In the fall of 1990 when I was in eighth grade, my family moved further north in San Diego County, away from Mira Mesa where I had lived since first grade. Before we moved, many questions and uncertainties swirled in my brain with hundreds of “what ifs.”

What if I don’t like the kids and teachers at the new school? What if they don’t like me? What if I need to retake some classes?

And more importantly: how do I keep in touch with my old friends? (This was way before smartphones were commonplace.)

That anxiety I had since my childhood didn’t dissipate as I got older. I carried it in the past 20-plus years, getting that tingle and throbbing pain in my lower back, neck, and temples whenever I was about to move to a new place.

The author in 8th grade at Wagenheim Middle School (San Diego, Calif.) in Oct. 1990, weeks before he and his family moved further north in the county. (Photo by Nick Ng.)

And so, our pain experience and environment are inseparable like milk and espresso in a cappuccino. As neuroscientist Dr. Robert Sapolsky mentioned in a 2018 conference, “We’ll get nowhere if we look for one part of the brain, or one gene, or one childhood experience” to pinpoint why some people behave the way they do.

He emphasized that we should look at behaviors on a time scale—from the seconds, minutes, and hours that led to the behavior to the person’s childhood, family, and culture that shaped their experiences and behaviors.

Chronic childhood anxiety is one condition among many that are highly influenced by environmental factors.

This holistic view doesn’t negate the importance of our biology’s influence on pain and anxiety; it just gives our “bio” better context of why it happens.

And anxiety itself isn’t bad. It’s part of our normal, survival behavior that we need to respond to threat or a perception of threat.

For example, we’d get anxious when we see an approaching bear or a police car flashing its lights behind you. But our anxiety diminishes when we see the bear walk away or the cop gave you a warning and didn’t issue a speeding ticket.

But chronic anxiety manifests when there’s no actual threat. You tense and freeze every time you hear something scampering in the bushes near you, even if it’s just a squirrel or rabbit. You sweat and your heart races every time you see a police car on the road.

What are the signs of childhood anxiety?

Signs of childhood anxiety are quite universal among different cultures and populations, even though different types of childhood anxiety have different symptoms and environmental context.

General anxiety disorder

In general anxiety disorder, children might not be able to turn down their “danger signals” in their brain. They’re constantly worried about the future and daily events, such as grades, bullying in school, and sports performance—or in more recent times, school shootings.

Panic attacks

Symptoms of panic attacks include elevated heart rate and sweating, shortness of breath, trembling, dizziness, tingling or lack of sensation in the limbs, and fear of losing control of things.

Panic attacks aren’t triggered by any specific stimulus; instead, they can manifest spontaneously and can vary among each person.

Social anxiety

Social anxiety is the excessive fear of socializing with other people, whether it’s having a conversation, eating or reading at school while thinking they’re being watched, or rehearsing at a school play.

Sometimes social anxiety can be confused with the typical behavior that most children have, such as avoiding an interaction with strangers.

Separation anxiety

Separation anxiety is when a child has an extreme attachment to their parent or caregiver. They would refuse or be reluctant to go to school or anywhere without the adult.

They may have fears of being kidnapped or abandoned, or have a fear of the death or disappearance of the parent/caregiver.

Phobias

Some children have an inherent fear of certain things, like dogs, snakes, thunder, and airplanes, but they don’t overcome these fears as they get older.

Some phobias may be mundane to most people, such as strangers in a department store, snails, and blue socks, but the sight of them can amplify the symptoms of the children’s anxiety.

Chronic anxiety in children can cause them to be constantly alert, even if the environment lacks inherent danger to them. (Photo by cottonbro.)

Childhood anxiety checklist

Because anxiety often overlaps with other mental health issues, such as depression and various types of trauma, it may be challenging for clinicians to identify whether their young patients have anxiety.

“Working with kids, sometimes they’ll already have a diagnosis of anxiety and may be using therapeutic services or medication management to help with anxiety,” said Dr. Abby Gordon, who is a physical therapist at Seattle Children’s North Clinic in Everett, Wash., and the Team Physical Therapist for the Seattle Storm. “But we frequently see kids who haven’t yet had a diagnosis and have some signs of anxiety that might interfere with rehab.”

