The piriformis syndrome can be a bane for many athletes, particularly among those who perform endurance sports like marathoners, road cyclists, and rowers. Competitive distance runners keep a strict training schedule and are notorious for being able to rattle off their mileage for the day, week, and even year-to-date. Most have learned to create time in their busy running schedule for strength training, foam rolling, sleeping, and meal preparation.

If there’s one thing they cannot afford, it would be injury. So when a local competitive marathoner came to physical therapy with new onset back and buttock pain when he crossed his legs to tie his shoes, the race to get back on the road was on.

We ran (pun intended!) through all the necessary questions. He had not changed his shoes, running surface, mileage, or anything else related to running, but he had added a new element to his training: stair climbing at the local college football stadium.

In this case, the runner had a “typical’” tightness in his hips, but his tightness was usually bilateral and what he described as a “general achy” feeling. The new pain was only on his right side and was deep in his buttock region. He noticed that his pain worsened while he was sitting during his long commute to work. The tightness was relieved by a forward-fold stretch.

He also noticed a burning pain in the back of his right thigh and pointed to a particular spot near the center of his buttocks that was the most painful. It takes a keen clinician to know this was not low back pain at all; it seemed to be textbook piriformis syndrome.

Piriformis syndrome was first described by Yeoman nearly 100 years ago. W. Yeoman was a British physician and the president of the Royal Society of Medicine who wrote extensively on contemporary medicine in the early 1900s. The main features of the condition have long included: pain that worsens with bending or lifting and is relieved by traction; a palpable tube-like mass over the piriformis muscle; positive piriformis test; and pain with prolonged sitting.

Over time, a host of non-specific symptoms have been associated with piriformis syndrome, which make it a challenge for clinicians to diagnose. Some researchers have also challenged the findings and ideas of Yeoman about the nature of piriformis syndrome.

Since the dawn of this diagnosis, it has been hidden under the veil of other common low back related conditions. This is easy to believe considering the incidence of low back pain has long been high and is only getting higher.

Freburger et al. studied the increased prevalence in low back pain from 1992 to 2006 and found that more than 80 percent of adults will experience at least one episode of disabling low back pain during their lifetime.

Piriformis syndrome may be responsible for as many as six percent of all cases of low back pain and/or sciatica. About 40 million new cases of low back pain and sciatica are reported annually, which would be about 2.4 million cases of piriformis syndrome each year.

The onset of piriformis syndrome typically occurs in a person’s forties and fifties and affects women six times more often than men. It has been suggested that the wider pelvis found in most women may be a causative factor, however, the jury is still out on whether there’s a direct cause-and-effect relationship.

Piriformis syndrome can have many causes but the symptoms seem to be about the same. The patient with piriformis syndrome typically reports deep pain in the buttocks and shooting, burning, or tingling into the back of the leg. This pain doesn’t usually go lower than the knee.

Although the reports of pain location and quality are similar across patients, they can vary significantly with respect to intensity. A savvy clinician would be able to recognize the objective findings relative to piriformis syndrome, which allows patients to start treatment early and avoid long-term pain and dysfunction.

The inability to diagnose piriformis syndrome in a timely manner may lead to a domino effect of other conditions, such as chronic pain, paresthesias, and muscle weakness. Delaying a correct diagnosis is not only costly for patients, but also may involve expensive diagnostic imaging that nearly always turns up negative.

Time spent on ineffective or unnecessary therapeutic interventions can delay relief and the return to normal daily activities.

There are several conditions that can mimic piriformis syndrome. It’s important that trochanteric bursitis, sacroiliac joint dysfunction, disc injury, and facet joint arthropathy have been ruled out to ensure the chosen treatment is targeting the correct tissue.

How do you heal piriformis syndrome quickly?

The short answer is: you don’t. With any musculoskeletal condition, immediate improvement is often mistaken for recovery. It’s important to stay the course with stretching and strengthening even when things feel better right away. It takes about 12 weeks to build true strength, so improvements that come after a few weeks are not likely to last.

Because the piriformis and the muscles that work alongside it are integral to all lower body movements, it’s crucial to keep these muscles strong and pain-free so that you can perform your daily activities safely and effectively; otherwise, they become a literal pain in the butt!

