Sciatica is often used rather loosely and refers to a particular set of symptoms rather than the specific underlying medical condition. It’s sometimes referred to as lumbar radiculopathy, and the symptoms can range from discomfort to severe pain that can be difficult to diagnose due to similar symptoms from other conditions, like the piriformis syndrome.

Getting treatment and identifying the cause of these pains can be a process of elimination. In this case, sciatica will be referred to as an irritation of the sciatic nerve not otherwise covered by another condition.

As a massage therapist, I empathize with my clients who complain of sciatica. Before I switched careers, I spent many years in the restaurant industry as a server, a bartender, a busser, and a prep cook. What those jobs all had in common were long hours, prolonged time on my feet, and hard, unforgiving floors.

By 2010, I had been in the industry for ten years, and even though I was only in my twenties, my body was really starting to feel it. My feet hurt from walking, my face hurt from smiling, and I started experiencing a strange pain when I finally stopped moving for the night.

When I got home at the end of a shift, I felt this shock of pain that ran from my backside, through the back of my leg, and into the sole of my foot. Sometimes it ached, sometimes it stabbed, but it was always only on my right side. Sometimes, it hurt so much I could not sit down or find a comfortable way to sleep.

I was young and I worked in an industry that did not prioritize “time off” or “healthcare.” I chalked it up to nothing more than nonspecific fatigue, overuse, and the physical toll of the job. I found out that this sharp, electrical sensation and its particular path was indicative of something more specific: sciatica.

I was far from alone. Sciatica symptoms have a lifetime occurrence in as little as 1.6% in the general population to 43% of the working population. They show no gender or age predominance among adults.

Sciatic nerve anatomy

The anatomy of the sciatic nerve and the surrounding structures give some insight into why this area can be fraught with sensory complications.

The location and sheer size of the sciatic nerve has earned it an infamous reputation. The largest nerve in the body, the sciatic nerve originates in your lumbar and sacral spine at the nerve roots of L4 to S3.

Part of the sacral plexus, which joins with the lumbar plexus to form the lumbosacral plexus, it runs through the gluteal region by way of an opening in your pelvis called the sciatic foramen.

It branches through your gluteal muscles and into the hip, and then descends through the leg muscle anatomy to enter the back of the thigh down through the back of the knee. Around this area (as each body is a bit different), it splits in two to become the tibial and common fibular nerves, which travel down to your lower legs.

Detailed image of the sciatic nerve.

The branches that extend into the hip supply the hip joint. The hip is a ball-in-socket joint with a variety of muscles around it for support and movement. The ball-in-socket shape allows the hip to move on its axis in many directions. In this variety of motion, the area also offers many scenarios where nerves can be pinched, irritated, or otherwise impinged.

The sciatic nerve has both motor and sensory functions. The motor qualities include bending your knee, bringing the thighs in toward your body’s midline, and pointing your foot and toes downward and upward.

The sensory aspects include innervation of the skin of the front, back, and outer aspect of your thigh and lower leg, as well as the skin of the top, outer side, and sole of your foot.

Movements, such as twisting, bending, and coughing, can cause sciatic pain to intensify. Pain can also be caused by flexion of the spine due to sitting and continual lifting and twisting.

A 2002 Finnish study linked jogging to a lower risk of incidental pain but a higher risk for ongoing symptoms. Conversely, physical exercise and sports activities didn’t seem to affect sciatic pain.

Sciatica symptoms

Symptoms that point to sciatica are:

- pain below the knee;

- leg pain that is worse than the back pain;

- a pain pattern that radiates towards the foot or toes;

- numbness that radiates down the leg into the foot;

- leg pain induced by the straight leg raise test;

- pain on one side at a time.

You may experience some collection of pain, burning, and numbness along the nerve route through your lower back, buttocks, the back of your leg, and into your foot. A shooting, sharp pain and “pins and needles” are common descriptors of sciatic pain. The affected nerve root determines where you experience these sensations.

Because sciatica is the irritation of the sciatic nerve, it can often be conflated with a variety of more specific conditions. In fact, sometimes the symptoms may not involve the sciatic nerve at all. Injuries and pathologies of the nearby structures like the gluteal tendons or the hip joint, can mimic sciatica symptoms.