Gordon described several common signs that she had seen in her career of working with children and teens:

- The child looks to their parent to answer questions for them or is frozen and unable to speak on their own behalf. Sometimes they’re “squirmy” and just look uncomfortable.

- The parent jumps in and answers questions on behalf of their kids, especially if questions are directed to the kid.

- The child cries when being asked to do a movement or action that most other kids wouldn’t cry about.

“For example, an anxious kid might cry when asked to move their wrist after it has been taken out of a cast because they think it might hurt,” Gordon said. “A non-anxious kid recently out of a cast might try to move slowly to see if it hurts and respond to the movement. If they take anxiety medications or have a therapist to help with coping strategies so anxiety is more tolerable, that should be noted.”

Dr. Amanda Rixey, who practices at Newfound Physical Therapy in Seattle, Wash., suggests that clinicians should rule out red flags where pain isn’t muscle or joints in nature. “This includes a thorough review of systems with specific testing as needed for screenings, including neurological or cardiovascular findings,” Rixey said. “Positive findings would warrant referral to physician specialists for further examination.

Rixey also highlighted that therapists should consider:

- “Yellow flags” that are more psychosocial in nature that comes with musculoskeletal pain, such as fear avoidance behaviors to specific movements;

- screening for anxiety and depression;

- low physical activity level;

- reported loss in functional mobility, strength, and/or balance;

- identifying the patient’s coping strategies for pain;

- identifying the patient’s specific movement and activity goals.

“When working with all patients, one must consider adapting communication styles in order to work with the patient. Specifically with children, it is about figuring out how to communicate with each individual,” Rixey said. “Working with the pediatric population means you technically have to communicate with both the caregiver/adult and the pediatric patient. You can’t simply communicate with one or the other, the message must be relayed to both. Age is not a reason the plan of care, specific interventions, etc. cannot be explained—it simply must just be tailored to the target audience.”

Risk factors of childhood anxiety

Current research finds that gender, age, educational level, socioeconomic level, and parenting styles are moderate to high predictors of developing various types of anxiety disorder, but each factor has its own nuances.

Gender and age

While early research finds that girls are twice as likely to develop anxiety disorders than boys at about age 6, there’s not much difference during infancy and early childhood. However, as children age, the difference begins to widen.

Also, female teenagers are more likely to develop anxiety disorders and depression if they also have anxious parents (e.g. economic hardships, lack of personal safety) than male teens, according to a 2021 longitudinal study.

Socioeconomics and education

Current research suggests that the socioeconomic status and education level of the child and their family are strong predictors of developing childhood anxiety.

A 2019 German study of more than 2,100 children and their families found that those who have lower income, education level, and higher worries of financial stress are more likely to develop mental health problems later in life.

The researchers stated that “mental health problems at baseline were the best predictor for mental health problems two years later.” This can be a merry-go-round of suffering that doesn’t seem to have a cause or an end.

Interestingly, in a Japanese study of 1,682 people found that children of parents with a high school education level or higher were about 5.5 times to 8.5 times more likely to get general anxiety disorder than those who didn’t finish high school.

While the researchers found that women in this sample were more likely than men to get depression, men were more likely than women to get anxiety.

But whether you’re richer or poorer, parents’ anxiety and poor coping behaviors can pass their stress onto their children, which is a strong predictor of children developing chronic pain and mental health problems.

Parenting styles

Authoritarian parenting style tends to emphasize less nurturing and responsiveness from children while demanding more obedience and providing less elbow room for children to make their own decisions.

Compared to authoritative parenting, which is quite the opposite from authoritarian parenting—but still emphasizes high standards from their children and punishes misbehaviors—research finds that children of such parenting are less likely to develop anxiety disorders.

However, too much coddling or rejection behavior can also increase the risk of anxiety disorders, particularly separation anxiety.

Abuse

It’s no surprise that child abuse of any kind can be an overwhelming factor in causing childhood anxiety and chronic pain, which increases the risk of carrying them into adulthood.

