It wasn’t hard to find Kris Leong among the crowd outside of the Amsterdam Centraal Station on my first visit to the Netherlands on a cloudy day in April 2018. She rolled toward me on her red scooter—her “Batmobile”—wearing a gray and white checkered coat and a gray fuzzy hat. People parted to let her pass like she’s on the red carpet. We hugged and I told her that I couldn’t believe we finally met in person after spending nearly a year interacting on social media. We shared stories about our life’s experiences, research about pain, and Chinese history and language.

Since that summer of the previous year, Kris had also introduced me to CRPS: complex regional pain syndrome. That topic opened a series of rabbit holes about pain that I had not known about.

Ever since she had a “workplace accident” that damaged a nerve in her right arm in 2001, Kris had fought periods of clinical depression that bonded with sleep deprivation. In June 2017, she wrote that she’d go for months where the insomnia makes her “a little crazy.”

“I’m not the only one, anyone and everyone who goes for long periods of no sleep will eventually go insane,” she wrote. “Actually, I am in a period of insomnia right now, only this time I am in a huge creative flurry of activity, which I believe is much more healthy! Eventually something will click, I will sleep again and life will go on.”

CRPS advocate Kris Leong traveling in London, U.K. in Sept. 2010. (Photo courtesy of Kris Leong)

What is CRPS?

CRPS is a chronic pain condition that often starts at one arm or leg after an injury to the limb, usually involving damage to a peripheral nerve. The pain gradually spreads to the entire body that often renders the person to have difficulty in doing many basic movements, such as walking, eating with a spoon, and typing.

Common symptoms include oedema, changes in the skin’s blood flow, increased skin temperature of the affected limb, and bouts of extreme pain—often at the distal part of the limb like in the hand, fingers, and toes.

For some, CRPS can be as scary as any neurological disease that gradually reduces your ability to control the movements of your limbs. It won’t kill you, make you lose your identity, or your ability to communicate with your loved ones, but it will likely make you shuffle like a walking dead if you can still ambulate.

CRPS gets less attention in health care and the media compared to more common diseases, such as cancer, diabetes, heart disease, and depression. This is likely because CRPS is an uncommon disease that is hard to identify and to diagnose and has a low prevalence among various populations. Although there has been a better understanding of CRPS since the 1940s, there has been little progress in treatment since the end of World War II.

Resources often get funneled toward diseases and other conditions that affect a greater population and geography than those that target a few specific populations. The number of physiotherapists and physicians worldwide who understand the nature of CRPS may be as uncommon as those who understand the biopsychosocial model of pain. And those who had heard of CRPS are even rarer.

There are no universal and consistent descriptions or symptoms of CRPS due to a number of reasons, including definition and identity conflict. The spectrum is so broad that clinicians need to customize treatment for each case, especially when there’s a scarcity of data and good evidence of effective treatments.

What does CRPS feel like?

While how someone’s experience can vary among different people, reports of CRPS symptoms include

- hyperesthesia: too much sensitivity to stimulations, such as heat and touch;

- different temperature sensation and skin color between left and right limbs;

- changes in the skin of the hands and limbs, such as texture, hair, nails;

- asymmetry in sweating between the limbs;

- decreased range of motion and muscle strength and coordination;

- widespread edema, particularly in the limbs;

- joint stiffness and jerky movements of the affected limb.

Among many CRPS patients, they often describe a “burning” or “pins and needles” sensation. Kris is no exception.

“The pain of CRPS is unlike any other. It is an all consuming fire that rages eternally, destroying the best parts of my being and sense of self,” Kris said, who compared the pain with Dies Irae from Mozart Requiem in D and Rachmaninoff’s Prelude in C-sharp minor. “It is locked in a room with someone screaming at you day and night for 20 years so far.”

She described her sensation as an “ice-cold metal being driven into my bones and ripped out again,” her limbed “crushed” from the inside. Her affected arm tends to have more “electric neuropathic pain” than her legs because the spinal cord stimulation implant does not affect it.