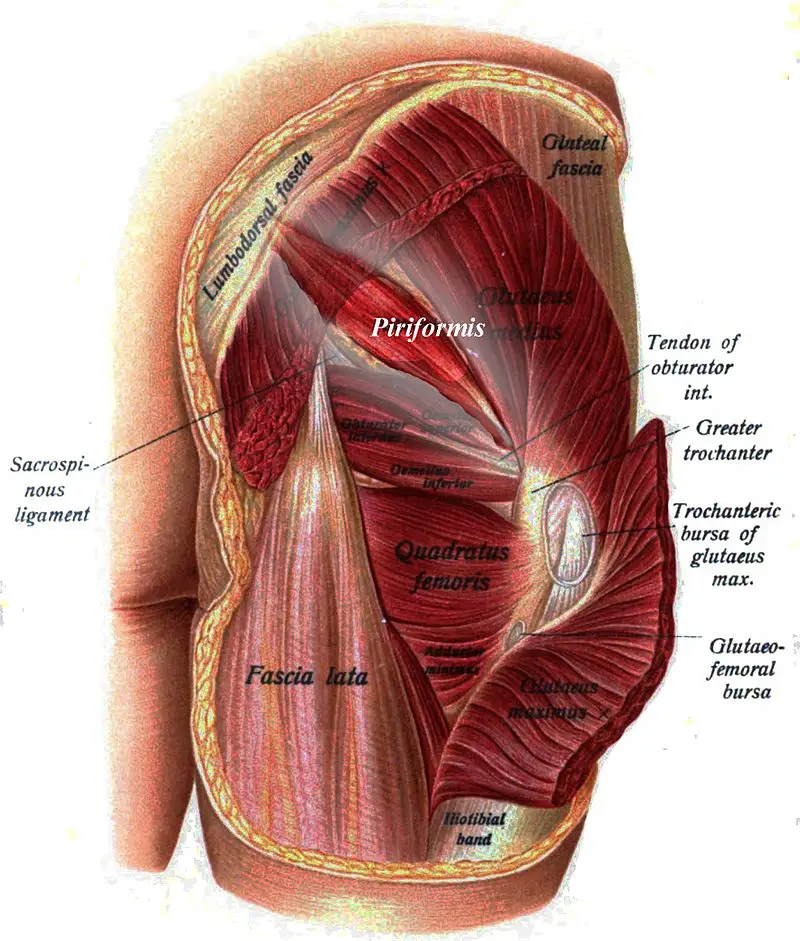

Anatomy of the piriformis muscle

A thorough understanding of the anatomical relationship between the piriformis muscle and the sciatic nerve is needed to recognize piriformis syndrome. The hip is a ball-and-socket joint where inherent stability is provided by the bony structure.

The hip joint not only relies on this bony stability but also on many large and small muscles to create movement and the endurance needed to support the body weight against gravity.

Image: Johannes Sobotta – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sobo_1909_295.png

Piriformis, latin for “pear-shaped,” is found deep to the gluteal muscles in the pelvic cavity. It’s the most superficial of the deep hip rotators. It starts on the lateral border of the sacrum and the sacrotuberous ligament and travels through the greater sciatic foramen (an opening formed by the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments) and the greater sciatic notch of the ilium. Then it attaches to the greater trochanter of the femur.

When the hip is extended, the piriformis is the primary external rotator, but when the hip is flexed, it acts as an abductor (muscles, or groups or muscles, that move a limb away from your body).

The piriformis is innervated by the L5, S1, and S2 nerve roots, which may provide at least some of the explanation for why pain in this area is often confused with disc-related pain. Lumbar disc pathology most commonly affects the L4 to L5 and L5 to S1 levels.

The sciatic nerve is well known as the largest peripheral nerve in the body. It’s made up of the nerve roots from L4 to S3 and divides into two major branches: the tibial nerve and the peroneal nerve.

The nerve fascicles of these two branches are separate but travel together in the upper (proximal) portion of the nerve; this means that nerve injury can preferentially affect one branch or the other.

For example, if the tibial portion of the nerve is injured, toe and foot weakness can be expected. If the peroneal portion of the nerve is damaged, there may be weakness in the hamstrings or along the muscles of the outside of the leg between the knee and ankle.

The peroneal branch is thought to be more often involved in piriformis syndrome because it’s less robust than the tibial nerve and runs laterally in the sciatic notch, making it more vulnerable to compression. The course of the sciatic nerve is such that if the piriformis muscle is inflamed or irritated, the nerve will be affected, and a sciatica-like pain will result.

Sciatic nerve anatomy variations

Not everyone has the same sciatic nerve anatomy! One Ethiopian study found that, among a sample of 28 cadavers (56 limbs total), about 11 percent of them had variations of the location of the sciatic nerve relative to the piriformis.

Another 14 percent showed sciatic nerve variation in relation to the popliteal region of the thigh. And among that group, three individuals had a third, unusual branch of the nerve at the back of the knee.

A study from Greece identified about six percent of 147 cadavers that had variations of the sciatic nerve and piriformis relationship.