Most of the scientific evidence points to strong correlation between childhood trauma (including abuse) with the risk of getting anxiety and depression later in life.

For example, an international team of researchers reviewed 19 studies with a total of more than 115,500 people from different countries and cultures.

They reported that their estimations “suggest at least a doubled [odds ratio] for depression or anxiety related to sexual abuse” and slightly lower for physical abuse. In other words, adults who had experienced child abuse are twice as likely to get depression or anxiety than those who didn’t experience such abuse.

Physical therapists in the U.S. are obligated to report to Child Protective Services or a social worker if they suspect their patient is a victim of abuse.

“Child Protective Services manages cases once they are reported, and it is appropriate to report if you are suspicious of abuse,” Gordon said. “Consider that if you don’t report it, potentially nobody else will, and there will be no investigation to provide safety for the child.”

She doesn’t advise therapists to confront the family because it might not get the child the help they need. “If a child appears to be in imminent harm, a 911 call would be indicated,” Gordon said.

Childhood anxiety and the brain

The brain is the center from which anxiety and other mental health problems process, but it’s the environment that shapes how it develops.

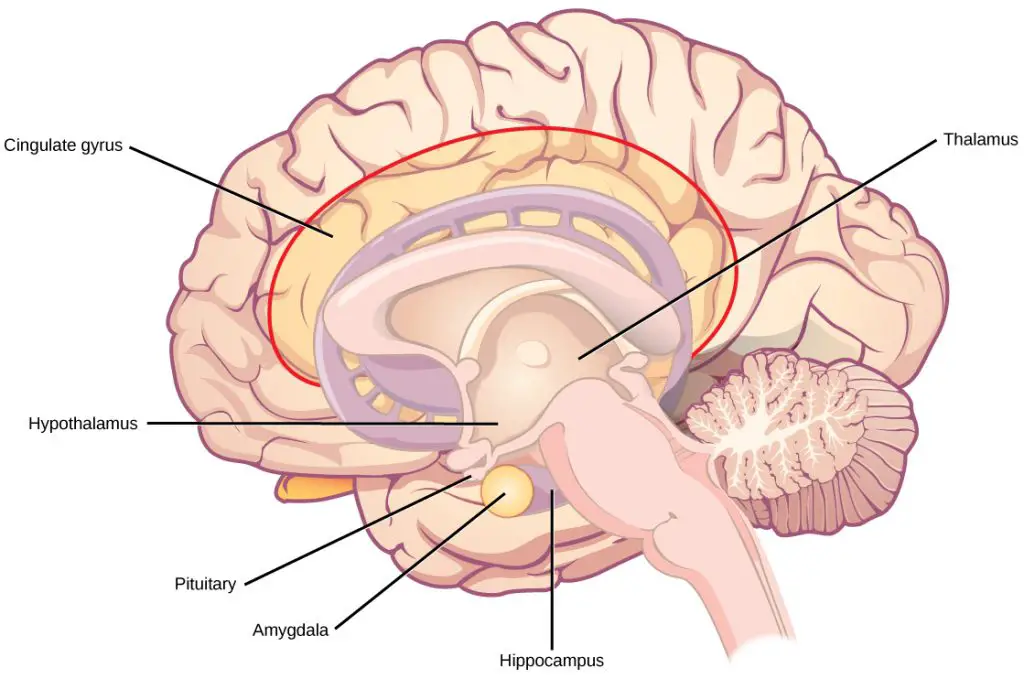

During infancy, the brain stem is developed first, the part that maintains the functions that we sometimes take for granted, like heartbeat, breathing, and digestion. Other parts of the brain that perform higher functions, like the hypothalamus and cerebral cortex, are still developing but at different rates than the brain stem.

How we regulate our thoughts and emotions evolves further during childhood and early adolescence in the prefrontal cortex, which handles abstract cognition (e.g. geometry, thinking about thinking, logic puzzles) and emotional regulation (e.g. delayed gratification).

(Illustration by CNX OpenStax, distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.)