“Clothing feels like it is embedded with glass shards as it brushes my skin. Bedsheets and blankets are sometimes too much to tolerate at night, so I often sleep with my legs uncovered, my arm out,” Kris said. “Someone touching my arm, or bumping into me accidentally shoots into my brain like an electric shock.

“This sort of pain is much more difficult to understand and almost impossible to treat. How the body amplifies the pain signals into something that resembles a neverending scream from a child [who] never draws breath and never gets tired.”

What are the stages of CRPS?

In the early 1990s, Dr. John Bonica, one of the founders of IASP (International Association of the Study of Pain), proposed that there are three stages of CRPS:

Stage 1 (acute)

Most people with this early stage of CRPS have edema, erythema (skin reddening), highly warm skin, excessive sweating, and pain that spreads from the site of the nerve injury of the limb. Typical radiography, like X-rays, often do not find an injury or trauma, but bone scintigraphy (using radioactive tracers to get an image of the limb) can often reveal injuries and infections that an X-ray could not. This stage occurs from the time of the injury to three months.

Stage 2 (dystrophic)

Symptoms include severe pain, more obvious skin edema, decreased hair growth on the limb, more persistent sweating, muscle weakness, and limited range of motion of the affected limb and/or other joints near that limb. This stage can happen within the three months after the injury.

Stage 3 (atrophic)

This stage overlaps with stages 1 and 2 where the pain can be disabling starting around week six. There’s further muscle and tendon atrophy and decrease in muscle strength, and the skin of the affected limb can be cold to the touch, dry, and thin. There may be a total loss of joint range of motion and motor control of the limb with symptoms of osteoporosis.

After Bonica died in 1994, his proposal wasn’t challenged until 2002 by a group of researchers, led by Dr. Stephen P. Bruel from Vanderbilt University. They examined 113 patients with CRPS and found that their symptoms and disease progression do not follow in the order as Bonica had suggested.

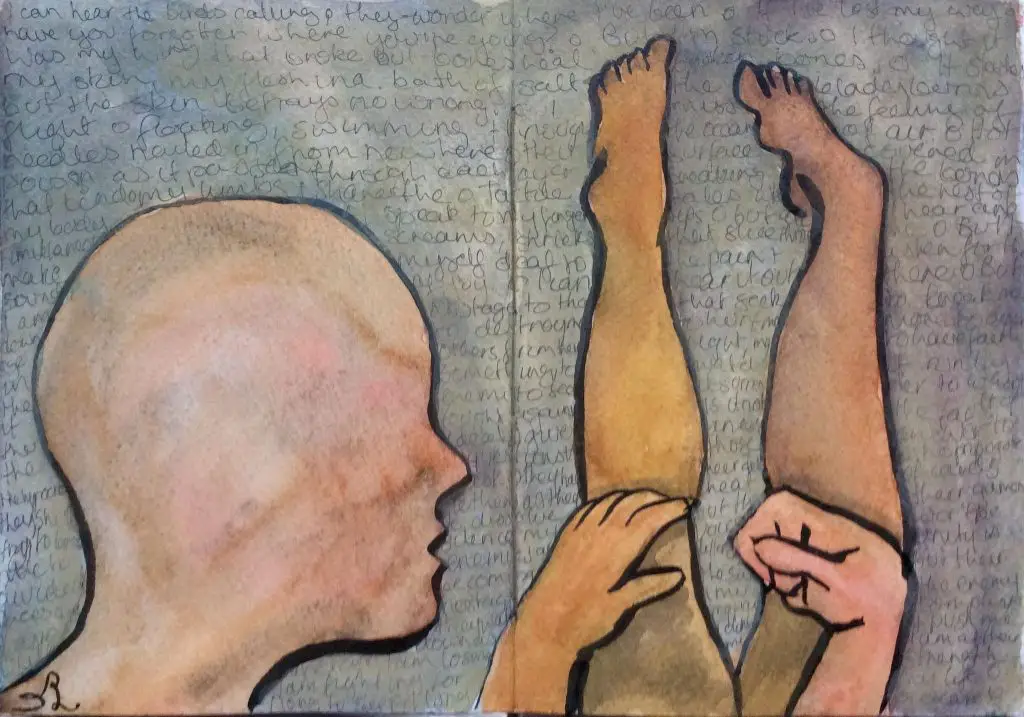

Kris Leong sketched her limbs. (Image courtesy of Kris Leong)

CRPS 1 vs CRPS 2

There are two types of CRPS that clinicians and researchers use to classify the disease.

