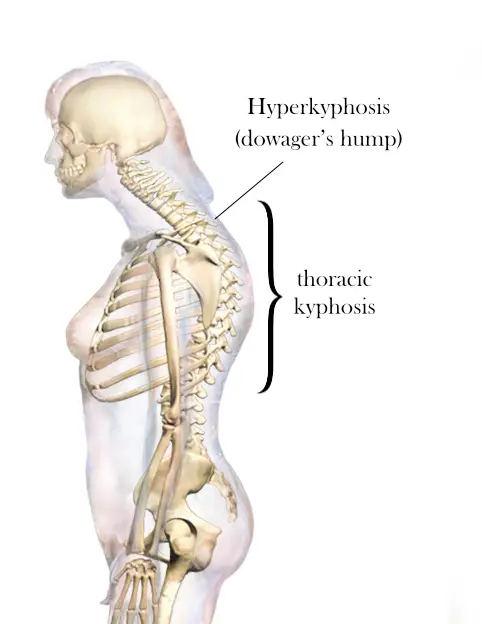

A dowager’s hump, which is a type of hyperkyphosis, often refers to the excessive curvature of the thoracic spine near the neck base. Most medical professionals agree that a “normal” range of the thoracic spine is between 20 to 40 degrees.

Any degree greater than 40 is classified as “hyperkyphosis” because some research has shown that such characteristic often correlates with less shoulder range of motion and/or having a type of vertebral disease.

Oftentimes that small bump at the top of the thoracic spine and a forward head mark the symptoms of a dowager’s hump.

While some people assume that having such a posture of any kind can cause back, neck, or shoulder pain, research in kyphosis finds a lack of a strong association between upper spine and neck posture with pain.

Even if pain and function aren’t an issue for some people with a dowager’s hump, they want to improve their posture for a “better” appearance.

And so, are there any dowager’s hump exercises that reduce the curvature or at least slow down the hunching progression? Let’s take a look at what science says.

Causes of dowager’s hump

You could get a dowager’s hump from various factors: lifestyle, injury, congenital factors, and environment.

Congenital kyphosis

There are two types of congenital kyphosis:

Type 1 is where the back arch of the vertebrae and spinal canal doesn’t form. This is where the spinal cord and cerebral fluid pass through.

Type 2 is where the front part of two vertebrae doesn’t separate during development during infancy or early childhood. This causes them two bones to fuse together as the person grows up, which likely weakens the upper spine support.

Aging

While aging is an inevitable factor that increases the risk of getting a dowager’s hump, research finds that this is only one causative factor among several.

A team of Iranian and American researchers reviewed 77 studies that examine the age-relating factors of hyperkyphosis. These include degenerative disc disease, genetic factors, injuries and accidents, and weakness in the back extensor muscles from muscle atrophy and/or weak electrical signals in the muscles and nerves. These are sign of “normal” aging.

Lifestyle

It’s possible that lifestyle may increase the risk of getting a dowager’s hump, however, no study has yet to establish this idea. However, some indirect evidence may provide some evidence.

A 2017 British study compared three groups of people’s weekly physical activity—almost no physical activity, moderately active, and highly active—and found that those who sit for more than seven hours a day have the least amount of thoracic spine mobility. They have more than 10 degrees less mobility than those who are active.

Lifestyle can shape how likely you’d get a dowager’s hump, but with regular physical activity, that can reduce the risk. (Photo by Andrea Piacquadio)

However, this study is done on young adults, which may not apply to middle-age and older cohorts.

Interestingly, a 2018 Spanish study of 118 women (ages 45 to 70) with fibromyalgia did not find sedentary lifestyle to be a factor in their adopted hyperkyphotic and forward head postures.

Perhaps the posture is an adaptive response to avoid pain.

Do exercises for dowager’s hump work?

Exercise may help with reducing the dowager’s hump or at least slow down or halt its progression. However, the scientific evidence is uncertain about how well it works.

Early reviews of the literature found some promising results. In 2014, a small team of American and Canadian scientists reviewed 13 qualified studies and found that eight of them reported improvements of the hyperkyphosis curvature.

A 2019 systematic review and meta-analysis of 10 randomized-controlled trials found that exercise has “a large, statistically significant, effect of exercise improving thoracic kyphosis angle” but not so much for lordosis.

The researchers reported that strengthening exercises are likely to be more effective than stretching alone, which should be done two to three times a week for eight to twelve weeks to see any significant improvements.

Despite the positive findings, researchers from Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia, reported these two systematic reviews had some flaws.

Dr. Hazel Jenkins, who led the 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis, and her colleagues mentioned that the 2014 review is based on older adults only, which might not apply to younger adults. The review also included non-randomized studies that may skew the results and outcome that favors exercise as an intervention for hyperkyphosis.

The 2019 review didn’t evaluate the quality and strength of the evidence, lumped all age groups together instead of evaluating each group separately, and didn’t report how long the treatments were done.

So Jenkins et al. decided to investigate by addressing these issues. Out of 21 qualified studies of exercise for hyperkyphosis, they found that structured exercise programs that last more than three months—and include other treatments like manual therapy and bracing— “did not show evidence of effectiveness in older adults.” The quality of these studies ranges from “low” to “moderate.”

While their results are “in alignment” with the 2019 review, Jenkins et al. reported that there’s a low number of studies that examined other types of conservative treatments, such as bracing. Other issues include small sample sizes, sampling bias, and questionable effect sizes in some of the included studies.

Their review still has limited evidence for younger adults with hyperkyphosis, but they suggested that “exercise should be considered as an initial treatment option.”

CAVEAT: Given the resilience and slow adaptability of connective tissues, three months or even a year of consistent exercise may be less likely to undo years or decades of behaviors and conditions that gets someone a dowager’s hump.

Habits of a lifetime count for something, but brief bouts for a couple of months can’t compete with years of practice. ~ Dr. Bronnie L. Thompson

Does a dowager’s hump brace work?

There’s little evidence that bracing would work for a dowager’s hump. Jenkin et al. found two qualified bracing studies that showed it has a “large effect” in reducing hyperkyphosis, but the evidence is weak because of their “imprecision” and publication bias.

Two additional studies were included in their meta-analysis, but there was “insufficient data” to calculate the effect size, which is important in determining how likely the results were based on chance.

Does chiropractic work for hyperkyphosis?

You may have seen before and after pictures of people getting their dowager’s hump improved after a chiropractor or physical therapist visit.

But these pictures are not reliable evidence to indicate that manual therapy adjustments are effective in changing the degree of posture over time because:

- We don’t know if the person had other types of treatments in addition to the manual therapy;

- We don’t know if the person simply changed their posture intentionally to exaggerate the differences for marketing purposes;

- We don’t know if the person is really a patient or an actor.

Jenkins et al. failed to find enough evidence to support the idea that chiropractic or any manual therapy adjustments can significantly reduce the dowager’s hump.

(I emailed Dr. Hazel Jenkins for further background about the literature and details about their findings, but they haven’t responded.)

So for now, exercise may be your best approach to reduce or at least slow down the gradual progression of the upper spine curve.

There’s no evidence (yet) that you need to do specific exercises, but with the guidance of a qualified physical therapist or another qualified healthcare professional, you will get the customized help to take care of your “bump.”

A native of San Diego for nearly 40 years, Nick Ng is an editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine, an online publication for manual therapists and the public who want to explore the science behind touch, pain, and exercise, and how to apply that in their hands-on practice or daily lives.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a B.A. in Graphic Communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014.

When he is not writing or reading, you would likely find him weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, or exploring new areas to walk and eat around Southern California.