Living with chronic pain can leave you feeling overwhelmed and hopeless. Spinal cord stimulators are small implantable devices that are placed under your skin. They can help you manage pain and restore your quality of life and sleep by masking the pain signal before it can reach your brain. Spinal cord stimulators may also reduce the need for opioids and other pain medications.

These devices are often used together with other pain management strategies, including relaxation, exercise, and physical therapy. Spinal cord stimulators have been particularly helpful in managing the symptoms of chronic regional pain syndrome (CRPS), which can be quite debilitating.

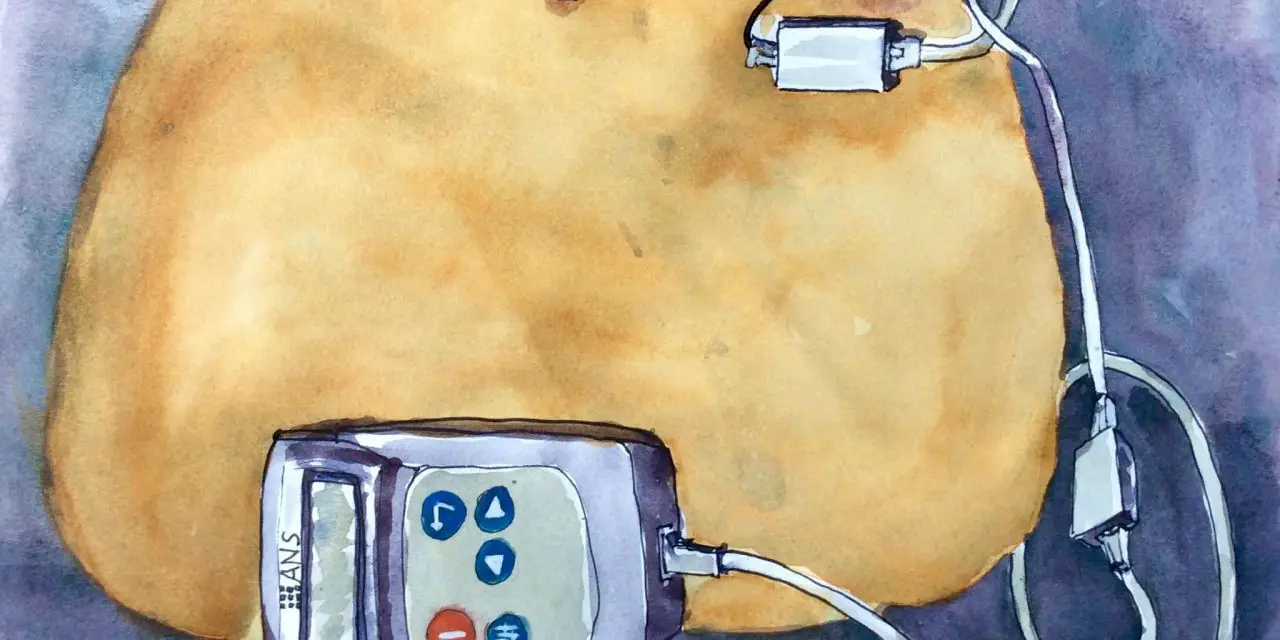

Kris Leong, who is an artist and CRPS advocate in Amsterdam, Netherlands, has a spinal cord stimulator to address the chronic pain associated with CRPS since 2014. For her, the device has been life changing.

“In general, my quality of life is far better with the spinal cord stimulator than it was without,” she said. “I still take medication, but less than it was before I had the spinal cord stimulator.”

What is spinal cord stimulation used for?

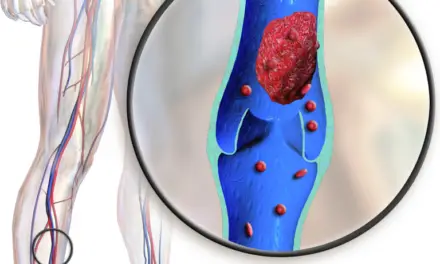

Spinal cord stimulators are used to treat many chronic pain conditions, such as chronic back or neck pain, arachnoiditis, post-surgical pain, angina, spinal cord injuries, nerve pain from diabetic or cancer-related neuropathy, peripheral vascular disease, post-amputation pain, CRPS (sometimes called reflex sympathetic dystrophy), and other painful conditions.

How does spinal cord stimulation work?

Once the spinal cord stimulator is implanted under your skin, it uses very thin wires to send electrical signals to your spinal cord. The wires carry the current from the device to the nerves of the spinal cord. When the device is on, the nerves are stimulated in the area where your pain is located which creates a “masking” of the pain.

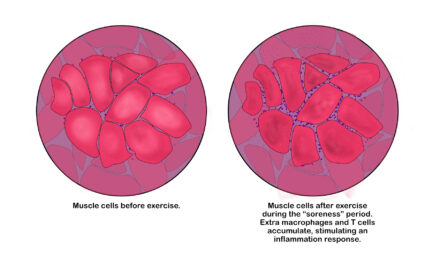

Imagine the pathways that carry messages from your body to your brain are like freeways. Different “freeways” sense different sensations (e.g. vibration, light touch, deep pressure, temperature, or pain). Luckily for us, the freeway that carries the stimulus for pain is always the slowest; so if you can send a stimulus on any of the other freeways to the brain, you can beat the painful stimulus to the destination (your brain!) and the new sensation will be felt.

In the real world, this is why we shake our hand when we hit our thumb with a hammer or why running something under cold water makes it feel better. It’s not that the pain stimulus is gone, but the pain freeway can’t get the message to your brain as fast as the others can—which is also why it still hurts when you stop shaking or take away the cold!