CRPS 1

Type 1, which used to be called reflex sympathetic dystrophy, refers to the absence of a nerve injury or trauma.

CRPS 2

Type 2 has indications of a nerve injury or trauma.

CRPS-NOS

At the 2003 IASP conference in Budapest, Hungary, another type of CRPS was made, which was called CRPS-NOS (“not otherwise specified”). This type somewhat meets the criteria of the definition of CRPS, but no other explanations can describe close to what the condition is.

How common is CRPS?

Because it’s an uncommon disease, there aren’t a lot of studies that investigate how widespread it is in a particular area or population. One U.S. study in 2003 sampled the prevalence of CRPS in Olmsted County, Minnesota, and the researchers reviewed cases of both CRPS 1 and 2 over a 10-year period.

They found about 6 out of 100,00 people have CRPS, where 5 out of 100,000 had type I and one out of 100,000 have type II. Another study by de Mos et al. found about 26 out of 100,000 people had CRPS in the Netherlands. This included ethnicities and socio-economics that affected the differences as well as having a physician who confirmed the cases of CRPS.

CRPS often affects older adults with women being two to four times more likely to get it than men. Risk factors include menopause, history of migranies, osteoporosis, asthma, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy (ACE). And the major prognosis? Smoking.

Another well-documented risk factor is surgery, especially those of the shoulder (0.9–11%), distal radius (23–39%), carpal tunnel (2–5%), and Dupuytren’s contracture surgery (4.5–10%).

Lower-limb surgery is less studied, but it’s still highly associated with CRPS: tibial tears (31%), intramedullary nailing (33%), nails and screws (28.6%), external fixation (28.6%). However, some researchers acknowledge that some of these reports may have type I error.

A 2012 Dutch study found the following among 596 subjects who had fractures of the upper or lower limbs:

CRPS I: 7.0% incidence, 15% after ankle fracture, 2.9%, fifth toe, 7.9% wrist, 0% scaphoid.

The researchers cited one major problem with this review is that different studies yielded varying ranges (1–37%) and had inconsistent diagnostic criteria. Most of the data are based on CRPS I, which leaves little clues for CRPS II.

But there are some problems with those population studies. In 2019, a group of researchers from the University of California, Davis School of Medicine reviewed these two well-cited studies and found numerous errors in how the research was conducted and reported that may cause clinicians to misdiagnose.

One of the errors is that the symptoms of being short-term bedridden is part of the normal course of an illness, which may or may not be an indication of having CRPS. The current population studies, they wrote, “provide no insight into what types of fracture/sprain events are likely to cause these symptoms…” nor do they classify if these symptoms are part of what is known about CRPS at the time.

They concluded that there are “no clinical protocols established for excluding other medical causes that better explain the [CRPS] symptoms,” nor are there studies that show CRPS can be “reliably distinguished from common conditions such as diabetic neuropathy, postherpetic neuralgia, or psychogenic dystonia.”

