The FITT principle is a framework used to design exercise programs, which was developed by the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) in 1975. The acronym stands for Frequency, Intensity, Time, and Type and is used to prescribe and adjust exercise variables.

Since then, the guideline is updated every four to six years, with the latest update that included volume and progression—hence the FITT-VP principle. Here’s how you use it:

Frequency: How often you exercise a week. The ACSM recommends that you do moderate-intensity aerobic exercise for at least 150 minutes per week or high-intensity aerobic exercise for at least 75 minutes per week.

Break it down to 3, 4, or 5 days per week, whatever fits your schedule. If you can’t do one 30-minute session, spread it out to two times a day in two 15-minute bouts.

Strength training exercises should be done at least two days per week, targeting all major muscle groups. Depending on the exercise intensity and the type of workout you do, give yourself one or two days of rest between strength training sessions.

Intensity: The level of effort you exert during exercise. It can be measured using heart rate, perceived exertion, or the “talk test.” For aerobic exercise, you should be doing between 50%–60% of your maximum heart rate (MHR) if you’re a beginner or haven’t done it in a long time. If you’re experienced, aim for a higher MHR, such as 70%–90%.

Of course, the intensity can vary among each person. Even a 50% MHR workout can be quite intense for someone with a heart or breathing condition. So check with your doctor or an experienced and qualified fitness professional to help you set the right range for you.

Strength training intensity can be adjusted by changing the amount of weight or resistance used or the type of strength exercise (e.g. chest press machine vs. dumbbell chest press, traditional weight lifting vs. functional strength training)

Time: The duration of an exercise session. For aerobic activities, aim for a range between 10–30 minutes.

For strength training, perform 2–3 sets of 8–12 repetitions for each exercise.

[Details on sets and reps, tempo, and rest periods.]

Type: The kind of exercise you like to do. This can be walking, running, cycling, swimming, weightlifting, yoga, or martial arts. Choose activities that align with your personal preferences, goals, accessibility, and abilities.

Volume: The total of work and time you did during a week. For example, if you jog for 30 minutes a day, 4 days a week, and perform strength training three times a week for 30 minutes a session, then your total volume in minutes would be 210 minutes a week—or 3.5 hours of exercise a week.

Progression: You can use different variables to gauge how much progress you have made since you started to exercise. These can be weight, duration, number of reps, and perceived exertion.

(Image via Midjourney by Nick Ng)

The FITT principle may not be that important; behavior is key

Despite the benefits and updated FITT-VP principle, they aren’t enough to provide exercise adherence, according to some exercise researchers. What is missing, they argue, is the “fun” factor.

In 2009, the researchers from the University of Victoria in British Columbia—led by Dr. Ryan E. Rhodes—reviewed 27 qualified trials and found that frequency, intensity, time and type variables “showed null effects” on exercise behavior. In other words, they do not influence (much) on someone’s ability to stick to their workout.

They argued that behavioral factors are more important, such as personality, social cognitive, environmental, and socioeconomics, are more likely to influence exercise adherence since they “have amassed considerable evidence as correlates or determinants of physical activity.”

In 2022, Rhodes and two other researchers published a systematic review that examined 77 potential behavioral factors that influence people to exercise and be more active. This is based on the intention-behavior gap theory that tries to explain what motivates people to do certain things, like exercise, and what prevents them from doing so—even if they have a strong intent.

After reviewing 129 trials, they found:

Demographics

- People who are employed are more likely to exercise than the unemployed.

- Age and education level have mixed effects.

- Gender, income, body mass index, and marital status have almost no effect.

Behavior

- People who are more conscientiousness are more likely to follow exercise guidelines.

- But extraversion has mixed results.

- Reflective and reflexive motivation have higher influences than other types of behaviors.

Environmental

- Accessibility, safety, aesthetics, and infrastructure quality have little to no effect on exercise motivation.

“The current physical activity recommendations in terms of frequency, intensity and duration offer a wide range of alternatives for the population,” Rhodes et al. wrote. “This is a positive because it offers great freedom of choice in which health promoters can then tailor to meet their client’s desired needs without extended consideration of how these characteristics may affect adherence.”

However, they cautioned that the guidelines from the ACSM and Health Canada can be difficult to interpret and follow because they can be adapted in so many different ways.

