Connective tissues disease refers to the pathology of tissues that link your body’s organs, joints, and other structures in place. These connective tissues act like scaffolding, providing stability and allowing some degree of movement.

They’re composed of elastin and collagen, which are types of protein that you can find in skin, tendons, ligaments, bones, cartilage, and muscles. And in muscles, collagen makes up about 1% to 10% of their composition, which provides their form and stability.

Elastin acts like a rubber band that allows tissues to stretch and return to its unstretched state. You can experience elastin doing its job when you pinch your own cheeks or stretch your own ears.

But if you have a connective tissue disease, elastin and collagen are inflamed, which affects the proteins’ structures and functions. Depending on the type of disease, you may have super stretchy skin, hypermobile joints (“double-jointed”), reddish, rash-like skin, inflammation, or a combination of these and other types of symptoms.

While connective tissue diseases are relatively uncommon or rare, depending on the type, massage therapists and other manual therapists may likely work with such patients or clients during their career. Patients and clients may have joint and muscle pain and migraines that many athletes and other populations have.

This article summarizes what is known about connective tissue diseases and how research can help guide therapists to do their job.

If you are someone with a connective tissue disease, this can help you ask the right questions to your therapist if you are already seeing a massage therapist or another manual therapist.

What are the different types of connective tissue diseases?

There are two broad types of connective tissues diseases: mixed and undifferentiated. Some are hereditary, and others are autoimmune in nature. In some types, they have both characteristics.

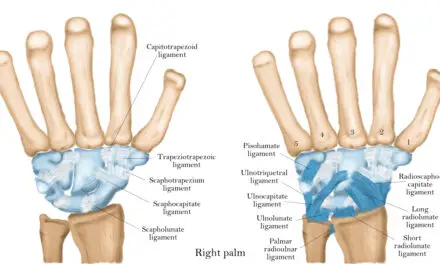

Mixed connective tissue diseases

Image: Nick Ng. Image credit: clockwise, upper left): Maria Sieglinda von Nudeldorf, BruceBlaus, Scientific Animations, CNX OpenStax ( CC BY-SA 4.0).

Mixed connective tissue diseases have two or more overlapping symptoms, which makes diagnosis and treatments difficult. These types include:

Scleroderma: a hereditary, autoimmune disease where your skin and various connective tissues harden, gradually replacing normal tissues.

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: genetic connective tissue disorder in which the skin is hyper-stretchy and the joints are hypermobile. Its symptoms can overlap with typical hyper joint mobility and rheumatic diseases.

Rheumatoid arthritis: an autoimmune, inflammatory disease where your immune cells attack healthy tissues, often in your joints.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): the most common form of lupus that spreads throughout your body, affecting different organs like skin, kidneys, joints, nerves, and blood vessels. Inflammation is one of the most common symptoms of SLE.

Sjogren’s syndrome: a systemic disease that spreads throughout your body where the notable symptoms are dry eyes and mouth.