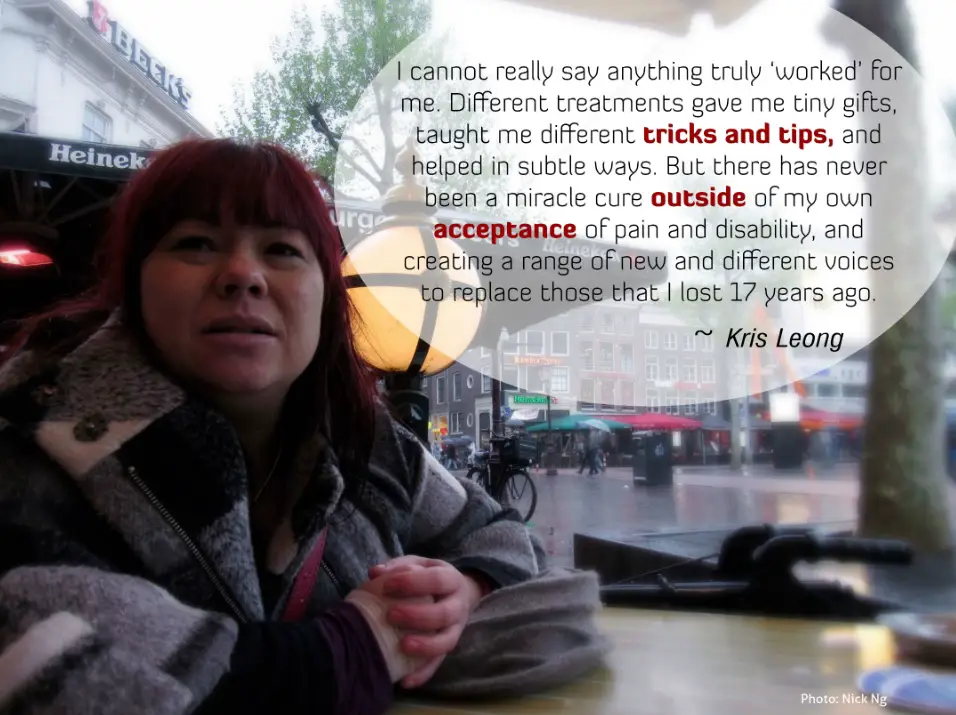

CRPS advocate Kris Leong explains how she feels when someone touches or massages her skin in Amsterdam on April 29, 2018. (Photo by Nick Ng)

CRPS symptoms and causes

Like most types of chronic pain, CRPS doesn’t have one primary cause. Those who have different causes within a wide spectrum can make prognosis and diagnosis difficult. However, the persistent pain seems to sprout from similar sources that other pain sufferers have, such as phantom-limb pain and chronic low back pain.

Inflammation

This usually happens after a nerve injury, which may last for several days or weeks. For unknown reasons, sometimes the symptoms and pain of the peripheral injury is exaggerated and gets centralized in the spinal cord and brain.

In the acute phase, tissue trauma increases the release of various neuropeptides and other proteins that increase blood leakage and vasodilation in the blood vessels. These produce the typical symptoms of acute CPRS.

Altered nerve density

During the acute phase, there’s a decrease of fiber density in the C-type and A-type cutaneous afferent neurons of the affected limb. Such decrease may have something to do with the exaggerated pain. While rat studies find a causal relationship, human trials were unable to replicate the findings.

These findings come from rat studies that show a causal relationship. However, human trials were unable to replicate the findings.

Central and peripheral sensitization

A huge part of the understanding of CRPS and similar types of pain, central and peripheral sensitization are amplifications of pain, which often triggers the inflammation process. This is the body’s way of protecting itself from activities and triggers that may harm and cause further damage.

However, this process can go haywire by prolonging and intensifying pain by the peripheral nociceptors, which can lead to overactive reactions in the secondary nociceptors in the spinal cord. What makes CRPS unique is that this whirlwind of pain can seep into the opposite, healthy limb, which is uncommon among other types of pain.

Altered sympathetic nervous system (SNS) function

When you touch the affected arm of those with CRPS, you would likely find it to feel cool and clammy, and they will likely shoo you away because your touch feels uncomfortable. Because of the vasoconstriction and sweating, these may be driving factors in CRPS progression and keeping the pain “turned on.”

An injury may express adrenergic receptors or nociceptive fibers which would contribute to sympathetic afferent coupling. This chain reaction has been shown to increase pain intensity among patients with SNS-mediated CRPS. They had high SNS activity that increased spontaneous pain by 22 percent, with an increase of spatial extent of dynamic and punctuated hyperalgesia by 42 and 27 percent, respectively.