In 2018, researchers from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill expanded Rhode et al.’s 2009 review and included eight additional trials to the 27 trials. They found one thing in common when revised the evidence: “programs that include a behavioral model generally attained greater adherence,” they wrote.

“The physiologically-based FITT principle recommendations are not useful if an individual’s lack of exercise enjoyment prevents them from adherence,” they wrote. “Although there are differing guidelines for FITT among these populations, all populations would likely better adhere to exercise if enjoyment was prioritized.”

The team isn’t saying that the original four factors aren’t important; it’s just that they don’t “encompass key factors” in determining whether someone will continue to regularly exercise or not.

They emphasize that the hedonic theory should be considered, which includes the clients’ experience and relationship with exercise and how they feel mentally during and after exercise. This can help fitness and healthcare professionals decide the best approaches to help them stick to an active lifestyle.

“At the time, the [ACSM] clearly defined recommendation guidelines for prescribing exercise, which are characterized by the FITT principle, despite Dr. Rhodes’ 2009 systematic review suggesting the manipulation of FITT did not seem to have a great effect on adherence,” said Kathryn Burnet, who is one of the researchers of the 2018 review. “We recognize that attention to ‘fun’ does add an extra layer of complexity to exercise prescription, therefore, we suggested using simple tools to measure enjoyment may better inform exercise prescription.

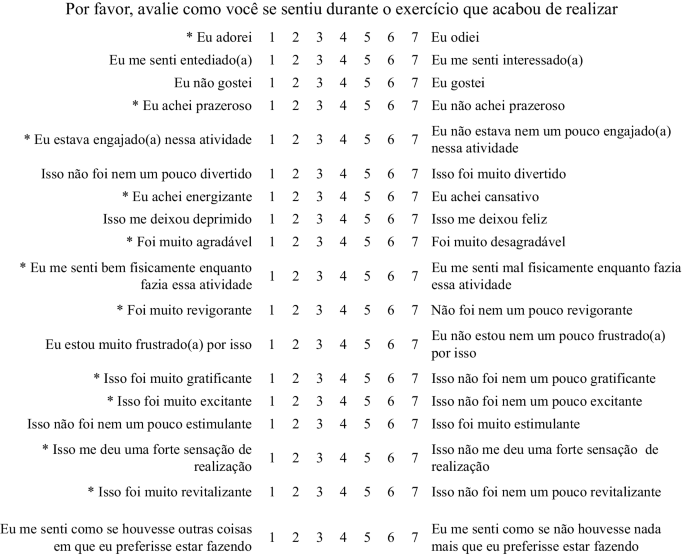

And this fun measurement tool is called the Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale (PACES), which was developed in 1991 by two psychologists Diane Kedzierski and Kenneth J. DeCarlo. It has 18 questions that ask and measure how enjoyable exercise is for patients (e.g. “I enjoy it; I hate it,” “it’s no fun at all; it’s a lot of fun”) Since then, it’s been modified many times to adapt to certain populations in different countries.

PACES in Portuguese. Source.

So keep in mind that exercise isn’t just about the physiological benefits. The psychological and social benefits that exercise provide are also part of the picture.

“I move because I love the feeling of my body in rhythm with the music, the wrench of those weeds as they get ripped from my garden, the stretch of my stride as I walk across the park, the ridiculousness of my dog hurtling after a ball,” wrote Dr. Bronnie Thompson, who is an occupational therapist and teaches at the University of Otago in New Zealand. “Exercise might be ‘corrective,’ to increase cardiovascular fitness, because it’s part of someone’s self-concept, to gain confidence for everyday activities, to beat a record or as part of being a good role model. Whatever the reason, tapping into that is more important than the form of the exercise.”

“I move because I love the feeling of my body in rhythm with the music, the wrench of those weeds as they get ripped from my garden…whatever the reason, tapping into that is more important than the form of the exercise.”~ Dr. Bronnie Thompson. (Images by Nick Ng via Midjourney)

A native of San Diego for nearly 40 years, Nick Ng is an editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine, an online publication for manual therapists and the public who want to explore the science behind touch, pain, and exercise, and how to apply that in their hands-on practice or daily lives.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a B.A. in Graphic Communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014.

When he is not writing or reading, you would likely find him weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, or exploring new areas to walk and eat around Southern California.