Our anatomy is as unique as we are, and it’s important to use the patterns of signs and symptoms when diagnosing this type of problem and to use “normal” tissue healing timelines to determine if things are improving at the expected rate. If they aren’t, imaging may be needed to find the actual source of the pain.

Piriformis syndrome symptoms

The typical symptom of piriformis syndrome is pain that increases after sitting (e.g. cross-legged) for more than 15 to 20 minutes. Other signs may have a direct or indirect relationship with muscle spasm, nerve compression, or both.

Other common complaints are chronic, dull pain in the hip and gluteal area, pain when getting out of bed, difficulty with taking long walks or climbing stairs, pain in the back of the leg (thigh, calf, and/or, foot), and deep posterior hip pain that worsens with hip motion. Ninety percent of cases of piriformis syndrome are unilateral.

In the past, sciatica-like pain that comes along with piriformis syndrome has been thought of as a normal anatomical variant; the idea that a lot of structures live in a very small space and that the nerve may be pinched by other structures in that space has been embraced.

This is referred to as non-discogenic sciatic nerve entrapment. “Entrapment neuropathy” is the term used to describe compression of a nerve. In this case, the sciatic nerve may be impinged as the piriformis passes through the bony projections of the pelvis.

Signs and symptoms of such entrapment may include pain, tingling, skin sensitivity, numbness, and/or weakness. The quality of pain is often used to differentiate neuropathic pain from musculoskeletal pain, but terms like radiating, burning, or tingling should be taken with a grain of salt as these are non-specific and can be present in muscle pain.

Piriformis syndrome causes

Piriformis syndrome can be described as primary or secondary. Primary piriformis syndrome can be tied to an anatomical cause, such as split piriformis muscle, split sciatic nerve, or an uncommon sciatic nerve path. Causes of secondary piriformis syndrome may be macrotrauma, microtrauma, or local ischemia.

Less than 15 percent of cases are primary piriformis syndrome. In fact, the prevalence of secondary piriformis syndrome in people reporting low back pain has been reported in a wide range of 5 percent to 36 percent.

One cause of secondary piriformis syndrome can be macrotrauma, such as a fall onto the buttocks that leads to inflammation, muscle spasm or both, and microtrauma, such as too much running or direct and consistent compression.

It can also be the tightness or inflammation caused by damage to the muscle, which can decrease the blood flow in the area. In 90 percent of people, the sciatic nerve travels deep to the belly of piriformis, but if there’s an early division of the nerve into its tibial and peroneal branches, this may be a predisposing factor of developing piriformis syndrome.

The two most common potential mechanisms of compression are spasm and inflammation that cause hypertrophy and compression of the nerve between fascicles of the muscle belly. The anatomy of the piriformis is such that it becomes taut with just a few degrees of hip flexion, which creates compression and reproduces the sensations of sciatica any time a straight-leg raise is performed.

The blurred boundaries between what is piriformis syndrome and what is a secondary cause of sciatic neuropathy make it challenging to define a unique symptom cluster for piriformis syndrome.

Increased tone, tightness, and hypertrophy of piriformis, along with sacroiliac joint or piriformis muscle swelling, could all be contributing causes to the impingement of the sciatic nerve in the greater sciatic foramen. Imaging studies have shown hypertrophied piriformis in athletes across all sports, including runners and football quarterbacks alike.

Does piriformis syndrome ever go away?

Piriformis syndrome typically responds well to treatment that is made up of exercise, activity modification, medication, and occasionally, injection.

One study reported that 79 percent of patients with piriformis syndrome were at least 50% improved in self-reported pain and disability with non-surgical intervention. The condition may happen once or several times over the years; intensity and duration of symptoms don’t seem to change much with repeated episodes of pain and symptoms. Most people who experience the symptoms many times are able to self-manage with what they learned during their first stint in physical therapy.

Diagnosis of piriformis syndrome

The lack of a single, gold-standard test for identifying piriformis syndrome makes for a challenging diagnosis.

Once other neurological and musculoskeletal causes of pain are excluded, piriformis syndrome can be included. Other diagnoses to consider are lumbosacral radiculopathy, sacroiliac joint dysfunction, arthritis, disc pathology, or hip pathology.

On examination, “piriformis sign” will be present. Piriformis tightness will create external rotation of the hip that can be seen by looking for a toe-out position.

Other clinical findings may include buttock pain, pain with lengthening of the muscles, tenderness around the sciatic notch, and positive special tests. The FAIR test is most commonly used for piriformis.The test is positive if there is pain or limitation in the movement.