Circulating catecholamines

Tying with altered SNS function, the CRPS-affected limb has a drop in plasma norepinephrine, a hormone that helps send signals between neurons. So, there’s an upregulation of peripheral adrenergic receptors, which leads to supersensitivity to catecholamines, which are a class of neurotransmitters that the adrenal glands produce for “fight or flight” response. The outcome is the cold, clammy feeling of the affected limb.

Auto-immunity immunoglobulin G (IgG)

Of course, we cannot rule out the contributions of our immune system to CRPS progression. In blood tests of CRPS patients in one study, there’s an increase of the number of IgG auto-antibodies that attach themselves to antigens on autonomic neurons in the blood.

These patients were given intravenous IgG treatments that decreased their pain significantly when compared with patients who were given a placebo. However, larger randomized controlled trials found no benefits.

It seems like a hit-or-miss among different patients, and small-sample studies tend to fall under the small sample fallacy where such studies (usually below 100 subjects) tend to exaggerate positive or negative results.

Brain plasticity

The brain also changes in how it “maps” the affected limb. In brain imaging studies, there’s a decrease in the area representing the CRPS limb in the somatosensory cortex compared to the unaffected limb. This has been shown to correlate with pain intensity and hyperalgesia.

Genetics

If you have brothers or sisters and you have CRPS—assuming you’re under age 50—they’re three times more likely to develop CRPS than if you don’t have it.Because of mitochondrial inheritance (where genes in the mitochondria are inherited from mom to you), these genes that encode HLA strongly correlate to CRPS development.

Psychology

A classic “chicken or the egg” problem where researchers have not yet determined if CRPS causes clinical depression and anxiety or vice versa. If you already are prone to depression and anxiety, CRPS may likely amplify the conditions.

What’s the best treatment for CRPS?

Because of the wide variations and complexity of CRPS, there’s no “best” treatment for it nor is there a “recipe.” What works for Kris may not work for another, even if they have carbon copy life experiences and biology.

Spinal cord stimulation (SCS) involves a surgical insertion of an electrical device at the spine where the pain originates. The device emits electrical signals to the spinal nerves to reduce the pain.

A 2016 Cochrane Review by physiotherapist Keith Smart and his colleagues from St. Vincent’s University Hospital in Dublin, Ireland, reviewed 18 qualified randomized-controlled trials (RCTs) with 739 patients with only CRPS I.

Among the treatments reviewed—including graded motor imagery, mirror therapy, electrotherapies, massage therapy—there was very little good evidence that demonstrated any of them are clinically significant better than a control group or another intervention.

Even one study that compared physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and “usual care” (medical management with social work) was rated as having a high risk of bias because the researchers “did not adequately report details regarding the nature of the interventions and did not standardize the number of treatment sessions given,” such as the frequency, duration, and intensity of the treatments.

Although physiotherapy was “statistically significant” in reducing CRPS disability compared to social work (but not occupational therapy), there were not much differences among the groups one year after treatment.

CRPS advocate Kris Leong’s spinal cord stimulation implant (SCS) during a trial in the Netherlands. (Image courtesy of Kris Leong)

Smart et al. did this Cochrane Review because previous systematic reviews on physiotherapy and CRPS included low-quality trials, such as case series and non-RCTs, and excluded non-English studies. Previous reviews also didn’t include a quality-control system called GRADE, which evaluates the strength of the evidence. They also pointed out some factors that clinicians should consider:

- Some trials are based on military populations so context and outcome may likely be different if they were from civilian populations.

- Most trials did not report adverse effects so we don’t know what risks are there for which populations. Only 2 out of 18 trials reported them.

- Publication bias: Nearly 25 percent of published studies did not report on the type of pain intensity measurement the researchers used.

- Lack of statistical power could increase the risk of getting false negatives.

- Low clinical equipoise: Researchers in the study may favor one particular modality over another.

Despite the lack of strong evidence of the effectiveness of CRPS treatments, clinicians can still apply the basic principles of pain science with their CRPS patients.

Dr. Robert Johnson, who is a practicing physiotherapist at Achieve Orthopedic Rehab Institute in Chicago, Ill., suggested in a phone interview that clinicians should not shy away from treating the peripheral nerves because it’s possible that peripheral sensitization could lead to central sensitization.