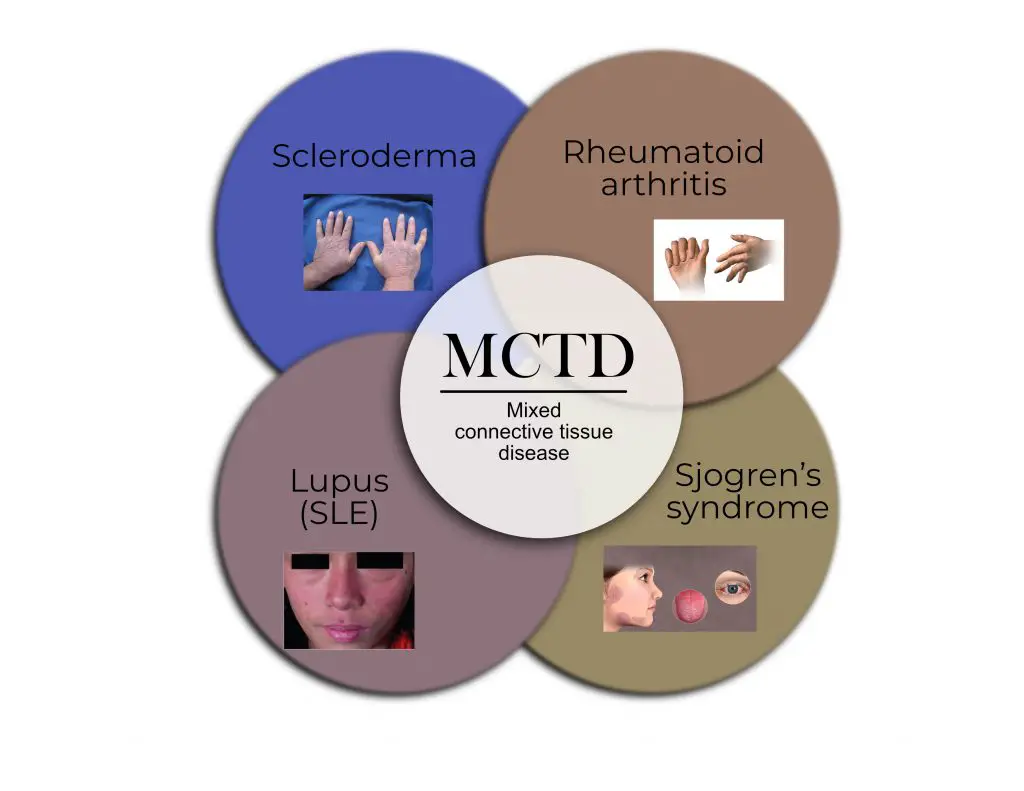

Undifferentiated connective tissue disease

Image: Nick Ng. Photo credit (clockwise, upper left): Nick Ng, Nick Ng, allinonemovie, Thomas Gavin (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Undifferentiated connective tissue diseases have the signs and symptoms of such disease, but they don’t have specific traits of any one disease which makes diagnosis and classification difficult. These signs include:

Myalgias: various types of muscle pain

Raynaud’s phenomenon: decreased blood flow to your fingers because of constriction of blood vessels due to cold temperatures. It’s not necessarily a precursor to Raynaud’s disease, but sometimes it may “evolve” into it.

Arthralgias: various types of joint pain.

Anti-nuclear antibody (ANA): a positive test for ANA means that your immune cells are attacking your body’s healthy cells. However, it’s difficult to determine the specific type of disease or disorder you have based on this test alone because of the overlapping symptoms.

In some people, their conditions may evolve into a specific type of connective tissue disease, which is kind of like a stem cell changing into a specific cell with specific functions.

For example, a patient with some of the symptoms of scleroderma but the disease doesn’t meet the criteria (yet) for clinicians to make a proper diagnosis. This condition is then called “undifferentiated,” a wait-and-see condition.

Connective tissue disease and COVID-19

People with connective tissue diseases are likely more susceptible to COVID-19 symptoms. Clinicians find it even more difficult to treat patients with a connective tissue disease who also have symptomatic COVID-19.

But children and teens with connective tissue diseases may have lower susceptibility to COVID-19 symptoms as long as they receive immunosuppressive therapy, according to a 2021 research from the German Rheumatism Research Center.

“The pause in therapy rather than the SARS-CoV-2 infection (especially as symptomatic) seems to be causative for the flare, particularly since the patient was not in remission before this treatment was stopped,” the researchers reported.

But given the small sample population of 76 patients with different types of connective tissue diseases, they suggested that future studies with larger case numbers are needed to confirm their findings.

What causes connective tissue diseases?

While scientists recognize that genetics and environmental factors (e.g. air pollution) can play a role in setting off the symptoms, no one really knows how someone would get a connective tissue disease.

What is known is that an antibody called U1-ribonucleoprotein (RNP) is present and responsible for most of the symptoms. This type of antibody is part of a huge family of RNPs that plays a role in protein synthesis in a cell.

Another type of antibody called anti-Smith (Sm) is commonly found among most patients with SLE, but it’s rarely found among those with kidney lupus and other rheumatic diseases.

However, a 2020 review found that such antibodies aren’t always reliable indicators of someone having a type of connective tissue disease.

From the four cohort studies the researchers reviewed — each with more than 100 subjects — many patients who have the antibody didn’t have a mixed connective tissue disease.

Likewise, there are those with these connective tissue disease symptoms yet have low levels or no anti-RNP antibodies, the researchers reported.

“The term UARD [undifferentiated autoimmune rheumatoid disease] is much prefered, with the need to explain to patients that half of them are likely to go and get more definitive diseases,” said Dr. David Isenberg, who is the coauthor of the 2020 review. “And which ones will do so is not, in my experience, predictable.

Although much is known about these antibodies and their roles, what triggers these antibodies to attack healthy connective tissues is still unknown.

What are the symptoms of connective tissue diseases?

Symptoms of connective tissue diseases vary yet many cases that fall under the mixed or undifferentiated categories have shared traits.

Dr. Patrick J.W. Vernables of the Kennedy Institute of Rheumatology at the University of Oxford wrote that mixed connective tissue diseases lack “any distinctive clinical features.”

He gave an example with Raynaud’s phenomenon, which is the decreased blood flow to the hands. It may be an underlying symptom of Raynaud’s disease, where there are spontaneous periods of vasospasms in the blood vessels.

This can be mistaken for a type of mixed connective tissue disease because swollen hands from edema and discoloration can be mistaken for other conditions, such as erythromelalgia and acrocyanosis.

How are connective tissue diseases diagnosed?