The Freiberg Maneuver (forceful internal rotation of the hip in supine with knee extended) is positive if the patient feels pain.

The Pace Maneuver begins with the patient seated with their legs dangling over the side of an examination table. The examiner resists hip abduction at the knees, and the test is positive if the patient shows weakness, uncoordinated movement (shaking or juddering), and/or pain.

The Beatty Maneuver is performed in a side-lying position on the unaffected side with the knees slightly bent. The patient actively abducts the affected side several inches. The test is considered positive for piriformis syndrome if pain is reproduced in the deep gluteal region but can also be indicative of lumbar disc disease if low back pain is present.

What Is Femoroacetabular Impingement? Symptoms of gluteal tendinopathy may overlap with FAI.

Piriformis syndrome treatments

Piriformis syndrome can be treated both with medications and non-drug options. Anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and muscle relaxer medications have all been used successfully in the treatment of the syndrome. Conservative management centers on physical and massage therapy that includes stretching, strengthening, and a gradual return to functional activities.

Patients who fail conservative management may find relief from steroid injections, Botox, or even surgery. As with most conditions, surgery should be a last chance option, not a first line intervention.

Pain-killing injections

Injections can be anti-inflammatory medications or paralytics (medicines that purposely cause paralysis). In either case, a single injection may not be enough to generate lasting pain relief.

Fifty patients with hip and/or leg pain with a positive FAIR test or pain in the piriformis muscle participated in a study on the effectiveness of local anesthetics and corticosteroid injections.

The patients were randomly assigned to two groups: the first group was injected with lidocaine only (local anesthetic) while the other group had lidocaine plus betamethasone (local anesthetic plus corticosteroid).

The researchers found pain was reduced when patients were at rest, in motion, at night, and with long-duration sitting, standing, or lying in both groups. This suggests local anesthetics may be all that’s necessary to find relief in these patients.

Stretching

Stretching the piriformis muscle to relieve sciatic nerve compression is a mainstay of conversative treatment. The most effective stretching position is similar to the FAIR test where the patient lies supine and then moves into hip flexion, adduction, and internal rotation.

Supine piriformis stretch. Photo: Penny Goldberg.

Pressure can be applied through a downward force at the knee from the patient’s hand on the same side, an external rotation force at the distal tibia from the patient’s opposite hand, or both.

Stretching can also be performed in a seated position with the affected leg crossed over the unaffected leg in a figure-4 position; the patient can either pull their ipsilateral knee to their contralateral shoulder or hinge forward at the hips to intensify the stretch. Stretching of piriformis should be followed by strengthening of the hip abductors and external rotators.

Seated piriformis stretch, knee to shoulder. Photo: Penny Goldberg.

A prospective study of 250 patients (with an additional 30 controls) with piriformis syndrome found that it took an average of seven weeks of analgesics, muscle relaxers, and physical therapy that included massage for half of the patients to reach full recovery. The program included stretching for the hip flexors, quadriceps, hamstrings, adductors, and piriformis.

Physical therapy also included contract-relax stretching of the piriformis, Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS), abdominal strengthening, and McKenzie-based flexibility exercises.

The combination of medication and rehab treatment was successful in about 51 percent of the patients. Those who did not find relief with the initial program were given Botox injections.

Fifteen of 19 patients that were unresponsive to conservative treatment methods underwent surgery with ‘good’ or ‘very good’ results. It’s clear from these results that conservative rehabilitation has a major role in treating piriformis syndrome.

Surgical management of piriformis syndrome may create nerve decompression through release of the tight muscles or removal of adhesions and scar tissue from the nerve. As in any procedure, surgery is never a guarantee of symptom resolution, and as such, it should only be considered as a last resort.

Readers are advised to consult with a physician or other qualified medical professional to determine which course of treatment is best for them.

Piriformis syndrome exercises: which ones work?

Electromyography (EMG) is commonly used to assess the activity levels in pre-identified muscles during specific exercises. Muscle activation is measured by using electrical activity levels with the assumption that exercises that produce higher levels of activation in a muscle, are better choices for strengthening that specific muscle.

A systematic review of the EMG activity of dynamic hip abduction and external rotation exercises found that standing exercises produced more muscle activity than the side-lying ones.

In the review, seated machine exercises produced the most overall activity but because there was only one study that used this mode of exercise, comparison to the activity levels produced in the other two positions is limited.

The review found that EMG activity was either high or very high in the following exercises:

Lateral step-ups

Photo: Penny Goldberg

Side bridges with abduction

Side bridge with abduction. Photo: Penny Goldberg

Standing hip abduction with ankle resistance

Hip abduction with resistance. Photo: Penny Goldberg

A study from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill looked at gluteal muscle activation during common rehab exercises and found that EMG activity was highest in side-lying hip abductions, single-leg squats, lateral band walks, and single-leg deadlifts.