“[Professor] Lorimer Moseley had established a foundation on how we treat CRPS patients, based on the top-down model,” Johnson explained. “For example, in one study, he found that the amount of pain one has can influence how risky you are in developing centralized changes in the future after an acute injury.”

Imagery is huge in Johnson’s practice, and it’s an important piece of the CRPS puzzle. When patients lose their perception of what a “normal” limb is supposed to feel like, something changes in the brain, a distortion that is likely to contribute to chronic pain.

“They tend to forget what it used to feel like, like walking on the beach with sand on their toes, holding someone’s hand. It takes time to recapture,” Johnson said. “That’s what imagery is supposed to do. However, sometimes their ‘top-down’ has a hard time to imagine that.”

It’s a slow process for many of his patients, and Johnson combines imagery with education, listening, and movement.

“This is all central processing, not so much with the limb itself,” he said. “If they can’t capture that, maybe it’s the brain’s inability to sense what it used to feel like.”

CRPS advocate Kris Leong talks about her experience with treatment in Amsterdam on April 29, 2018. (Photo by Nick Ng)

Applying CRPS research to clinical practice

Although the Cochrane Review may seem like a dampener for physiotherapists and massage therapists, there are some good takeaways we can learn and apply from the review.

Janet Holly, who is a physiotherapist practicing in Toronto, Ontario, and is a member of the International Research Consortium for CRPS, told me in an online interview that the Cochrane Review is not really up to date. She said that it includes early trials that had “mixed diagnostic criteria” when the definition of CRPS and understanding of it were still unclear. These early trials mixed chronic and acute CRPS diagnosis. Holly emphasized that clinicians should consider the statistical change in outcome measures of the trials.

“Outcome measures commonly target impairments versus quality of life and participation measures,” Holly said. “Oftentimes, treatments can have a significant impact on higher level function and life satisfaction with limited statistical changes in range of motion or strength. As such, future trials need to focus on outcomes that measure both top-down and bottom-up treatment approaches in order to determine the true successfulness of a trial for a patient. The COMPACT outcome measures are specifically designed to do this.”

Some studies with a high PEDro score of 8—on a scale of 0 to 8—were also “contaminated” by the experimental group and the nocebo effect in the control group, which can affect the studies’ outcome.

Another factor that Holly and Dr. Tara Packham elaborated, who is her coauthor of a recent paper that covers CRPS management, where they emphasized that CRPS care must be individualized rather than a cookie-cutter approach. Their review also found limitations in early CRPS studies, such small sample sizes and mixed experimental methods that may skew the results.

“Clinicians up to now have been using a ‘throw spaghetti at a wall and see if it sticks’ approach to rehabilitation,” Holly said. “My co-author and I recommended a more reflective approach to treatment and linking the evidence to the presenting signs and symptoms of the patient and identifying which of the eight predominant mechanisms exist.”

She cited Dr. Stephen Bruehl of Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn., who presented data in 2015 that demonstrated three key subgroups that could be found among CRPS patients, each with its own predominant signs and symptoms.

“This supports the need to fully assess and consider the mechanistic presentation of the patient in front of the clinician,” Holly said. “This is further supported by Lageux et al., 2018 and Rome et al., 2016 who insisted on individualized treatments.”

Some patients have difficulty in doing some of the exercises prescribed by their physiotherapist. Holly provided a few strategies among many that can make them more adherent to the exercises.

“A mother of young children can use the graded motor imagery cards and play the game of concentration with her children,” Holly suggested. “What is a homework activity can also be a play activity with children. Or when we begin graded activities making cookie dough and baking it on another day can be activities to be engaged in with children. Restoring the roles of mother, spouse, friend, employee, church member, etc. is important.”

At the surgical table from the patient’s perspective. (Image courtesy of Kris Leong)

When confronting research that sometimes shows conflicting information of how well treatments work, Holly highlighted that evidence-based practice isn’t just the application of research, but rather “the application of research in the context of the patient you are treating.”