Clinicians typically use a blood serum biomarker test to diagnose whether you have a type of connective tissue disease or not. These biomarkers include anti-U1-RNP, ANA, and C-reactive protein.

Other tests include:

- Imaging (e.g. MRI, X-ray)

- Skin color checks (e.g. cheeks, hands, legs)

- Urine test

- Test for dry mouth and/or eyes (Sjogren’s syndrome)

However, these tests aren’t always reliable because there’s “no current evidence or agreement about the optimal criteria for diagnosis, follow-up or treatment strategies,” according to Alves and Isenberg.

Even if larger samples are used in future studies, there’s still no agreement to the diagnostic criteria since there are four different types with different test sensitivity and specificity.

“As clinicians we like to ‘fit patients into neat diagnostic boxes,’” Isenberg said. “But we need to accept that patients may [or] do develop conditions with some (but incomplete) features of well-established diseases like SLE, scleroderma. Time is the arbiter as to which patients do that. I routinely follow these patients up to five years. If nothing further has developed, I reassure them that there is a good chance that it won’t do so.”

How are connective tissue diseases treated?

Because there are no randomized-controlled trials yet to determine the “best” treatment for a specific type of connective tissue disease, management of the symptoms is the best treatment available. These include:

- Immunosuppressive medication (e.g. DMARDS)

- Electric heated gloves

- Prostaglandin infusion

- Systemic corticosteroid

- Exercise (e.g. strength conditioning)

- Stress management

None of these treatments should be approached with a one-size-fits-all mentality. Because there are so many variety of CTDs and each person has unique symptoms and reactions to treatments, check with your doctor for an appropriate treatment plan.

Note: This article DOES NOT substitute your doctor’s advice and expertise. This is for informational purposes only. If you suspect that you or someone you know and care about have a connective tissue disease, see your primary care physician for your personal advice and care.

What’s the prognosis (outlook) of connective tissue diseases?

Prognosis depends on several factors:

- Which organ(s) is affected

- Disease progression

- Degree of inflammation

- Treatment effectiveness

- Timing of treatment

In some cases, connective tissue diseases can be deadly, especially those that affect your heart or lungs.

A 2005 review by Swedish rheumatologist Ingrid Lundberg found that about 33% of patients who have mixed connective tissue disease have a benign (or asymptomatic) course but can turn symptomatic. Another 33% have an aggressive course, and 33% can manage the disease with immunosuppressants but still need such therapy for several years.

Lundberg also found that those who have pulmonary hypertension also have the highest mortality rate. More recent studies found similar results.

For example, in a 2013 Hungarian study of 228 patients with various connective tissue diseases, 22 of them died of pulmonary arterial hypertension, infection, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, and other heart conditions.

Isenberg said that the prognosis of most connective tissue diseases “differs little from SLE” — approximately 85% chance of survival over 15 years.

Living with connective tissue disease

If you’re worried about how well you’d live with connective tissue disease and deal with daily activities and chronic pain, you’re not alone. Many people with other types of pain, such as musculoskeletal pain and phantom limb pain, have similar experiences as you do.

While you cannot control your genetics and the progression of the disease, you can take control of how well you live by other means. These include regular exercise (any form that you like), having positive social support and engagement, and being able to continue to do the things you love and enjoy despite having a connective tissue disease.

A 2020 New Zealand study, led by Dr. Bronwyn Thompson from the University of Otago, examined a group of volunteers who have chronic pain from various connective tissue and related diseases, such as fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, and hypermobility from Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

They found that what matters to the volunteers the most is regaining their self-coherence, which is “a belief that personal capabilities, motivations, goals and ways of engaging in occupations make sense,” according to Thompson et al.

In other words, it’s about regaining their sense of self, which includes how they dress, get ready for work, doing house chores, and taking care of their children or a family member. So when chronic pain disrupts these daily activities and duties, these people’s sense of self-coherence is lost.

“Once a person is beginning to do what’s important and use coping strategies, then it’s time for them to begin future planning,” Thompson wrote. “This process [is] going to be relevant for the rest of the person’s life.”

She suggested that people in pain need to plan ahead in adapting different behavior changes, such as ways to express who they are.

“I think it’s an aspect of pain management that we rarely consider,” she wrote. “Having chronic pain can mean learning to grow, to keep developing, to become more resilient and allows us to develop different parts of ourselves. It’s more than just ‘returning to normal’ because, after all, what’s normal?”

A native of San Diego for nearly 40 years, Nick Ng is an editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine, an online publication for manual therapists and the public who want to explore the science behind touch, pain, and exercise, and how to apply that in their hands-on practice or daily lives.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a B.A. in Graphic Communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014.

When he is not writing or reading, you would likely find him weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, or exploring new areas to walk and eat around Southern California.