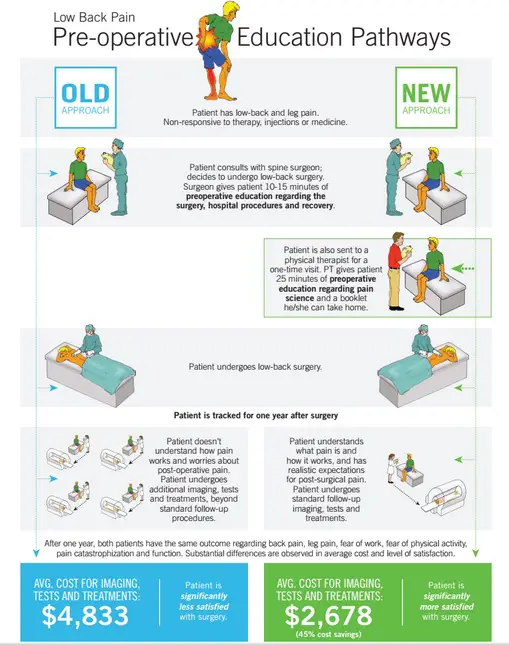

Last year, an American study published in Spine — led by Dr. Adriaan Louw from the International Spine and Pain Institute — showed that patients who received pain education with a physical therapist before they undergo lumbar radiculopathy surgery had better expectations and recovery than those who received no such education.(1) Patients who were eligible for the study were randomly assigned to an experimental group that included pain education with the standard consultation with their surgeon and a control group that received no pain education. All patients filled out surveys that measure their satisfaction, beliefs, and outcomes of the procedure. They were followed up in 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after the surgery in regards to their leg pain, low back pain, and disability.

While the pain education group had lower pain scores than the non-educated group during the 1-, 3-, 6-, and 9-month follow-ups, both groups scored almost the same after a year post-op — except for the leg pain score where the educated group scored higher. However, the cost of tests, treatments, and follow-ups in the pain education group is about 45 percent less — about $2,600 on average in savings per patient — than the non-educated group. The former group had less imaging and diagnostic tests and less visits to their physician, physical therapist, and/or chiropractor.

A previous study by Morris et al. that was also published in Spine also examined whether if patient education about pain can affect outcomes of spine surgery. (2) However, the content of the education is quite different. While the Morris pain education package is mostly based on anatomy, biomechanics, and pathology (based on the biomedical model), Louw’s pain education focuses on neurobiology and neurophysiology.

“If patients in the NE group in our trial did indeed view their pain and disability as being less about persistent tissue pathology and more about persistent nerve sensitivity, it may account for the observed decrease in health care utilization after their surgery,” Louw et al. wrote. (1)

Limitations and Considerations

Like almost all research, there are potential limitations that could affect the study’s results and outcome. First, the sample population only has lumbar radiculopathy and may not extrapolate to other types of lower back pain or pain in other body parts. The pain education itself was delivered in a single session without any future reinforcement to see if each patient had retained any of the information he or she had learned. (1) Also, there was no control of frequency, duration, and type of therapy the patients sought after their surgery.

However, Dr. Louw has further prospects for this study. “We published our data following one-year follow up. We are actually in the process of preparing for publication the three-year data,” Louw explained in an online interview with Massage & Fitness Magazine. “We tracked the patients three-years out (novel/uncommon in rehabilitation) and although we’re still working all the stats out, it seems our one-year findings get even better. At one-year post-surgery patients who received preop pain education spent 45 percent less on healthcare and had a superior surgical experience. Both of these extend to three years and seem to get even better. For example, healthcare savings are over 50 percent compared to people who did not get pain neuroscience education.”

Louw and his team went back to the patients who had received pre-op pain education and analyzed which pain messages or stories help them the most. Currently these new findings have been submitted and accepted in the European Spine Journal, according to Louw.

Why Was This Study Done?

“First and foremost, I personally was surrounded by some of the leading thinkers in this regard for the past 15 years (Gifford, Butler and Moseley) who heavily influenced my thinking,” Louw lauded. “Over time I became increasingly aware that any injury or tissue issue in high-anxiety states (i.e., trauma, surgery, war) lead to increased rates of persistent pain and disability. Clinically, I worked with a plethora of postoperative spine surgery patients and felt that by the time we saw them a lot of issues were entrenched. For my Master’s degree we designed a study where I interviewed patients after surgery to find out about their surgical experience and, along with other studies, found out they had poor beliefs, scared to death, and got very little information. At the same time early research showed that in other complex spine patients (chronic back pain), [pain education] was able to produce significant meaningful changes. We then devised (for my PhD) a series of questions we had to try and answer, culminating in the present study we published:

1. What do lumbar surgery lumbar surgery (LS) patients want?

2. What constitutes “usual” preoperative LS education?

3. What does the general population think about LS?

4. Is there any effective preoperative strategy that can be borrowed?

5. Is there any other effective strategy that can be borrowed for complex back patients?

6. What happens when a “surgical” brain understands more?

7. Can we develop a LS program using all of this information?

8. Does such a LS program produce superior results?

“Out of this we wanted to see if we developed a pain-specific pain education program if we could change post-surgical patient’s lives for the better.”

Spine surgery in the US is five times the rates of the UK and twice that of Canada, Australia and the Scandinavian countries, according to Louw. “One in three people after lumbar surgery have the same or more pain and disability than before surgery. Postoperative rehabilitation has some efficacy but patients are often not referred to physical therapy. The surgical experience and pain cause increased fear and anxiety.”

Can Massage Therapists Apply This Into Their Practice?

“Yes. All healthcare providers can learn pain neuroscience and share that with their patient,” Louw explained. “Pain neuroscience education’s key tenant is to take the complex pain material and get it on a level that they get it. You do have to, however, be ‘smarter than their patient’ so [therapists] need to study, learn, and know the material well. Remember, a little knowledge can be dangerous. We are now studying all kinds of parameters on ‘learning about pain’ and spreading it to parents, caregivers, kids, the elderly, etc.

“Pain education alone is helpful, but not as much when combined with movement and touch. In all the studies we analyzed, the pain education sessions that added some form of movement or touch had far superior outcomes in regards to pain relief versus pain education alone. So? Pain science is hands-on, not hands-off, which is good news for those using their hands.”

Armed with the principles of modern pain explanation, massage therapists can also contribute to patients’ or clients’ pain relief in addition to their hands-on work. While we may not need to go into too much details in neuroscience, how we communicate the information to the person lying on the table can affect the quality of our hands-on work.

References

1. Louw A, Diener I, Landers MR, Puentedura EJ. Preoperative pain neuroscience education for lumbar radiculopathy: a multicenter randomized controlled trial with 1-year follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014 Aug 15;39(18):1449-57. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000444.

2. Morris S. et al. Function after spinal treatment, exercise, and rehabilitation: cost-effectiveness analysis based on a randomized controlled trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011 Oct 1;36(21):1807-14. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31821cba1f.

A native of San Diego for nearly 40 years, Nick Ng is an editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine, an online publication for manual therapists and the public who want to explore the science behind touch, pain, and exercise, and how to apply that in their hands-on practice or daily lives.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a B.A. in Graphic Communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014.

When he is not writing or reading, you would likely find him weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, or exploring new areas to walk and eat around Southern California.