“Where evidence does not exist, a competent clinician must fall back on basic science principles of anatomy and physiology for the condition in front of them,” Holly said. “Therefore, although the systematic reviews are not showing a propensity of high-level evidence, a critically reflective clinician must weigh what evidence exists in light of their patient.”

Clinicians like Holly and Johnson may find working on CRPS cases with other healthcare professionals to be borderline frustrating. From Holly’s experience, some can be impatient and expect immediate recovery after a treatment. Some are limited to their narrow focus of practice which ignores other factors that contribute to CRPS, which can miss the bigger picture of chronic pain.

For example, some physical therapists and chiropractors might emphasize isometric exercises or using passive treatments that make patients rely more on their care. And some massage therapists might use aggressive techniques that may inflict more pain to patients who are already in pain.

“When we do not have an intact body schema, function will not improve. We need to re-establish body schema map representations. These timelines are not measured in the length of time it takes a bone or soft tissue to heal,” Holly said.

Some chronic pain patients grieve because they can no longer do some things they once enjoyed. Holly said that this is a part of the normal process of healing that has no time limits and cannot be rushed.

“Patients can become stuck in the grieving cycle and rehabilitation clinicians will make little progress until a psychologist can assist with facilitating the continuance of the grieving process,” she said. “Rushing and pushing the patient only increases anxiety, which will ramp up pain creating a cascade effect into deteriorating status.”

“Grief is different. Grief has no distance. Grief comes in waves, paroxysms, sudden apprehensions that weaken the knees and blind the eyes and obliterate the dailiness of life.” ~ Joan Didion, “The Year of Magical Thinking”

How do you explain CRPS to family members?

While this is difficult to answer, Kris suggested that CRPS needs to be explained with “some sensitivity” because it’s possible that the sufferer may interpret certain comments as negative, which may continue their cycle of “doom and gloom.”

“Being frequently asked how the pain is, does it hurt, and so on; [it] all gets a bit annoying. Most of the time an honest answer isn’t what the person wants to hear, so they get a lie,” Kris said. “That deception feeds into the isolation and distress already being felt, feeling that they do not have permission to admit to others the truth of how things are for them—their reality.”

Kris also advises that having sympathy, empathy, or pity can be “diminishing” to those in pain because it makes them feel responsible for the other party’s suffering.

“It’s normal to feel some of these emotions, to feel bad for someone who is experiencing something terrible,” she said. “But it is also unfair to make them carry your emotional baggage as well as their own. Compassion and solidarity do much more good than sympathy or empathy.”