[Read more: Gate Control Theory of Pain for Manual Therapists and Patients]

What is the success rate of a spinal cord stimulator for CRPS?

According to a 2021 retrospective review, spinal cord stimulation is an effective treatment for CRPS. The review examined the medical records of 35 patients with CRPS who took part in spinal cord stimulator trials at two Finnish hospitals between 1998 and 2016. They determined its effectiveness by looking at trial success along with explantation rate, complications, and changes in medication use.

After a one-week trial, a permanent spinal cord stimulator was placed in 77% of patients. At the eight-year follow-up, 30% had been removed because it didn’t provide enough pain relief.

Revision was required more than 60% of the time and none of the patients using opioid or neuropathic medications were able to discontinue their use after two years. However, all that said, 70% of these patients were still using their device.

Pollard et al. performed a recent systematic review and meta-analysis that examined the effect of spinal cord stimulation on pain reduction. They found five trials that included nearly 500 patients with intractable spine and limb pain. When these patients used the spinal cord stimulator, the odds of reducing opioid use increased significantly.

Even when it is effective, spinal cord stimulation isn’t necessarily a quick fix. “For my legs, it was a world apart. I still had pain, and getting the settings right was a bit of an art but I was in no doubt that this really was the right thing for me,” Leong said. “I found the paraesthesia sensation worked not only to drown out the pain somewhat, but also helped me have better proprioception.”

She explains the process is rather arduous in that it doesn’t just involve a surgery or two; it’s a commitment to having frequent surgeries for as long as you have the device.

“I needed a replacement just short of two years later…there is little point in trying to save battery power and not using [spinal cord stimulation] to its best,” Leong said. “It had been an extraordinary two years; I had a lot of difficulties but also some wonderful breakthroughs.”

She explained that a lot of the difficulties weren’t related to the spinal cord stimulator or her chronic pain, but “the more difficult aspects were less stressful” because she wasn’t in as much pain.

“The wonderful times were even brighter because I had some so far. I was going out a lot, sketching with friends, and swimming again,” she said.

Who is a good candidate for spinal cord stimulator?

Dr. Ajay Antony, an interventional pain physician at The Orthopaedic Institute in Gainesville, Fla., who specializes in spinal cord stimulators, describes the devices as a “minimally invasive, testable, evidence-based option for [patients with] CRPS.”

The best candidates for spinal cord stimuation are those with neuropathic pain of the trunk and limb, which is most commonly seen in post-laminectomy syndrome and CRPS, he said. Those with widespread mechanical or bony pain are “not a good candidate.”

What are the risks of having spinal cord stimulation

With the good, comes some…not so good. Spinal cord stimulators can have a lot of complications. The overall incidence of complications varies from 30 to 40%. Problems can be classified as hardware-related, biological, or programming-related.

Leong emphasizes that the decision to get the device is incredibly personal because “it is a significant commitment,” which might not lead to the outcomes you want.

“It isn’t just one or two surgeries and it’s done but many surgeries for as long as you have one,” she said.

Hardware-related problems include lead failure/fracture, battery failure, or malfunction. At times, the lost paraesthesia coverage from lead failure (the most common hardware problem) can be adjusted with programming but this will often require a minor procedure to relocate the lead to its original position. Other hardware complications are relatively rare.

Infection, pain, and wound breakdown are the common biological complications. Some patients report pain at the site of the device or the leads once implanted. Also, the incidence of infection can be as high as 10% (more than double the highest rate for any surgery in the U.S.) and is often the cause for removal of the device. Less common biological complications that may be experienced are dural puncture or neurological injury.

One more complication (followed by some positives) noted by Leong is what happens after implantation. She recalls that the post-surgical restrictions were “really strict” and needed to be followed for a long time.

“MRIs are no longer possible and the magnetic components will set off metal detectors,” she said. “It wasn’t going to reduce my pain down to zero. It did turn the volume of my screaming pain down to a level that I could tolerate. It allowed me to make better use of my pool rehab. I was able to walk short distances with my stick or rollator. My mindset improved enough for me to try new social things.”

Programming-related complications may lead to a loss of sensation or painful/unpleasant paraesthesias. These are typically corrected by re-programming the device but may occasionally be classified as failure and the device explanted.

It’s notable that the success of these devices seems to be impacted by the experience of the implanter so when you are exploring options, the more experience the physician has in placing them, the better your chance of success.

As with any condition, it’s imperative that patients with CRPS work with their physician to thoroughly explore their options. Depending on your individual level of pain and dysfunction, the use of a spinal cord stimulator may be just what you need to restore your quality of life. Check with your physician to see if such procedure is the best option for you.

[Read more: Causalgia, RSD, CRPS: Does the Name Matter?]

Feature illustration courtesy of Kris Leong.

Penny Goldberg, DPT, ATC

Penny Goldberg, DPT, ATC earned her doctorate in Physical Therapy from the University of Saint Augustine and completed a credentialed sports residency at the University of Florida. She is a Board Certified Clinical Specialist in Sports Physical Therapy.

Penny holds a B.S. in Kinesiology and a M.A. in Physical Education from San Diego State University. She has served as an Athletic Trainer at USD, CSUN, and Butler University.

She has presented on Kinesiophobia and differential diagnosis in complicated cases. Penny has published on returning to sports after ACL reconstruction and fear of movement and re-injury.

Outside of the clinic, Penny enjoys traveling, good cooking with great wine, concerts, working out and playing with her dogs.