. Among those who reported a discrete traumatic tear, 92% made a complete return.

There’s little evidence beyond case reports regarding the effectiveness of conservative management of SLAP tears, but there is reason to be optimistic. Significant decrease in pain, improved quality of life, and similar return to activity as seen in surgical patients have all been reported. Those who fail conservative management due to continued pain and functional limitations should consider surgical intervention.

Diagnosis of a SLAP tear

Patients with SLAP tears often report diffuse pain and mechanical symptoms such as clicking or popping when moving in and out of the overhead position. Depending on the extent of the tear, they may report instability or feelings of their humeral head subluxating. Though patients with SLAP tears may have pain at night if they sleep with an arm overhead, they do not generally report the pain when lying on the involved side that is typical of patients with rotator cuff tears.

During the physical exam, most patients with SLAP lesions will report pain with passive range of motion when the shoulder is abducted 90 degrees and externally rotated at 90 degrees. Those with isolated SLAP tears may be strong during resisted testing; if rotator cuff pathology is present, the patient may have associated weakness in these muscles. Clinicians should rule out instability prior to using special tests to determine the presence or absence of a labral tear to avoid exacerbating symptoms or creating additional injury.

Several shoulder labral tear tests can determine the presence of a tear including:

- O’Brien’s active compression test,

- Grind test, Speed’s test

- Clunk test

- Anterior slide test

- Biceps load I and II tests

- Pain provocation test.

Although these tests are helpful in determining the presence of labral pathology, their findings can be inconsistent and none is particularly good at identifying labral tears on its own; also, these tests may not be accurately reproduced among examiners.

Although ten types of SLAP tears have been identified, there is some controversy over whether these should all be considered SLAP versus extensive labral abnormalities in their own right. There is no clear evidence that all ten types of injury can be identified on imaging, but many surgeons would be familiar with types I to IV.

Treatment

Treatment options for a SLAP tear are typically considered based on:

- Severity of the tear

- Age

- Activity level

- Presence of other associated injuries,

- Failure of non-surgical treatments, such as physical therapy and anti-inflammatory medications

Surgery

Surgery for a SLAP tear is typically arthroscopy. Type I lesions often require debridement only. In other types of tears, the primary surgical goal is to reattach the biceps tendon to the glenoid rim and to remove any tissue fragments that may be associated with a type III or IV tear.

Indications for surgery include those with large concomitant rotator cuff tears and those with mechanical symptoms such as clicking, popping, or feelings of instability. Generally, type I and III require debridement only while II and IV undergo repair.

Some patients with age-related degeneration may not be appropriate candidates for debridement or repair. The labral fraying seen on imaging is part of the normal aging process, and they often fare better with restored range of motion, improved strength, postural education, and activity modification.

Injections

Corticosteroid injections are not typically successful in patients without an intact labrum. Despite some evidence that conservative management can be successful, there’s no current literature supporting the use of injection in these patients.

As with any injury or illness, consult with a physician or qualified medical professional to determine the best personal course of treatment.

The ideal treatment for a symptomatic labral tear in patients older than 40 is unclear because research has shown these patients do well with biceps tenodesis or tenotomy, which suggests the pain may be coming from the biceps tendon rather than the labrum.

A 2014 systematic review noted that these alternative procedures have shown favorable outcomes in patients with isolated labrum tears and those having a simultaneous rotator cuff repair. Juli Boyer, who is a physician assistant at the Orthopaedic Speciality Institute in Orange County, California, noted that in her sports medicine based practice, her patients often worry about post-operative pain and stiffness. However, they seem to have more favorable outcomes with biceps tenodesis than traditional labral repairs.

“A lot of patients are eager to go the surgical route without even thinking about their potential success with conservative management,” Boyer remarked, who sees many patients benefiting from physical therapy alone. “I encourage every patient to exhaust their conservative management options before considering SLAP tear surgery.”

SLAP tear and massage therapy

Like most types of joint pain, massage therapy could help with reducing the painful symptoms of a SLAP tear. It may help your shoulder feel looser and feel more confident in increasing your range of motion. Massage therapy could help you sleep and move better, which in turn could improve your recovery and reduce pain.

Massage therapists should be well-versed in the biomechanics of the shoulder when working with people with SLAP tears.

Pectoral muscles

Soft tissue mobilization in the supine position should target the pectorals, specifically pectoralis minor, which attaches to the coracoid process. Tightness of this muscle will create anterior tipping of the scapular and close down the subacromial space.

Internal rotators

Working on the internal rotators may also be necessary to decrease the rounded shoulder that can result from the bracing position used with a painful shoulder. The subclavius region should also be addressed, which is responsible for stabilizing the clavicle while the shoulder moves.

Stabilizing muscles

The scapular stabilizers and postural muscles may be addressed in a prone or side-lying position. These muscles may become short and tight over time as those with a SLAP tear avoids the pain and symptoms caused by the overhead position. Massage therapists should ensure their patients have the muscle length to create smooth, coordinated upward and downward rotation of the scapula.

Further reading

Shoulder “abnormalities” May Not Always Be a Cause of Pain or Disability

How Massage Can Treat Chronic Pain

Penny Goldberg, DPT, ATC

Penny Goldberg, DPT, ATC earned her doctorate in Physical Therapy from the University of Saint Augustine and completed a credentialed sports residency at the University of Florida. She is a Board Certified Clinical Specialist in Sports Physical Therapy.

Penny holds a B.S. in Kinesiology and a M.A. in Physical Education from San Diego State University. She has served as an Athletic Trainer at USD, CSUN, and Butler University.

She has presented on Kinesiophobia and differential diagnosis in complicated cases. Penny has published on returning to sports after ACL reconstruction and fear of movement and re-injury.

Outside of the clinic, Penny enjoys traveling, good cooking with great wine, concerts, working out and playing with her dogs.