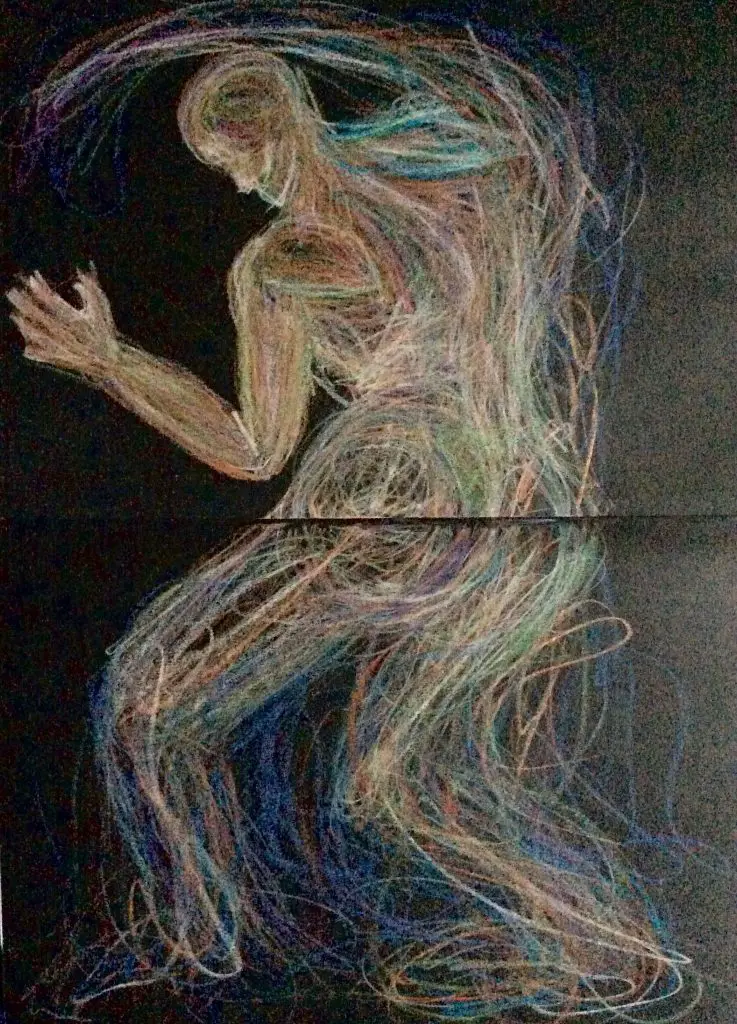

Kris Leong’s representation of her own nervous system. (Image courtesy of Kris Leong)

Perhaps one of the biggest things, but not always the easiest, that therapists can do for their patients is listening to their stories and understanding where they’re coming from.

In addition to exercise and sketching, Kris said that understanding the BPS framework of pain and overall health have a huge help in coping and accepting her condition.

“[It] gave me the knowledge to understand and frame my own pain experience. It also allowed me to let go of the fears of causing more damage, and enabled me to take greater risks in treatment and activity,” Kris said. “I could tolerate pain in the knowledge that I was not damaging anything. It became a question of worth or value: was this activity worth the price of an increase in pain? Was I gaining something of longer-term value?

Kris said that cost-benefit analysis is also useful in deciding if an activity is necessary and suitable for her nor not.

“The problem was in a work environment: how much more pain was I expected to endure, for an unsuitable job that was unwilling to make allowances? The additional stress in these jobs made it far worse to endure,” she said. “There were jobs out there, I discovered later. But being limited by workers compensation or other insurance systems meant that these jobs were few and far between.

“I was able to take stock of my own emotions and how they impacted my overall pain experience,” Kris continued. “It was a way to become the driver of my own destiny rather than a victim of circumstance. There were many stumbles along the way, many failures and losses. However, I never would’ve gotten anywhere or achieved so much had I not been given such a powerful toolbox in those vital, early years.”

CRPS advocate Kris Leong depicts the warm glow in the sky during the 2019-2020 Australian bushfires. (Image courtesy of Kris Leong)

Having a creative outlet, such as sketching people and cityscapes of Amsterdam, helped her cope, a way for her to express that pain wasn’t the dominant force that controlled her life.

“Though it didn’t completely solve the pain problem, it gave me the strength and courage to face it head on,” Kris said. “Living with hope is a double-edged sword. Having hope can be wonderful, but it can also be incredibly devastating. Instead of searching for cures that don’t exist, it is better to search for things that can improve overall quality of life or improve isolated symptoms. Going into treatment hoping to be cured all the time means that smaller but important improvement successes are overlooked and seen as failures.

Like most other types of chronic pain, pain is a part of life, an “unwanted and always present companion,” Kris described. “It doesn’t need more attention than is necessary.”

“Patient autonomy is very important,” she continued. “Pain is something that is completely out of control, nothing I did or didn’t do made any difference. But having some autonomy, some control about my existence meant that I was more willing to submit myself to something that may be unpleasant. In CRPS, there are a lot of unpleasant things in treatment, it is always better if you can feel some degree of control going into it.”

Sketches of jazz musicians in Amsterdam in 2017. (Image courtesy of Kris Leong)

(This story was originally published in the Summer 2018 issue of Massage & Fitness Magazine. Updated for 2022.)

A native of San Diego for nearly 40 years, Nick Ng is an editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine, an online publication for manual therapists and the public who want to explore the science behind touch, pain, and exercise, and how to apply that in their hands-on practice or daily lives.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a B.A. in Graphic Communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014.

When he is not writing or reading, you would likely find him weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, or exploring new areas to walk and eat around Southern California.