The goal of physical therapy for piriformis syndrome is to have decreased symptoms, full range of motion, and improved strength and endurance for functional activities.

How to sleep with piriformis syndrome

Finding a sleeping position while battling piriformis syndrome does not have a “one-size-fits-all” approach. Much like everything else we do, sleep positions should be performed within moderation. There’s no single position that is “right” for sleeping, but research suggests that if we can avoid stomach sleeping, we should follow the evidence. Our bodies like variety, and so, the secret to the best sleeping position for piriformis syndrome may be in alternating between lying supine and side-lying on either side.

Some people with piriformis syndrome often face the difficulty of creating a regular sleep schedule. In what is likely the most well-known study on intradiscal pressure, Nachemson established that pressures in the lower back are lowest in the supine and side-lying positions.

These positions are desirable for low back pain because when disc pressures are low, nerves are not being compressed and relief is found. In piriformis syndrome, these are also positions of relief, perhaps, because of the low intradiscal pressures or they allow the piriformis to remain in a neutral position.

Piriformis massage

Massage therapy may alleviate the symptoms of piriformis syndrome. It’s important that the massage therapist maintains excellent communication with the patient while working in this area and that appropriate draping is utilized. Treatment should start with the most superficial muscle: the gluteus maximus. This muscle is the link between the low back, hip, and pelvis so starting here will improve overall motion in the area.

Photo: Penny Goldberg

This region is somewhat tender on most people, which makes it susceptible to reflexive tightening when touched. Starting with an open palm to create a broad contact surface can help your patient remain comfortable and relaxed. Once the tightness has been reduced, you can start to work toward the underlying piriformis muscle.

The piriformis is quite deep, and thus, getting to it with manual therapy can be very uncomfortable. Again, taking measures to reduce reactive muscle tightening are of utmost importance. One way to do this is with an active engagement lengthening technique.

To do this, start with the patient lying prone. Passively flex the patient’s knee on the involved side and place the hip in full external rotation.

Photo: Penny Goldberg

First, ask the patient to hold as you gently pull their lower leg toward you. Then tell them to slowly release the contraction as you continue to move their leg into internal rotation. As this movement occurs, apply a slow stripping technique directly over piriformis, moving forward along the muscle three to four inches with each movement.

Photo: Penny Goldberg

This can be repeated several times until the entire length of the muscle has been addressed. This technique should be followed by stretching and strengthening to enhance neuromuscular control of the recently restored hip motion.

To address the hip abductors with massage, start at the lateral pelvis with broad contact strokes. These strokes should address the entire length of gluteus medius and minimus from the iliac crest to the greater trochanter of the femur. Following the initial relaxation, specific deep techniques can begin.

Photo: Penny Goldberg

Tissue damage at the musculotendinous junction or tendinosis are common in those with chronic hip pain. Deep friction massage in the tendons region may encourage healing by increasing blood flow to the area. This new blood carries oxygen and other nutrients that contribute to the healing environment.

Also, active engagement techniques may also be used to address hip abductor tightness and restrictions. To do this, the patient should be lying with the affected side up.

Photo: Penny Goldberg

Ask the patient to actively move into adduction as far they are able, even if this is below the level of the table. As they move into maximal adduction, the massage therapist can perform a deep-stripping technique over the hip abductor group.

This may be painful and the massage therapist should move slowly and carefully so that the patient has enough time to provide feedback on tolerance.

We have learned a lot about the diagnosis and treatment of piriformis syndrome in the last 100 years, and there are definitely some overlaps of symptoms among different types of hip pain.

What is clear from decades of work is that if we listen to the patient’s story and do a thorough clinical examination, we can confidently make this diagnosis and start delivering the correct treatment so that the patient can return to activity quickly, safely, and without recurrence.

Penny Goldberg, DPT, ATC

Penny Goldberg, DPT, ATC earned her doctorate in Physical Therapy from the University of Saint Augustine and completed a credentialed sports residency at the University of Florida. She is a Board Certified Clinical Specialist in Sports Physical Therapy.

Penny holds a B.S. in Kinesiology and a M.A. in Physical Education from San Diego State University. She has served as an Athletic Trainer at USD, CSUN, and Butler University.

She has presented on Kinesiophobia and differential diagnosis in complicated cases. Penny has published on returning to sports after ACL reconstruction and fear of movement and re-injury.

Outside of the clinic, Penny enjoys traveling, good cooking with great wine, concerts, working out and playing with her dogs.