This area doesn’t get fully developed until around mid-twenties and requires our neurons to grow and branch out to each other, forming billions of networks that help us perceive our world, interact with people, and develop basic motor skills.

For this to happen, however, it requires a proper amount of environmental stimulation and timing during children’s development.

Compared with children who had never experienced abuse or other types of trauma, abused children have a much higher risk of:

- delayed language and motor skill development;

- higher impulse and hyperactivity;

- social anxiety and avoidance.

One such stimulation is physical touch. If they don’t get this much or at all—even if they have enough food, water, and shelter—there’s little reason for their developing brain to form enough connections.

We can see the results of such abuse in one infamous example among hundreds of thousands of Romanian orphans in the 1980s who were living in institutions. They lived and slept in crowded rooms and were never coddled or cared for—other than given water-down gruel fed in bottles even for those as old as seven.

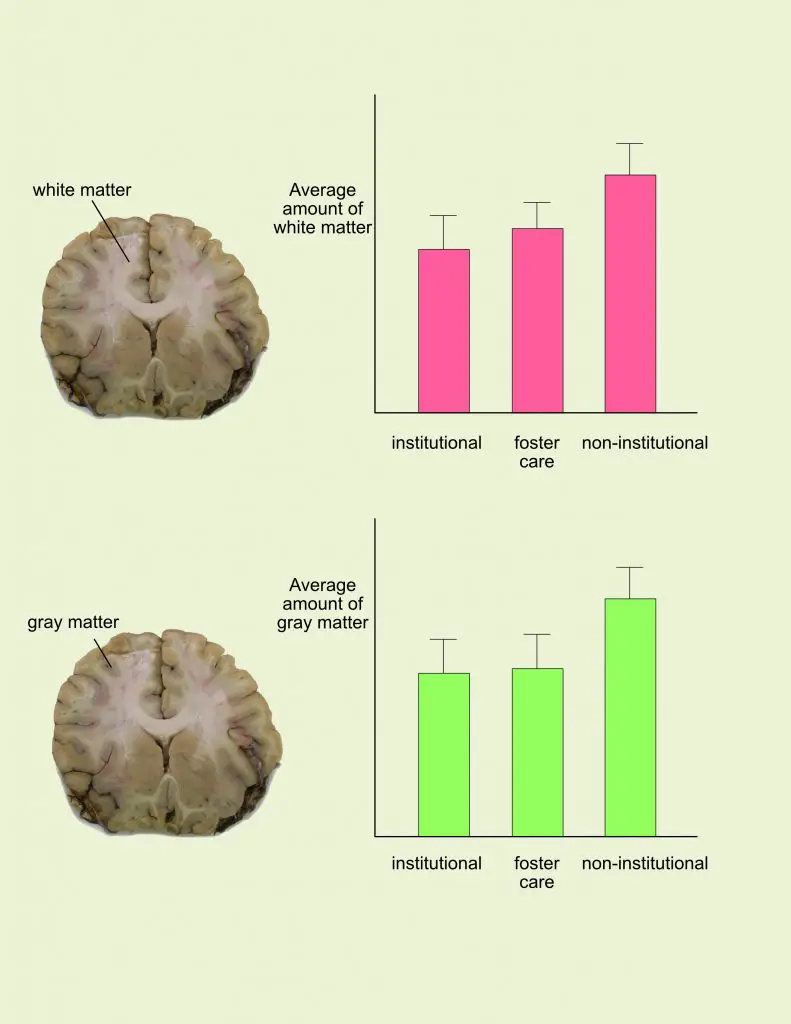

Research has found that orphans tend to have lower cognitive, emotive, and motor skill development than non-orphans. These kids tend to have smaller brains and lower volumes of white matter (nerve fibers that send signals to neurons) and gray matter (neurons’ cell bodies, dendrites, and axons).

However, those who were adopted earlier in their life are less likely to show such developmental delays than those who remained in an institution longer.

Still, when the kids who went to foster homes were compared with those who were never institutionalized, the former still had lower volumes of gray matter even though their white matter had increased.