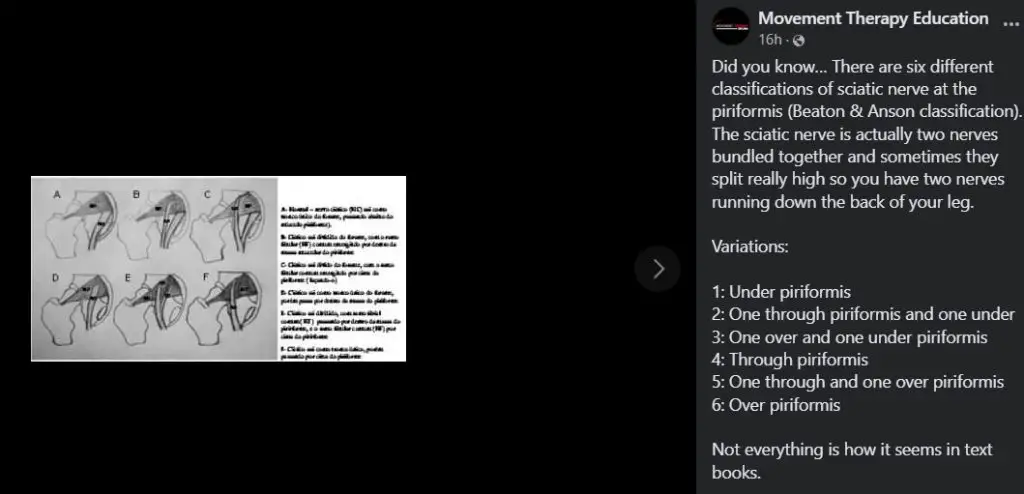

One common incidence is piriformis syndrome, where the piriformis muscle irritates the sciatic nerve and creates similar pain patterns. The sciatic nerve runs below the piriformis muscle, but there are several anatomical variations in which the arrangement is different.

The sciatic nerve could divide at this point and pass both through and below the muscle, through and above the muscle, or the entire sciatic nerve could pass above the piriformis. When the piriformis tightens or spasms, it can put pressure on and irritate the sciatic nerve, resulting in sciatica.

Movement Therapy Education recently highlighted such variations from a 2013 study.

Six variations of how the sciatic nerve and the piriformis muscle are positioned are identified in a 2013 Brazilian study.

Another nerve cluster response that may be mistaken for a sciatic complaint involves the cluneal nerves. The entrapment of the superior cluneal nerve near the iliac crest can be responsible for feeling pain in the low back and the leg. This is an example of a similar pain referral pattern that is unrelated to the sciatic nerve and can certainly be confused for sciatica.

Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) refers to the irritation caused by friction between the bones of the hip joint or pinching of tissue in the hip joint by the bones.

This friction or pinching can damage the cartilage of the joint, which may cause pain while sitting, low back pain, pain surrounding the sacroiliac (SI) joint, gluteal area or side of the hip, or a clicking sensation in the hip.

Hip osteoarthritis is a degenerative type of arthritis in which the cartilage in the joint gradually wears away. As one of the primary weight-bearing joints, the hip is a common place for osteoarthritis.

Since the sciatic nerve is so close to the hip joint, damage to the hip structures may be interpreted as sciatic pain. Disambiguating may involve identifying symptoms of stiffness, and groin pain or administering further medical imaging tests.

One case study even draws the connection between a herpes zoster (commonly known as shingles) outbreak and a misdiagnosis of sciatica! Without the characteristic skin lesions and with a burning nerve pain that are also endemic to shingles, an outbreak around the buttocks or thigh could mimic sciatica pain.

What causes sciatica to flare up?

Causes of sciatica include muscular spasms, disc herniation, spinal stenosis, and an overgrowth of bone on a vertebra. Mechanically, a combination of both inflammation and compression must be present for the nerve to display such symptoms.

A muscular spasm adjacent to the path of the sciatic nerve can put pressure on the nerve and cause irritation. This is quite common from muscles in the low back, glutes, or hip.

A herniated disc occurs when the soft filling between the bony spinal segments is damaged or displaced and, while not always correlated with pain, can cause sciatic pain if the disc compresses the nerve.

In the case of lumbar spinal stenosis, the spinal cavity that houses the spinal cord begins to narrow with age, leading to compression on the sciatic nerve and resulting in pain. If there’s an overgrowth of bone on a vertebra, or a “bone spur”, the bone can pinch or rub against the nerve and stimulate a pain response.

Lifestyle, demographic, and environmental factors can also heighten the risk for incidences of sciatica. A scoping review of the literature of common spinal disorders in 2018 found that higher incidences of sciatica are found in people who are overweight, smokers, and manual laborers.

Poor mental health, depression, age, and physical stressors specific to the spine, such as the vibrations of heavy machinery or vehicles, can also be predictive factors for sciatica. Those with multiple risk factors, such as obesity and lifting heavy objects, increased risk of more serious cases.

How long does sciatica last?

There is good news: sciatica can go away on its own.

Many cases resolve within six to eight weeks even without medical treatment or manual therapy. Once a medical professional has eliminated more serious causes, there are many self-care options that you can use to minimize pain and recurrence, such as heat or cold treatments, stretching, and finding a comfortable position when you sleep or sit.

If self-care solutions are not providing you relief, find help from a trusted medical provider who can help pinpoint the cause of your pain and introduce you to further treatment options.

While the onset of sciatica pain has more to do with exacerbating physical factors, maintaining healthy mental and physical habits make an impact on sciatica going away.

Does sciatica stretches, like the pigeon pose, help?