Comparison of white matter and gray matter in the cortical area among institutionalized, fostered, and non-institutionalized children. (Image by Nick Ng. Data adapted from Bick and Nelson, 2015)

“If this is absent for the first three years of life and then a child is adopted and begins to receive attention, love and nurturing, these positive experiences may not be sufficient to overcome the malorganization of the neural systems mediating socio-emotional functioning,” Dr. Bruce Perry wrote, who is the senior fellow of Child Trauma Academy in Houston, Texas, and the author of “What Happened to You?”

That’s because some of the chemical signals in the brain must be developed during a timeframe of the infant’s life. The lack of proper development “may lead to major abnormalities or deficits in neurodevelopment,” Perry wrote.

In our brain, the limbic structures regulate our stress response—specifically, the amygdala, which acts as a threat detector.

How much the amygdala activates depends on the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPC), which keeps it “under control.”

When we fail to sense safety in our environment, the VMPC activity decreases, which allows the amygdala to run wild with fear. The threat is gone yet your eyes dart around, your arm muscles tense.

It may take much longer—sometimes never—for chronically anxious people to register safety.

However, we should not equate “lack of threat” with “lack of safety.”

Psychologists Jos Brosschot, Bart Verkuil, and Julian Thayer emphasized that we must learn to know “where and when life is safe, and thus, to learn where and when to find safe periods/safety zones—in other words what the ‘contextual’ [stimulus] exactly is.”

They believe that anxiety needs a new theoretical model—named Generalized Unsafety Theory of Stress (GUTS)—which combines neurobiology with evolutionary biology.

This includes the idea that anxiety causes someone to be unable to recognize safety signals and develop a distressful response, like thumb twirling, fingernail biting, and hyperventilation. They proposed that anxiety isn’t so much about worrying whether there’s a threat or not, but an uncertainty of safety.

For some reason, these children and teens are unable to perceive “neutral” environments, such as a shopping center or a local park, as a cue to safety when there are no signs of threat whatsoever. From an evolutionary perspective, this behavior is a key to survival.

“[Generalized unsafety] causes the default stress response to remain activated, whenever our phylogenetically ancient mind-body organism fails to perceive safety in a wide range of situations in modern western society that are not intrinsically dangerous,” Brosschot et al. wrote. “Chronic anxiety is just one of the conditions in which the default response remains activated.”

Communicating with children about anxiety and pain

Rixey emphasizes that therapists should put themselves in their young patient’s shoes when they talk to them about their pain.

“Find a way to connect to the patient, grab their attention in order for them to trust you and be interested, and then you can relay your message,” she said. “Often, it’s a matter of experimenting with verbiage because one patient will hear something a different way than another patient, regardless of age.”

One challenge Rixey often faces is explaining the science behind pain to her young patients, yet it’s a “crucial” part of physical therapy to help them understand about their body.

“There is a large level of creativity involving storytelling, analogies, imagery that often help getting the point across,” Rixey said. “Being able to experiment and feel confident in doing so and feeling comfortable enough to try multiple ways of getting the message across is important. Also understanding that small messages are better interpreted than a large amount of information, so being patient with each patient is necessary. This often will take multiple sessions to get one message across.”

Among the many tools of manual therapy, Gordon believes that having a therapeutic alliance is paramount when working with children and teens. This involves the relationship between the therapist and the patient that influences the patient’s outcome.

“At the end of the day, I think we need to acknowledge the presence of anxiety and embrace each individual for their baseline level of arousal because the healthcare system could probably help reduce anxiety if we prepared patients better for their upcoming procedures and educated the masses more about pain,” Gordon said. “Pain, though uncomfortable, is important to our survival and necessary to protect human function.”

A native of San Diego for nearly 40 years, Nick Ng is an editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine, an online publication for manual therapists and the public who want to explore the science behind touch, pain, and exercise, and how to apply that in their hands-on practice or daily lives.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a B.A. in Graphic Communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014.

When he is not writing or reading, you would likely find him weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, or exploring new areas to walk and eat around Southern California.