Stretching may help bring some pain relief, but the truth is, this might not work for everyone. Always consult with your medical provider before doing any of these stretches, especially if you have severe sciatic pain.

Pigeon pose

A popular stretch to relieve sciatic pain is a yoga pose called pigeon pose. Starting on all fours, bring one knee forward towards the same wrist. The opposite leg slides back with a pointed foot.

With one leg bent and brought forward and the other leg stretching back, it stretches the muscles in the buttocks, the anterior thigh, and surrounding the pelvis.

This can create a sensation of more space around an irritated sciatic nerve and bring relief.

Lean forward onto elbows or forehead to intensify the stretch. Using your arms for support allows more control over the stretch and weight.

Pigeon pose. Photo: Halley Moore

Figure four

The figure four stretches the glutes and the hip. You do this by lying on the floor or seated with one ankle crossed over the opposite knee and pulling them both back toward your body. An added comfort of this position is to rock your hips side to side to add a pleasant pressure on the back.

Should you massage a pinched nerve?

You probably shouldn’t massage a pinched nerve directly since it’s located pretty deep in the hips, which requires deep tissue work that may aggravate more pain and discomfort.

However, there are ways that massage therapy can offer sciatic pain relief, even if it’s just for the short term.

Ongoing pain can make everything feel more sensitive, so when you go see a massage therapist, the treatment shouldn’t cause you more pain.

A slow and gentle hands-on approach will give both you and the therapist a chance to explore what you’re feeling and to find some sensory input that brings you comfort and relief. Even the relaxation effect of a Swedish massage can be helpful when managing chronic pain.

For massage therapists, it’s important to be aware of red flags that can be associated with low back pain and leg pain. There are several spinal pathologies to think of when a client comes in with pain that seems like sciatica: cauda equina syndrome, a spinal fracture, spinal malignancy, or a spinal infection.

Cauda equina syndrome could include numbness in the lower limbs and sudden onset bladder or bowel dysfunction.

An older client with a history of trauma to the area, osteoporosis, or corticosteroid use could be a red flag for a spinal fracture. The combination of a history of cancer, low back pain, and unexplained weight loss might point to spinal malignancy.

Lastly, indicators of a spinal infection could be fever, chills, sweating and recent infection. If any of these conditions are suspected, it’s a good idea to have the client contact their doctor to eliminate these symptoms as a possibility for the pain.

If anything comes up as a red flag, it’s important to make them comfortable. Positioning can be a key in hands-on work. If the client is experiencing pain in a neutral position, any approaches attempted from that point will be an uphill battle. It’s difficult to see anything improve further if just lying on the table puts them under greater strain.

Lying flat may cause discomfort, so using bolsters and pillows to support the hips, knees, and legs can alleviate passive pain as you work with them. Other adjustments that may bring relief include lying supine with knees bent and feet flat, adding a pillow under the hips while prone to move them into slight flexion, or having them move into a side lying position with knees bent.

From the prone position, try supporting the leg of the affected side while bringing it over the sane side of the table. With a slight bend in the knee, gently pull the heel of their foot towards you while internally rotating the leg.

Alternatively, try pushing the heel of their foot away while externally rotating the leg. Check in periodically with the client to see how everything feels and if any adjustments need to be made. You may also monitor any hot spots of pain in the gluteal area for changes.

From side lying, start with knees bent and stacked, and then gently move the top knee up and over, letting it drape over the bottom knee. Apply gentle pressure to the low back, hip, and glutes while they are in this position. Creating a feeling of space in the low back area can also be helpful. This can utilize skin stretching, myofascial release, or any other slow stroke in any direction around the sacrum.

Whatever approach you try, let your clients’ experience guide your choices, and give their body time to adjust to any changes. Encourage them to be patient with their body, and consider taking your own advice.

With something like sciatica that can easily masquerade as other types of hip pain, diagnosis is complicated and is best left to a medical professional with a diagnostic scope. Encouraging a client to reach out to their doctor may give them more peace of mind and rule out any potentially dangerous causes.

In my case, I never sought out a medical diagnosis. I suppose I am a lucky example of someone for whom the pain resolved on its own. There could be a variety of contributing factors to pain, and “sciatica-like” symptoms don’t always add up to sciatica.

In fact, now that I know more about how my body responds to physical stressors and I’m armed with a little more anatomical knowledge, I suspect this may have been the work of a touchy piriformis.

Halley Moore, LMT

Halley E. Moore is a private practice licensed massage therapist, freelance writer, and small business consultant (Calliope Insights) in St. Louis, MO. Her diverse array of educational credits include a B.S. in Business, a massage therapy certification from The Healing Arts Center in St. Louis, various training in trauma-informed care, current enrollment in a web development coding course, and a dream of a private investigator’s license.

Halley first discovered an interest in anatomy by hanging upside-down from a trapeze as an aerial artist. Everyday after practice, new bits of her body hurt, so she figured it might be worth learning their names.